.jpg.webp)

Plasticrusts are a new type of plastic pollution in the form of plastic debris, covering rocks in intertidal shorelines which vary in thickness and in color and are composed of polyethylene based on fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis.[1][2] They were first discovered on the South coast of the volcanic island of Madeira in the Atlantic Ocean in 2016 and have additionally been found on Giglio Island, Italy.[1][2][3] They are considered a sub-type of plastiglomerate and could possibly have negative effects on surrounding fauna by entering the food web through consumption by benthic invertebrates.[1][2][3]

Formation

Plasticrusts are formed by waves smashing plastic debris against rugose rocks.[1][2][3] A report concluded that “plasticrust abundance may depend on the local levels of nearshore plastic debris, wave exposure and tidal amplitude.”[2][3] This was based on the abundance of plasticrusts compared to the other listed factors at each location where plasticrust was detected or searched for.[2][3]

Locations

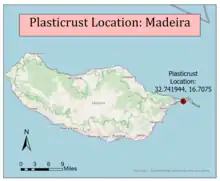

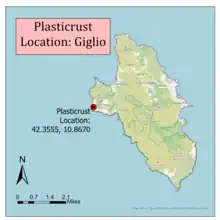

Plasticrust has so far been identified at two locations, the coasts of Madeira in the NE Atlantic Ocean and Giglio Island in the Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy, shown below in three maps.[1][2]

In Madeira, the plasticrust was found for the first time in 2016, on the south coast of the island, specifically at 32o44’31” N, 16o42’27” W.[1] The Madeira location is an isolated and off-shore island in the NE Atlantic Ocean, and is thus exposed to open waves and a tidal amplitude of 2.6 meters (8.5 feet).[2] Additionally, it has been confirmed that the plasticrust has persisted since then and that the percent coverage of the plasticrust has actually increased, based on a sampling performed in January 2019.[1]

The Giglio Island plasticrusts were found on ocean facing mid-intertidal rocks in a wave exposed rocky intertidal habitat in the Franco Promontory in western Giglio Island, Tuscan Archipelago, Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy on October 19, 2019.[2] This location, in contrast to Madeira, is a nearshore island found among other, larger, islands and the Italian mainland. Because of this, it is relatively wave sheltered. Additionally, wind speed and wave height are lower in the Tyrrhenian Sea than in the NE Atlantic and tidal amplitude is less wide at 0.45 meters (1.5 feet).[2]

Three bays were also studied in Giglio which were wave-sheltered instead of wave exposed, including Campese Bay East: 42.3657, 10.8747, Campese Bay West: 42.3700, 10.8813, and Allume Bay: 42.3528, 10.8802. However, no plasticrust was found at these locations, and this information combined with the abundance of plasticrust in Giglio relative to the abundance of plasticrust in Madeira was the basis for determining that plasticrust abundance is related to wave exposure.[2] Similarly, the difference in tidal amplitude between the two locations was the basis for the conclusion that tidal amplitude influences plasticrust abundance.[2]

Although plasticrust has so far only been identified in two locations, according to a study, their findings of plasticrust and pyroplastic, a similar type of plastic pollution, are evidence that plasticrust, among other new plastic debris types, is not a local phenomenon.[2]

Properties

The plasticrust samples from both locations were studied using fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy analysis.[1][2] The results of the analyses at each location determined that the plasticrust at both locations is composed of polyethylene, one of the most frequently used plastics worldwide.

The plasticrust identified in Madeira was found in two colors, blue and white. They had a thickness of 0.77±0.10 mm and a percent coverage as of sampling in January 2019 of 9.46±1.77.[1][3] FTIR analysis did not determine the density of the polyethylene that composed the plasticrust however, the plasticrusts off the coast of Madeira likely originate from packaging materials, such as plastic bags, which are made of low density polyethylene. The evidence for this being that pieces of marine litter found in Madeira’s coastal waters often have domestic origin.[1]

The Giglio Island plasticrusts had similar properties to those found in Madeira. They were white and blue, and they had a thickness of 0.5 to 0.7 mm.[2][3] Additionally, they covered an area of 0.46±0.08 mm2 and had a percent coverage of 0.02±0.01%.[2][3]

Potential Environmental Effects

The research done on plasticrusts at both locations suggest that plasticrust may harm surrounding fauna through microplastic particles entering the food web, specifically via consumption by benthic invertebrates such as barnacles, snails, and crabs.[1][2]

It’s been suggested that plasticrusts in Madeira may be consumed by intertidal snails (Tectarius striatus), which are found around and on top of the plasticrust. They usually eat diatoms and algae, however another species, common periwinkle, has been shown to not be able to distinguish between algae with adherent microplastics and clean algae, so according to the initial study “we cannot discard its potential grazing on plasticrusts”.[1]

In Giglio, gastropods were not found at the same location as the plasticrusts as they were in Madeira. However, marbled rock crabs, which eat algae and invertebrates, have been observed at the same elevation along the shoreline that plasticrusts were found.[2][3]

Similar Forms of Plastic Pollution

There are three other types of plastic debris pollution which are similar to plasticrust, including plastiglomerate, pyroplastic, and anthropoquina.[3]

Plastiglomerate

Plastiglomerate is melted plastic mixed with substrate to create new fragments of material with greater density.[4][3] First discovered in 2014, it is also described as “an indurated, multi-composite material made hard by agglutination of rock and molten plastic”.[4][5] It subdivides into two types, in-situ and clastic. The in-situ type is where the plastic is adhered to rock outcrops, similar to plasticrusts. The clastic type is where basalt, coral, shells, woody debris, and sand are cemented with a matrix of plastic.[4] They are often referred to as a new type of rock, but they are not defined as such due to the fact that they are anthropogenic in origin and rocks by definition from naturally.[3][5]

Pyroplastic

Pyroplastics are considered a sub-type of plastiglomerates which are formed from the melting or burning of plastic.[3][6] Similar to plasticrusts, they can be found adhered to outcrops of rock, and along the shoreline as distinct clasts which show various degrees of weathering.[6] Pyroplastics were also found on Giglio Island with the plasticrusts.[2][3]

Anthropoquina

Anthropoquinas refer to sedimentary rocks that contain objects with an anthropogenic source, which are referred to as technofossils, such as plastic fragments or metal nails, along with natural materials such as mollusk shells and siliciclastic grains.[3][7] Like plasticrusts, which are created by sea waves, the formation of anthropoquinas is not contributed to by human activity.[1][2][3] They are formed, like all sedimentary rocks, through cementation.[7]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Gestoso, Ignacio; Cacabelos, Eva; Ramalhosa, Patrício; Canning-Clode, João (October 2019). "Plasticrusts: A new potential threat in the Anthropocene's rocky shores". Science of the Total Environment. 687: 413–415. Bibcode:2019ScTEn.687..413G. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.123. PMID 31212148.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Ehlers, Sonja M.; Ellrich, Julius A. (February 2020). "First record of 'plasticrusts' and 'pyroplastic' from the Mediterranean Sea". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 151: 110845. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.110845. PMID 32056636. S2CID 211112135.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 De-la-Torre, G. E., Dioses-Salinas, D. C., Pizarro-Ortega, C. I., Santillán, I. (2021-02-01). "New plastic formations in the Anthropocene". Science of the Total Environment. 754: 142216. Bibcode:2021ScTEn.754n2216D. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142216. ISSN 0048-9697. PMID 33254855. S2CID 224958529.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 Corcoran, Patricia L.; Moore, Charles J.; Jazvac, Kelly (2014-06-01). "An anthropogenic marker horizon in the future rock record". GSA Today: 4–8. doi:10.1130/GSAT-G198A.1.

- 1 2 Corcoran, Patricia L.; Jazvac, Kelly (January 2020). "The consequence that is plastiglomerate". Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. 1 (1): 6–7. Bibcode:2020NRvEE...1....6C. doi:10.1038/s43017-019-0010-9. ISSN 2662-138X. S2CID 210169279.

- 1 2 Turner, Andrew; Wallerstein, Claire; Arnold, Rob; Webb, Delia (December 2019). "Marine pollution from pyroplastics". Science of the Total Environment. 694: 133610. Bibcode:2019ScTEn.694m3610T. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133610. hdl:10026.1/14834. PMID 31398639. S2CID 199519020.

- 1 2 Fernando, G., Elliff, C. I., Francischini, H., Dentzien-Dias, P. (2020). "Anthropoquina: First description of plastics and other man-made materials in recently formed coastal sedimentary rocks in the southern hemisphere". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 154: 111044. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111044. PMID 32174497. S2CID 212727943 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)