The Portraits of Johann Sebastian Bach are various paintings in which the Baroque German composer Johann Sebastian Bach is portrayed. The Bach portrait painted by Elias Gottlob Haussmann is the best known of all and different copies of it were made over the years. Other paintings have also been discovered often with debate regarding their authenticity.

Portraits clearly identified as Bach

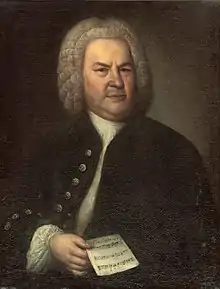

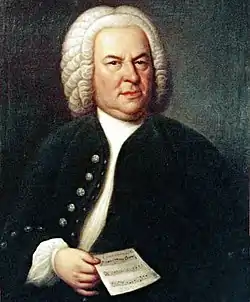

Elias Gottlob Haussmann

In 1747, Bach was admitted as the fourteenth member of the Correspondierende Societät der musicalischen Wissenschaften (lit. 'Corresponding society of musical sciences') of Lorenz Christoph Mizler, an association for musical studies founded in 1738. Under the society's rules, each member had to donate a portrait of himself to the society's headquarters. It would serve as a model for the engravings that, together with the various biographies of the members, would appear in the Musicalische Bibliothek (Musical library), the official magazine of the association.[1]

Upon joining, Bach handed in his own portrait made in 1746 by Elias Gottlob Haussmann. In it, Bach upholds the triple six-voice canon BWV 1076. The company, in fact, required candidates to submit a scientific-mathematical work as proof of his erudition.[2]

According to an oral tradition, after the dissolution of the association in 1755, the painting was donated by Mizler to Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, who, around 1800, donated or sold it to August Eberhard Müller, assistant to the Thomaskirche cantor Johann Adam Hiller and then his successor. Müller, in 1809, then donated it to the Thomasschule.[3]

Over the years, the portrait underwent various more or less drastic restorations:[3] in 1852 it was refreshed, and, in 1879, the painter Friedrich Preller the Younger repainted it heavily. In 1913 the Thomasschule gave it on permanent loan to the Municipal History Museum in Leipzig, where it underwent further restoration and where it still stands today. In 1960 it was examined by the Dresden Institut für Denkmalpflege, which confirmed the numerous operations it underwent.[4]

A 1748 copy of Haussmann's painting belonged to Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, then passing to Johann Christian Kittel. Subsequently, after the latter's death, it was purchased from an antique dealer in Berlin by the Jenke family.[5] Some argue that this is the original portrait that Bach gave to Mizler's society, and that the previous one is the replica. In this case, the dates of the two portraits should be reversed.[6]

In 1791, Johann Marcus David made a copy of the authentic portraits executed by Haussmann. It resembled the 1746 portrait in the features of the dress and the 1748 portrait in the face. As to its origin, it may have been commissioned by Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752–1814), known to have been in possession of a portrait of Bach, and, after him, the painting may have passed to Georg Pölchau. The last owner of it, Helene Brest, died in the Battle of Berlin in 1945 during the World War II, and later her painting was destroyed.[7]

Possible portraits

- Joachim Ernst Rentsch portrait was found in 1877 in an Erfurt attic and would represent the young Bach between 1708 and 1717, when he was Kapellmeister at the Weimar court. It was restored and presented by Alfred Overmann, director of the Erfurt city museum, as a possible authentic portrait.[3] However, many doubts were raised about its authenticity. Despite several unusual details of features and clothing, art historian and Bach expert Teri Noel Towe did not consider it an authentic portrait. Instead Musicologist Heinrich Besseler was sure of its authenticity, particularly because of its ophthalmological characteristics. It is currently located in the Erfurt city museum.[8]

- Bach as Cöthen Court Kapellmeister was painted by J. J. Ihle. This painting is alleged to have portrayed Bach between 1717 and 1723, during his tenure as Kapellmeister to Leopold, Prince of Anhalt-Köthen. It was discovered in 1897 by Max Hartmann in Bayreuth, in the house of a baker. After restoration, it was acquired by Oskar von Hase, director of Breitkopf & Härtel in Leipzig, and in 1907 it was donated to the Bach-Museum in Eisenach, where it is currently located.[9] Its authenticity is based only on conjectures and was strongly contested, also due to the geographical distance between the portrait painter and prince Leopold and the difficulty of reconciling the dates of possible realization (1717–1723) with the age of the artist (1702–1774).[10]

- Meinungen pastel was painted by Bach's distant cousin, Gottlieb Friedrich Bach (1714–1786).[11] During the 19th century it was inherited by members of the Meiningen branch of the Bach family. Karl Bernhard Paul Bach (1878–1968) claimed that the pastel was the work of his ancestor Friedrich Bach, son of Johann Ludwig Bach, Kapellmeister at the Meiningen court, and that it was presumably made when Friedrich Bach visited Leipzig in 1732.[12] Musicologist Besseler argues that the blue jacket is the Dresden court composer's uniform, and that the portrait can therefore be dated to around 1736-37.[13] Although Bach had brown eyes, the person portrayed on the pastel has blue eyes. This, perhaps, may indicate that the cake was not made from life, but was based on previously drawn sketches.[10] Conrad Freyse raises some doubts about the dating of the work, preferring to attribute its authorship to the painter Johann Philipp Bach (1752–1846), son of Gottlieb Friedrich. According to Freyse, Johann Philipp would have made the pastel around 1780, perhaps taking as a model a sketch actually made by his father in Leipzig decades earlier.[13] First publicly displayed in 1950 by Karl Geiringer, the pastel is currently in a private collection in Munich.[10]

- The Volbach portrait was so named because Mainz professor Fritz Volbach (1861–1940),[14] It was discovered and acquired by Volbach, who in 1903 attracted public attention by publishing it for members of the Neue Bachgesellschaft. It came from Thuringia and was brought to Mainz in 1847 by a musician from Querfurt. A German anatomist from Tübingen, August von Froriep, claimed its authenticity in 1909 by comparing the corresponding details of the skull, but this is currently much disputed, especially due to discrepancies in physiognomy, clothing and hairstyle between it and the skull.[15]

- Bach in Berlin despite putting the inscription Joh. Seb. Bach on the back, some things such as the shape of the head and the details of the face are completely different.[10] This canvas, which belongs to a 1941 private collection in Berlin, was allegedly destroyed in 1945 during World War II.[16]

- Bach Weydenhammer portrait fragment was painted by an unknown artist between 1730 and 1735.[17][18] The painting, which may have belonged to Johann Christian Kittel, a Bach's student, shows the painting somewhat weatherworn and was certainly of a larger size, but only the head has survived. It is currently courtesy of the descendants of Weydenhammer.[18]

- Leipzig, with church and school of St. Thomas's in background appeared on the title page of the first volume of Singende Müse an der Pleisse, a collection of strophic songs published in Leipzig in 1736 by Johann Sigismund Scholze. Teri Noel believes there is a possibility that the two people shown are Bach and his wife Anna Magdalena.[19]

- Bach Silverpoint Drawing was purchased by Erich Fiala in 1937 from a Paris antique dealer and was first made public in 1958 by Heinrich Besseler. It was judged, based on facial features, authentic. Others, however, question his actual identification with Bach. It is currently in the private collection of Fiala in Vienna.[20]

Gallery

Rentsch, 1715

Rentsch, 1715_%E2%80%93_J.S._Bach_as_C%C3%B6then_Court_Kapellmeister_(1717-23).jpg.webp) Ihle, 1717–1723?

Ihle, 1717–1723? Mainingen, 1732–1736?

Mainingen, 1732–1736? Volbach, 1748

Volbach, 1748 Berlin

Berlin Weydenhammer fragment 1730–1735?

Weydenhammer fragment 1730–1735? Leipzig, with church and school of St. Thomas's in background, 1736

Leipzig, with church and school of St. Thomas's in background, 1736 Bach silverpoint drawing

Bach silverpoint drawing

References

- ↑ Buscaroli 2017, p. 1072.

- ↑ Basso 1983, pp. 187–188.

- 1 2 3 Candé 1990, p. 298.

- ↑ "Bach in Arts – Bach Painting". bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ↑ "Bach in Arts – Bach Portrait (Hussmann, replica 1748)". bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ↑ Buscaroli 2017, p. 1071.

- ↑ "Bach in Arts – Bach Painting". bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ↑ "Bach in Arts – Bach Painting". bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ↑ "Bach in Arts – Bach Painting". bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Candé 1990, p. 299.

- ↑ Richards, Annette (20 September 2022). The Temple of Fame and Friendship: Portraits, Music, and History in the C. P. E. Bach Circle. University of Chicago Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-226-81677-7. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ↑ "The Face of Bach – The Meiningen Pastel – Bach Through the Eyes of His Relatives". Archived from the original on 21 November 2001. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- 1 2 "Bach in Arts – Bach Painting". bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ↑ "I ritratti di Johann Sebastian Bach". macbach.org. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ↑ "Bach in Arts – Bach Painting". bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ↑ "Bach in Arts – Bach Painting". bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ↑ "Bach Memorabilia – Bach Painting". bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- 1 2 "The Face of Bach – Queens College Lecture (10) A Description of the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment". npj.com. Archived from the original on 6 May 2001. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ↑ "Bach Memorabilia – Bach Engraving". bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ↑ "Bach in Arts – Bach Painting". bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

Bibliography

- Basso, Alberto (1983). Frau Musika – La vita e le opere di J. S. Bach (1723–1750) (in Italian). Turin: EDT. ISBN 978-88-7063-028-2.

- Buscaroli, Piero (2017). Bach (in Italian). Mondadori. ISBN 978-88-04-68240-0. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- Candé, Roland de (1990). Johann Sebastian Bach. Pordenone: Studio Tesi. ISBN 88-7692-205-9.