| Part of a series on |

| Paleontology |

|---|

|

|

Paleontology Portal Category |

Pseudofossils are inorganic objects, markings, or impressions that might be mistaken for fossils. Pseudofossils may be misleading, as some types of mineral deposits can mimic lifeforms by forming what appear to be highly detailed or organized structures. One common example is when manganese oxides crystallize with a characteristic treelike or dendritic pattern along a rock fracture. The formation of frost dendrites on a window is another common example of this crystal growth. Concretions are sometimes thought to be fossils, and occasionally one contains a fossil, but are generally not fossils themselves. Chert or flint nodules in limestone can often take forms that resemble fossils.

Background

Pyrite disks or spindles are sometimes mistaken for fossils of sand dollars or other forms (see marcasite). Cracks, bumps, gas bubbles, and such can be difficult to distinguish from true fossils. Specimens that cannot be attributed with certainty to either fossils or pseudofossils are treated as dubiofossils. Debates on whether specific forms are pseudo or true fossils can be lengthy and difficult. For example, Eozoön is a complex laminated form of interlayered calcite and serpentine originally found in Precambrian metamorphosed limestones (marbles). It was at first thought to be the remains of a giant fossil protozoan (Dawson, 1865), then by far the oldest fossil known. Similar structures were subsequently found in metamorphosed limestone blocks ejected during an eruption of Mount Vesuvius. It was clear that high-temperature physical and chemical processes were responsible for the formation of Eozoön in the carbonate rock (O'Brien, 1970). The debate over the interpretation of Eozoon was a significant episode in the history of paleontology (Adelman, 2007).

Chemical gardens can produce branching microtubuli of 2-10 μm in diameter and can resemble very closely the shapes of fossilized primitive fungi or microorganisms. It has been proposed that ancient, precambrian, structures that have been identified as the evidence for the first fungi or even the first life, are more probably products of ancient natural chemical gardens.[1]

Manganese Dendrite (crystal) on a limestone bedding plane from Solnhofen, Germany. Scale in mm.

Manganese Dendrite (crystal) on a limestone bedding plane from Solnhofen, Germany. Scale in mm. Concretion with calcite-filled septarian cracks. Scale in mm.

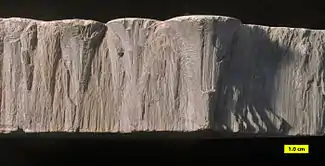

Concretion with calcite-filled septarian cracks. Scale in mm. Eozoön canadense from the Precambrian of Canada, a metamorphic rock made of interlayered calcite and serpentine. A well-known pseudofossil (Adelman, 2007). Scale in mm.

Eozoön canadense from the Precambrian of Canada, a metamorphic rock made of interlayered calcite and serpentine. A well-known pseudofossil (Adelman, 2007). Scale in mm. Cone-in-cone structures produced by compression of limestone. Sometimes mistaken for fossils, thus becoming examples of pseudofossils.

Cone-in-cone structures produced by compression of limestone. Sometimes mistaken for fossils, thus becoming examples of pseudofossils. A marcasite crystal form resembling a sand dollar.

A marcasite crystal form resembling a sand dollar.

Cross-section of a concretion showing layers that resemble tree rings.

Cross-section of a concretion showing layers that resemble tree rings.

References

- ↑ McMahon, Sean (2020). "Earth's earliest and deepest purported fossils may be iron-mineralized chemical gardens". Proc. R. Soc. B. 286 (1916). doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.2410. PMC 6939263.

Bibliography

- Adelman, J. (2007). "Eozoön: debunking the dawn animal". Endeavor. 31 (3): 94–98. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2007.07.002. PMID 17765972.

- Dawson, J. W. (1865). "On the structure of certain organic remains in the Laurentian limestones of Canada". Quart. J. Geol. Soc. 21: 51–59. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1865.021.01-02.12.

- O'Brien, C. F. (1970). "Eozoön canadense "The dawn animal of Canada"". Isis. 61 (2): 206–223. doi:10.1086/350620.

- Spencer, P. K. (1993). "The "coprolites" that aren't: the straight poop on specimens from the Miocene of southwestern Washington State". Ichnos. 2 (3): 1–6. doi:10.1080/10420949309380097.