| Polymyalgia rheumatica | |

|---|---|

| |

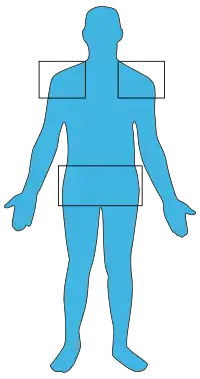

| In polmyalgia rheumatica, pain is usually located in the shoulders and hips. | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

| Symptoms | Shoulder, neck and hip pain[1] |

| Usual onset | Age greater than 50 |

| Diagnostic method | Elevated inflammatory markers, CRP and ESR |

| Differential diagnosis | Myositis, giant cell arteritis |

| Medication | Corticosteroids |

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is a syndrome experienced as pain or stiffness, usually in the neck, shoulders, upper arms, and hips, but which may occur all over the body. The pain can be sudden or can occur gradually over a period. Most people with PMR wake up in the morning with pain in their muscles; however, cases have occurred in which the person has developed the pain during the evenings or has pain and stiffness all day long.[1][2]

People who have polymyalgia rheumatica may also have temporal arteritis (giant cell arteritis), an inflammation of blood vessels in the face which can cause blindness if not treated quickly.[3] The pain and stiffness can result in a lowered quality of life, and can lead to depression.[1] It is thought to be brought on by a viral or bacterial illness or trauma of some kind, but genetics play a role as well.[4] Persons of Northern European descent are at greater risk.[4] There is no definitive laboratory test, but C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) can be useful.

PMR is usually treated with corticosteroids taken by mouth.[5] Most people need to continue the corticosteroid treatment for two to three years.[6] PMR sometimes goes away on its own in a year or two, but medications and self-care measures can improve the rate of recovery.[7]

PMR was first established as a distinct disease in 1966 by a case report[8] on 11 patients at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City.[9] It takes its name from the Greek word Πολυμυαλγία polymyalgia, which means "pain in many muscles".

Signs and symptoms

A wide range of symptoms can indicate if a person has polymyalgia rheumatica. The classic symptoms include:[10]

- Pain and stiffness (moderate to severe) in the neck, shoulders, upper arms, thighs, and hips, which inhibits activity, especially in the morning/after sleeping. Pain can also occur in the groin area and in the buttocks. The pain can be limited to one of these areas as well. It is a disease of the "girdles" meaning shoulder girdle or pelvic girdle.

- Fatigue and lack of appetite (possibly leading to weight loss)

- Anemia

- An overall feeling of illness or flu-like symptoms.

- Low-grade (mild) fever[11] or abnormal temperature is sometimes present.

- In most people, it is characterized by constant fatigue, weakness and sometimes exhaustion.

- Night sweating

- Weight loss

- Swollen hands and feet because of retained moisture

About 15% of people who are diagnosed with polymyalgia rheumatica also have temporal arteritis, and about 50% of people with temporal arteritis have polymyalgia rheumatica. Some symptoms of temporal arteritis include headaches, scalp tenderness, jaw or facial soreness, distorted vision, or aching in the limbs caused by decreased blood flow, and fatigue.[2]

Causes

The cause of PMR is not well understood. The pain and stiffness result from the activity of inflammatory cells and proteins that are normally a part of the body's disease-fighting immune system, and the inflammatory activity seems to be concentrated in tissues surrounding the affected joints.[12] During this disorder, the white blood cells in the body attack the lining of the joints, causing inflammation.[13] Inherited factors also play a role in the probability that an individual will develop PMR. Several theories have included viral stimulation of the immune system in genetically susceptible individuals.[14]

Infectious diseases may be a contributing factor. This would be expected with sudden onset of symptoms, for example. In addition, new cases often appear in cycles in the general population, implying a viral connection. Studies are inconclusive, but several somewhat common viruses were identified as possible triggers for PMR.[12] As of 2008, per a pamphlet from the Mayo Clinic the viruses thought to be involved included the adenovirus, which causes respiratory infections; the human parvovirus B19, an infection that affects children; and the human parainfluenza virus.[13] Subsequent prospective studies have shown, that there is no link between Parvovirus B19 and PM.[15]

Persons having the HLA-DR4 type of human leucocyte antigen appear to have a higher risk of PMR.[16]

Diagnosis

No specific test exists to diagnose polymyalgia rheumatica; many other diseases can cause inflammation and pain in muscles, but a few tests can help narrow down the cause of the pain. Limitation in shoulder motion or swelling of the joints in the wrists or hands, are noted by the doctor.[14] A patient's answers to questions, a general physical exam, and the results of tests can help a doctor determine the cause of pain and stiffness.[17]

One blood test usually performed is the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) which measures how fast the patient's red blood cells settle in a test tube. The faster the red blood cells settle, the higher the ESR value (measured in mm/hour), which suggests that inflammation may be present. Many conditions can cause an elevated ESR, so this test alone is not proof that a person has polymyalgia rheumatica.[17][18]

Another test that checks the level of C-reactive protein (CRP) in the blood may also be conducted. CRP is produced by the liver in response to an injury or infection, and people with polymyalgia rheumatica usually have high levels.[17][18] However, like the ESR, this test is also not very specific.

Polymyalgia rheumatica is sometimes associated with temporal arteritis, a condition requiring more aggressive therapy. To test for this additional disorder, a biopsy sample may be taken from the temporal artery.[17]

Treatment

Prednisone is the drug of choice for PMR,[19] and treatment duration is frequently greater than one year.[14] If the patient does not experience dramatic improvement after three days of 10–20 mg oral prednisone per day, the diagnosis should be reconsidered.[20] Sometimes relief of symptoms occurs in only several hours.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen are ineffective in the initial treatment of PMR,[21] but they may be used in conjunction with the maintenance dose of corticosteroid.[22]

Along with medical treatment, patients are encouraged to exercise and eat healthily, helping to maintain a strong immune system and build strong muscles and bones.[23] A diet of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat meat and dairy products, avoiding foods with high levels of refined sugars and salt is recommended.[24] Research in the UK has also suggested that people with polymyalgia rheumatica would benefit from a falls assessment when first diagnosed, and regular treatment reviews.[25][26]

Epidemiology

No circumstances are certain as to which an individual will get polymyalgia rheumatica, but a few factors show a relationship with the disorder:

- Usually, PMR only affects adults over the age of 50.[21]

- The average age of a person who has PMR is about 70 years old.[2][27]

- Women are twice as likely to get PMR as men.[27]

- Caucasians are more likely to get this disease.[2] It is more likely to affect people of Northern European origin; Scandinavians are especially vulnerable.[27]

- About 50% of people with temporal arteritis also have polymyalgia rheumatica.[2]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Polymyalgia Rheumatica". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. April 11, 2017. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gelfand JL (November 18, 2007). "Polymyalgia Rheumatica and Temporal Arteritis". WebMD. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- ↑ Schmidt J, Warrington KJ (August 1, 2011). "Polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis in older patients: diagnosis and pharmacological management". Drugs & Aging. 28 (8): 651–66. doi:10.2165/11592500-000000000-00000. PMID 21812500. S2CID 44787949.

- 1 2 Cimmino MA (1997). "Genetic and environmental factors in polymyalgia rheumatica". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 56 (10): 576–577. doi:10.1136/ard.56.10.576. PMC 1752263. PMID 9389216.

- ↑ Dejaco C, Singh YP (October 2015). "2015 Recommendations for the management of polymyalgia rheumatica: a European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology collaborative initiative". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 74 (10): 1799–807. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207492. hdl:2445/115060. PMID 26359488.

- ↑ "Polymyalgia Rheumatica treatments and drugs". MayoClinic. December 4, 2010. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Polymyalgia Rheumatica definition". MayoClinic. May 17, 2008. Archived from the original on June 23, 2008. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- ↑ Davison S, Spiera H, Plotz CM (February 1966). "Polymyalgia rheumatica". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 9 (1): 18–23. doi:10.1002/art.1780090103. PMID 4952416.

- ↑ Plotz, Charles; Docken, William (May 2013). "Letters: More on the History of Polymyalgia Rheumatica and Giant Cell Arteritis". The Rheumatologist. ACR/ARHP. Archived from the original on February 12, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Polymyalgia rheumatica". NHS. October 20, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ↑ "Polymyalgia Rheumatica symptoms". MayoClinic. December 4, 2010. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- 1 2 "Polymyalgia Rheumatica causes". MayoClinic. December 4, 2010. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- 1 2 "Polymyalgia Rheumatica causes". MayoClinic. May 17, 2008. Archived from the original on June 23, 2008. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Shiel Jr WC (March 13, 2008). "Polymyalgia Rheumatica (PMR) & Giant Cell Arteritis (Temporal Arteritis)". MedicineNet. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- ↑ Peris, Pilar (December 2003). "Polymyalgia rheumatica is not seasonal in pattern and is unrelated to parvovirus b19 infection". The Journal of Rheumatology. 30 (12): 2624–2626. ISSN 0315-162X. PMID 14719204.

- ↑ Page 255 in: Elizabeth D Agabegi; Agabegi, Steven S. (2008). Step-Up to Medicine (Step-Up Series). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-7153-5.

- 1 2 3 4 "Polymyalgia Rheumatica tests and diagnosis". MayoClinic. December 4, 2010. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- 1 2 "Polymyalgia Rheumatica tests and diagnosis". MayoClinic. May 17, 2008. Archived from the original on June 23, 2008. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- ↑ Hernández-Rodríguez J, Cid MC, López-Soto A, Espigol-Frigolé G, Bosch X (November 2009). "Treatment of polymyalgia rheumatica: a systematic review". Archives of Internal Medicine. 169 (20): 1839–50. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.352. PMID 19901135.

- ↑ McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA (2010). Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment. p. 767. ISBN 978-0071624442.

- 1 2 Docken WP (August 2009). "Polymyalgia rheumatica". American College of Rheumatology. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Polymyalgia rheumatica". MDGuidelines. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Polymyalgia Rheumatica lifestyle and home remedies". MayoClinic. May 17, 2008. Archived from the original on June 23, 2008. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Polymyalgia Rheumatica lifestyle and home remedies". MayoClinic. December 4, 2010. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Polymyalgia rheumatica: treatment reviews are needed". NIHR Evidence. June 21, 2022. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_51304. S2CID 251774691. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ↑ Singh Sokal, Balamrit; Hilder, Samantha L.; Paskins, Zoe; Mallen, Christian D; Muller, Sara (2021). "Fragility fractures and prescriptions of medications for osteoporosis in patients with polymyalgia rheumatica: results from the PMR Cohort Study". Rheumatology Advances in Practice. 5 (3): rkab094. doi:10.1093/rap/rkab094. PMC 8712242. PMID 34988356.

- 1 2 3 "Polymyalgia Rheumatica risk factors". MayoClinic. December 4, 2010. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

External links

- Questions and Answers about Polymyalgia Rheumatica and Giant Cell Arteritis - US National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

- Symptomatrix