| Part of the Politics series |

| Electoral systems |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

Preferential block voting is a majoritarian voting system for electing several representatives from a multimember constituency, such as a state. Unlike single transferable voting (STV) or list PR, preferential block voting is not a method for obtaining proportional representation, and instead produces similar results to plurality block voting (a type of multiple non-transferable vote, MNTV). Preferential block voting can be seen as a multiple-winner version of instant-runoff, a multiple transferable vote (MTV).

Under both block voting and preferential block voting, a single group of like-minded voters can win every seat, making both forms of block voting non-proportional. Preferential block voting is majoritarian in that each seat is filled by the choice of a majority of voters.

Casting and counting the ballots

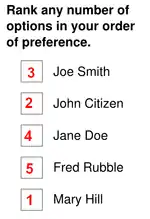

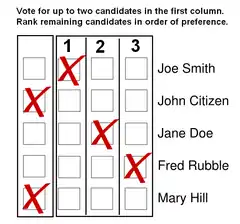

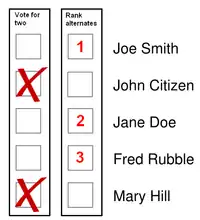

In preferential block voting, a ranked ballot is used, ranking candidates from most to least preferred. Alternate ballot forms may have two groupings of marks, first giving n votes for an n seat election (as in traditional bloc voting), but also allowing the alternate candidates to be ranked in order of preference and used if one or more first choices are eliminated.

Candidates with the smallest tally of first preference votes are eliminated (and their votes transferred as in instant runoff voting) until a candidate has more than half the vote. The count is repeated with the elected candidates removed and all votes returning to full value until the required number of candidates is elected. An example of this method is described in Robert's Rules of Order.[1]

Effects

With or without a preferential element, block voting systems have a number of features which can make them unrepresentative of the diversity of voters' intentions. Block voting regularly produces complete landslide majorities for the group of candidates with the highest level of support. Under preferential block voting, a slate of clones of the first winning candidate are guaranteed to win every available seat.[2] Although less representative, this does tend to lead to greater agreement among those elected.

Use

Block voting was used in the Australian Senate from 1901 to 1948; from 1919, this was preferential block voting.[3] More recently, the system has been used to elect local councils in Australia’s Northern Territory.[4] In elections in 2007 and 2009, Hendersonville, North Carolina used a form of preferential block voting. In 2009, Aspen, Colorado also used a form of preferential block voting for a single election before repealing the system. In 2018, the state of Utah passed a state law creating a pilot program for municipalities to use instant runoff voting for single seat contests and preferential block voting for multi seat contests, and in 2019, Payson, Utah and Vineyard, Utah each held preferential block voting contests for three and two city council seats respectively.[5]

Ballots

| Rank ballot | Hybrid ballots | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Three example ballots for a two-seat election, the first using a pure ranked ballot, and the second using a plurality block voting ballot for the initial vote, and ranking only the alternate preferences. The hybrid ballots are intended to clarify the fact that the top n choices are counted simultaneously, and the ranked choices are used conditionally based on elimination. | ||

See also

- Block approval voting , its approval voting equivalent

- Single transferable vote, its proportional equivalent

- Multiple non-transferable vote, its plurality equivalents

References

- ↑ Robert, Henry M. (2011). Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised, 11th ed., p. 425-428 (RONR)

- ↑ Reilly, Ben; Michael, Maley (2000). "Chapter 3: The Single Transferable Vote and the Alternative Vote Compared". In Bowler, Shaun; Grofman, Bernard (eds.). Elections in Australia, Ireland, and Malta under the Single Transferable Vote: Reflections on an Embedded Institution. University of Michigan Press. pp. 37–58. ISBN 978-0-472-02681-4.

- ↑ Farrell, David M.; McAllister, Ian (2005). "1902 and the Origins of Preferential Electoral Systems in Australia" (PDF). Australian Journal of Politics and History. 51 (2): 155–167. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8497.2005.00368.x. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ↑ Sanders, William (2011). "Alice's Unrepresentative Council: Cause for Intervention?". Australian Journal of Political Science. 46 (4): 699–706. doi:10.1080/10361146.2011.623669. S2CID 154563517. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- ↑ Jack Santucci and Benjamin Reilly, "Utah’s new kind of ranked-choice voting could hurt political minorities — and sometimes even the majority"