| Propofol infusion syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

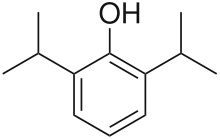

| Propofol |

Propofol infusion syndrome (PRIS) is a rare syndrome which affects patients undergoing long-term treatment with high doses of the anaesthetic and sedative drug propofol. It can lead to cardiac failure, rhabdomyolysis, metabolic acidosis, and kidney failure, and is often fatal.[1][2][3] High blood potassium, high blood triglycerides, and liver enlargement, proposed to be caused by either "a direct mitochondrial respiratory chain inhibition or impaired mitochondrial fatty acid metabolism"[4] are also key features. It is associated with high doses and long-term use of propofol (> 4 mg/kg/h for more than 24 hours). It occurs more commonly in children, and critically ill patients receiving catecholamines and glucocorticoids are at high risk. Treatment is supportive. Early recognition of the syndrome and discontinuation of the propofol infusion reduces morbidity and mortality. Metabolic acidosis is a primary feature and may be the first laboratory evidence of the syndrome.

Presentation

The syndrome clinically presents as acute refractory bradycardia that leads to asystole, in the presence of one or more of the following conditions: metabolic acidosis, rhabdomyolysis, hyperlipidemia, and enlarged liver. The association between PRIS and propofol infusions is generally noted at infusions higher than 4 mg/kg per hour for greater than 48 hours.[4]

Mechanism of Action

The mechanism of action is poorly understood but may involve the impairment of mitochondrial fatty acid metabolism by propofol.[4]

PRIS is a rare complication of propofol infusion. It is generally associated with high doses (>4 mg/kg per hour or >67 mcg/kg per minute) and prolonged use (>48 hours) [5][6][7][8] though it has been reported with high-dose short-term infusions.[9][10]

Additional proposed risk factors include a young age, critical illness, high fat and low carbohydrate intake, inborn errors of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, and concomitant catecholamine infusion or steroid therapy.[9] Characteristics of PRIS include acute refractory bradycardia, severe metabolic acidosis, cardiovascular collapse, rhabdomyolysis, hyperlipidemia, renal failure, and hepatomegaly.[7][11]

The incidence of PRIS is unknown, but it is probably less than 1 percent.[12] Mortality is variable but high (33 to 66 percent).[13][14][7] Treatment involves discontinuation of the propofol infusion and supportive care.[9]

Risk Factors

Predisposing factors seem to include young age, severe critical illness of central nervous system or respiratory origin, exogenous catecholamine or glucocorticoid administration, inadequate carbohydrate intake and subclinical mitochondrial disease.[4]

Treatment

Treatment options are limited and are usually supportive, including hemodialysis with cardiorespiratory support.[4]

References

- ↑ Vasile, Vasile B; Rasulo F; Candiani A; Latronico N. (September 2003). "The pathophysiology of propofol infusion syndrome: a simple name for a complex syndrome". Intensive Care Medicine. 29 (9): 1417–25. doi:10.1007/s00134-003-1905-x. PMID 12904852. S2CID 23932736.

- ↑ Zaccheo, Melissa M; Bucher, Donald H. (June 2008). "Propofol Infusion Syndrome: A Rare Complication With Potentially Fatal Results". Critical Care Nurse. 28 (3): 18–25. doi:10.4037/ccn2008.28.3.18. PMID 18515605.

- ↑ Sharshar, T. (2008). "[ICU-acquired neuromyopathy, delirium and sedation in intensive care unit]". Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 27 (7–8): 617–22. doi:10.1016/j.annfar.2008.05.010. PMID 18584998.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kam, PC; Cardone D. (July 2007). "Propofol infusion syndrome". Anaesthesia. 62 (7): 690–701. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05055.x. PMID 17567345.

- ↑ Hemphill, S; McMenamin, L; Bellamy, MC; Hopkins, PM (April 2019). "Propofol infusion syndrome: a structured literature review and analysis of published case reports". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 122 (4): 448–459. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2018.12.025. PMC 6435842. PMID 30857601.

- ↑ Pothineni, NV; Hayes, K; Deshmukh, A; Paydak, H (March 2015). "Propofol-related infusion syndrome: rare and fatal". American Journal of Therapeutics. 22 (2): e33-5. doi:10.1097/MJT.0b013e318296f165. PMID 23782764.

- 1 2 3 Kam, PC; Cardone, D (July 2007). "Propofol infusion syndrome". Anaesthesia. 62 (7): 690–701. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05055.x. PMID 17567345.

- ↑ McKeage, K; Perry, CM (2003). "Propofol: a review of its use in intensive care sedation of adults". CNS Drugs. 17 (4): 235–72. doi:10.2165/00023210-200317040-00003. PMID 12665397.

- 1 2 3 Diedrich, DA; Brown, DR (March 2011). "Analytic reviews: propofol infusion syndrome in the ICU". Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 26 (2): 59–72. doi:10.1177/0885066610384195. PMID 21464061.

- ↑ Wong, JM (September 2010). "Propofol infusion syndrome". American Journal of Therapeutics. 17 (5): 487–91. doi:10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181ed837a. PMID 20844346.

- ↑ Fong, JJ; Sylvia, L; Ruthazer, R; Schumaker, G; Kcomt, M; Devlin, JW (August 2008). "Predictors of mortality in patients with suspected propofol infusion syndrome". Critical Care Medicine. 36 (8): 2281–7. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e318180c1eb. PMID 18664783. S2CID 13335224.

- ↑ Crozier, TA (December 2006). "The 'propofol infusion syndrome': myth or menace?". European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 23 (12): 987–9. doi:10.1017/s0265021506001189. PMID 17144001.

- ↑ Iyer, VN; Hoel, R; Rabinstein, AA (December 2009). "Propofol infusion syndrome in patients with refractory status epilepticus: an 11-year clinical experience". Critical Care Medicine. 37 (12): 3024–30. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b08ac7. PMID 19661801. S2CID 31199251.

- ↑ Roberts, RJ; Barletta, JF; Fong, JJ; Schumaker, G; Kuper, PJ; Papadopoulos, S; Yogaratnam, D; Kendall, E; Xamplas, R; Gerlach, AT; Szumita, PM; Anger, KE; Arpino, PA; Voils, SA; Grgurich, P; Ruthazer, R; Devlin, JW (2009). "Incidence of propofol-related infusion syndrome in critically ill adults: a prospective, multicenter study". Critical Care. 13 (5): R169. doi:10.1186/cc8145. PMC 2784401. PMID 19874582.