| Federal republic | |

Prinsenvlag to 1630/1664, Statenvlag (from 1630/1664) | |

| Formation | 23 January 1579 |

|---|---|

| Extinction | 19 January 1795 |

| Founding document | Union of Utrecht |

| State | Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden |

| Country | Netherlands |

| Legislative branch | |

| Legislature | States General |

| Meeting place | The Hague (de facto) |

| Executive branch | |

| Default Executive | Stadholder |

| Main body | Council of State |

| Default Executive | Councilor Pensionary of Holland |

| Appointed by | States of Holland (see below) |

| Headquarters | The Hague |

| Main organ | Executive |

| Departments | Rekenkamer, States Army, Dutch admiralties |

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

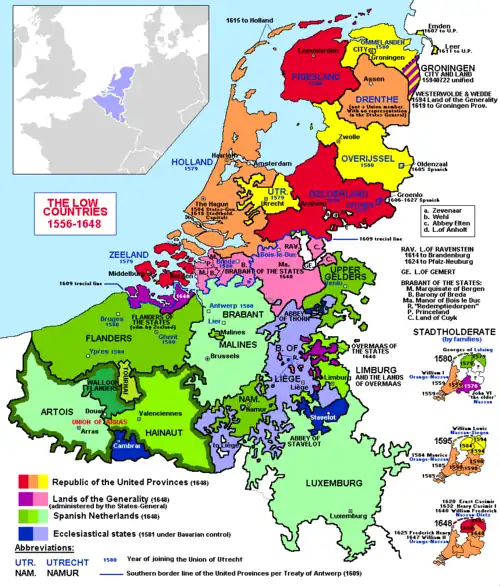

The Dutch Republic existed from 1579 to 1795 and was a confederation of seven provinces, which had their own governments and were very independent, and a number of so-called Generality Lands. These latter were governed directly by the States-General (Staten-Generaal in Dutch), the federal government. The States-General were seated in The Hague and consisted of representatives of each of the seven provinces.

Overview

When several provinces and cities in rebellion against Philip II of Spain declared themselves independent in 1581 with the Act of Abjuration, they initially aspired to appoint another prince as head of state. The sovereignty of the provinces was first offered to Francis, Duke of Anjou, but his 1583 coup d'état was foiled and he was ousted. After the assassination of rebel leader William the Silent, it was offered in turn to and declined by Henry III of France and Elizabeth I of England. Elizabeth did make the provinces an English protectorate and sent over the Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester as governor-general (Treaty of Nonsuch, 1585). For many reasons, it was not a success, and Leicester left in 1588. This left the provinces in rebellion without a head.

The provinces of the republic were, in official feudal order: the duchy of Guelders (Gelre in Dutch), the counties of Holland and Zeeland, the former bishopric of Utrecht, the lordship of Overijssel, and the free (i.e. never feudalised) provinces of Friesland and Groningen. In fact there was an eighth province, the lordship of Drenthe, but this area was so poor it was exempt from paying confederal taxes and, as a corollary, was denied representation in the States-General. The duchy of Brabant, the county of Flanders and the lordship of Mechelen were also among the rebelling provinces, but were later completely or largely reconquered by Spain. After the Peace of Westphalia, the parts of these provinces that remained in the Dutch Republic's hands, as well as several other border territories, became confederally governed Generality Lands (Generaliteitslanden). They were Staats-Brabant (present North Brabant), Staats-Vlaanderen (present Zeelandic Flanders), Staats-Overmaas (around Maastricht) and Staats-Opper-Gelre (around Venlo, after 1715).

The republican form of government was not democratic in the modern sense; in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, the "regents" or regenten formed the ruling class of the Dutch Republic, the leaders of the Dutch cities or the heads of organisations (e.g. "regent of an orphanage"). Since the late Middle Ages Dutch cities had been run by the richer merchant families. Although not formally a hereditary "class", they were de facto "patricians", comparable in some sense to that ancient Roman class. At first the lower-class citizens in the guilds and schutterijen could unite to form a certain counterbalance to the regenten, but in the course of the 16th, 17th and 18th century the administration of the cities and towns became oligarchical in character, and it became harder and harder to enter their caste. From the latter part of the 17th century the regent families were able to reserve government offices to themselves via quasi-formal contractual arrangements. Most offices were filled by co-option for life. Thus the regent class tended to perpetuate itself into a closed class. However, in practice they had to take into account the opinions of the man on the street (de gemeente Dutch), moreso than in the monarchies of the time, otherwise they ran the risk of being dislodged by political upheavals, like the Orangist revolutions of 1672 and 1747 and the Patriot revolt of 1785.[1]: 135 · [2] : 78 · [3] : 94 It was, by the standards of the time, a country where men lived safely under the laws.[1]: 135 · [4]

Preponderance of Holland

Historically, Holland was by far the most populous and prosperous of the provinces north of the rivers. Even today people use the term Holland colloquially to refer to the provinces of North Holland and South Holland as well as the Kingdom of the Netherlands in general. This was true in the past also, and is due to the predominance of the province of Holland in population, resources and industry north of the great river estuaries of the Rhine and the Meuse (Dutch: Maas).[5]: 277

Holland's hegemony over the other provinces north of the Rhine and the Maas that would form the Dutch Republic is a culmination of trends reaching back to the thirteenth century.[5]: 277 (see also Northwestern Regional Center and Amsterdam-region) The Dutch Revolt removed the counterweights that had historically kept Holland in check from the fifteenth century: the relatively more prosperous commerce of Flanders and Brabant/Antwerp and the centralising tendencies of the Burgundian and Habsburg rulers.[5]: 277 Hollandish hegemony north of the Rhine/Maas delta was contested for a while by the Duchy of Gelderland (see Guelders Wars), but was unsuccessful due to the resources of Holland and their Habsburg rulers.

The center of the Dutch Revolt was initially in the southern Netherlands. The influence of William the Silent and Leicester also checked Holland. With Leicester's departure, and the reconquest of the southern Netherlands as well as large parts of the north by the Duke of Parma, there was no longer any countervailing influence.[5]: 277 The wide river barriers formed by the confluence of the Rhine and Meuse rivers offered a formidable barrier to reconquest of the core of the Dutch Revolt, now in Holland, when defended by a determined army under a capable leader (Prince Maurice of Nassau, William III). Much of the commerce that had fueled the growth of Flanders and Brabant also fled north to Holland during the upheavals of the revolt. So, at the formative stages of the Dutch Republic's institutions, from 1588 through roughly the next 20 years there was no other power that had any leverage over Holland.[5]: 277 Holland built the Republic and its institutions on the basis of sovereign provincial rights. However, only Holland could fully utilise them. It employed the lesser provinces, as they were reconquered, to bolster her defenses and economic resources. The States General had powers over foreign policy, and war and peace. It extended its decisions, especially after 1590, to inter-provincial matters such as regulation of shipping, administration of the conquered lands, church affairs, and colonial expansion. This framework was largely built and imposed by Holland, sometimes over the objections of the other provinces.[5]: 277

This is not to say that the institutions of the Republic were completely Holland-centric. In matters of form and ceremony the seven voting provinces were equal and sovereign in their own houses. The Union of Utrecht and the States General that gave it substance and form were not intended to function as a federal state. The provinces were supposed to take important decisions unanimously. So the intent of the Union of Utrecht was a confederacy of states. What emerged due to circumstances after 1579 was more a sovereign federation of sovereign states (a formulation borrowed by the United States of America). The rule of unanimity was largely unworkable: the decision to back William III's invasion of England in 1688 was a notable exception. Principle decisions, however, were seldom, if ever, taken over the objections of Holland. In the same way, Holland, in the interests of harmony, would not try, once the other provinces were reconstituted and rejoined to the Union, to take a decision over the strenuous objections of the other provinces, but would try to build a majority consensus on major decisions.[5]: 277 ;[2]: 64 Within these constraints, as seen below, a persuasive Councillor Pensionary of Holland and/or a Stadholder/Prince of Orange could move the provinces to a consensus.[2]: 83 · [3]: 134–135 · [1]: 56

National government

Republic or Republics

The Union of Utrecht was more a defensive treaty against Spain and Phillip II than an actual constitution in the modern sense. It was a defensive alliance between sovereign states. Each province remained the master in their own "house" and only ceded those powers to the States General that were necessary for the maintenance of the collective peace and security. After the Act of Abjuration, the sovereignty in each province reverted to the States (see below) of that province, so that each was a separate republic in its own right.

This is how the contemporaries thought of themselves. The Dutch formulation of the official name of the Republic is the United Provinces or the Seven United Provinces, in plural, using in the Dutch the plural for the reference. Another formulation sometimes used is one that sounds familiar in the modern day, the United States of the Netherlands. This was repeated in Latin by Johan de Witt, the famous Raadpensionaris of Holland. The country was referred to in the plural as respublicae federate or unitae (in the plural), and not respublica (in the singular), which would be correct for a unitary state.[1]: 58 The usual colloquial English formulation of the Dutch Republic is, then, strictly, incorrect.

States-General

The States-General (Staten-Generaal in Dutch) or the Generality (Generaliteiten) for short was a descendant of the medieval Burgundian and Habsburg States-Generals. In medieval times and under the Habsburgs, they met infrequently to discuss matters of common interest and to vote taxes for the benefit of the Dukes of Burgundy and their Habsburg heirs.[6]: vol 1 [5]: 292 At first the States-General was thought of as an extraordinary body.[2]: 67 After the abjuration of the king in 1581 and the separation of the northern Netherlands from the Spanish dominions, the States-General replaced the king as the supreme authority and as the central government of the northern Netherlands, which then became known as the United Provinces. As alluded to above, this was an ad hoc arrangement since no prince would anger Spain by accepting sovereignty over the provinces. As the years went by, and the confidence of the governing regents and Princes of Orange grew, the desire to be ruled by a foreign prince diminished.[7]: 29 From 1593, the States-General met daily, including on Sundays, usually between 11 and 1, and, after some variation in the earlier years, it came to sit in the Binnenhof, in The Hague, near the States of Holland.[2]: 67

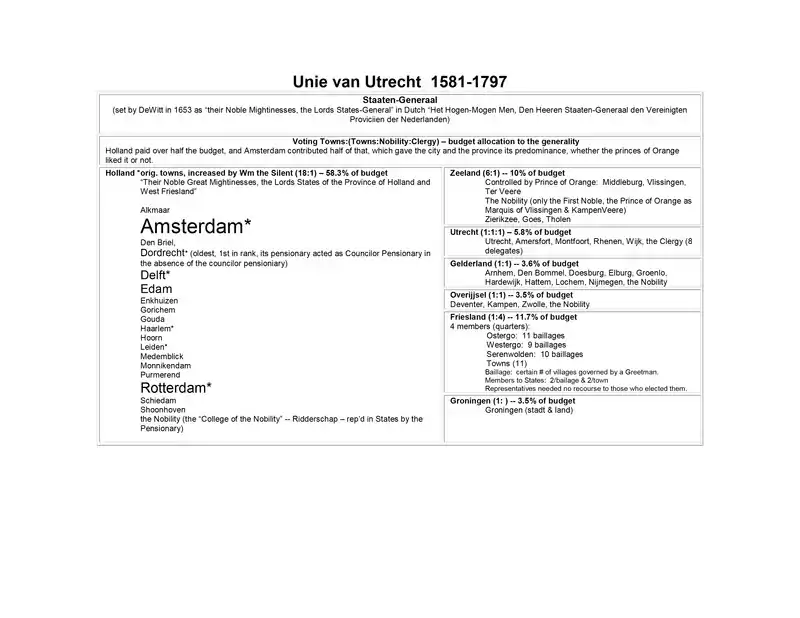

The style of address to the States-General was codified by Johan de Witt in 1653 as "their High Mightinesses, the Lords States-General" or, in Dutch, De Heeren Hoog-Mogenden, De Heeren Staten-Generaal der Verenigde Provinciën der Nederlanden).[1]: 57

Each province was allowed one vote in the States-General, and the Republic continued this practice. Each province could send as many representatives as they chose. However, the size of the meeting room limited the size of the delegations. The representatives were appointed for a term by the provincial estates and were not directly elected. Neither were they usually empowered to vote on their own decision. Referrals back to the provincial estates for a decision on how to vote were frequent. The system only worked when a talented Councillor Pensionary or Stadtholder (Prince of Orange) was able to arrange a consensus ahead of time. Meetings were held around a large conference table in the Binnenhof (the former palace of the counts of Holland), in The Hague, which was a central location and allowed easy travel back and forth to the other provinces. Since the States of Holland met in the same palace, communication between them and their delegates to the States-General was frequent, thus increasing their influence. Each province served as presiding officer of the States-General in turn. Given this weak executive structure, and the necessity to refer business for detailed review, the proceedings were often dominated by the Councillor Pensionary of Holland as the representative of the largest province, as well as the most well informed and prepared official. Representatives of Holland as well as other provinces would often defer to his expertise.[1]: 40–47 · [5]: 292–293 · [2]: 67 · [3]: 113–114

The States-General conducted foreign relations, declared war and peace, administered the army and navy, and levied tariffs. In short, it exclusively concerned itself with all those affairs that concerned the outward and common concerns of the Republic. It had negligible power internally, which was jealously guarded by the provincial States.[3]: 110 · [2]: 67 · [5]: 292–293

One of the most important tasks of the States-General was the appointment of the commander of the Republic's armies, the Captain General of the Union. The appointment was for life. William the Silent acted as chief commander of the army as the most eminent person and the leader of the rebellion, but this was never formalised. His son, Maurice was appointed Captain-General as a counterpose to Leicester. The Dutch were fortunate in this in that Maurice turned out to be a military genius and the foremost commander of his age. After that, it was a matter of course for the incumbent Prince of Orange to be appointed Captain General. The ability of the Princes to deliver victory and protect the Republic from its enemies lead to much of their political power and ability to provide clear, effective centralised leadership. The failure of the latter Princes, William IV and William V, to live up to this heritage consequently led to a large diminution of their power internally.[3]: 131–134 · [2]: 76–82 · [5]: 293–294

Treasury

Once the budget for the year was set (as might be expected a subject of much negotiation), the percentage to be paid into the treasury of the Generality was set by tradition. As the largest, most populous, and richest province, Holland paid 58.3% of the required budget. The ability to provide this proportion of the Generality's funds is what gave the States of Holland (and as will be seen below the city of Amsterdam and its ruling burghers) their preponderance in the government. Zeeland contributed 10% to the budget, Friesland 11.7%, Utrecht 5.8%, Gelderland 3.6%, and Overijssel and Groningen 3.5% each. The poorer and more landward provinces were accessed less.[3]: 118–119 · [5]: 286–291 It might seem that Holland was over-taxed. However, when the distribution of the population (1/5), commerce, productive farmland is considered Holland was probably under-taxed.[5]: 287

The treasury of the Generality was administered by an official appointed by the States-General, the Treasurer-General. He chaired the Treasury Chamber of the Generality (Rekenkamer) and kept its books.[3]: 120 There was also a Receiver-General, who collected the taxes as well as the contributions of the member provinces. One of the key problems in this is that the Receiver-General had no authority to enforce payment into the treasury, and some of the poorer provinces were frequently in arrears.[1] · [3]: 120

The Lands of the Generality

The Generality Lands, mostly North Brabant and States-Flanders, which amounted to twenty percent of the new Republic's territory, were not assigned to any provincial council and had been conquered since 1581 from the Spanish. It was under the direct rule of the Generality, and not allowed to send representatives to the States-General. As such, these territories had no vote in the States-General.[5]: 297–300

Council of State

The Council of State (Raad van State) of the Generality functioned as the executive committee of the Union, and carried out its executive functions. It was descended from the Councils of States formed by the Burgundian Dukes and the Habsburgs. This incarnation was formed when Leicester became governor-general. After his departure, it was made subordinate to the States-General, and functioned as a subcommittee of it. It formulated the budget, organised and financed the army and navy (although naval policy was set by the Council of the Admiralty, as below), and levied taxes throughout the Union. It consisted of twelve members, appointed by the provinces for two, three, or four years, depending on the province, as well as the Prince of Orange. These members also tended to be the provinces' representatives to the States-General, as the council was a subordinate to it. The councillors, contrary to general practice, voted individually, not by province. Each councillor presided in turn.[3]: 117–120 · [5]: 293–294 Its members were fixed by tradition to:

- The Prince of Orange as Captain-General of the Union's Army and Admiral-General of the Navy.

- Gelderland - 2 councillors

- Holland - 3 councillors, one of which was the Councillor Pensionary of Holland.

- Zeeland - 2 councillors

- Utrecht - 2 councillors

- Friesland - 1 councillor

- Overijssel - 1 councillor

- Groningen - 1 councillor[1] · [3]: 117

Admiralties

The administration of the navy of the Union and supervision of all its naval affairs was centred in another committee of the States-General, the Council of the Admiralty. It was responsible for setting naval policy and budget.[3]: 121 · [2]: 69 Members were appointed by the States-General and consisted of:

- The Prince of Orange as Admiral-General of the Union (again, a lifetime employment).

- The Lieutenant Admiral-General of the Union - this was second only to the Admiral-General, and was the effective operational commander of the Navy He was most important when there was no Admiral-General/Prince of Orange appointed. Michael de Ruyter served as Lt. Admiral in his time.

- The Councillor-Pensionary of Holland, whose influence here was greater than in the army, and paramount when there was no Prince of Orange. Johan de Witt effectively commanded the navy through this position.

- others as appointed

For day-to-day administration of the navy, there were originally three different subordinate Admiralties: The Admiralty of Rotterdam, representing Holland's southern quarter, the Admiralty of Amsterdam, representing its northern quarter (1587), and the Admiralty of Zeeland, based in Middelburg. A separate Admiralty of the Noorderkwartier based in Hoorn and Enkhuizen was later established. In 1597, the States of Friesland established the Admiralty of Friesland, based in Harlingen. On 14 June 1597 the States-General, approved a proposal in which the foundation of a Generaliteitscollege was decided upon; this replaced an earlier navy board, the Collegie Superintendent, of which Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange (Admiral-General since 1588) had been the head, but which had been dissolved in 1593 as a result of disputes between the provinces. The Generaliteitscollege was to be a loose cooperation between five autonomous Admiralties to be represented in it. Each admiralty also had its own hierarchy. However, most ships and money came from Amsterdam, and after that Rotterdam and Zeeland. The situation tended to lead to divided command in battle and duplication of efforts, which could only be resolved by a strong Prince of Orange or Councillor Pensionary.[2]: 69–70 · [5]: 295–296 · [3]: 121–125

Stadtholderate

The term stadtholder is literally one who holds the state/lieutenant. One common confusion is that the office of the stadtholder was a national one. It was not; the office of Stadtholder was appointed by each of the States individually.[2]: 76 · [5]: 300–306 · [3]: 131–133 The stadtholder had been appointed by the sovereign (the Dukes of Burgundy or the Habsburgs) in each province as his representative as they were sovereign of each province separately, although traditionally Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht had the same Stadholder. By having 3, the Habsburgs prevented any one from becoming too powerful.[5]: 300–301 In the absence of the sovereign, the provincial estates appointed their stadtholder.[2]: 76 · [5]: 301 The term of office was for life. While it was held by the incumbent Prince of Orange, it was not made hereditary until the time of William IV.[2]: 76 · [5]: 302 However, the Prince of Orange was not just another appointed servant of each of the provincial States, as the Councillor Pensionary was, nor not just another noble among equals in the Netherlands. First, he was the traditional leader of the nation in war and in rebellion against Spain as the direct descendant of William the Silent, the "Father of the Fatherland". He was uniquely able to transcend the local issues of the cities, towns and provinces. As the Prince of Orange, he was also a sovereign ruler in his own right. This gave him a great deal of prestige, even in a republic. He was the center of a real court like the Stuarts and Bourbons, French speaking, and extravagant to a scale. It was natural for foreign ambassadors and dignitaries to present themselves to him and consult with him as well as to the States General to which they were officially credited. The marriage policy of the princes, allying themselves twice with the Royal Stuarts, also gave them acceptance into the royal caste of rulers. The leaders in the individual provinces as well as the States-General looked to him for leadership and guidance. A strong Prince of Orange (those of the 17th century) could make the institutions of the Republic work efficiently. A weak Prince of Orange (those of the 18th century) would contribute greatly to the weakness of the government and the Republic.[2]: 76–77, 82–83

Charted companies

The Dutch East India Company and the Dutch West India Company, as quasi governmental organisations, were also under its general supervision along with the provincial and city boards of governors of the corporations.[2]: 69–71 Staten Island in New York City (originally New Amsterdam) and Staten Island, Argentina (Discovered by Dutchman Jacob le Maire), are among places named after the Staten-Generaal.

Government of Holland

States of Holland

.jpg.webp)

The province of Holland was governed from the earliest times by the States of Holland and West Friesland. This was an assembly of all the commons and nobles (though not clerics as in other countries) to the sovereign, the count of Holland.[3]: 106 They also met in The Hague at the Binnenhof. The fact that their center of political power was also the de facto political center of the Republic gave them an advantage of the other provinces in addition to the 58.3% of the country's budget they paid. In 1653, Johan De Witt formalised their title as "their Noble Great Mightinesses, the Lords States of the Province of Holland and West Friesland". The fact that it was more laudatory than that of the States-General was meant to symbolise the supremacy of provincial sovereignty and showed where the real power lay.[1]: 57

The States of Holland met four times per year, in February, June, September, and November.[3]: 106 Each city and town represented in the States had one vote, along with the College of the nobility of Holland (Ridderschap in Dutch), which also had one vote, but voted and spoke first. Each town could send as many representatives as it deemed necessary. The delegates were chosen by the Vroedschap (see below) of the towns,[3]: 102 out of the magistrates and vroedeschappen of the town.[3]: 105 This commonly meant that one of the burgomasters and the pensioner were chosen as deputies.[3]: 128 The number of towns with voting privileges was originally six. Dordrecht was the first in rank, its pensionary acting as Councillor Pensionary if necessary. The others were Delft, Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Haarlem and Leiden. In 1572, the number of voting towns was increased to eighteen by William the Silent in light of the population growth. The additional towns were Alkmaar, Den Briel, Edam, Enkhuizen, Gorinchem, Gouda, Hoorn, Medemblik, Monnickendam, Purmerend, Schiedam, and Schoonhoven. This composition remained unchanged until the end of the Republic.[3]: 103 · [2]: 64 · [5]: 278

The same method was used to raise revenue as was used by the States-General. Each city was charged its portion. This was over and above provincial taxes on consumption, imports and exports. Amsterdam paid almost 50% of the revenues/budget of Holland. Given Holland's contribution to the Generality's budget (above), Amsterdam paid approximately 25% of the entire national budget alone. This is part of what gave that city its preponderance in national and provincial affairs.[1] · [5]: 285–291 It might appear that Holland was overtaxed compared to the rest of the provinces. However, when the distribution of the population is considered along with the fact that Holland possessed the bulk of the Republic's commerce, trade, banking, and fertile land, she may have been undertaxed (see the tax reform passed by the States General in 1792.).[5]: 287

The nobility was not very numerous in Holland, as Holland had never been very heavily feudalised. However, it still had a certain measure of prestige in an aristocratic age. They also had many prerequisites by tradition, such as the right to be appointed to certain lucrative posts and sinecures. Their hall, the Ridderzaal, was at the center of the Binnenhof. The nobility usually elected eight or nine of their number as representatives to the States and sat as the Ridderschap (college of the nobility of Holland).[3]: 104 They chaired the meetings of the States, as represented by their Pensionary, who was also counselor (retained legal advisor) to the States as a whole, hence the name Councilor Pensionary or raadpensionaris in Dutch.[3]: 105 This gave the Councillor Pensionary some of his power as he chaired the meetings of the States and spoke first as the representative of the nobility, as well as last in summing up the debates.[5]: 279 He was also the only representative with a fixed term (three years, extended to five years by the time of De Witt), an office, and the staff to prepare and study issues. The office of Chief Noble of Holland was an especially lucrative sinecure, although he was appointed by the States. Some of its holders were Louis of Nassau, Lord of De Lek and Beverweerd and Joan Wolfert van Brederode.[1]: 138–139

The two most influential delegations were the ridderschap and Amsterdam, with the rest of the delegations falling in behind them. The ridderschap came first in precedence and spoke first in debate and then voted. This was done for them by their Pensionary (the Land's Advocate, later the Councillor Pensionary). Then the other delegations declared their position, and voted in strict order of seniority: Dordrecht, then Haarlem, Delft, Leiden and Amsterdam, followed by the rest of the towns. This order was adhered to also in seating. No interruptions were allowed. The votes themselves were given on instructions from the town governments, so there was frequent consultation between the delegations and their principals in the vroedeschap. Important issues were thus widely debated and consensus reached.[5]: 279

Delegated Councillors and the Revolution of Government

Before 1572, the States of Holland, like the other provincial assemblies, were an occasional advisory body. They met when summoned by the ruler or their stadholder, almost exclusively to discuss taxes. Other topics including religion, military affairs, and foreign trade (unless related to the key Baltic and North Sea trade for Holland) were out of bounds. Between 1572 and 1576, William the Silent was at the center of decision making as stadholder. However, he consulted extensively with the States of Holland. After 1576, the States' role increased, but remained shared with William the Silent. After Leicester's departure, the sovereignty, in the absence of a sovereign or their representative, lay on the ground. The States picked it up.[5]: 277–278 ;[8]: 242–243

To accomplish this, the States under Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, instead of numerous short meetings, met for four long sessions per year, or more frequently if deemed necessary.[9] They increased the members of the assembly from the original six large cities (Dordrecht, Haarlem, Delft, Leiden, Gouda, and Amsterdam) plus the ridderschap to represent the countryside to fourteen, granting voting rights to Rotterdam, Alkmaar, Enkhuizen, Hoorn, Schoonhoven, Gorcum, Brill and Schiedam. By the 1590s this had increased to eighteen, adding Edam, Purmerend, Medemblik, and Monnickendam. From time to time other towns were invited, including Oudewater, Woerden, Naarden, Heusden, and Geertruidenberg.

A major institutional change from previous practice was introduced in 1585 when the main executive functions of Holland started to be carried out by the Gecommitteerde Raden, usually translated as "Delegated Councillors". They formed a Council of State for Holland.[3]: 106 Except in emergencies, again after 1585, the States usually could only discuss agenda items set before it by the Gecommitteerde Raden.[5]: 278 They formed a permanent standing committee of the States to carry out executive functions, with delegates from and representative of the different sized towns and constituencies in Holland:[3]: 106 ;[8]: 145

- The nobility - 1 delegate, represented by the Councilor Pensionary

- Amsterdam - 1 delegate

- Dordrecht - 1 delegate

- Rotterdam - 1 delegate

- Haarlem - 1 delegate

- Leiden - 1 delegate

- Delft - 1 delegate

- Gouda - 1 delegate

- 1 delegate from three of the smaller towns (i.e. the ones not mentioned above), each of the three choosing him by turns.

The Councilor Pensionary exercised much of influence here as he was again, the only representative with a fixed term, an office, and the staff to prepare and study issues, and then to carry them out.[1]: 138–139, 141

Critical to the success of the Delegated Councillors as an executive was the active participation of the town councils and the ridderschap. The States thus became a gathering of the towns' delegates, the town councils and the ridderschap who actively participated in the provincial government and embodied the whole province.[5]: 278–279

Delegation to the States-General

The States of Holland usually sent the following delegates to States General:[3]: 113

- 1 noble – perpetual

- 2 out of the eight chief/original towns

- 1 out of the towns of North Holland

- 2 from the provincial delegated councillors

- the Councillor Pensionary of Holland

Councilor Pensionary (formerly Land's Advocate)

%252C_Grand_Pensionary_of_Holland%252C_by_Studio_of_Adriaen_Hanneman.jpg.webp)

History

A pensionary (pensionaris in Dutch), (because of the regular payments he was a pensionarius in mediaeval Latin) was the leading functionary and legal adviser of the principal town corporations in the Low Countries because they received a salary or pension.[10] · [11] The office originated in the County of Flanders. Initially, the role was referred to as clerk or advocate. The earliest pensionaries in the County of Holland were those of Dordrecht (1468) and of Haarlem (1478). The pensionary conducted the town's legal business and was the secretary of the town council and its representative and spokesman at the meetings of the provincial States. The post of pensionary was permanent, and that permanence gave him great influence.

In the States of the province of Holland, the pensionary of the order of nobles (Ridderschap) and councilor to the States was the foremost official of that assembly. The office started in the early 14th century and ended in 1619. It was named Land's Advocate, or more shortly the Advocate (landsadvocaat). Its importance was much increased after the revolt in 1572, and still more so during the long period 1586–1619 after the death of William the Silent, when Johan van Oldenbarnevelt held the office. Many of the executive functions exercised by the sovereign and their deputies, the stadholders, devolved to the States, and were carried out by the Land's Advocate on their behalf. The office of Land's Advocate was abolished in 1619 in response to the crisis of that year between the States of Holland, as represented by Johan van Oldenbarnevelt and the stadtholder, Maurice, Prince of Orange, which the States lost.[12] Another office with more restricted powers and tenable for five years only was erected in its place with the title of Raad-Pensionaris (usually translated into English as Councilor Pensionary). He was a council member, a raad, but also pensionaris of the Nobility. He was, therefore, Raedt ende Pensionaris in seventeenth-century Dutch, which later was simplified to raadpensionaris or raadspensionaris. French diplomats referred to the raadpensionaris of Holland as the Grand-pensionnaire, i.e. the most important pensionary, to discern him from comparable officials in Dutch provinces of lesser importance. This embellishment was not used by the Dutch themselves. In English, the French term was translated as "Grand Pensionary".[3]: 105

The Estates of the province of Zeeland also had a raadpensionaris. The provinces of Groningen and Gelderland had a simple pensionaris. The provinces of Utrecht and Friesland had a landsadvocaat.

The first holders of this office were Anthony Duyck, Jacob Cats and Adrian Pauw, in the days of the stadtholders Frederick Henry and William II.

Responsibilities

That office of Councilor Pensionary's primary function was to be leader-servant of the States.[1]: 137 It shared many of the functions with the former office of Land's Advocate: chairing meetings of the States of Holland, acting in committee for them, preparing business and agendas, acting a speaker for the nobility, and acting as their legal counselor and head of bureaucracy. The councilor pensionary of Holland, in fulfilment of his pensionary function, sat with the nobles, and delivered their voice for them as well as their vote. He also assisted in their deliberations before they came to the assembly of the States. For the States of Holland as a whole, in fulfilment of his councilor function, the councilor pensionary is properly a servant or minister of the province. His place was generally last in precedence. However, he is always looked to by the States to study, organize, manage, and administer the business of the States of the province and their sub-bodies. This is because of this long tenure (originally for life, then five years and frequently re-elected), his attendance on all the committees and assemblies of importance of the province, his possession of a staff with a budget that could formulate their business (resolutions, correspondence, etc.) and then to carry out the execution of the policies the States had decided on. He was also one of the States' perpetual deputies the States-General.[3]: 104–105 From his accretion of influence and his ability to sense and influence the majority of the States' deputies, the Councilor Pensionary became by default the main executive official of the States of Holland and the States General.

The Councillor Pensionary was not the leader (i.e. proto-prime-minister), but as the pensionary of the nobility and the counselor of the States, a powerful Councillor Pensionary such as Johan de Witt could shape the agenda, its outcome, and use his influence to persuade the other members of the States (who were part-time delegates from their towns) to vote for a particular policy, and then carry it out. The same carried through to the States-General, especially as he tended to be the face of the most powerful province, Holland. As he was tasked with carrying out decisions, it was natural for other bodies, both domestic and foreign (i.e. ambassadors) to meet with him and deal with him to get the States and States-General to act on an issue.[13] "The central fact about De Witt's leadership was that he was a servant who guided his masters; he had no right of command, only the duty of persuasion.".[1]: 141 In a complex government with so much consultation, the leadership of a capable councilor pensionary such as De Witt was an essential part of the mechanism of the state.[1]: 136

While the office had fewer powers than the old office of Land's Advocate, in the First Stadtholderless Period (1650–1672) the grand pensionary became even more influential than Oldenbarneveldt himself, since there was no prince of Orange filling the offices of stadtholder as a counterbalance. From 1653 to 1672 Johan de Witt, re-elected twice, made the name of grand pensionary of Holland famous at the height of the Republic's influence.

As mentioned in the last section, most of the other provinces (except Friesland, whose government differed significantly)[3]: 137 had their own pensionary. However, none of them had the ability to build up the power and influence of that of Holland, and exercise the weight equal to Holland's influence in the Generality.

Stadtholder

The office of Stadtholder (stadhouder in Dutch), was a continuation of the Burgundian institution. Stadtholders in the Middle Ages were appointed by feudal lords to represent them in their absence. Each of the provinces of the Burgundian Netherlands had their own Stadtholder, although a Stadtholder might exercise authority over more than one province (e.g. William the Silent was Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht). A stadtholder was thus more powerful than a mere governor, who had only limited authority. In the 15th century the Dukes of Burgundy acquired most of the Low Countries, and these Burgundian Netherlands were in turn mostly governed by their own stadtholder.[2]: 76 In the 16th century, the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, also King of Spain, who had inherited the Burgundian Netherlands, continued this tradition as he had much wider interests in Spain, Germany and Italy. Stadtholders continued to be appointed to represent Philip II, his son and successor in Spain and the Low Countries. Due to the centralist and absolutist policies of Philip, the actual power of the stadtholders strongly diminished. This was one of the causes of the Dutch Revolt.[6]: 377–386 : Vol 3, Chp IV

When, in 1581, during the Dutch Revolt, most of the Dutch provinces declared their independence with the Act of Abjuration, the representative function of the stadtholder became obsolete in the rebellious northern Netherlands – the feudal lordship itself becoming vacant – but the office nevertheless continued in these provinces which now united themselves into the Dutch Republic. These United Provinces were struggling to adapt existing feudal concepts and institutions to the new situation and tended to be conservative in this matter, as they had after all rebelled against the king to defend their ancient rights. The fact that the stadtholder was William the Silent, the effective leader of the revolt, made the States determined to retain him and normalise his position.[3]: 132 The stadtholder no longer represented the lord, the States retaining the sovereignty for themselves. He was appointed by the States of each province for that province, thus making it a provincial office. However, although each province could assign its own stadtholder, in practice the Prince of Orange, the direct descendant of William the Silent, was always appointed to the Stadtholderate of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, and Guelders, and the Count/later Prince of Nassau-Dietz, a cadet branch, was appointed Stadtholder of Friesland. Groningen and Overijssel appointed one or the other prince as their stadtholder.[2]: 76

The stadtholdership of Holland and Zealand has always been combined. Since the office was instituted there in 1528, the stadtholder of Utrecht has been the same as the one of Holland, with one exception. In 1572, William of Orange was elected as the stadtholder, although Philip II had appointed a different one.[3]: 109

The highest executive power was exerted by the sovereign States of each province, but the stadtholder had some prerogatives, such as appointing of lower officials and at times the ancient right to affirm the appointment (by co-option) of the members of regent councils or choose burgomasters from a shortlist of candidates. As these councils themselves appointed most members of the States, the stadtholder could very indirectly influence the general policy over the course of time.[3]: 132–133 In Zeeland the Princes of Orange, who after the Dutch Revolt most often held the office of stadtholder there, held the dignity of First Noble, and were as such a member of the States of that province, thanks to the fact that they held the title of Marquis of Veere and Flushing as one of their patrimonial titles. Although the institutions of the Dutch Republic became more republican and entrenched as time went on, William the Silent had been offered the countship of Holland and Zeeland, and only his assassination prevented his accession to those offices. This fact did not go unforgotten by his successors.[7]: 28–31

In times of war, the stadtholder, since the Prince of Orange was also appointed Captain-General (see above) and thus commanded the army, had much more influence and thus would have more power than the Councillor Pensionary. This was often why the Princes of Orange tended to favour a policy of war, against Spain or France (as was the case with Maurice and William II), rather than a policy of peace. However, this was not actually the power to command, but the power to influence, persuade the States, and have their decisions accepted as those of the States. As mentioned above, the ability of the 17th century House of Orange-Nassau Princes of Orange to influence and drive the States to a consensus led to their leadership of the Generality. The inability of the Princes of Orange of the 18th century to do so led in great part to the fall of the Dutch Republic.[7]: 28–31, 64, 71, 93, 139–141

The Prince of Orange was also not just another noble among equals in the Netherlands. First, he was the traditional leader of the nation in war and in rebellion against Spain. He was uniquely able to transcend the local issues of the cities, towns and provinces.[3]: 133–134 He was also a sovereign ruler in his own right (see Prince of Orange article). This gave him a great deal of prestige, even in a republic. He was the center of a real court like the Stuarts and Bourbons, French-speaking, and extravagant to a scale. It was natural for foreign ambassadors and dignitaries to present themselves to him and consult with him as well as to the States General to which they were officially credited. The marriage policy of the princes, allying themselves twice with the Stuarts, also gave them acceptance into the royal caste of rulers.[2]: 76–77, 80

The States of Holland, under De Witt, tried twice to exclude the Prince of Orange from office. The first time was in 1654 as a secret annex in the Treaty of Westminster (1654) between the States of Holland and Oliver Cromwell to end the First Anglo-Dutch War; Act of Seclusion/Exclusion. Arguably, this policy, though forced on the States by Cromwell out of fear of aid to the exiled Stuarts served the interests of the States.[5]: 722–726 · .[1]: 216–235 The second time was the Perpetual Edict (1667)/Eternal Edit. The States of Holland passed it on 5 August 1667. The act abolished the office of Stadtholder in the province of Holland. At approximately the same time, a majority of provinces in the States General of the Netherlands agreed to declare the office of stadtholder (in any of the provinces) incompatible with the office of Captain general of the Dutch Republic.[5]: 791–795 · .[1]: 678–691 Both these laws fell in the Rampjaar, 1672. Prince William III was swept back into all his offices by popular demand during the events of the Franco-Dutch War.

Government of the other provinces

.jpg.webp)

The governments of the remaining provinces, except for Friesland, tended to follow the pattern of Holland with some local variations.

The form of government of Zeeland was almost identical to that of Holland. It had six representative cities: Middelburg, Vlissingen, Ter Veere, Zierikzee, Goes and Tholen. William the Silent had bought the Marquisate of Veere and Flushing in 1582, giving him the right to appoint the government (regents) in the first three cities, and making him First Noble (actually the only noble) in the province.[3]: 136–137 He thus controlled four of the seven votes, and thus the province. William the Silent had been promised the countship of Holland and Zeeland before his death. This was not granted to his heirs. However, this was another version of it, writ small, and a thorn in the side of the regents of Holland from that day to the end of the Republic.[5]: pp.280–281 · [7]: pp.29–30 · [14]

Utrecht had a States consisting of the cities of Utrecht, Amersfort, Montfoort, Rhenen and Wijk, as well as the Clergy, as the province had been governed by its bishop in the Middle Ages.[3]: 137 · [5]: pp.282

Guelders' States included delegates from Arnhem, Den Bommel, Doesburg, Elburg, Groenlo, Hardewijk, Hattern, Lochem, Nijmegen, and the Nobility, which was very numerous there.[3]: 137 · [5]: pp.282–283

Groningen functioned as a city-state based on the city of Groningen. All representation flowed through there.[3]: 140

Overijssel had a States consisting of three representative towns, Deventer, Kampen, and Zwolle, as well as the Nobility.[3]: 133–134

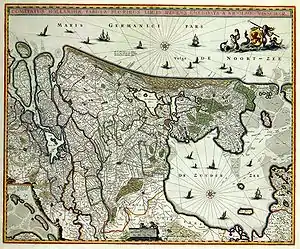

The form of government of Friesland, as mentioned above, differed from that of the other provinces. The province had its own language, Frisian, more akin to old English than to Dutch. Its government was based on universal male suffrage and had a large dose of democracy surviving from the Dark Ages. It was organised into four quarters, three of which were further divided into local subdivisions known as grietenijen and governed by a grietman. Eastergoa was divided into eleven grietenijen, Westergoa was divided into nine grietenijen, and Zevenwouden was divided into ten grietenijen. The fourth quarter consisted of the eleven towns of Friesland, of which Leeuwarden was the largest, functioning as the seat of the States of Friesland. Each grietenij and each town sent two delegates to the States. Unlike the rest of the Generality, these delegates did not need to recourse to those who elected them to make a decision on how to vote.[3]: 137–140 · [5]: pp.281–282

Arms of Voting Provinces:

Arms of the Province of Holland and West Friesland.

Arms of the Province of Holland and West Friesland. Arms of the Province of Zeeland.

Arms of the Province of Zeeland. Arms of the Province of Gelderland.

Arms of the Province of Gelderland. Arms of the Province of Utrecht.

Arms of the Province of Utrecht. Arms of the Province of Friesland.

Arms of the Province of Friesland. Arms of the Province of Groningen.

Arms of the Province of Groningen. Arms of the Province of Overijssel.

Arms of the Province of Overijssel.

Arms of Non-Voting Provinces:

Arms of Drenthe (it was not a province and had no representation in the states General).

Arms of Drenthe (it was not a province and had no representation in the states General). Arms of North Brabant (the lands of the Generality). It was governed by the States General as conquered territory and had no representation in the States General.

Arms of North Brabant (the lands of the Generality). It was governed by the States General as conquered territory and had no representation in the States General. Arms of States Flanders: the part of the county of Flanders conquered by the armies of the Republic and administered as part of Zeeland.

Arms of States Flanders: the part of the county of Flanders conquered by the armies of the Republic and administered as part of Zeeland.

Government of the cities and towns

.svg.png.webp)

Just as the delegates to the States-General of the Generality could not make any decisions without consulting back with their principals at the States of the provinces, so the delegates to the states of the provinces could not make major decisions without consulting back with their principals in the various cities and towns. As noted above, this lack of delegation of sovereignty led to a fair degree of inertia and would have been unworkable in a larger country less well connected with transport (albeit waterborne canals and shipping) links. It did, however, give the cities and towns a large amount of freedom. Also, the sovereignty of the provincial states was in practice dependent for its exercise on the magistrates of the cities. It did have the effect of issues being discussed widely and frequently so a consensus could be found by a skilled political leader, either the councillor pensionary and/or the stadholder.[2]: 71 · [3]: 107–108 · [1]: 133–136

Each of the towns and cities in the seven provinces had its own differences and peculiarities. However, as a general rule, the government of the city of Amsterdam was fairly standard, and certainly the most important.[3]: 93 Also, as noted above, in the 17th and 18th century, the wealth that Amsterdam generated from commerce made it the most powerful city in the province of Holland, accounting for half of Holland's revenues and taxes and through that a full quarter of the Generality's. Because of this economic weight, it was the most influential voice in the councils of the province and the Generality.[1] : 30–38 · [3]: 93, 99–102 ·

The government of the city was from a very early time in the hands of four Burgomasters (Burgemeesters in Dutch, but better translated to English as "mayors"), largely for the same reason that Rome had two consuls: deconcentration of power. Originally, the burgomasters were appointed by the lord or the province, the Count of Holland and their successors, the Duke of Burgundy. As the Burgundian Dukes tended to have national interests to occupy them, the appointments were often left to their stadtholders. From the 15th century on, however, their election was by a complex system. An electoral college was formed yearly, made up of the outgoing burgomasters, the alderman (City Councilmen), and all those who in the past had held the post of burgomaster or alderman. The burgomasters are chosen by simple majority. In the second stage of the election, the three newly elected burgomasters "co-opted" (chose) one of the outgoing four to stay on for a second one-year term. This way, one of the burgomasters stayed in office two years to provide continuity.[2] · [3]: 95 · [5]: 278–279, 287

The three newly chosen were called "Reigning-Burgomasters" for that year. For the first three months after a new election, the Burgomaster of the year before presides. After that time, it was supposed the new ones had learned the "Forms and Duties of their Office", and acquainted with the state of the city's affairs, so the three new burgomasters had the privilege to preside by turns.[3]: 96

College van burgemeester en wethouders.

The burgomasters functioned as the executive of the city government. They were in command of the civic guard (the famous militia companies of the Dutch paintings) and troops stationed in the city. They appointed the city functionaries such as the administrators in charge of the welfare of orphans and of vacant succession, charitable institutions, and the captains of the companies of the civic guard. issue out all Monies out of the common Stock or Treasure, judging alone what is necessary for the Safety, Convenience, or Dignity of the City. They also kept the Key of the Bank of Amsterdam, which at the time functioned as one of the central banks of the nations of Europe. The vaults were never opened without one of them present. They were also in charge of all the public works of the city, such as the ramparts, public buildings (for example the great Amsterdam City Hall, now a Royal Palace).[3]: 96

The salary of a Burgomaster of Amsterdam was 500 guilders a year, though there are offices worth ten times as much at their disposal. None of them was known to have taken bribes: a credit to the integrity of the system.[3]: 96

Most cities, Amsterdam being no exception, employed a pensionary. He was the leading functionary and legal adviser of the principal town corporations in the Netherlands. They received a salary, or pension, hence the name. The office originated in Flanders, and was originally known by the name of clerk or advocate. The earliest pensionaries in Holland were those of Dordrecht (1468) and of Haarlem (1478). The pensionary conducted the legal business of the town, and was the secretary of the city council. He was also one of the city's representatives and spokesman at the meetings of the provincial States. The post of pensionary was permanent. As the official who kept a large part of the town's business in his hands, and had the most knowledge and experience, his influence was as great on the city level as the corresponding office, the Councillor Pensionary of Holland, was at the provincial and national level. Johan de Witt was originally pensionary of Dordrecht before he was appointed Councillor Pensionary of Holland.[3]: 99–100

The official responsible for the administration of justice was the schout. In former times he was the representative of the count of Holland. During the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, he was appointed by the burgomasters. In other towns and cities in Holland, this appointment was the prerogative of the States of Holland. The schout was the chief of police and the public prosecutor ("district attorney" in the US, Crown Prosecutor in the UK). The schout, through the colony of New Netherland (the present New York and New Jersey), is the origin of the American institution of district attorney and attorney general.[15] · [3]: 98

The schout also functioned as president of the Tribunal of Aldermen (Schepen), which sat as judges in the cases brought before it by the schout. They were the court of last appeal in criminal cases. They did not pass a death sentence without first advising the burgomasters of the possibility of that decision. Other than that, the burgomasters had no role in the process. In civil cases, after a certain value, there was a right of appeal to the Court of Justice of the province in The Hague. The Tribunal consisted of nine aldermen. The schepen were chosen annually by the stadtholder from a list of fourteen presented to him by the Vroedschap. In the absence of a stadtholder, as in 1650–72 and 1702–48, the aldermen were chosen by the burgomasters. Seven are chosen annually, two from the previous year continued in office. The list is compiled by the Vroedschap.[3]: 97–98

The Vroedschap, or city council (the modern equivalent in The Netherlands is the Municipal council) was really a Senate in the ancient Roman republican sense. As a fourth branch of the city government, it was a direct backup to the power of the burgomasters. It was a college of 36 members, "men both rich and wise" whose task was to "counsel" the burgomasters. Its members were called vroedman, literally a "wise man". An honorific title of the vroedschap was the vroede vaderen, or the "wise fathers". This practice was reminiscent of the ancient Roman Senate, the modern word senate being derived from the Latin word senātus (senate), which comes from senex, "old man". The influence of the Vroedschap on the city government had its precedence again in that of the Roman Senate.[3]: 93–95

In the past, election to the Vroedschap had been by majority of citizens gathered in a large assembly, usually at a large church, upon the death of a member, by a majority of the voices present.[3]: 94 This practice was discontinued in favour of the co-option system around the year 1500, when the towns became too large to assemble the people in one place without tumult.[3]: 94 By resolution of the burghers, vacancies to the Vroedschap were filled by co-option from that time forward, i.e. by vote of the members of the Vroedschap. Members were elected for life. As the members of the city government who were burgomasters, aldermen, and other city officials were chosen for the Vroedschap, and the vroedemen tended to choose each other for these offices without intervention from the burghers, city governments developed an oligarchy.[2]: 65–74 [3]: 95

The members of the four colleges above that constituted the city government were dominated by a relatively small group of rich merchant, financial or land-owning families, many closely interrelated, called the "regents", or regenten. A list of them can be found here and along with some that were later ennobled, here. It was not impossible to gain access, by success in business and being co-opted into the Vroedschap and the other colleges. This was most likely to happen when the stadtholder at that time appointed a new person into one of the colleges by choosing from the lists presented to him or making his own choice (the latter was called "changing the government").[5]: 305 The system was not immune to popular pressure, as events of the age showed, but it became tighter and more closed as time went on until the Republic fell. A son of family belonging to the regent class there opened up an equivalent of the Roman cursus honorum where he could show his talents and make the connections that would serve him and his city. As these same officials were appointed to provincial offices (e.g. delegate to the States of Holland, member of one of the admiralty boards) or offices under the Generality (ambassadors), the councils of local power perpetuated themselves into the regional and national levels.[2]: 72–74

First Stadtholderless period and the Great Assembly

The First Stadtholderless Period or Era (1650–72; Dutch: Eerste Stadhouderloze Tijdperk) is the period in the history of the Dutch Republic in which the office of a Stadtholder was absent in five of the seven Dutch provinces (the provinces of Friesland and Groningen, however, retained their customary stadtholder from the cadet branch of the House of Orange). It happened to coincide with the period when it reached the zenith of its economic, military and political Golden Age.

Politically, the Staatsgezinde (Republican) faction of the ruling Dutch Regents, led by such talented men as Johan de Witt, his brother Cornelis de Witt, Cornelis de Graeff, Andries de Graeff and Andries Bicker (the last three uncles of Johan de Witt's wife) dominated. It was fortunate for the Republic that capable leadership arose in the absence of a Prince of Orange. The faction even thought through an ideological justification of republicanism (the "True Freedom") that went against the contemporary European trend of monarchical absolutism, but previewed "modern" political ideas that eventually found their fullest expression in the American and French constitutions of the 18th century. There was a "monarchical" opposing undertow, however, from the adherents of the House of Orange that wanted to restore the young Prince of Orange to the position of Stadtholder that his father, grandfather, great-uncle, and great-grandfather had held. The republicans attempted to rule this out by constitutional prohibitions, like the Act of Seclusion, but were eventually unsuccessful in the crisis of the Rampjaar (Year of Disaster) of 1672, that brought about the fall of the De Witt-regime.[7][1][14]

The Gecommitteerde Raden (executive committee) of the States of Holland moved immediately to reassert their authority over the army and convened a plenary session of the States. Next Holland proposed in the States General that a so-called Great Assembly (a kind of constitutional convention) should be convened at short notice, to amend the Union of Utrecht.[5]: 702–703

The States of Holland did not wait for this Assembly, however, but for their own province immediately started to make constitutional alterations. On December 8, 1650, the States formally took over their Stadtholders' powers. The eighteen voting towns in the States were given the option to apply for a charter that enabled them to henceforth elect their own vroedschap members and magistrates, under ultimate supervision of the States, but otherwise without the usual drawing up of double lists, for outsiders to choose from. This did not apply to the non-voting towns, however, that still had to present double lists, but now to the States, instead of the Stadtholder. The States also assumed the power to appoint magistrates in the unincorporated countryside, like drosten and baljuws.[1]: 40–57 · [5] : 703–704

This did imply a significant change in the power structure in the province. The position of the city regents was improved, while the ridderschap (the oligarchical representative body of the nobility in the States, that had one vote, equal to one city) lost influence, especially in the countryside. The change also diminished the power of the representative bodies of the guilds in the cities, that had often acted as a check on the power of the vroedschap with the help of the stadtholder. The change therefore did not go unopposed, and caused some rioting by the groups being disenfranchised.[1][5] : 704

It was clear that the leadership of the republic was now in the hands of Holland. The other power center, the House of Orange, was out of the way, at least until William III came of age. The constitutional conflict between central authority, represented by the Princes of Orange, and provincial particularism, as represented by the States of Holland, had largely been a false one. Since the beginning of the Republic, these two institutions had largely exercised leadership in cooperation, with the two notable exceptions of Maurice and Oldenbarnevelt in 1618–19 and between William II and Holland in 1650. It had been one more of form instead of the deeper underlying one of function: who was to lead the Republic. For the present, the answer was clear. The leadership of the state and the aims of national policy would be led by the States of Holland.[1]: 47 The Great Assembly sealed the transfer of leadership to Holland alone.[1]: 56 In the institutes of the state, the new patterns soon showed themselves. The States General, where the deputies of the other provinces were so recently subservient to the Prince of Orange, now deferred to the judgment of Holland.[1]: 47

Political parties

There was a periodic power struggle between the Orangists ("Oranjegezind"), who supported the stadtholders of the House of Orange-Nassau, and the States Party ("Staatengezind"), who supported the States-General and sought to replace the semi-hereditary nature of the stadtholdership with a true republican structure. It would be a mistake to think of either of these factions as political parties in the modern sense, as they were really loosely aligned groupings of interests and families that sought power in the States. Many of the people and groupings that were part of one faction could as easily be found at later times in different factions as their interests and family alliances changed.[7]: 97–99 ;[1]: 44–45 ;[14]: 28–29

As noted above, the States Party, or Staatsgezinden developed out of the Loevestein faction of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt.[7]: 97 Behind the theological debate of the Remonstrant–Counter-Remonstrant clash lay a political one between Prince Maurice, a strong military leader, and his former mentor Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, Land's Advocate of Holland and personification of civil power. Maurice desired war with Holland's enemy, Roman Catholic Spain. War would preserve his power and influence in the State. There was also no small part of revenge against Spain for assassinating his father. Maurice also confessed he was unable to make head or tail of the theological points. However, his sympathies were clear by 1610 when the Counter-remonstrants paraded their loyalty to the House of Nassau.[5]: 433 As Maurice is purported to have said, "I know not whether predestination is green or blue, but I know the Advocate's pipe, and mine will never play the same tune.".[12]: 345 Van Oldenbarnevelt, along with Arminius and his followers, desired peace. They saw no great benefit to the continuation of war and real danger to Holland's developing trade. They also saw the sovereignty of the States of Holland as paramount. In their eyes, this meant state supremacy over the church.[7]: 46–47 [12]: 344 [5]: 438, 446 [16] Personally, many of the regents were Counter-Remonstrant minded, but the coalition suited their political interests at the time.[17]

Because of this, an influential part of the regents had never been reconciled to Maurice's treatment of their colleagues, in part because they were related to them. When William II died in 1650 with only a posthumous son, William III, the regents of Holland and the States Party stepped into the vacuum. The States Party at the height of the Republic in the First Stadholderless Period were led by such talented men as Johan de Witt, his brother Cornelis de Witt, Cornelis de Graeff, Andries de Graeff and Andries Bicker. During the Second Statholderless period, the States Party were again led by the Raadpensionaris of the time. As also noted above, the faction even thought through, at least during De Witt's time, an ideological justification of republicanism Ware Vrijheid (the "True Freedom") that went against the contemporary European trend of monarchical absolutism. De Witt and his allies primarily defended Van Oldenbarnevelt's and Grotius' claim to supremacy of (Holland's) provincial sovereignty over the sovereignty of the Generality. But the doctrine went further. "True Freedom" implied the rejection of an "eminent head", not only of the federal state (where it would have conflicted with provincial sovereignty), but also of the provincial political system. De Witt considered Princes and Potentates as such, as detrimental to the public good, because of their inherent tendency to waste tax payers' money on military adventures in search of glory and useless territorial aggrandisement. As the province of Holland only abutted friendly territory and its interests were centred on commercial activities at sea, the Holland regents had no territorial designs themselves, and they looked askance at such designs by the other provinces, because they knew they were likely to have to foot the bill.[1]: 45–49 [14]: 65

This doctrine was formalised in works by De Witt himself on economics as well as his cousin's (also John de Wit) work on the "Public Gebedt" (Public Debt). By far the most complete reasoning behind the Republican regime came from Peter de la Court. The most famous of these, "The Interest van Holland" was published in 1662 and immediately became a bestseller in Holland and later also elsewhere. The book contained an analysis of the miraculous economic success of Holland, the leading province of the Dutch Republic, and then set out to establish the economic and political principles on which that success was based. De la Court identified free competition and the republican form of government as the leading factors contributing to the wealth and power of his home country. The text of the last English edition of the Interest can be downloaded from the website of the Liberty Fund: Pieter de la Court, The True Interest and Political Maxims, of the Republic of Holland (1662).

There was a "monarchical" opposing movement, however, came from the adherents of the House of Orange, loosely grouped into the "Orangist" faction, that wanted to restore the young Prince of Orange to the position of Stadtholder that his father, grandfather, great-uncle, and great-grandfather had held. Their adherence to the Prince of Orange's dynastic interest was partly a matter of personal advancement, as many Orangist regents resented being ousted from the offices they had monopolized under the Stadtholderate. Many adherents were also relatives of the House of Orange (i.e. the House of Nassau) and minor nobles whose influence would be greater under an "eminent" head such as a Prince of Orange, who could be a prime mover in the State and the Army and thus a dispenser of patronage. It was also, for members of the lower nobility, perfectly reasonable that they should be led by the fairly royal Prince of Orange in an age when all other nations were led by Kings and Emperors.[1]: 47 [14]: 59

Many people also had a genuine ideological attachment to the "monarchical" principle. As the analogy of the Dutch Republic with the biblical People of Israel was never far from people's minds, this helped to give an important underpinning for the Orangist claims in the mind of the common people, who were greatly influenced from the pulpit. The Prince of Orange was seen in his traditional role as the leader of the nation in its independence movement, and its protector from foreign threats.[1]: 781–797 [5]: 569, 604, 608, 660, 664, 720, 785–6 References to biblical kings were never far from most of the Calvinist preacher's sermons. Other favourite metaphors were the likening of the Princes of Orange to Moses leading the people of the Netherlands out of the Spanish "house of bondage". Given the prevalence of dangers from floods, the Lord was seen as having placed the protection of the Dutch people from inundation, both physical and metaphysical religious terms in the hands of the Princes of Orange.[16]: 65–67 Of course, the conservative Calvinist Reformed Church thought its interests best served by the Stadtholder from the House of Orange who had served them in the Remonstrant–Counter-Remonstrant controversy in 1619 under Maurice of Orange that culminated in the Synod of Dort. The Erastianism of the Holland regents was seen as a constant threat to its independence and orthodoxy.[5]: 429–430

The Republicans attempted to rule out the return of the House of Orange and cement their rule by constitutional prohibitions, like the Act of Seclusion (demanded by Cromwell, but not resisted by the Republicans). They were eventually unsuccessful in the crisis of the Rampjaar (Year of Disaster) of 1672, as the majority of the people turned to the Prince of Orange, William III, in the crisis. That brought about the fall of the De Witt-regime. Similarly, in the crisis of the French invasion of 1747, the Republican regime collapsed and brought about the installation of William IV as Stadholder. During the Anglo-French War (1778–1783), the internal territory was divided into groups: the Patriots, who were pro-French and pro-American and the Orangists, who were pro-British.[18]

Influence

The framers of the U.S. Constitution were influenced by the Constitution of the Republic of the United Provinces. They took from the Dutch Republic the idea of a "sovereign union of sovereign states". They also took from the Dutch example the need for political and administrative power to be exercised and interlocked at different levels: local, regional and national. The other great example taken from the Dutch was the ability to compromise in order to achieve a goal for the common good. However, the Dutch Republic, as cited in the Federalist papers by Hamilton, provided an example to be avoided of not allowing the (Con)Federal national government sufficient power to carry out its duties, collect its revenue, and come to decisions in a timely manner as set down in law.[19]

In addition, the Act of Abjuration, essentially the declaration of independence of the United Provinces, is strikingly similar to the later American Declaration of Independence,[20] though concrete evidence that the former directly influenced the latter is absent.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Rowen, Herbert H. (1978). John de Witt, grand pensionary of Holland, 1625-1672. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691052472.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Haley, K(enneth) H(arold) D(obson) (1972). The Dutch in the Seventeenth Century. Thames and Hudson. p. 78. ISBN 0-15-518473-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 Temple, Sir William (1705) [1668], Observations upon the United Provinces of the Netherlands (7th ed.), London: Jacob Tonfon within Grays-Inn Gate next Grays-Inn Lane, and Awnfoam and John Churchill at the Black Swan in Tater-No/ler-Row*, ISBN 9780598006608

- ↑ Poelhekke, J. J. "Politieke ontwikkeling der Republic onder Frederik Hendrik to 1643" in Algemene Geschiedenis der Nederlanden. Vol. VI. Thames and Hudson. p. 241.

"How sweet it was", observed the French visitor Saint-Evrenmond, who fled royal oppression at home, "to live in a country where the laws protect us from the will of men...." (from "oeuvres de Monsieur de Saint-Evrenmond, publicées sur ses Manuscrits, 5th ed, 5 vols (Amsterdam, 1739), II, 397)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 Israel, Jonathan I. (1995). The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness and Fall, 1477-1806. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-873072-1.

- 1 2 Motley, John Lothrop (1855). The Rise of the Dutch Republic. Harper & Brothers.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Rowen, Herbert H. (1988). The princes of Orange: the stadtholders in the Dutch Republic. Cambridge University Press. p. 29. ISBN 0-8063-4811-9.

- 1 2 Parker, Geoffrey (1977). The Dutch Revolt. Penguin Books.

- ↑ jul;j

- ↑ "Pensionary". WikiDictionary. Retrieved 2022-02-02.

- ↑ Etymologiebank: pensionaris

- 1 2 3 Motley, John Lothrop (1860). History of the United Netherlands from the Death of William the Silent to the Synod of Dort. London: John Murray.

- ↑ Blok, Petrus Johannes (1898). History of the people of the Netherlands. New York: G. P. Putnam's sons.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Geyl, Pieter (2002). Orange and Stuart 1641-1672. Arnold Pomerans (trans.) (reprint ed.). Phoenix.

- ↑ Joan E. Jacoby (May–June 1997). "The American Prosecutor in Historical Context" (PDF). The Prosecutor. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- 1 2 Schama, Simon (1987). The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-51075-5.

- ↑ Rabbie, Edwin (1995). Hugo Grotius: Ordinum Hollandiae ac Westfrisiae Pietas, 1613. Brill.

- ↑ Ertl 2008, p. 217.

- ↑ Alexander Hamilton, James Madison (1787-12-11). Federalist Papers no. 20. Retrieved 2011-07-08.

- ↑ Barbara Wolff (1998-06-29). "Was Declaration of Independence inspired by Dutch?". University of Wisconsin–Madison. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

Further reading/Bibliography

- Ertl, Alan W. (2008). Toward an Understanding of Europe: A Political Economic Précis of Continental Integration. Universal-Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59942-983-0.

- John Lothrop Motley, "The Rise of the Dutch Republic". New York: Harper & Brothers, 1855.

- John Lothrop Motley, "History of the United Netherlands from the Death of William the Silent to the Synod of Dort". London: John Murray, 1860.

- Herbert H. Rowen, John de Witt, grand pensionary of Holland, 1625-1672. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1978, which is summarised in

- Herbert H. Rowen, "John de Witt: Statesman of the "True Freedom"". Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Herbert H. Rowen, The princes of Orange: the stadholders in the Dutch Republic. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Herbert H. Rowen, The princes of Orange: the stadholders in the Dutch Republic. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Petrus Johannes Blok, "History of the people of the Netherlands". New York: G. P. Putnam's sons, 1898.

- Pieter Geyl, "Orange and Stuart, 1641-1672". Scribner, 1970.

- Jonathan I. Israel, "The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall, 1477–1806" Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-19-820734-4

- Reynolds, Clark G. Navies in History. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1998

- Geoffrey Parker, The Dutch Revolt. London: Allen Lane, 1977.[1]

- Schama, Simon The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age. New York: Random House USA, 1988

- Sir William Temple: Temple, Sir William (1705) [1668]. Observations upon the United Provinces of the Netherlands (7th ed.). London: Jacob Tonfon within Grays-Inn Gate next Grays-Inn Lane, and Awnfoam and John Churchill at the Black Swan in Tater-No/ler-Row*. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

52°04′48″N 4°18′00″E / 52.08000°N 4.30000°E

- ↑ Kossmann, E. H. (January 1979). "Reviewed Work: The Dutch Revolt by Geoffrey Parker". The English Historical Review. 94 (370): 127–129. doi:10.1093/ehr/XCIV.CCCLXX.127. JSTOR 567166.