The gens Pupia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. Members of this gens are mentioned as early as 409 BC, when Publius Pupius was one of the first plebeian quaestors, but over the course of centuries they achieved little of significance, and rarely held any of the higher offices of the Roman state.[1]

Origin

The nomen Pupius seems to be derived from the Latin pupus, a child. From this it seems that the Pupii were Latins, and Chase classifies them among those gentes that either originated at Rome, or cannot be shown to have come from anywhere else.[2]

Praenomina

The Pupii favoured the praenomina Gnaeus, Lucius, and Marcus, all of which were common throughout Roman history. The only other praenomina found among the Pupii occurring in history are Publius, belonging to the first of this family to appear, and Aulus, appearing on coins.

Branches and cognomina

The only cognomen of the Pupii under the Republic is Rufus, red, usually referring to someone with red hair. This surname appears on coins of the Pupii bearing Greek inscriptions. The surname Piso, belonging to Marcus Pupius Piso, consul in 61 BC, was the result of his adoption from the Calpurnia gens.[1]

Members

- This list includes abbreviated praenomina. For an explanation of this practice, see filiation.

- Publius Pupius, elected one of the first plebeian quaestors in 409 BC.[3][4]

- Gnaeus Pupius, one of the duumvirs appointed to begin construction of the Temple of Concord in 217 BC.[5][6]

- Lucius Pupius, aedile in 185 BC, and praetor in 183, was assigned the province of Apulia. He was charged with investigating the celebration of the Bacchanalia, which had recently caused much panic at Rome.[7][8]

- Marcus Pupius M. f., a senator in 129 BC. He was probably the same as the Marcus Pupius who adopted a Calpurnius Piso, since Cicero said he was "extremely old" when he did so.[9][10]

- Marcus Pupius, an old man without living sons, adopted one of the Calpurnii Pisones, who became Marcus Pupius Piso Frugi Calpurnianus.[10]

- Marcus Pupius Piso Frugi Calpurnianus, adopted by the elderly Marcus Pupius, was consul in 61 BC, and reluctantly called for a special court to try Publius Clodius Pulcher for profaning the mysteries of the Bona Dea. During the Civil War, he recruited troops for Gnaeus Pompeius at Delos.[11][12]

- Gnaeus Pupius, a publican representing his comrades in Bithynia, received a recommendation from Cicero to his son-in-law, Furius Crassipes, who was quaestor in Bithynia in 51 BC.[13]

- Lucius Pupius, a primus pilus captured by Caesar at the beginning of the Civil War in 49 BC. Caesar released him unharmed.[14]

- Pupius, a Roman tragedian whose work has been entirely lost. Horace mentions Pupius' "lachrymose poetry" in one of his letters.[15]

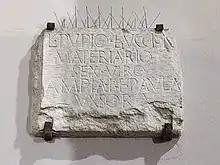

- Aulus Pupius Rufus, known from his coins, appears to have been quaestor in Cyrene.[16]

See also

References

- 1 2 Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, vol. III, p. 605 ("Pupia Gens", "Pupius").

- ↑ Chase, p. 131.

- ↑ Livy, iv. 54.

- ↑ Broughton, vol. I, p. 78 (and note 2).

- ↑ Livy, xxii. 33.

- ↑ Broughton, vol. I, p. 245.

- ↑ Livy, xxxix. 39, 45.

- ↑ Broughton, vol. I, pp. 372, 379.

- ↑ Sherk, "Senatus Consultum De Agro Pergameno", p. 367.

- 1 2 Cicero, De Domo Sua, 13.

- ↑ Josephus, Antiquitates Judaïcae, xiv. 231.

- ↑ Broughton, vol. II, pp. 178, 269.

- ↑ Cicero, Epistulae ad Familiares, xiiil. 9.

- ↑ Caesar, De Bello Civili, i. 13.

- ↑ Horace, Epistulae, i. 1. 67.

- ↑ Eckhel, vol. iv, p. 126.

Bibliography

- Marcus Tullius Cicero, De Domo Sua, Epistulae ad Familiares.

- Gaius Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Civili (Commentaries on the Civil War).

- Quintus Horatius Flaccus (Horace), Epistulae.

- Titus Livius (Livy), History of Rome.

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Romaike Archaiologia.

- Flavius Josephus, Antiquitates Judaïcae (Antiquities of the Jews).

- Lucius Cassius Dio Cocceianus (Cassius Dio), Roman History.

- Joseph Hilarius Eckhel, Doctrina Numorum Veterum (The Study of Ancient Coins, 1792–1798).

- Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, William Smith, ed., Little, Brown and Company, Boston (1849).

- Theodor Mommsen et alii, Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (The Body of Latin Inscriptions, abbreviated CIL), Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften (1853–present).

- George Davis Chase, "The Origin of Roman Praenomina", in Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, vol. VIII (1897).

- T. Robert S. Broughton, The Magistrates of the Roman Republic, American Philological Association (1952).

- Robert K. Sherk, "The Text of the Senatus Consultum De Agro Pergameno", in Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies, vol. 7, pp. 361–369 (1966).