The Preventing Sex Trafficking and Strengthening Families Act (H.R. 4980) is a US bill that would address federal adoption incentives and would amend the Social Security Act (SSA) to require the state plan for foster care and adoption assistance to demonstrate that the state agency has developed policies and procedures with respect to the children it is working, and which are (possibly) a victim of sex trafficking or a severe form of trafficking in persons.[1][2] The bill furthermore requires states to implement the 2008 UIFSA version, which is required so the 2007 Hague Maintenance Convention can be ratified by the US.

The bill was introduced into the United States House of Representatives during the 113th United States Congress. The bill is a compromise measure made up of pieces of six other bills.[2]

Background

Adoption

Adoptions in the United States may be either domestic or from another country. Domestic adoptions can be arranged either through adoption agency or independently.[3] Adoption agencies must be licensed by the state in which they operate.[4] The U.S. government maintains a website, Child Welfare Information Gateway, which lists each state's licensed agencies. There are both private and public adoption agencies. Private adoption agencies often focus on infant adoptions, while public adoption agencies typically help find homes for waiting children, many of them presently in foster care and in need of a permanent loving home.[5] To assist in the adoption of waiting children, there is a U.S. government-affiliated website, AdoptUSKids.org, assisting in sharing information about these children with potential adoptive parents.[6] The North American Council on Adoptable Children provides information on financial assistance to adoptive parents (called adoption subsidies) when adopting a child with special needs.[7]

Independent adoptions are usually arranged by attorneys and typically involve newborn children. Approximately 55% of all U.S. newborn adoptions are completed via independent adoption.[8]

The 2000 census was the first census in which adoption statistics were collected. The estimated number of children adopted in the year 2000 was slightly over 128,000, bringing the total U.S. population of adopted children to 2,058,915.[9] In 2008 the number of children adopted increased to nearly 136,000.[10]

Child support

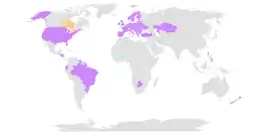

Provisions for recovery of child support are a subject of state-law (rather than federal law) in the US. For the international recovery of child support, bilateral agreements are in place between the US and a number of countries, and certain US States have bilateral agreements with countries in place. In 2007 the Hague Maintenance Convention was adopted within the framework of the Hague Conference on Private International Law, aimed at recovery of international maintenance. The convention requires countries to set up Central Authorities to coordinate recovery of maintenance, and provides for recognition and enforcement measures of judicial maintenance decisions. The US was the first to sign the convention in 2007 and the Senate approved it several years later. Ratification by the US could not take place because domestic legislation needs to be amended. Meanwhile, the agreement has entered into force with respect to the European Union and 5 other European countries: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Norway and Ukraine.

Provisions of the bill

This summary is based largely on the summary provided by the Congressional Research Service, a public domain source.[1]

The Preventing Sex Trafficking and Strengthening Families Act would amend part E (Foster Care and Adoption Assistance) of title IV of the Social Security Act (SSA) to require the state plan for foster care and adoption assistance to demonstrate that the state agency has developed policies and procedures for identifying, documenting in agency records, and determining appropriate services with respect to, any child or youth over whom the state agency has responsibility for placement, care, or supervision who the state has reasonable cause to believe is, or is at risk of being, a victim of sex trafficking or a severe form of trafficking in persons.[1]

The bill would authorize a state, at its option, to identify and document any individual under age 26 without regard to whether the individual is or was in foster care under state responsibility.[1]

The bill would add as state plan requirements: (1) the reporting to law enforcement authorities of instances of sex trafficking, as well as (2) the locating of and responding to children who have run away from foster care.[1]

The bill would include sex trafficking data in the adoption and foster care analysis and reporting system (AFCARS).[1]

The bill would direct the state agency to report immediately information on missing or abducted children or youth to law enforcement authorities for entry into the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.[1]

The bill would require the designated state authority or authorities to: (1) develop a reasonable and prudent parent standard for the child's participation in age or developmentally appropriate extracurricular, enrichment, cultural, and social activities; and (2) apply this standard to any foster family home or child care institution receiving funds under title IV part E.[1]

The bill would direct the Secretary to provide assistance to states on best practices for devising strategies to assist foster parents in applying a reasonable and prudent parent standard in a specified manner.[1]

The bill would make it a purpose of the John H. Chafee Foster Care Independence Program to ensure that children who are likely to remain in foster care until age 18 have regular, ongoing opportunities to engage in age or developmentally-appropriate activities. Authorizes increased appropriations for the program beginning in FY2020.[1]

The bill would limit to children age 16 or older the option, in an initial permanency hearing, of being placed in a planned permanent living arrangement other than a return to home, referral for termination of parental rights, or placement for adoption, with a fit and willing relative (including an adult sibling), or with a legal guardian. Prescribes documentation and determination requirements for such an option.[1]

The bill would give children age 14 and older authority to participate in: (1) the development of their own case plans, in consultation with up to two members of the case planning team; as well as (2) transitional planning for a successful adulthood. Specifies additional requirements for a case plan.[1]

The bill would require the case review system to assure that foster children leaving foster care because of having attained age 18 (or a greater age the state has elected), unless in foster care less than six months, are not discharged without being provided with a copy of their birth certificate, Social Security card, health insurance information, copy of medical records, and a driver's license or equivalent state-issued identification card.[1]

The bill would amend SSA title XI to establish the National Advisory Committee on the Sex Trafficking of Children and Youth in the United States.[1]

The bill would amend SSA title IV part E to extend through FY2016 revise certain requirements for the adoption incentive program, renaming it the adoption and legal guardianship incentive payments program.[1]

The bill would require states to report annually to the Secretary on the calculation and use of savings resulting from the phase-out of eligibility requirements for adoption assistance.[1]

The bill would preserve the eligibility of a child for kinship guardianship assistance payments when a guardian is replaced with a successor guardian.[1]

The bill would require notification of parents of a sibling, where the parent has legal custody of the sibling, when a child is removed from parental custody.[1]

The bill would extend the family connection grant program through FY2014.[1]

The bill would revise requirements for international child support recovery, forming the federal implementation required for ratification of the 2007 Hague Maintenance Convention. The provisions enter into force after a revised version of UIFSA has been passed in all states, and place a penalty on those states that don't do so in the quarter following their next legislative year.[1]

The bill would grant Indian tribes access to the Federal Parent Locator Service (FPLS).[1]

The bill would express the sense of the Congress about the offering of voluntary parenting time arrangements.[1]

The bill would set forth requirements for data exchange standards for improved interoperability.[1]

The bill would amend part D (Child Support and Establishment of Paternity) of SSA title IV to give the employer the option of using electronic transmission methods prescribed by the Secretary for income withholding in the collection and disbursement of child support payments.[1]

Procedural history

The Preventing Sex Trafficking and Strengthening Families Act was introduced into the United States House of Representatives on June 26, 2014, by Rep. Dave Camp (R, MI-4).[11] It was referred to the United States House Committee on Ways and Means and the United States House Committee on the Budget.[11] On July 23, 2014, the House voted to pass the bill in a voice vote.[11]

Debate and discussion

According to Rep. Camp, who sponsored the bill, "we have already seen great progress in increasing adoptions since (the Adoption Incentives program) was created in 1997, and it is our hope to continue this progress with this bill."[2]

The organization First Focus Campaign for Children supported the bill, writing a letter that "urges House leadership to bring this bill to the floor and ensure its swift passage so that vulnerable youth and children can benefit from these important reforms."[12]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 "H.R. 4980 - Summary". United States Congress. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 Kelly, John. "House, Senate Committees Make Deal on Adoption Incentives". The Donaldson Adoption Institute. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ↑ Adopting in America: How To Adopt Within One Year, by Randall Hicks, WordSlinger Press 2005

- ↑ http://www.adoption101.com/agency_adoption.html

- ↑ ADOPTION: The Essential Guide to Adopting Quickly and Safely, by Randall Hicks, Perigee Press 2007

- ↑ "Adopt US Kids". Adoption Exchange Association. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ "Adoption Assistance". 19 January 2017.

- ↑ Independent adoptions

- ↑ https://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/censr-6.pdf

- ↑ "Pubs - Child Welfare Information Gateway" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-01-02. Retrieved 2014-07-24.

- 1 2 3 "H.R. 4980 - All Actions". United States Congress. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ↑ Mathur, Rricha (2 July 2014). "Preventing Sex Trafficking and Strengthening Families Act Endorsement". First Focus Campaign for Children. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

External links

- Library of Congress - Thomas H.R. 4980

- beta.congress.gov H.R. 4980

- GovTrack.us H.R. 4980

- OpenCongress.org H.R. 4980

- WashingtonWatch.com H.R. 4980

- Congressional Budget Office's report on H.R. 4980

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Government.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Government.

.svg.png.webp)