| Pokhran-II Operation Shakti | |

|---|---|

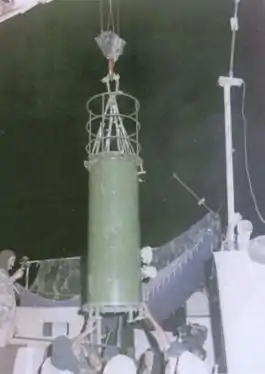

A cylindrical shaped nuclear bomb, Shakti I, prior to its detonation. | |

| Information | |

| Country | India |

| Test site | Pokhran Test Range, Rajasthan |

| Coordinates | 27°04′44″N 71°43′20″E / 27.07889°N 71.72222°E |

| Period | 11–13 May 1998[1] |

| Number of tests | 3 (5 devices fired) |

| Test type | Underground tests (underground, underground shaft) |

| Device type | Fission and Fusion |

| Max. yield | 45 kilotons of TNT (190 TJ) tested;[2]

Scale down of 200 kt model |

| Test chronology | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Legislations

Treaties and accords

Missions and agencies

Controversies

Wars and attacks

|

||

The Pokhran-II tests were a series of five nuclear bomb test explosions conducted by India at the Indian Army's Pokhran Test Range in May 1998.[3] It was the second instance of nuclear testing conducted by India; the first test, code-named Smiling Buddha, was conducted in May 1974.[4]

The tests achieved their main objective of giving India the capability to build fission and thermonuclear weapons with yields up to 200 kilotons.[2] The then-Chairman of the Indian Atomic Energy Commission described each one of the explosions of Pokhran-II to be "equivalent to several tests carried out by other nuclear weapon states over decades".[5] Subsequently, India established computer simulation capability to predict the yields of nuclear explosives whose designs are related to the designs of explosives used in this test.[2]

Pokhran-II consisted of five detonations, the first of which was a fusion bomb while the remaining four were fission bombs.[3] The tests were initiated on 11 May 1998, under the assigned code name Operation Shakti, with the detonation of one fusion and two fission bombs.[3] On 13 May 1998, two additional fission devices were detonated,[6] and the Indian government led by Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee shortly convened a press conference to declare India as a full-fledged nuclear state.[6] The tests resulted in a variety of sanctions against India by a number of major countries including Japan and the United States.

Many names have been assigned to these tests; originally these were collectively called Operation Shakti–98, and the five nuclear bombs were designated Shakti-I through to Shakti-V. More recently, the operation as a whole has come to be known as Pokhran-II, and the 1974 explosion as Pokhran-I.[7]

India's nuclear bomb project

Efforts towards building the nuclear bomb, infrastructure, and research on related technologies have been undertaken by India since World War II. Origins of India's nuclear program date back to 1944 when nuclear physicist Homi Bhabha began persuading the Indian National Congress towards the harnessing of nuclear energy— a year later he established the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR).[8]

In 1950s, the preliminary studies were carried out at the BARC and plans were developed to produce plutonium and other bomb components. In 1962, India and China engaged in the disputed northern front, and was further intimidated with a Chinese nuclear test in 1964. Direction towards militarisation of the nuclear program slowed down when Vikram Sarabhai became its head and Lal Bahadur Shastri showed little interest after becoming the Prime Minister in that year.[8]

After Indira Gandhi became Prime Minister in 1966, the nuclear program was consolidated when physicist Raja Ramanna joined the efforts. Another nuclear test by China eventually led to India's decision to build nuclear weapons in 1967 and conduct its first nuclear test, Smiling Buddha, in 1974.[9]

Post-Smiling Buddha

Responding to Smiling Buddha,[10] the Nuclear Suppliers Group severely affected India's nuclear program.[11] The world's major nuclear powers imposed technological embargo on India and Pakistan, which was on its own technological race to match India's achievement.[11] The nuclear program struggled for years to gain credibility and its progress was crippled by the lack of indigenous resources and dependence on imported technology and technical assistance.[11] Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared to the IAEA that India's nuclear program was not for military purposes, despite authorising preliminary work on the hydrogen bomb design.[11]

In the aftermath of the state emergency in 1975 that resulted in the collapse of the Prime Minister Indira Gandhi's government, the nuclear program was left in a vacuum, lacking political leadership and even basic management.[11] Work on the hydrogen bomb design continued under M. Srinivasan, a mechanical engineer, but progress was slow.[11]

The nuclear program received little attention from Prime Minister Morarji Desai who was renowned for his peace advocacy.[11] In 1978, Prime Minister Desai transferred physicist Ramanna to Indian MoD, and his government once again accelerated India's nuclear program.[11][12]

Shortly thereafter, the world discovered the Pakistan's clandestine atomic bomb program.[11] Contrary to India's nuclear program, Pakistan's atomic bomb program was akin to United States Manhattan Project, in that it was under military oversight with civilian scientists in charge of the scientific aspects of the program.[11] The Pakistan's secretive atomic bomb program was well funded and organised; India realised that Pakistan was very likely to succeed in its project in matter of two years.[11]

In 1980, the general elections marked the return of Indira Gandhi and the nuclear program began to gain momentum under Ramanna in 1981. Requests for additional nuclear tests continued to be denied by the government after Prime Minister Indira Gandhi saw Pakistan begin engaging in brinkmanship, though the nuclear program continued to advance.[11] Work towards the hydrogen bomb, as well as the launch of the missile programme, began under Dr. A.P.J Abdul Kalam, who was then an aerospace engineer.[11]

Political momentum: 1988–1998

In 1989, the general elections witnessed the Janata Dal party led by V.P. Singh, forming the government.[13] Prime Minister V.P. Singh downplayed the relations with the Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto whose Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) won the general elections in 1988. Foreign relations between India and Pakistan severely worsened when India accused Pakistan of supporting the Insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir.[13] During this time, the Indian Missile Program succeeded in the development of the Prithvi missiles.

Successive governments in India decided to observe this temporary moratorium for fear of inviting international criticism.[11] The Indian public had supported the nuclear tests which ultimately led Prime Minister Narasimha Rao deciding to conduct further tests in 1995.[13] Plans were halted after American spy satellites picked up signs of preparations for nuclear testing at Pokhran Test Range in Rajasthan.[13] President Bill Clinton and his administration exerted enormous pressure on Prime Minister Narasimha Rao to stop the preparations.[13] Responding to India, Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto issued harsh criticism towards India on Pakistan's news channels; thus putting stress on the relations between two countries.[14]

Diplomatic tensions escalated between India and Pakistan when Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto raised the Kashmir issue at the United Nations in 1995.[15][16][17] In a speech delivered by then-Speaker of the National Assembly of Pakistan, Yousaf Raza Gillani, stressed the "Kashmir problem" as a continuing threat to peace and security in the region.[17] The Indian delegation headed by Atal Bihari Vajpayee at the United Nations, reiterated that the "UN resolutions only call upon Pakistan— the occupying force to vacate the "Jammu and Kashmir Area."[17]

1998 Indian general elections

The BJP, came to power in 1998 general elections with an exclusive public mandate.[6] BJP's political might had been growing steadily in strength over the past decade over several issues.

In Pakistan, the similar conservative force, the PML(N), was also in power with an exclusive mandate led by Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif who defeated the leftist PPP led by Benazir Bhutto in the general elections held in 1997.[18] During the BJP campaign, Atal Bihari Vajpayee indulged in grandstanding— such as when he declared on 25 February that his government would "take back that part of Kashmir that is under Pakistan's control."[6] Before this declaration, the BJP platform had clear intentions to "exercise the option to induct nuclear weapons" and "India should become an openly nuclear power to garner the respect on the world stage that India deserved."[6] By 18 March 1998, Vajpayee publicly began lobbying for nuclear testing and declared that "there is no compromise on national security; all options including the nuclear options will be exercised to protect security and sovereignty."[6]

Consultation began between Prime Minister Vajpayee, Dr.Abdul Kalam, R. Chidambaram and officials of the Indian DAE on nuclear options. Chidambaram briefed Prime Minister Vajpayee extensively on the nuclear program; Abdul Kalam presented the status of the missile program. On 28 March 1998, Prime Minister Vajpayee asked the scientists to make preparations in the shortest time possible, and preparations were hastily made.[19]

Pakistan, at a Conference on Disarmament, said it would offered a peace agreement with India for "an equal and mutual restraint in conventional, missile and nuclear fields."[6] Pakistan's equation was later reemphasised on 6 April and the momentum in India for nuclear tests began to build up which strengthened Vajpayee's position to order the tests.[6]

Preparations for the test

Unlike Pakistan's weapon–testing laboratories, there was very little that India could do to hide its activity at Pokhran.[20] Unlike the high-altitude granite mountains in Pakistan, the bushes are sparse and the dunes in the Rajasthan Desert provide little cover from probing satellites.[20] The Indian Intelligence Bureau had been aware of United States spy satellites and the CIA had been detecting Indian test preparations since 1995. Therefore, the tests required complete secrecy in India and also needed to avoid detection by other countries.[20] The 58th Engineer Regiment of the Indian Army Corps of Engineers was commissioned to prepare the test sites to avoid detection by the United States spy satellites. The 58th Engineer's commander Colonel Gopal Kaushik supervised the test preparations and ordered his "staff officers take all measures to ensure total secrecy."[20]

Extensive planning was done by a small group of scientists, senior military officers and senior politicians to ensure that the test preparations would remain secret, and even senior members of the Indian government did not know what was going on. The chief scientific adviser and the Director of Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), Dr. Abdul Kalam, and Dr. R. Chidambaram, the director of the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE), were the chief coordinators of this test planning.[6] The scientists and engineers of the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC), the Atomic Minerals Directorate for Exploration and Research (AMDER), and the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) were involved in the nuclear weapon assembly, layout, detonation and data collection.[6] A small group of senior scientists were involved in the detonation process. All scientists were required to wear army uniforms to preserve the secrecy of the tests. Since 1995, the 58th Engineer Regiment had learned how to avoid satellite detection.[6] Work was mostly done during night, and equipment was returned to the original place to give the impression that it was never moved.[6]

Bomb shafts were dug under camouflage netting and the dug-out sand was shaped like dunes. Cables for sensors were covered with sand and concealed using native vegetation.[6] Scientists would not depart for Pokhran in groups of two or three.[6] They travelled to destinations other than Pokhran under pseudonyms, and were then transported by the army. Technical staff at the test range wore military uniforms, to prevent detection in satellite images.[20]

Nuclear weapon designs and development

Development and test teams

The main technical personnel involved in the operation were:[21]

- Project Chief Coordinators :

- Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam (later, President of India), scientific adviser to the prime minister and head of the DRDO.

- Dr. R. Chidambaram, chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission and the Department of Atomic Energy.

- Defence Research & Development Organization (DRDO) :

- Dr. K. Santhanam; director, test site preparations.

- Atomic Minerals Directorate for Exploration and Research :

- Dr. G. R. Dikshitulu; senior research scientist B.S.O.I Group, Nuclear Materials Acquisition.

- Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) :

- Dr. Anil Kakodkar, director of BARC.

- Dr. Satinder Kumar Sikka, director; Thermonuclear Weapon Development.

- Dr. M. S. Ramakumar, director of Nuclear Fuel and Automation Manufacturing Group; Director, Nuclear Component Manufacture.

- Dr. D.D. Sood, director of Radiochemistry and Isotope Group; director, Nuclear Materials Acquisition.

- Dr. S.K. Gupta, Solid State Physics and Spectroscopy Group; director, Device Design & Assessment.

- Dr. G. Govindraj, associate director of Electronic and Instrumentation Group; director, field instrumentation.

Movement and logistics

Three laboratories of the DRDO were involved in designing, testing and producing components for the bombs, including the advanced detonators, the implosion and high-voltage trigger systems. These were also responsible for weaponising, systems engineering, aerodynamics, safety interlocks and flight trials.[21] The bombs were transported in four Indian Army trucks under the command of Colonel Umang Kapur; all devices from BARC were relocated at 3 am on 1 May 1998. From the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj International Airport, the bombs were flown in an Indian Air Force's AN-32 commanded by Squadron Leader Mahendra Prasad Sharma to Jaisalmer. They were transported to Pokhran in an army convoy of four trucks, and this required three trips. The devices were delivered to the device preparation building, which was designated as 'Prayer Hall'.[21]

The test sites was organised into two government groups and were fired separately, with all devices in a group fired at the same time. The first group consisted of the thermonuclear device (Shakti I), the fission device (Shakti II), and a sub-kiloton device (Shakti III). The second group consisted of the remaining two sub-kiloton devices Shakti IV and V. It was decided that the first group would be tested on 11 May and the second group on 13 May. The thermonuclear device was placed in a shaft code named 'White House', which was over 200 metres (660 ft) deep, the fission bomb was placed in a 150 metres (490 ft) deep shaft code named 'Taj Mahal', and the first sub-kiloton device in 'Kumbhkaran'. The first three devices were placed in their respective shafts on 10 May, and the first device to be placed was the sub-kiloton device in the 'Kumbhkaran' shaft, which was sealed by the army engineers by 8:30 pm. The thermonuclear device was lowered and sealed into the 'White House' shaft by 4 am, and the fission device being placed in the 'Taj Mahal' shaft was sealed at 7:30 am, which was 90 minutes before the planned test time. The shafts were L-shaped, with a horizontal chamber for the test device.[21]

The timing of the tests depended on the local weather conditions, with the wind being the critical factor. The tests were underground, but due to a number of shaft seal failures that had occurred during tests conducted by the United States, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom, the sealing of the shaft could not be guaranteed to be leak-proof. By early afternoon, the winds had died down and the test sequence was initiated. Dr. K. Santhanam of the DRDO, in charge of the test site preparations, gave the two keys that activated the test countdown to Dr. M. Vasudev, the range safety officer, who was responsible for verifying that all test indicators were normal. After checking the indicators, Vasudev handed one key each to a representative of BARC and the DRDO, who unlocked the countdown system together. At 3:45 pm the three devices were detonated.[21]

Specifications and detonation

Five nuclear devices were tested during Operation Shakti.[22] Four of the devices were weapon-grade plutonium[21] and one Thorium/U-233. They were:[21][2]

- Shakti I: A thermonuclear device yielding 56 kt, but designed for up to 200 kt.[2] The yield of this device was deliberately kept low in order to avoid civilian damage and to eliminate the possibility of a radioactive leak.[2]

- Shakti II: A plutonium implosion design yielding 15 kt and intended as a warhead that could be delivered by bomber or missile. It was an improvement of the device detonated in the 1974 Smiling Buddha (Pokhran-I) test of 1974, developed using simulations on the PARAM supercomputer.

- Shakti III: An experimental linear implosion design that used "non-weapon grade"[23] plutonium, but which likely omitted the material required for fusion, yielding 0.3 kt.

- Shakti IV: A 0.5 kt experimental device.

- Shakti V: A 0.2 kt Thorium/U-233 experimental device.

An additional, sixth device (Shakti VI) is suspected to have been present but not detonated.[21]

At 3:43 pm IST; three nuclear bombs (specifically, the Shakti I, II and III) were detonated simultaneously, as measured by international seismic monitors.[6] On 13 May, at 12.21 p.m. IST (6:51 UTC), two sub-kiloton devices (Shakti IV and V) were detonated. Due to their very low yield, these explosions were not detected by any seismic station.[6] On 13 May 1998, India declared the series of tests to be over after this.[24]

Announcement

Having tested weaponized nuclear warheads in the Pokhran-II series, India became the sixth country to join the nuclear club.[25] Shortly after the tests, a press meet was convened at the Prime Minister's residence in New Delhi. Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee appeared before the press corps and made the following short statement:

Today, at 15:45 hours, India conducted three underground nuclear tests in the Pokhran range. The tests conducted today were with a fission device, a low yield device and a thermonuclear device. The measured yields are in line with expected values. Measurements have also confirmed that there was no release of radioactivity into the atmosphere. These were contained explosions like the experiment conducted in May 1974. I warmly congratulate the scientists and engineers who have carried out these successful tests.[26][27]

Reactions to tests

Domestic reactions

News of the tests were greeted with jubilation and large-scale approval by society in India.[28] The Bombay Stock Exchange registered significant gains. Newspapers and television channels praised the government for its bold decision; editorials were full of praise for the country's leadership and advocated the development of an operational nuclear arsenal for the country's armed forces.[28] The Indian opposition, led by Indian National Congress criticised the Vajpayee administration for carrying out the series of nuclear tests. The INC spokesperson Salman Khursheed, accused the BJP of trying to use the tests for political ends rather than to enhance the country's national security.[28]

By the time India had conducted tests, the country had a total of $44bn in loans in 1998, from the IMF and the World Bank.[29] The industrial sectors of the Indian economy, such as the chemicals industry, were likely to be hurt by sanctions.[29] The Western consortium companies, which had invested heavily in India, especially in construction, computing and telecoms, were generally the ones who were harmed by the sanctions.[29] In 1998, Indian government announced that it had already allowed for some economic response and was willing to take the consequences.[29]

International reactions

Canada, Japan, and other countries

Strong criticism was drawn from Canada on India's actions and its High Commissioner.[30] Sanctions were also imposed by Japan on India and consisted of freezing all new loans and grants except for humanitarian aid to India.[31]

Some other nations also imposed sanctions on India, primarily in the form of suspension of foreign aid to India and government-to-government credit lines.[32] However, the United Kingdom, France, and Russia refrained from condemning India.[32]

China

On 12 May the Chinese Foreign Ministry stated: "The Chinese government is seriously concerned about the nuclear tests conducted by India," and that the tests "run counter to the current international trend and are not conducive to peace and stability in South Asia.".[33] The next day the Chinese Foreign Ministry issued the statement clearly stating that "it is shocked and strongly condemned" the Indian nuclear tests and called for the international community to "adopt a unified stand and strongly demand that India immediate stop development of nuclear weapons".[34] China further rejected India's stated rationale of needing nuclear capabilities to counter a Chinese threat as "totally unreasonable".[34] In a meeting with Masayoshi Takemura of Democratic Party of Japan, Foreign Minister of the People's Republic of China Qian Qichen was quoted as saying that India's nuclear tests were a "serious matter," particularly because they were conducted in light of the fact that more than 140 countries have signed the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. "It is even more unacceptable that India claims to have conducted the tests to counter what it called a "China threat".[34] On 24 November 1998, the Chinese Embassy, New Delhi issued a formal statement:

(sic).... But regrettably, India conducted nuclear tests last May, which has run against the contemporary historical trend and seriously affected peace and stability in South Asia. Pakistan also conducted nuclear tests later on. India's nuclear tests have not only led to the escalation of tensions between India and Pakistan and provocation of nuclear arms races in South Asia, but also dealt a heavy blow to international nuclear disarmament and the global nonproliferation regime. It is only natural that India's nuclear tests have met with extensive condemnation and aroused serious concern from the international community.

Pakistan

The most vehement and strong reaction to India's nuclear explosion was from a neighbouring country, Pakistan. Great ire was raised in Pakistan, which issued a severe statement blaming India for instigating a nuclear arms race in the region.[6] Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif vowed that his country would give a suitable reply to India.[6] The day after the first tests, Foreign Minister Gohar Ayub Khan indicated that Pakistan was ready to conduct a nuclear test. He stated: "Pakistan is prepared to match India, we have the capability.... We in Pakistan will maintain a balance with India in all fields", he said in an interview. "We are in a headlong arms race on the subcontinent."[6]

On 13 May 1998, Pakistan bitterly condemned the tests, and Foreign Minister Gohar Ayub was quoted as saying that Indian leadership seemed to "have gone berserk [sic] and was acting in a totally unrestrained way."[36] Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif was much more subdued, maintaining ambiguity about whether a test would be conducted in response: "We are watching the situation and we will take appropriate action with regard to our security", he said.[6] Sharif sought to mobilise the entire Islamic world in support of Pakistan and criticised India for nuclear proliferation.[6]

Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif had been under intense pressure regarding the nuclear tests by US President Bill Clinton and Opposition leader Benazir Bhutto at home.[37] Initially surprising the world, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif authorised a nuclear testing program and the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) carried out nuclear testing under the codename Chagai-I on 28 May 1998 and Chagai-II on 30 May 1998. These six underground nuclear tests at the Chagai and Kharan test site were conducted fifteen days after India's last test. The total yield of the tests was reported to be 40 kt (see codename: Chagai-I).[38]

Pakistan's subsequent tests invited similar condemnation from the United States.[39] American President Bill Clinton was quoted as saying "Two wrongs don't make a right", criticising Pakistan's tests as reactionary to India's Pokhran-II.[37] The United States and Japan reacted by imposing economic sanctions on Pakistan. According to the Pakistan's science community, the Indian nuclear tests gave an opportunity to Pakistan to conduct nuclear tests after 14 years of conducting only cold tests (See: Kirana-I).[40]

Pakistan's leading nuclear physicist, Pervez Hoodbhoy, held India responsible for Pakistan's nuclear test experiments in Chagai.[41]

United States

The United States issued a strong statement condemning India and promised that sanctions would follow. The American intelligence community was embarrassed as there had been "a serious intelligence failure of the decade" in detecting the preparations for the test.[42]

In keeping with its preferred approach to foreign policy in recent decades, and in compliance with the 1994 anti-proliferation law, the United States imposed economic sanctions on India.[43] The sanctions on India consisted of cutting off all assistance to India except humanitarian aid, banning the export of certain defence material and technologies, ending American credit and credit guarantees to India, and requiring the US to oppose lending by international financial institutions to India.[44]

From 1998 to 1999, the United States held series of bilateral talks with India over the issue of India becoming a part of the CTBT and NPT.[45] In addition, the United States also made an unsuccessful attempt of holding talks regarding the rollback of India's nuclear program.[46] India took a firm stand against the CTBT and refusing to become a signatory of it despite under pressure by the US President Bill Clinton, and noted the treaty as it was not consistent with India's national security interest.[46]

UN condemnation

The reactions from abroad started immediately after the tests were advertised. On 6 June, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1172, condemning the Indian and the Pakistani tests.[47] China issued a vociferous condemnation calling upon the international community to exert pressure on India to sign the NPT and to eliminate its nuclear arsenal. With India joining the group of countries possessing nuclear weapons, a new strategic dimension had emerged in Asia, particularly in South Asia.[47]

Legacy

The Indian government has officially declared 11 May as National Technology Day in India to commemorate the first of the five nuclear tests that were carried out on 11 May 1998.[48]

It was officially signed by then-Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee in 1998 and the day is celebrated by giving awards to various individuals and industries in the field of science and technology.[48]

In popular culture

- Parmanu: The Story of Pokhran is a 2018 Bollywood movie based on India's underground Pokhran-II nuclear tests.[49]

- War and Peace: A documentary by Anand Patwardhan.[50]

See also

- India and weapons of mass destruction

- Pokhran-I—First nuclear test explosion by India on 18 May 1974

References

- ↑ Ganguly, Sumit (1999). "India's Pathway to Pokhran II: The Prospects and Sources of New Delhi's Nuclear Weapons Program". International Security. 23 (4): 148–177. doi:10.1162/isec.23.4.148. ISSN 0162-2889. JSTOR 2539297. S2CID 57565560.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Press Statement by Dr. Anil Kakodkar and Dr. R. Chidambaram on Pokhran-II tests". Press Information Bureau, Government of India. 24 September 2009. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 CNN India Bureau (17 May 1998). "India releases pictures of nuclear tests". CNN India Bureau. CNN India Bureau. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

{{cite news}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ↑ "Official press release by India". meadev.gov.in/. Ministry of External Affairs, 1998. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ↑ "We have an adequate scientific database for designing ... a credible nuclear deterrent". Frontline. 16. 2–15 January 1999. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 "The nuclear politics: The 1998 Election". Nuclear weapon archives. Nuclear politics. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ↑ "Why May 11 be celebrated as National Technology Day? Things you should know". Times of India. 11 May 2020.

- 1 2 "Homi Bhabha and how World War II was responsible for creating India's nuclear future". The print. 30 October 2019.

- ↑ Bates, Crispin (2007). Subalterns and Raj: South Asia Since 1600. Routledge. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-415-21484-1.

- ↑ "Smiling Buddha: All about Pokhran test that made India a nuclear power". The Indian Hawk | Indian Defence News. 19 May 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Sublette, Carey. "The Long Pause: 1974–1989". nuclearweaponarchive.org. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ↑ Chengappa, Raj (2000). Weapons of peace : the secret story of India's quest to be a nuclear power. New Delhi: Harper Collins Publishers, India. pp. 219–220. ISBN 81-7223-330-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 weapon archive. "The Momentum builds". Nuclear weapon Archive. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ↑ "India wants to divert attention from N-test plan". Dawn Archives. CNN. 4 January 1996. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ↑ "UN General Assembly—11th Meeting official records" (PDF). documents-dds-ny.un.org. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ↑ Team, ODS. "UN General Assembly—10th Meeting official records" (PDF). documents-dds-ny.un.org. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 Masood Haider (5 September 1995). "Pakistan's raising of Kashmir issue upsets India". Dawn. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ↑ See: 1997 Pakistani general elections

- ↑ (PTI), Press Trust of India (September 2009). "Pokhran II row: Sethna slams Kalam, Iyengar says tests were done in haste". DNA News. dna news. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Books: Weapons of Peace—How the CIA was Fooled". India Today. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "India's Nuclear Weapons Program—Operation Shakti: 1998". 30 March 2001. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ "Forces gung-ho on N-arsenal". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ Note: While the plutonium used in Shakti III has been reported in some sources as "reactor-grade", it may have been fuel-grade, which is intermediate between the former and weapons-grade; cf. Why You Can’t Build a Bomb From Spent Fuel Archived 20 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Press Release (13 May 1998). "Planned Series of Nuclear Tests Completed". Indian Government. Ministry of External Affairs. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ BBC Report (13 May 1998). "Asia's nuclear challenge: Third World joins the nuclear club". BBC India 1998. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ "Prime Minister's announcement of India's three underground nuclear tests". Fas.org. Archived from the original on 14 March 2002. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ↑ "Prime Minister's press briefing video". YouTube.

- 1 2 3 Lyon, David (31 May 1998). "India detonates two more bombs". BBC India, 1998 (Follow up). Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 BBC Reports (1 June 1998). "India—will sanctions bite?". BBC Economic review. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ Haidar, Suhasini (31 August 2014). "East meets Far East". The Hindu.

- ↑ "U.S. lifts final sanctions on Pakistan". CNN. 29 October 2001. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012.

- 1 2 Charan D. Wadhva (27 June – 3 July 1998). "Costs of Economic Sanctions: Aftermath of Pokhran II". Economic and Political Weekly. 33 (26): 1604–1607. JSTOR 4406922.

- ↑ "China is 'Seriously Concerned' But Restrained in Its Criticism". New York Times, 13 May 1998. 13 May 1998.

- 1 2 3 Resources on India and Pakistan (1999). "China's Reaction to India's Nuclear Tests". CNS Center for Nonproliferation Studies Monterey Institute of International Studies. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ↑ Active Correspondents (24 November 1998). "India-China Claim 'active approach". The Hindu, 24/xi-1998.

- ↑ Special Report (13 May 1998). "Pakistan condemns India's nuclear tests". BBC Pakistan. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- 1 2 Gertz, Bill (2013). Betrayal: How the Clinton Administration Undermined American Security. Washington DC: Regnery Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62157-137-7.

- ↑ See Chagai-I

- ↑ "cns.miis.edu". Archived from the original on 18 November 2001. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ↑ "Pakistan's tests". Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ↑ Hoodbhoy, Pervez Amerali (23 January 2011). "Nuclear Bayonet". The Herald.

- ↑ Weiner, T. (13 May 1998). "Nuclear anxiety: The Blunders; U.S. Blundered On Intelligence, Officials Admit". The New York Times.

- ↑ BBC Release (13 May 1998). "US imposes sanctions on India". BBC America. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ "U.S. imposes sanctions on India". CNN.

- ↑ Chandrasekharan, S. "CTBT : where does India stand?". southasiaanalysis.org/. South Asia analysis. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- 1 2 "Clarifying India's Nascent Nuclear Doctrine". armscontrol.org/. arms control interview. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- 1 2 Dittmer, L., ed. (2005). South Asia's nuclear security dilemma: India, Pakistan, and China. Armonk, NY: Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1419-3.

- 1 2 Press Information Bureau (11 May 2008). "National technology day celebrated". Department of Science and Technology. Archived from the original on 15 December 2010. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ↑ Ghosh, Samrudhi (14 August 2017). "John Abraham unveils Parmanu poster: All you need to know about the story of Pokhran". India Today. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ↑ SatyaShodak (18 December 2017), War and Peace—Anand Patwardhan, retrieved 1 June 2019

External links

- Nuclear Weapons Archive: Operation Shakti

- India aborted nuclear bomb plans in 1994

- Sumit Ganguly (Spring 1999). "India's Pathway to Pokhran II: The Prospects and Sources of New Delhi's Nuclear Weapons Program". International Security. 23 (4): 148–177. doi:10.1162/isec.23.4.148. JSTOR 2539297. S2CID 57565560.

- Chengappa, Raj. "How the CIA Was Fooled" (Weapons of peace). India Today. Retrieved 24 June 2012.