| Plotopterum | |

|---|---|

| |

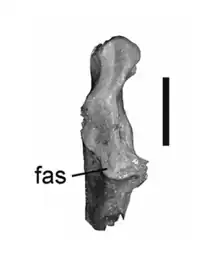

| Holotype coracoid of P. joaquinensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Suliformes |

| Family: | †Plotopteridae |

| Genus: | †Plotopterum Howard, 1969 |

| Type species | |

| Plotopterum joaquinensis Howard, 1969 | |

Plotopterum is an extinct genus of flightless seabird of the family Plotopteridae, native to the North Pacific during the Late Oligocene and the Early Miocene. The only described species is Plotopterum joaquinensis.

History and Etymology

The future holotype of Plotopterum was discovered in 1961 in the Pyramid Hill Sand member of the Jewett Sand Formation, in the San Joaquin Valley of California, by Dick Bishop and Ed Mitchell. The remains were presented by Bishop to the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County in 1964. In 1969, Hildegarde Howard, at the time retired from her work of chief curator of science at the museum, described the remains, LACM 8927, the upper end of a left coracoid, as a new genus and species, Plotopterum joaquinensis, which she ascribed to a new, monotypic family, Plotopteridae, due to its unique characteristics and adaptations towards swimming.[1]

In 1977, Hasegawa, Okumura and Okazaki described an almost complete bird femur, collected in 1976 in the Akeyo Formation in Honshu, Japan, and dated from the Early Miocene, as an indeterminate member of the family Phalacrocoracidae.[2] Less than a decade later, in 1985, Hasegawa himself, with Storrs L. Olson, redescribed the Japanese remains as belonging to the genus Plotopterum, as Plotopterum sp.[3]

Etymology

The genus name, Plotopterum, is formed from the prefix Plot-, meaning "swimming", and the suffix "-pterum", meaning wing.[1]

Description

The holotype associated with Plotopterum, the humeral end of a left coracoid, was roughly the size of those of the extant Brandt's cormorant, but narrower and more rounded. Several of its characteristics, such as the outline of the head, the shape of the bone, the scapular facet and its adjacent shaft were described as reminiscent of cormorants and anhingas. However, other characteristics, such as the head hanging over the shaft and the shape of the triosseal region, were more typical of diving birds, like penguins and auks, unrelated groups presenting flipper-like wings well adapted for swimming. The shape of the triosseal area, swollen in its lower portion and narrowed anteroposteriorly, was presumably occupied by the pectoral tendon, and strengthened the wing when the animal was swimming. Contrary to its distant relative, the flightless cormorant, the wings of Plotopterum were not reduced by the lack of use, but were heavily specialized in swimming,[1] although flightlessness can only be inferred due to the lack of well-preserved remains.[4]

The almost complete femur tentatively attributed to the genus in 1985, MFM 1800, shared similarities with Anhingidae, and the individual it belonged to was probably smaller than those of its Oligocene relatives, approximately the size of a great cormorant.[3]

Plotopterum is an outlier compared to other plotopterids. Despite being stratigraphically the youngest genus of plotopterid, most of its larger relatives going extinct at the end of the Oligocene, it seems to have kept primitive characteristics and was not as specialized for wing-propelled diving than other, older but more derived plotopterids. It has been suggested that the isolation of the ghost lineage limited to the Miocene of California and Japan to which belong Plotopterum, sister taxon to all other plotopterids from the Oligocene of the Pacific Northwest and Japan, may have permitted the preservation of basal traits.[4]

Paleoenvironment

The Pyramid Hill Sand member of the Jewett Sand Formation, where the first remains of Plotopterum were discovered, was, during the Miocene, covered by the Pacific Ocean, and has yielded, alongside the holotype of Plotopterum, numerous fossils of cetaceans, fish, turtles, and molluscs.[1] Plotopterum and its close relative Stemec are found in coastal deposits, and were possibly limited to coastal waters, while the larger Tonsalinae such as Tonsala and Copepteryx had a more pelagic lifestyle.[5]

It has been suggested that the diversification of marine mammals occurring in the Pacific Ocean during the Late Paleogene and the Early Neogene may have concurrenced the plotopterids, and participated in their extinction. During the Early Miocene, the only forms of Plotopteridae known in the fossil record, like Plotopterum, were smaller and less derived than their Oligocene counterparts, and those forms probably went extinct shortly later.[3][6]

While other genus of Plotopterids were disappearing during the Late Oligocene, Plotopterum survived well into the Miocene. This survival might be explained by the preservation into the Miocene of the offshore islands needed by plotopterids as secure breeding sites along the coast of California, when they disappeared along the coast of the Pacific Northwest during the Late Oligocene.[7]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Howard, H. (1969). "A new avian fossil from Kern County, California". The Condor. 71 (1): 68–69. doi:10.2307/1366050. JSTOR 1366050.

- ↑ Hasegawa, Y.; Okumura, Y.; Okazaki, Y. (1977). "A Miocene Bird Fossil from Mizunami, Central Japan". Bull. Mizunami Fossil Mus. 4: 119–138. doi:10.2307/1366050. JSTOR 1366050.

- 1 2 3 Olson, S. L.; Hasegawa, Y. (1985). "A Femur of Plotopterum from the Early Middle Miocene of Japan (Pelecaniformes : Plotopteridae)". Bulletin of the National Science Museum. 11 (3): 137–140. doi:10.2307/1366050. JSTOR 1366050.

- 1 2 Mayr, G.; Goedert, J. L.; Vogel, O. (2016). "New late Eocene and Oligocene remains of the flightless, penguin-like plotopterids (Aves, Plotopteridae) from western Washington State, U.S.A.". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (4): e1163573. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1163573. S2CID 88129671.

- ↑ Mayr, G.; Goedert, J. L.; De Pietri, V. L.; Scofield, R. P. (2020). "Comparative osteology of the penguin-like mid-Cenozoic Plotopteridae and the earliest true fossil penguins, with comments on the origins of wing-propelled diving". Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research. 59: 264–276. doi:10.1111/jzs.12400. S2CID 225727162.

- ↑ Olson, S. L.; Hasegawa, Y. (1979). "Fossil Counterparts of Giant Penguins from the North Pacific". Science. 4419 (206): 688–689. doi:10.1126/science.206.4419.688. PMID 17796934. S2CID 12404154.

- ↑ Goedert, J. L.; Cornish, J. (2000). "Preliminary Report on the Diversity and Stratigraphic Distribution of the Plotopteridae (Pelecaniformes) in Paleogene Rocks of Washington State, USA". In Zhou, Z.; Zhang, F. (eds.). Proceedings of the 5th symposium of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution, Beijing, 1-4 June 2000. Beijing: Science Press. pp. 63–76.