Piro Preman | |

|---|---|

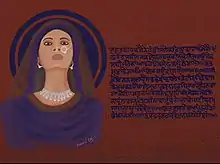

Artist's Representation of Piro Preman featuring verses from her poetry - Ik Sau Saat Kaafiyan | |

| Born | 1832 |

| Died | 1872 (aged 39–40) |

| Resting place | Chathian Wala, Kasur District, Punjab, Pakistan |

| Notable work | Ik Sau Sath Kafian |

Piro Preman (1832–1872) was the first female Punjabi poet, and an ex-Muslim follower of the Gulabdasia sect.[1][2][3][4] She was formerly a Dalit Mirasi Muslim courtesan named Ayesha.[5][6][7]

Biography

Little is known about Piro's life.[8] She apparently had Dalit origins.[9] Her mother is said to have died early after she was born and she accompanied her fakir father to various places of pilgrimage.[8] During one of these trips, she is believed to have been taken by a Lahori man who sold her into prostitution.[8] She is believed to have been sold into prostitution at Heera Mandi, the red-light district of Lahore.[8] She escaped Heera Mandi and went on to become a devotee of Gulab Das at the Gulabdasi Dera in Chathian Wala (in present-day Pakistan).[8] Das was a Sikh Jat who founded the Gulabdasi sect. The sect was based on Hindu–Sikh asceticism, but considered themselves to be neither Hindu nor Sikh.[10][11]

Most of the information about Piro comes from her own autobiographical verses, the Ik Sau Sath Kafian or the "One Hundred and Sixty Kafis (160 Kafis)", written in the mid-nineteenth century. In 160 Kafis, Piro describes a series of events in her life after she began living with Gulab Das in Chathian Wala. Piro refers to herself as a prostitute, and also a Muslim. Following her arrival in Chathian Wala, Piro writes that her "professional wardens" from Heera Mandi followed her and persuaded Gulab Das to send her back to Lahore. She ultimately agreed to return to Lahore, where she describes a confrontation with mullahs and qazis who assume that she has not only become an apostate, but also converted to the religion of her guru, thus becoming a kafir. Piro does not deny apostasy or conversion, but refuses to convert back to Islam. She abuses the mullahs and Islam, and praises the spirituality of her guru. According to historian Anshu Malhotra, "The unabashed use of language that might be considered vulgar among the respectable today, adds a colourful dimension to Piro’s speech."[10]

"Making false religions and promises,

You make Turks by snipping the penis and the moustache;

Hindus are made with janeyu and chat,

Women cannot be made thus, they are both wrong."

— Piro Preman, translated by Anshu Malhotra[12]

Piro writes that her actions result in her being abducted, and forcibly transported from Lahore to Wazirabad. She is incarcerated at Wazirabad by a woman named Mehrunissa. Piro describes that she was able to befriend two women, Janu and Rehmati, and utilize their help to send a message to Gulab Das. The guru sends two of his disciples, Gulab Singh and Chatar Singh, to Wazirabad. With the help of sympathizers, the disciples are able to rescue Piro and bring her back to Gulab Das' establishment in Chathian Wala.[10]

Piro and Gulab Das shared an intimate relationship despite social and religious pressures.[13] The two were interred together at a tomb in Chathian Wala.[14] Although the Gulabdasis were neither Hindu nor Sikh, following the Partition of India, they were expelled from Chathian Wala by the now Muslim-majority populace in Pakistan. The sect subsequently fled to India where they settled in Haryana.[15]

In popular culture

Piro's life has been the subject of two Indian plays - Piro Preman by Shahryar, and Shairi by Sawrajbir. Shairi was also performed by Pakistani theatre group Ajoka Theatre led by Madeeha Gauhar in Lahore and Amritsar.[11]

References

- ↑ "Piro Preman".

- ↑ Malhotra, Anshu. "Telling her tale? Unravelling a life in conflict in Peero’s Ik Sau Saṭh Kāfiaṅ. (one hundred and sixty kafis)." Indian Economic & Social History Review 46.4 (2009): 541–578.

- ↑ Singh, Neeti. “Peero: Maverick Bhakta and First Woman Poet of Punjab.” Indian Literature, vol. 62, no. 4 (306), 2018, pp. 201–13. JSTOR, JSTOR 26792168. Accessed 24 Jan. 2023.

- ↑ "Chapter 7: Panths and Piety in the Nineteenth Century: The Gulabdasis of Punjab". Punjab Reconsidered: History, Culture, and Practice. Anshu Malhotra, Farina Mir. New Delhi, India: Oxford Academic. 20 September 2012. pp. 189–220. ISBN 978-0-19-807801-2. OCLC 768071511.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Dutt, Nirupama (1 April 2010). "Waiting for spring - The emergence of a Dalit identity in Punjab is a recent development, spurred in part by the failure of Sikhism to abandon caste discrimination". Himal Southasian. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

The second known Dalit writer of Punjab was Peero Preman (1830-1872). Peero had earlier been a Muslim courtesan named Ayesha, and later joined the Gulabdasia sect and inherited sainthood from her mentor, Gulab Das.

- ↑ Kazmi, Sara (February 2022). Writing Resistance in the Three Punjabs - Critical Engagements with Literary Tradition (PDF). Faculty of English, Queens’ College, University of Cambridge. p. 96.

Peero was a Muslim woman in eighteenth century Punjab who disavowed her religion and joined the Gulabdasis, an unorthodox sect that drew on the ideas of Bhakti and Sufi devotion to criticise organised religion and caste inequalities.

- ↑ Malhotra, Anshu (2017). Biblio: review of books - Deras, disciples and doubleness - Piro and the Gulabdasis: Gender, Sect and Society in Punjab. Vol. XXIII. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-19-946818-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Khalid, Haroon (3 January 2018). "Piro Preman, the Punjabi poet who pushed the boundaries of sexuality with her verses". Dawn.

- ↑ Singh, Perneet (25 January 2010). "Jaipur Literature Festival: Spotlight on Punjabi Dalit writing on final day". The Tribune.

- 1 2 3 Malhotra, Anshu. "Theatre of the Past: Re-presenting the past in different genres" (PDF). Nehru Memorial Museum and Library. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- 1 2 Malhotra, Anshu (6 December 2012). "The importance of being Piro in Punjab". The Tribune. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ↑ Khalid, Haroon (3 January 2018). "Piro Preman, the Punjabi poet who pushed the boundaries of sexuality with her verses". Dawn.

- ↑ Awan, Mahmood (25 January 2015). "The feminine metaphor". The News on Sunday. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ↑ Khalid, Haroon. "Together forever". The Friday Times. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ↑ Khalid, Haroon. "The last stand". The Friday Times. Retrieved 19 December 2016.