.jpeg.webp)

Shellac (/ʃəˈlæk/)[1] is a resin secreted by the female lac bug on trees in the forests of India and Thailand. Chemically, it is mainly composed of aleuritic acid, jalaric acid, shellolic acid, and other natural waxes.[2] It is processed and sold as dry flakes and dissolved in alcohol to make liquid shellac, which is used as a brush-on colorant, food glaze and wood finish. Shellac functions as a tough natural primer, sanding sealant, tannin-blocker, odour-blocker, stain, and high-gloss varnish. Shellac was once used in electrical applications as it possesses good insulation qualities and seals out moisture. Phonograph and 78 rpm gramophone records were made of shellac until they were replaced by vinyl long-playing records from 1948 onwards.[3]

From the time shellac replaced oil and wax finishes in the 19th century, it was one of the dominant wood finishes in the western world until it was largely replaced by nitrocellulose lacquer in the 1920s and 1930s.

Etymology

Shellac comes from shell and lac, a partial calque of French laque en écailles, 'lac in thin pieces', later gomme-laque, 'gum lac'.[4] Most European languages (except Romance ones and Greek) have borrowed the word for the substance from English or from the German equivalent Schellack.[5]

Production

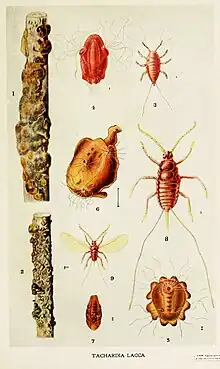

Shellac is scraped from the bark of the trees where the female lac bug, Kerria lacca (order Hemiptera, family Kerriidae, also known as Laccifer lacca), secretes it to form a tunnel-like tube as it traverses the branches of the tree. Though these tunnels are sometimes referred to as "cocoons", they are not cocoons in the entomological sense.[6] This insect is in the same superfamily as the insect from which cochineal is obtained. The insects suck the sap of the tree and excrete "sticklac" almost constantly. The least-coloured shellac is produced when the insects feed on the kusum tree (Schleichera).[7]

The number of lac bugs required to produce 1 kilogram (2.2 lb) of shellac has variously been estimated between 50,000 and 300,000.[8][9] The root word lakh is a unit in the Indian numbering system for 100,000 and presumably refers to the huge numbers of insects that swarm on host trees, up to 150 per square inch (23/cm2).[10]

The raw shellac, which contains bark shavings and lac bugs removed during scraping, is placed in canvas tubes (much like long socks) and heated over a fire. This causes the shellac to liquefy, and it seeps out of the canvas, leaving the bark and bugs behind. The thick, sticky shellac is then dried into a flat sheet and broken into flakes, or dried into "buttons" (pucks/cakes), then bagged and sold. The end-user then crushes it into a fine powder and mixes it with ethyl alcohol before use, to dissolve the flakes and make liquid shellac.[11]

Liquid shellac has a limited shelf life (about 1 year), so is sold in dry form for dissolution before use. Liquid shellac sold in hardware stores is often marked with the production (mixing) date, so the consumer can know whether the shellac inside is still good. Some manufacturers (e.g., Zinsser) have ceased labeling shellac with the production date, but the production date may be discernible from the production lot code. Alternatively, old shellac may be tested to see if it is still usable: a few drops on glass should dry to a hard surface in roughly 15 minutes. Shellac that remains tacky for a long time is no longer usable. Storage life depends on peak temperature, so refrigeration extends shelf life.

The thickness (concentration) of shellac is measured by the unit "pound cut", referring to the amount (in pounds) of shellac flakes dissolved in a gallon of denatured alcohol. For example: a 1-lb. cut of shellac is the strength obtained by dissolving one pound of shellac flakes in a gallon of alcohol (equivalent to 120 grams per litre).[12] Most pre-mixed commercial preparations come at a 3-lb. cut. Multiple thin layers of shellac produce a significantly better end result than a few thick layers. Thick layers of shellac do not adhere to the substrate or to each other well, and thus can peel off with relative ease; in addition, thick shellac will obscure fine details in carved designs in wood and other substrates.

Shellac naturally dries to a high-gloss sheen. For applications where a flatter (less shiny) sheen is desired, products containing amorphous silica, such as "Shellac Flat", may be added to the dissolved shellac.[13]

Shellac naturally contains a small amount of wax (3%–5% by volume), which comes from the lac bug. In some preparations, this wax is removed (the resulting product being called "dewaxed shellac"). This is done for applications where the shellac will be coated with something else (such as paint or varnish), so the topcoat will adhere. Waxy (non-dewaxed) shellac appears milky in liquid form, but dries clear.

Colours and availability

Shellac comes in many warm colours, ranging from a very light blonde ("platina") to a very dark brown ("garnet"), with many varieties of brown, yellow, orange and red in between. The colour is influenced by the sap of the tree the lac bug is living on and by the time of harvest. Historically, the most commonly sold shellac is called "orange shellac", and was used extensively as a combination stain and protectant for wood panelling and cabinetry in the 20th century.

Shellac was once very common anywhere paints or varnishes were sold (such as hardware stores). However, cheaper and more abrasion- and chemical-resistant finishes, such as polyurethane, have almost completely replaced it in decorative residential wood finishing such as hardwood floors, wooden wainscoting plank panelling, and kitchen cabinets. These alternative products, however, must be applied over a stain if the user wants the wood to be coloured; clear or blonde shellac may be applied over a stain without affecting the colour of the finished piece, as a protective topcoat. "Wax over shellac" (an application of buffed-on paste wax over several coats of shellac) is often regarded as a beautiful, if fragile, finish for hardwood floors. Luthiers still use shellac to French polish fine acoustic stringed instruments, but it has been replaced by synthetic plastic lacquers and varnishes in many workshops, especially high-volume production environments.[14]

Shellac dissolved in alcohol, typically more dilute than as used in French polish, is now commonly sold as "sanding sealer" by several companies. It is used to seal wooden surfaces, often as preparation for a final more durable finish; it reduces the amount of final coating required by reducing its absorption into the wood.

Properties

Shellac is a natural bioadhesive polymer and is chemically similar to synthetic polymers.[15] It can thus be considered a natural form of plastic.

With a melting point of 75 °C (167 °F), it can be classed as a thermoplastic used to bind wood flour, the mixture can be moulded with heat and pressure.

Shellac scratches more easily than most lacquers and varnishes, and application is more labour-intensive, which is why it has been replaced by plastic in most areas. Shellac is much softer than Urushi lacquer, for instance, which is far superior with regard to both chemical and mechanical resistance. But damaged shellac can easily be touched up with another coat of shellac (unlike polyurethane, which chemically cures to a solid) because the new coat merges with and bonds to the existing coat(s).

Shellac is soluble in alkaline solutions of ammonia, sodium borate, sodium carbonate, and sodium hydroxide, and also in various organic solvents. When dissolved in alcohol (typically denatured ethanol) for application, shellac yields a coating of good durability and hardness.

Upon mild hydrolysis shellac gives a complex mix of aliphatic and alicyclic hydroxy acids and their polymers that varies in exact composition depending upon the source of the shellac and the season of collection. The major component of the aliphatic component is aleuritic acid, whereas the main alicyclic component is shellolic acid.[16]

Shellac is UV-resistant, and does not darken as it ages (though the wood under it may do so, as in the case of pine).[17]

History

The earliest written evidence of shellac goes back 3,000 years, but shellac is known to have been used earlier.[17] According to the ancient Indian epic poem, the Mahabharata, an entire palace was built out of dried shellac.[17]

Shellac was uncommonly used as a dyestuff for as long as there was a trade with the East Indies. According to Merrifield,[18] shellac was first used as a binding agent in artist's pigments in Spain in the year 1220.

The use of overall paint or varnish decoration on large pieces of furniture was first popularised in Venice (then later throughout Italy). There are a number of 13th-century references to painted or varnished cassone, often dowry cassone that were made deliberately impressive as part of dynastic marriages. The definition of varnish is not always clear, but it seems to have been a spirit varnish based on gum benjamin or mastic, both traded around the Mediterranean. At some time, shellac began to be used as well. An article from the Journal of the American Institute of Conservation describes using infrared spectroscopy to identify shellac coating on a 16th-century cassone.[19] This is also the period in history where "varnisher" was identified as a distinct trade, separate from both carpenter and artist.

Another use for shellac is sealing wax.[20] The widespread use of shellac seals in Europe dates back to the 17th century, thanks to the increasing trade with India.[21]

Uses

Historical

In the early- and mid-twentieth century, orange shellac was used as a one-product finish (combination stain and varnish-like topcoat) on decorative wood panelling used on walls and ceilings in homes, particularly in the US. In the American South, use of knotty pine plank panelling covered with orange shellac was once as common in new construction as drywall is today. It was also often used on kitchen cabinets and hardwood floors, prior to the advent of polyurethane.

Until the advent of vinyl, most gramophone records were pressed from shellac compounds.[22][23] From 1921 to 1928, 18,000 tons of shellac were used to create 260 million records for Europe.[10] In the 1930s, it was estimated that half of all shellac was used for gramophone records.[24] Use of shellac for records was common until the 1950s and continued into the 1970s in some non-Western countries, as well as for some children's records.[25][26]

Until recent advances in technology, shellac (French polish) was the only glue used in the making of ballet dancers' pointe shoes, to stiffen the box (toe area) to support the dancer en pointe. Many manufacturers of pointe shoes still use the traditional techniques, and many dancers use shellac to revive a softening pair of shoes.[27]

Shellac was historically used as a protective coating on paintings.

Sheets of Braille were coated with shellac to help protect them from wear due to being read by hand.

Shellac was used from the mid-nineteenth century to produce small moulded goods such as picture frames, boxes, toilet articles, jewelry, inkwells and even dentures. Advances in plastics have rendered shellac obsolete as a moulding compound.[28]

Shellac (both orange and white varieties) was used both in the field and laboratory to glue and stabilise dinosaur bones until about the mid-1960s. While effective at the time, the long-term negative effects of shellac (being organic in nature) on dinosaur bones and other fossils is debated, and shellac is very rarely used by professional conservators and fossil preparators today.[29]

Shellac was used for fixing inductor, motor, generator and transformer windings. It was applied directly to single-layer windings in an alcohol solution. For multi-layer windings, the whole coil was submerged in shellac solution, then drained and placed in a warm place to allow the alcohol to evaporate. The shellac locked the wire turns in place, provided extra insulation, prevented movement and vibration and reduced buzz and hum. In motors and generators it also helps transfer force generated by magnetic attraction and repulsion from the windings to the rotor or armature. In more recent times, shellac has been replaced in these applications by synthetic resins such as polyester resin. Some applications use shellac mixed with other natural or synthetic resins, such as pine resin or phenol-formaldehyde resin, of which Bakelite is the best known, for electrical use. Mixed with other resins, barium sulfate, calcium carbonate, zinc sulfide, aluminium oxide and/or cuprous carbonate (malachite), shellac forms a component of heat-cured capping cement used to fasten the caps or bases to the bulbs of electric lamps.

Current uses

It is the central element of the traditional "French polish" method of finishing furniture, fine string instruments, and pianos.

Shellac, being edible, is used as a glazing agent on pills (see excipient) and sweets, in the form of pharmaceutical glaze (or, "confectioner's glaze"). Because of its acidic properties (resisting stomach acids), shellac-coated pills may be used for a timed enteric or colonic release.[30] Shellac is used as a 'wax' coating on citrus fruit to prolong its shelf/storage life. It is also used to replace the natural wax of the apple, which is removed during the cleaning process.[31] When used for this purpose, it has the food additive E number E904.[32]

Shellac is an odour and stain blocker and so is often used as the base of "all-purpose" primers. Although its durability against abrasives and many common solvents is not very good, shellac provides an excellent barrier against water vapour penetration. Shellac-based primers are an effective sealant to control odours associated with fire damage.[33]

Shellac has traditionally been used as a dye for cotton and, especially, silk cloth in Thailand, particularly in the north-eastern region.[34] It yields a range of warm colours from pale yellow through to dark orange-reds and dark ochre.[35] Naturally dyed silk cloth, including that using shellac, is widely available in the rural northeast, especially in Ban Khwao District, Chaiyaphum province. The Thai name for the insect and the substance is "khrang" (Thai: ครั่ง).

Wood finish

Wood finishing is one of the most traditional and still popular uses of shellac mixed with solvents or alcohol. This dissolved shellac liquid, applied to a piece of wood, is an evaporative finish: the alcohol of the shellac mixture evaporates, leaving behind a protective film.[36]

Shellac as wood finish is natural and non-toxic in its pure form. A finish made of shellac is UV-resistant. For water-resistance and durability, it does not keep up with synthetic finishing products.[37]

Because it is compatible with most other finishes, shellac is also used as a barrier or primer coat on wood to prevent the bleeding of resin or pigments into the final finish, or to prevent wood stain from blotching.[38]

Other

Shellac is used:

- in the tying of artificial flies for trout and salmon, where the shellac was used to seal all trimmed materials at the head of the fly.

- in combination with wax for preserving and imparting a shine to citrus fruits, such as lemons and oranges.[39][40]

- in dental technology, where it is occasionally used in the production of custom impression trays and temporary denture baseplate production.[41]

- as a binder in India ink.[42]

- for bicycles, as a protective and decorative coating for bicycle handlebar tape,[43] and as a hard-drying adhesive for tubular tyres, particularly for track racing.[44]

- for re-attaching ink sacs when restoring vintage fountain pens, the orange variety preferably.

- applied as a coating with either a standard or modified Huon-Stuehrer nozzle, can be economically micro-sprayed onto various smooth candies, such as chocolate coated peanuts. Irregularities on the surface of the product being sprayed may result in the formation of unsightly aggregates ("lac-aggs") which precludes the use of this technique on foods such as walnuts or raisins.

- for fixing pads to the key-cups of woodwind instruments.

- for luthierie applications, to bind wood fibres down and prevent tear out on the soft spruce soundboards.

- to stiffen and impart water-resistance to felt hats, for wood finishing[45] and as a constituent of gossamer (or goss for short), a cheesecloth fabric coated in shellac and ammonia solution used in the shell of traditional silk top and riding hats.

- for mounting insects, in the form of a gel adhesive mixture composed of 75% ethyl alcohol.[46]

- as a binder in the fabrication of abrasive wheels,[47] imparting flexibility and smoothness not found in vitrified (ceramic bond) wheels. 'Elastic' bonded wheels typically contain plaster of paris, yielding a stronger bond when mixed with shellac; the mixture of dry plaster powder, abrasive (e.g. corundum/aluminium oxide Al2O3), and shellac are heated and the mixture pressed in a mould.

- in fireworks pyrotechnic compositions as a low-temperature fuel, where it allows the creation of pure 'greens' and 'blues'- colours difficult to achieve with other fuel mixes.

- in jewellery; shellac is often applied to the top of a 'shellac stick' in order to hold small, complex, objects. By melting the shellac, the jeweller can press the object (such as a stone setting mount) into it. The shellac, once cool, can firmly hold the object, allowing it to be manipulated with tools.[48]

- in watchmaking, due to its low melting temperature (about 80–100 °C (176–212 °F)), shellac is used in most mechanical movements to adjust and adhere pallet stones to the pallet fork and secure the roller jewel to the roller table of the balance wheel. Also for securing small parts to a 'wax chuck' (faceplate) in a watchmakers' lathe.[49]

- in the early twentieth century, it was used to protect some military rifle stocks.[50]

- in Jelly Belly jelly beans, in combination with beeswax to give them their final buff and polish.[51]

- in modern traditional archery, shellac is one of the hot-melt glue/resin products used to attach arrowheads to wooden or bamboo arrow shafts.[52][53]

- in alcohol solution as sanding sealer, widely sold to seal sanded surfaces, typically wooden surfaces before a final coat of a more durable finish. Similar to French polish but more dilute.[54]

- as a topcoat in nail polish (although not all nail polish sold as "shellac" contains shellac, and some nail polish not labelled in this way does)

- in sculpture, to seal plaster and in conjunction with wax or oil-soaps, to act as a barrier during mold-making processes

- as a dilute solution in the sealing of harpsichord soundboards, protecting them from dust and buffering humidity changes while maintaining a bare-wood appearance.

Gallery

Blonde shellac flakes

Blonde shellac flakes Dewaxed Bona (L) and Waxy #1 Orange (R) shellac flakes. The latter—orange shellac—is the traditional shellac used for decades to finish wooden wall paneling, kitchen cabinets and tool handles.

Dewaxed Bona (L) and Waxy #1 Orange (R) shellac flakes. The latter—orange shellac—is the traditional shellac used for decades to finish wooden wall paneling, kitchen cabinets and tool handles. Closeup of Waxy #1 Orange (L) and Dewaxed Bona (R) shellac flakes. The former—orange shellac—is the traditional shellac used for centuries to finish wooden wall paneling and kitchen cabinets.

Closeup of Waxy #1 Orange (L) and Dewaxed Bona (R) shellac flakes. The former—orange shellac—is the traditional shellac used for centuries to finish wooden wall paneling and kitchen cabinets. "Quick and dirty" example of a pine board coated with 1–5 coats of Dewaxed Dark shellac (a darker version of traditional orange shellac)

"Quick and dirty" example of a pine board coated with 1–5 coats of Dewaxed Dark shellac (a darker version of traditional orange shellac)

See also

References

- ↑ "Shellac". Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255771177_Natural_resin_shellac_as_a_substrate_and_a_dielectric_layer_for_organic_field-effect_transistors/figures?lo=1 Chemical composition of Shellac

- ↑ Read, Oliver; Welch, Walter L., From Tin Foil to Stereo, U.S.A., 1959

- ↑ "shellac". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ Smith, Peter (15 December 2016). "§4. The Indo-European Family of Languages". Greek and Latin Roots: Part I – Latin. University of Victoria.

- ↑ Schad, Beverly; Smith, Houston; Cheng, Brian; Scholten, Jeff; VanNess, Eric; Riley, Tom (1 September 2013). "Coating and Taste Masking with Shellac". Pharmaceutical Technology. 2013 (5).

- ↑ Baboo, B.; Goswami, D. N. (2010). Processing Chemistry and Applications of Lac. Indian Council of Agricultural Research. p. 76.

The resin obtained from Schleichera oleosa was superior to other resins in regard to some industrially important parameters e.g., flow (highest), heat polymerization time (longest) and colour index (lowest).

- ↑ Yacoubou, Jeanne (30 November 2010). "Q & A on Shellac". Vegetarian Resource Group. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ↑ Velji, Vijay (2010). "Shellac Origins and Manufacture". shellacfinishes.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- 1 2 Berenbaum, May (1993). Ninety-nine More Maggots, Mites, and Munchers. University of Illinois Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-252-02016-2.

- ↑ "How and why to mix fresh shellac". www.stewmac.com. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ↑ "Dissolving & Mixing Shellac Flakes: Shellac 'Pound Cut' Chart". shellac.net. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ↑ "American Woodworker: Tips for Using Shellac". Archived from the original on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- ↑ French polishing tutorial for guitars

- ↑ https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/shellac gives the chief component as 9,10,15-trihydroxypentadecanoic acid and also (2R,6S,7R,10S)-10-hydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-6-methyltricycloundec-8-ene-2,8-dicarboxylic acid, molecular formula C30H50O11 with a molecular weight of 586.7 g/mol

- ↑ Merck Index, 9th Ed. page 8224.

- 1 2 3 Naturalhandyman.com : DEFEND, PRESERVE, AND PROTECT WITH SHELLAC : The story of shellac

- ↑ Merrifield, Mary (1849). Original Treatises on the Art of Painting. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publ. ISBN 978-0-486-40440-0.

- ↑ Derrick, Michele R.; Stulik, Dusan C.; Landry, James M.; Bouffard, Steven P. (1992). "Furniture finish layer identification by infrared linear mapping microspectroscopy". Journal of the American Institute of Conservation. 31 (2, Article 6): 225 to 236. doi:10.2307/3179494. JSTOR 3179494. Archived from the original on 6 July 2009. Retrieved 16 May 2008.

- ↑ Woods, C. (1994). "The Nature and Treatment of Wax and Shellac Seals". Journal of the Society of Archivists. 15 (2): 203–214. doi:10.1080/00379819409511747.

- ↑ Jenkinson, Hilary (22 May 1924). "Some Notes on the Preservation, Moulding and Casting of Seals". The Antiquaries Journal. 4 (4): 388–403. doi:10.1017/S0003581500006193.

- ↑ Rheding, Alexander (2006). "On the Record". Cambridge Opera Journal. 18 (1): 59–82. doi:10.1017/S0954586706002102. S2CID 231810582.

- ↑ Melillo, Edward (2014). "Global Entomologies: Insects, Empires, and the 'Synthetic Age' in World History". Past & Present. 223: 233–270. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtt026.

- ↑ "How Shellac Is Manufactured". The Mail (Adelaide, SA : 1912–1954). 18 December 1937. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ↑ "My Turntable Has 3 Speeds But Are 78 RPM Records Still Made? | Vinyl Bro | Elevate Your Music". 28 December 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ↑ "The history of 78 RPM recordings | Yale University Library". web.library.yale.edu. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ↑ "Maintenance of Pointe Shoes – Bloch Australia". Bloch Australia. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ↑ Freinkel, Susan. "A Brief History of Plastic's Conquest of the World". Scientific American. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ↑ "PaleoPortal Fossil Preparation | Tips". preparation.paleo.amnh.org. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ↑ Shellac film coatings providing release at selected pH and method – US Patent 6620431 Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "US Apple: Consumers – FAQs: Apples and Wax". Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ "Bleached Shellac". Creasia Group. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ↑ Stanton, Cole. "Solutions by Sixes and Sevens: Smoke Sealers during Smoke Odor & Fire Damage Restoration". Restoration & Remediation Magazine. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ↑ Suanmuang Tulaphan, Phunsap, Silk Dyeing With Natural Dyestuffs in Northeastern Thailand, 1999, p. 26-30 (in Thai)

- ↑ Punyaprasop, Daranee (Ed.)Colour And Pattern On Native Cloth, 2001, p. 253, 256 (in Thai)

- ↑ Marshall, Chris (2004). Woodworking Tools and Techniques: An Introduction to Basic Woodworking. Creative Publishing International, US. p. 137.

- ↑ "Wood Finishing FAQs: Shellac vs. Polyurethane vs. Varnish". TheDIYhammer. 31 July 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ↑ Shellac, WoodworkDetails.com: Shellac as a Woodworking Finish

- ↑ Sommerlad, Joe (22 August 2022). "Why not all fruit is suitable for vegans". The Independent. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ↑ Khorram, Fereshteh; Ramezanian, Asghar; Hosseini, Seyyed Mohammad Hashem (18 November 2017). "Shellac, gelatin and Persian gum as alternative coating for orange fruit". Scientia Horticulturae. 225: 22–28. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2017.06.045.

- ↑ Azouka, A.; Huggett, R.; Harrison, A. (1993). "The production of shellac and its general and dental uses: a review". Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 20 (4): 393–400. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2842.1993.tb01623.x.

- ↑ "Ink". MoMA. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ↑ "Shellac & Twine makes Handlebar fine". Out Your Backdoor. 21 August 2005. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ Mounting Tubular Tires by Jobst Brandt

- ↑ Jewitt, Jeff. "Shellac: A traditional finish still yields superb results". Antique Restorers. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ Fly Times: Shellac gel for insect mounting

- ↑ Stephen Malkin; Changsheng Guo (2008). Grinding Technology: Theory and Applications of Machining With Abrasives. Industrial Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780831132477.

- ↑ "Stone Setting Tools FAQs". Ganoksin. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ↑ "Shellac". watchmaking journey. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ↑ "What kind of finish is on my stock?". Russian Mosin Nagant Forum. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ↑ Q&A – Jelly Belly jelly beans Archived 5 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Sapp, Rick (2013). The Ultimate Guide to Traditional Archery. ISBN 9781626365360.

- ↑ "Part of a Quiver | Tibetan or Mongolian". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ Dezeil, Chris. "What is a Sanding Sealer?".

External links

- Shellac.net US shellac vendor – properties and uses of dewaxed and non-dewaxed shellac

- The Story of Shellac (history)

- DIYinfo.org's Shellac Wiki, practical information on everything to do with shellac

- Reactive Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography of Shellac

- Shellac A short introduction to the origin of shellac, the history of Japanning and French polishing, and how to conserve and repair these finishes sympathetically

- Shellac Application By Smith & Rodger