| Colorado potato beetle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Coleoptera |

| Infraorder: | Cucujiformia |

| Family: | Chrysomelidae |

| Genus: | Leptinotarsa |

| Species: | L. decemlineata |

| Binomial name | |

| Leptinotarsa decemlineata | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata), also known as the Colorado beetle, the ten-striped spearman, the ten-lined potato beetle, or the potato bug, is a major pest of potato crops. It is about 10 mm (3⁄8 in) long, with a bright yellow/orange body and five bold brown stripes along the length of each of its elytra. Native to the Rocky Mountains,[3] it spread rapidly in potato crops across America and then Europe from 1859 onwards.

Taxonomy

_(14198132866).png.webp)

The Colorado potato beetle was first observed in 1811 by Thomas Nuttall and was formally described in 1824 by American entomologist Thomas Say.[3] The beetles were collected in the Rocky Mountains, where they were feeding on the buffalo bur, Solanum rostratum.[4] The genus Leptinotarsa is assigned to the chrysomelid beetle tribe Chrysomelini (in subfamily Chrysomelinae).

Description

Adult beetles typically are 6–11 mm (0.24–0.43 in) in length and 3 mm (0.12 in) in width. They weigh 50-170 mg.[5] The beetles are orange-yellow in colour with 10 characteristic black stripes on their elytra. The specific name decemlineata, meaning 'ten-lined', derives from this feature.[4][6] Adult beetles may, however, be visually confused with L. juncta, the false potato beetle, which is not an agricultural pest. L. juncta also has alternating black and white strips on its back, but one of the white strips in the center of each wing cover is missing and replaced by a light brown strip.[7]

The orange-pink larvae have a large, 9-segmented abdomen, black head, and prominent spiracles, and may measure up to 15 mm (0.59 in) in length in their final instar stage. The beetle larva has four instar stages. The head remains black throughout these stages, but the pronotum changes colour from black in first- and second-instar larvae to having an orange-brown edge in its third-instar. In fourth-instar larvae, about half the pronotum is coloured light brown.[4][8] This tribe is characterised within the subfamily by round to oval-shaped convex bodies, which are usually brightly coloured, simple claws which separate at the base, open cavities behind the procoxae, and a variable apical segment of the maxillary palp.[9][6]

Distribution

The beetle is most likely native to the area between Colorado and northern Mexico, and was discovered in 1824 by Thomas Say in the Rocky Mountains. It is found in North America, and is present in every state and province except Alaska, California, Hawaii, and Nevada.[4] It now has a wide distribution across Europe and Asia,[10] totalling over 16 million km2.[11]

Its first association with the potato plant (Solanum tuberosum) was not made until about 1859, when it began destroying potato crops in the region of Omaha, Nebraska. Its spread eastward was rapid, at an average distance of 140 km per year.[12] By 1874 it had reached the Atlantic Coast.[4] From 1871, American entomologist Charles Valentine Riley warned Europeans about the potential for an accidental infestation caused by the transportation of the beetle from America.[12] From 1875, several Western European countries, including Germany, Belgium, France, and Switzerland, banned imports of American potatoes to avoid infestation by L. decemlineata.[13]

These controls proved ineffective, as the beetle soon reached Europe. In 1877, L. decemlineata reached the United Kingdom and was first recorded from Liverpool docks, but it did not become established. Many further outbreaks have occurred; the species has been eradicated in the UK at least 163 times. The last major outbreak was in 1976. It remains as a notifiable quarantine pest in the United Kingdom and is monitored by DEFRA to prevent it from becoming established.[14] A cost-benefit analysis from 1981 suggested that the cost of the measures used to exclude L. decemlineata from the UK was less than the likely costs of control if it became established.[15]

Elsewhere in Europe, the beetle became established near USA military bases in Bordeaux during or immediately following World War I and had proceeded to spread by the beginning of World War II to Belgium, the Netherlands, and Spain. The population increased dramatically during and immediately following World War II and spread eastward, and the beetle is now found over much of the continent. After World War II, in the Soviet occupation zone of Germany, almost half of all potato fields were infested by the beetle by 1950. In East Germany, they were known as Amikäfer ('Yankee beetles') following a governmental claim that the beetles were dropped by American planes. In the European Union, it remains a regulated (quarantine) pest for the Republic of Ireland, Balearic Islands, Cyprus, Malta, and southern parts of Sweden and Finland. It is not established in any of these member states, but occasional infestations can occur when, for example, wind blows adults from Russia to Finland.[16][17]

The beetle has the potential to spread to temperate areas of East Asia, India, South America, Africa, New Zealand, and Australia.[18]

Native range of the potato and native and current range of the Colorado beetle

Native range of the potato and native and current range of the Colorado beetle Expansion of the Colorado potato beetle's range in North America, 1859–1876

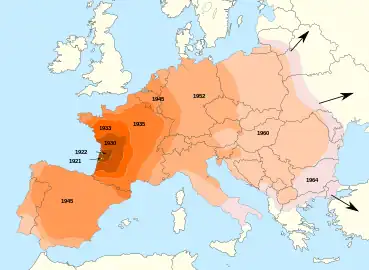

Expansion of the Colorado potato beetle's range in North America, 1859–1876 Expansion of the Colorado potato beetle's range in Europe, 1921–1964

Expansion of the Colorado potato beetle's range in Europe, 1921–1964

Lifecycle

Colorado potato beetle females are very prolific and are capable of laying over 500 eggs in a 4- to 5-week period.[19] The eggs are yellow to orange, and are about 1 mm (0.039 in) long. They are usually deposited in batches of about 30 on the underside of host leaves. Development of all life stages depends on temperature. After 4–15 days, the eggs hatch into reddish-brown larvae with humped backs and two rows of dark brown spots, one row on each side. They feed on the leaves of their host plants. Larvae progress through four distinct growth stages (instars). First instars measure about 1.50 mm (0.059 in) long, and the last (fourth) instars about 8 mm (0.31 in) long. The first through third instars each last about 2–3 days; the fourth lasts 4–7 days. Upon reaching full size, each fourth instar spends several days as a nonfeeding prepupa, which can be recognized by its inactivity and lighter coloration. The prepupae drop to the soil and burrow to a depth of several inches, then pupate.[4] In 5 to 10 days, the adult beetle emerges to feed and mate. This beetle can thus go from egg to adult in as little as 21 days.[19] Depending on temperature, light conditions, and host quality, the adults may enter diapause and delay emergence until spring. They then return to their host plants to mate and feed; overwintering adults may begin mating within 24 hours of spring emergence.[20] In some locations, three or more generations may occur each growing season.[4]

Eggs laid on the underside of a leaf

Eggs laid on the underside of a leaf 1st instar larva after hatching

1st instar larva after hatching 3rd instar stage of larvae

3rd instar stage of larvae 4th instar stage of larva, before pupation

4th instar stage of larva, before pupation Pupa

Pupa Adult beetle after emergence

Adult beetle after emergence Mating adult beetles

Mating adult beetles

Behavior and ecology

Diet

L. decemlineata has a strong association with plants in the family Solanaceae, particularly those of the genus Solanum. It is directly associated with Solanum cornutum (buffalo-bur), Solanum nigrum (black nightshade), Solanum melongena (eggplant or aubergine), Solanum dulcamara (bittersweet nightshade), Solanum luteum (hairy nightshade), Solanum tuberosum (potato), and Solanum elaeagnifolium (silverleaf nightshade). They are also associated with other plants in this family, namely the species Solanum lycopersicum (tomato) and the genus Capsicum (pepper).[21]

Predators

At least 13 insect genera, three spider families, one phalangid (Opiliones), and one mite have been recorded as either generalist or specialized predators of the varying stages of L. decemlineata. These include the ground beetle Lebia grandis, the coccinellid beetles Coleomegilla maculata and Hippodamia convergens, the shield bugs Perillus bioculatus and Podisus maculiventris, various species of the lacewing genus Chrysopa, the wasp genus Polistes, and the damsel bug genus Nabis.[22]

The predatory ground beetle L. grandis is a predator of both the eggs and larvae of L. decemlineata, and its larvae are parasitoids of the pupae. An adult L. grandis may consume up to 23 eggs or 3.3 larvae in a single day.[23]

In a laboratory experiment, Podisus maculiventris was used as a predatory threat to female L. decemlineata specimens, resulting in the production of unviable trophic eggs alongside viable ones; this response to a predator ensured that additional food was available for newly hatched offspring to increase their survival rate. The same experiment also demonstrated the cannibalism of unhatched eggs by newly hatched L. decemlineata larvae as an antipredator response.[24]

| Type | Species | Order | Predates | Location | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parasitoid | Chrysomelobia labidomerae | Acari | Adults | USA, Mexico | [25] |

| Edovum puttleri | Hymenoptera | Eggs | USA, Mexico, Colombia | [26] | |

| Anaphes flavipes | Hymenoptera | Eggs | USA | ||

| Myiopharus aberrans | Diptera | Eggs | USA | ||

| Myiopharus doryphorae | Diptera | Larvae | USA, Canada | ||

| Meigenia mutabilis | Diptera | Larvae | Russia | ||

| Megaselia rufipes | Diptera | Adults | Germany | ||

| Heterorhabditis bacteriophora | Nematoda | Adults | Cosmopolitan | [27] | |

| Heterorhabditis heliothidis | Nematoda | Adults | Cosmopolitan | ||

| Predator | Lebia grandis | Coleoptera | Eggs, Larvae, Adults | USA | |

| Hippodamia convergens | Coleoptera | Eggs, Larvae | USA, Mexico | ||

| Euthyrhynchus floridanus | Hemiptera | Larvae | USA | [28] | |

| Oplomus dichrous | Hemiptera | Eggs, Larvae | USA, Mexico | [29] | |

| Perillus bioculatus | Hemiptera | Eggs, Larvae, Adults | USA, Mexico, Canada | [30] | |

| Podisus maculiventris | Hemiptera | Larvae | USA | [31] | |

| Pselliopus cinctus | Hemiptera | Larvae | USA | ||

| Sinea diadema | Hemiptera | Larvae | USA | ||

| Stiretrus anchorago | Hemiptera | Larvae | USA, Mexico | ||

| Pathogen | Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. tenebrionis |

Bacillales | Larvae | USA, Canada, Europe | |

| Photorhabdus luminescens | Enterobacterales | Adults, Larvae | Cosmopolitan | [32] | |

| Spiroplasma | Entomoplasmatales | Adults, Larvae | North America, Europe | [33] | |

| Beauveria bassiana | Hypocreales | Adults, Larvae | USA | [34] | |

As an agricultural pest

Potato crop pest

Around 1840, L. decemlineata adopted the cultivated potato into its host range and it rapidly became a most destructive pest of potato crops. It is today considered to be the most important insect defoliator of potatoes.[18] It may also cause considerable damage to tomato and eggplant crops with both adults and larvae feeding on the plant's foliage. Larvae may defoliate potato plants resulting in yield losses up to 100% if the damage occurs prior to tuber formation.[35] Larvae may consume 40 cm2 of potato leaves during the entire larval stage, but adults are capable of consuming 10 cm2 of foliage per day.[36]

The economic cost of insecticide resistance is significant, but published data on the subject are minimal.[37] In 1994, total costs of the insecticide and crop losses in the US state of Michigan were $13.3 million, representing 13.7% of the total value of the crop. The estimate of the cost implication of insecticides and crop losses per hectare is $138–368. Long-term increased cost to the Michigan potato industry caused by insecticide resistance in Colorado potato beetle was estimated at $0.9 to $1.4 million each year.[38]

Insecticidal management

The large-scale use of insecticides in agricultural crops effectively controlled the pest until it became resistant to DDT in 1952 and dieldrin in 1958.[39] Insecticides remain the main method of pest control on commercial farms. However, many chemicals are often unsuccessful when used against this pest because of the beetle's ability to rapidly develop insecticide resistance. Different populations in different geographic regions have, between them, developed resistance to all major classes of insecticide,[40][41] although not every population is resistant to every chemical.[40] The species as a whole has evolved resistance to 56 different chemical insecticides.[42] The mechanisms used include improved metabolism of the chemicals, reduced sensitivity of target sites, less penetration and greater excretion of the pesticides, and some changes in the behavior of the beetles.[40]

| Insecticide class | Common examples | Potato | Eggplant | Tomato | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organophosphates | phosmet | X | on US Emergency Planning List of Extremely Hazardous Substances | ||

| disulfoton | X | X | Usage restricted by US government; manufacturer Bayer exited US market 2009 | ||

| Carbamates | carbaryl | X | X | X | Widely used in US |

| carbofuran | X | One of the most toxic carbamates | |||

| Chlorinated hydrocarbons | methoxychlor | X | X | Banned in EU 2002, in USA 2003 | |

| (Cycloldienes) | endosulfan | X | X | X | Acutely toxic, bioaccumulates, endocrine disruptor. Global ban 2012 with exemptions until 2017 |

| Insect growth regulator | azadirachtin | X | X | X | |

| Spinosin | spinosad | X | X | ||

| Avermectin | abamectin | X | X | ||

CPBs have evolved widespread insecticide resistance.[43] No cases without fitness cost or of negative cost are known.[43]

Nonpesticidal management

Bacterial insecticides can be effective if application is targeted towards the vulnerable early-instar larvae. Two strains of the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis produce toxins that kill the larvae.[35] Other forms of pest control, through nonpesticidal management are available. Feeding can be inhibited by applying antifeedants, such as fungicides or products derived from Neem (Azadirachta indica), but these may have negative effects on the plants, as well.[35] The steam distillate of fresh leaves and flowers of tansy (Tanacetum vulgare) contains high levels of camphor and umbellulone, and these chemicals are strongly repellent to L. decemlineata.[44]

Beauveria bassiana (Hyphomycetes) is a pathogenic fungus that infects a wide range of insect species, including the Colorado potato beetle.[45] It has shown to be particularly effective as a biological pesticide for L. decemlineata when used in combination with B. thuringiensis.[46]

Crop rotation is, however, the most important cultural control of L. decemlineata.[18] Rotation may delay the infestation of potatoes and can reduce the build-up of early-season beetle populations because the adults emerging from diapause can only disperse to new food sources by walking.[35] One 1984 study showed that rotating potatoes with nonhost plants reduced the density of early-season adults by 95.8%.[47]

Other cultural controls may be used in combination with crop rotation: Mulching the potato crop with straw early in the growing season may reduce the beetle's ability to locate potato fields, and the mulch creates an environment that favours beetle's predators; Plastic-lined trenches have been used as pitfall traps to catch the beetles as they move toward a field of potatoes in the spring, exploiting their inability to fly immediately after emergence; flamethrowers may also be used to kill the beetles when they are visible at the top of the plant's foliage.[48]

Relationship with humans

Cold War villain

During the Cold War, some countries in the Warsaw Pact claimed that the beetles had been introduced by the CIA in an attempt to reduce food security by destroying the agriculture of the Soviet Union.[49] A widespread campaign was launched against the beetles; posters were put up and school children were mobilized to gather the pests and kill them in benzene or spirit.[49]

Philately

L. decemlineata is an iconic species and has been used as an image on stamps because of its association with the recent history of both North America and Europe. For example, in 1956, Romania issued a set of four stamps calling attention to the campaign against insect pests,[51] and it was featured on a 1967 stamp issued in Austria.[52] The beetle also appeared on stamps issued in Benin, Tanzania, the United Arab Emirates, and Mozambique.[53]

In popular culture

Neapolitan mandolins (also called Italian mandolins) are often called tater bugs,[54][55] a nickname given by American luthier Orville Gibson, because the shape and stripes of the different color wood strips resemble the back of the Colorado beetle.[56]

The fans of Alemannia Aachen carry the nickname "Kartoffelkäfer", from the German name for the Colorado beetle, because of striped yellow-black jerseys of the team.[57][58]

During the 2014 pro-Russian unrest in Ukraine, the word kolorady, from the Ukrainian and Russian term for Colorado beetle (Ukrainian: жук колорадський, Russian: колорадский жук), gained popularity among Ukrainians as a derogatory term to describe pro-Russian separatists in the Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts (provinces) of Eastern Ukraine. The nickname reflects the similarity of black and orange stripes on St. George's ribbons worn by many of the separatists.[59]

Notes

References

- ↑ "Leptinotarsa decemlineata". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- ↑ "Leptinotarsa decemlineata, Colorado Potato Beetle: Synonyms". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- 1 2 Say, Thomas (1824). "Descriptions of Coleopterous insects collected in the late expedition to the Rocky Mountains, performed by order of Mr. Calhoun, Secretary of War, under the command of Major Long". Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 3 (3): 403–462.; see pp. 453–454: "Doryphora, Illig.: D. 10-lineata".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 University of Florida (2007). "Featured creatures: Leptinotarsa spp". Retrieved 2017-03-19.

- ↑ "Colorado Potato Beetle Facts". 25 October 2018. Retrieved 2021-02-20.

- 1 2 Boiteau, G.; Le Blanc, J.-P. R. (1992). "Colorado potato beetle LIFE STAGES" (PDF). Agriculture Canada. Retrieved 2017-03-23.

- ↑ "Species Leptinotarsa juncta - False Potato Beetle - BugGuide.Net". bugguide.net. Iowa State University. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ↑ "Doryphorini". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 2017-05-23.

- ↑ Jacques Jr., R. L. (1988). The Potato Beetles: The genus Leptinotarsa in North America. Brill. ISBN 978-0-916846-40-4.

- ↑ "Species Leptinotarsa decemlineata - Colorado Potato Beetle". BugGuide. 2017. Retrieved 2017-03-19.

- ↑ Weber, D. (2003). "Colorado beetle: pest on the move". Pesticide Outlook. 14 (6): 256–259. doi:10.1039/b314847p. Archived from the original on 2020-07-28. Retrieved 2018-12-29.

- 1 2 Feytaud, J. (1949). La pomme de terre (in French). Presses universitaires de France. pp. 98–104.

- ↑ Sorensen, W. C. (1995). Brethren of the net: American entomology, 1840-1880. History of American science and technology series. University of Alabama Press. pp. 124–125. ISBN 9780817307554.

- ↑ "Invasion history: Leptinotarsa decemlineata, Colorado Beetle". Non-Native Species Secretariat (DEFRA). 2017. Archived from the original on 2020-07-28. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- ↑ Aitkenhead, P. (1981). "Colorado beetle - recent work in preventing its establishment in Britain". Bulletin, Organisation Européenne et Méditerranéenne pour la Protection des Plantes. 11 (3): 225–234. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2338.1981.tb01928.x.

- ↑ Lehmann, P. "The Colorado potato beetle is the grandmaster of adaptation". University of Jyväskylä. Archived from the original on 2017-05-10. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- ↑ "The Colorado beetle". Finnish Food Safety Authority. 2016. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 Alyokhin, A. (2009). "Colorado potato beetle management on potatoes: current challenges and future prospects" (PDF). In Tennant, P.; Benkeblia, N. (eds.). Potato II. Fruit, Vegetable and Cereal Science and Biotechnology 3 (Special Issue 1). pp. 10–19.

- 1 2 3 Bessin, R. "Colorado Potato Beetle Management". University of Kentucky College of Agriculture. Retrieved 2017-07-11.

- ↑ Ferro, D. N.; Alyokhin, A. V.; Tobin, D. B. (1999). "Reproductive status and flight activity of the overwintered Colorado potato beetle". Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata. 91 (3): 443–448. doi:10.1046/j.1570-7458.1999.00512.x. S2CID 85300335.

- ↑ "Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say)". Biological Records Centre -Database of Insects and their Food Plants. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ↑ Hilbeck, A.; Kennedy, G. G. (1996). "Predators Feeding on the Colorado Potato Beetle in Insecticide-Free Plots and Insecticide-Treated Commercial Potato Fields in Eastern North Carolina". Biological Control. 6 (2): 273–282. doi:10.1006/bcon.1996.0034.

- ↑ Weber, D. C.; Rowley, D. L.; Greenstone, M. H.; Athanas, M. M. (2006). "Prey preference and host suitability of the predatory and parasitoid carabid beetle, Lebia grandis, for several species of Leptinotarsa beetles". Journal of Insect Science. 6 (9): 1–14. doi:10.1673/1536-2442(2006)6[1:ppahso]2.0.co;2. PMC 2990295. PMID 19537994.

- ↑ Tigreros, N.; Norris, R. H.; Wang, E.; Thaler, J. S. (2017). "Maternally induced intraclutch cannibalism: an adaptive response to predation risk?". Ecology Letters. 20 (4): 487–494. doi:10.1111/ele.12752. PMID 28295886.

- ↑ Drummond, F. A.; Casagrande, R. A.; Logan, P. A. (1992). "Impact of the parasite, Chrysomelobia labidomerae Eickwort, on the Colorado potato beetle". International Journal of Acarology. 18 (2): 107–115. doi:10.1080/01647959208683940.

- ↑ Grissell, E. E. (1981). "Edovum puttleri, n.g., n.sp. (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae), an egg parasite of the Colorado potato beetle (Chrysomelidae)". Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington. 83 (4): 790–796.

- ↑ Ebrahimi, L.; Niknam, G.; Dunphy, G. B. (2011). "Hemocyte Responses of the Colorado Potato Beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata, and the Greater Wax Moth, Galleria mellonella, to the Entomopathogenic Nematodes, Steinernema feltiae and Heterorhabditis bacteriophora". Journal of Insect Science. 11 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1673/031.011.7501. PMC 3281463. PMID 21867441.

- ↑ Chittenden, F. H. (1911). "On the natural enemies of the Colorado potato beetle". Bulletin United States Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Entomology. 82: 85–88.

- ↑ Drummond, F. A.; Casagrande, R. A.; Groden, E. (1987). "Biology of Oplomus dichrous (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) and Its Potential to Control Colorado Potato Beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae)". Environmental Entomology. 16 (3): 633–638. doi:10.1093/ee/16.3.633.

- ↑ Cloutier, C.; Bauduin, F. (1995). "Biological Control of the Colorado Potato Beetle Leptinotarsa Decemlineata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in Quebec by Augmentative Releases of the Two-Spotted Stinkbug Perillus Bioculatus (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae)". The Canadian Entomologist. 127 (2): 195–212. doi:10.4039/ent127195-2. S2CID 85720476.

- ↑ Richman, D. B.; Mead, F. W.; Fasulo, T. R. "Spined Soldier Bug, Podisus maculiventris (Say)" (PDF). University of Florida, IFAS Extension. Retrieved 2017-07-31.

- ↑ Blackburn, M. B.; Domek, J. M; Gelman, D. B; Hu, J. S. (2005). "The broadly insecticidal Photorhabdus luminescens toxin complex a (Tca): activity against the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata, and sweet potato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci". Journal of Insect Science. 5 (1): 32. doi:10.1093/jis/5.1.32. PMC 1615239. PMID 17119614.

- ↑ Breithaupt, J. (4 November 2012). "Leptinotarsa decemlineata: Management". Ecoport. Retrieved 2017-07-28.

- ↑ Bonnemaison, L. (1961). Les ennemis animaux des plantes cultivées et des forêts, vol. II (in French). p. 98.

- 1 2 3 4 Gullan, P. J.; Cranston, P. S., eds. (1994). "15.2.1 Insecticide resistance". The Insects: An Outline of Entomology. Chapman & Hall. pp. 404–407. ISBN 978-0-412-49360-7.

- ↑ Ferro, D. N.; Logan, J. A.; Voss, R. H.; Elkinton, J. S. (1985). "Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) temperature-dependent growth and feeding rates". Environmental Entomology. 14 (3): 343–348. doi:10.1093/ee/14.3.343.

- ↑ "Plantwise Technical Factsheet, Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata)". Plantwise. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ↑ Grafius, E. (1997). "Economic Impact of Insecticide Resistance in the Colorado Potato Beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) on the Michigan Potato Industry". Journal of Economic Entomology. 90 (5): 1144–1151. doi:10.1093/jee/90.5.1144.

- ↑ Alyokhin, A.; Baker, M.; Mota-Sanchez, D.; Dively, G.; Grafius, E. (2008). "Colorado Potato Beetle Resistance to Insecticides". American Journal of Potato Research. 85 (6): 395–413. doi:10.1007/s12230-008-9052-0. S2CID 41206911.

- 1 2 3 Alyokhin, A.; Baker, M.; Mota-Sanchez, D.; Dively, G.; Grafius, E. (2008). "Colorado potato beetle resistance to insecticides". American Journal of Potato Research. 85 (6): 395–413. doi:10.1007/s12230-008-9052-0. S2CID 41206911.

- ↑ Hare, J. D. (1990). "Ecology and Management of the Colorado Potato Beetle". Annual Review of Entomology. 35: 81–100. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.35.010190.000501.

- ↑ "Leptinotarsa decemlineata". Arthropod Pesticide Resistance Database (Michigan State University). Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- 1 2 Kliot, Adi; Ghanim, Murad (2012). "Fitness costs associated with insecticide resistance". Pest Management Science. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 68 (11): 1431–1437. doi:10.1002/ps.3395. ISSN 1526-498X. PMID 22945853.

- ↑ Schearer, W. R. (1984). "Components of Oil of Tansy (Tanacetum vulgare) that repel Colorado potato beetles (Leptinotarsa decemlineata)". Journal of Natural Products. 47 (6): 964–969. doi:10.1021/np50036a009.

- ↑ "University of Connecticut Extension". Archived from the original on 2006-09-01. Retrieved 2017-05-23.

- ↑ Wraight, S. P.; Ramos, M. E. (2017). "Characterization of the synergistic interaction between Beauveria bassiana strain GHA and Bacillus thuringiensis morrisoni strain tenebrionis applied against Colorado potato beetle larvae". Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 144: 47–57. doi:10.1016/j.jip.2017.01.007. PMID 28108175.

- ↑ Wright, R. J. (1984). "Evaluation of crop rotation for control of Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in commercial potato fields on Long Island". Journal of Economic Entomology. 77 (5): 1254–1259. doi:10.1093/jee/77.5.1254.

- ↑ Grubinger, V. (2004). "Colorado Potato Beetle". The University of Vermont. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- 1 2 Sindelar, D. (29 April 2014). "What's Orange and Black and Bugging Ukraine?". Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

Ukraine’s Reins Weaken as Chaos Spreads, The New York Times (4 May 2014)

(in Ukrainian) Lyashko in Lviv poured green, Ukrayinska Pravda (18 June 2014) - ↑ Saringer, G. (2002). "The Years Spent by Tibor Jermy Academician in Keszthely" (PDF). Acta Zoologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 48: 33–42.

- ↑ "Stamp catalog : Stamp › Colorado Potato Beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata)". 2003–2017. Retrieved 2017-05-23.

- ↑ Skaptason, J. L. (2000-10-28). "Skaps' bug stamps - Austria". Archived from the original on 2014-04-18. Retrieved 2017-05-23.

- ↑ "Potatobeetle.org Memorabilia". 2008. Retrieved 2017-05-23.

- ↑ Greg Horne (2005). Beginning Mandolin. Alfred Music Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-739037-32-4.

- ↑ Don Julin; Scott Tichenor (2012). Mandolin For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 282. ISBN 978-1-119942-76-4.

- ↑ Fred Sokolow (2014). 101 Mandolin Tips. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-1-495009-03-7.

- ↑ Marco Stoffel (15 February 2005). ""Kartoffelkäfer" sind die beste Werbung". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- ↑ "Warum "DieKartoffelkaefer.de" ?". Archived from the original on 2022-01-24. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- ↑ Kramermay, A. E. (4 May 2014). "Ukraine's Reins Weaken as Chaos Spreads". New York Times. Retrieved 2020-07-12.