| New York State Route 25 | |

Queens Boulevard near its intersection with Yellowstone Boulevard in Forest Hills | |

| Part of | |

|---|---|

| Owner | City of New York |

| Maintained by | NYCDOT |

| Length | 7.5 mi (12.1 km)[1] |

| Width | 80 to 200 feet (24 to 61 m)[2] |

| Location | Queens, New York City |

| West end | |

| Major junctions | |

| East end | Jamaica Avenue in Jamaica |

Queens Boulevard is a major thoroughfare in the New York City borough of Queens connecting Midtown Manhattan, via the Queensboro Bridge, to Jamaica. It is 7.5 miles (12.1 km) long and forms part of New York State Route 25.

Queens Boulevard runs northwest to southeast from Queens Plaza at the Queensboro Bridge entrance in Long Island City. It runs through the neighborhoods of Sunnyside, Woodside, Elmhurst, Rego Park, Forest Hills, Kew Gardens, and Briarwood before terminating at Jamaica Avenue in Jamaica. The boulevard is 200 feet (61 m) wide for much of its length, with shorter sections between 80 and 150 feet (24 and 46 m) wide. Its immense width, heavy automobile traffic, and thriving commercial scene has historically made it one of the most dangerous thoroughfares in New York City, with pedestrian crossings up to 300 feet (91 m) long at some places.

The route of today's Queens Boulevard originally consisted of Hoffman Boulevard and Thompson Avenue, which was created by linking and expanding these already-existing streets, stubs of which still exist. In 1913, a trolley line was constructed from 59th Street in Manhattan east along the new boulevard. During the 1920s and 1930s the boulevard was widened in conjunction with the digging of the IND Queens Boulevard Line subway tunnels. In 1941, the New York City Planning Department proposed converting Queens Boulevard into a freeway, which ultimately never occurred.

Route description

Queens Boulevard runs northwest to southeast across a little short of half the length of the borough, starting at Queens Plaza at the Queensboro Bridge entrance in Long Island City and running through the neighborhoods of Sunnyside, Woodside, Elmhurst, Rego Park, Forest Hills, Kew Gardens, and Briarwood before terminating at Jamaica Avenue in Jamaica. At 7.5 miles (12.1 km), it is one of the longest roads in Queens, and it runs through some of Queens' busiest areas.[1] Queens Boulevard is the starting point of a number of other major streets in Queens, such as Northern Boulevard, Woodhaven Boulevard, Junction Boulevard, Roosevelt Avenue, and Main Street.[2]

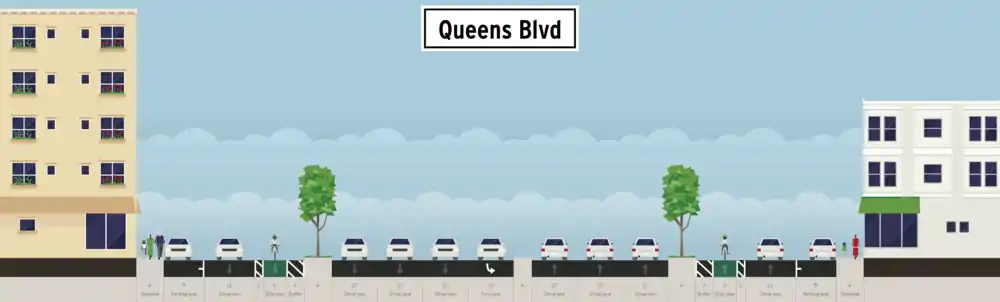

Queens Boulevard has a width of 100 feet (30 m) from Queens Plaza to Van Dam Street, 200 feet (61 m) from Van Dam Street to Union Turnpike, 150 feet (46 m) from Union Turnpike to Hillside Avenue, and 80 feet (24 m) from Hillside Avenue to Jamaica Avenue.[2] Much of the road has 12 lanes, and at its intersection with Yellowstone Boulevard in Forest Hills, it reaches a high point of 16 lanes.[2]

Along much of its length (between Roosevelt Avenue and Union Turnpike), the road includes six express lanes (three in each direction) and a three-lane-wide service road on each side. Drivers must first exit to the service road to make right turns or pull over. Left turns must be made from the express lanes, but only at select cross-streets.[2] The express lanes use a 60-foot-wide (18 m) underpass (separated by a median) to bypass Woodhaven Boulevard and Horace Harding Expressway; the service roads provide access to both streets.[3]

Due to the high number of crashes, Queens Boulevard is known as the Boulevard of Death.[4] More crashes happen along Queens Boulevard than any other roadway statewide.[5][6]

History

Early history

The route of today's Queens Boulevard originally consisted of Hoffman Boulevard and Thompson Avenue,[7] which was created by linking and expanding these already-existing streets, stubs of which still exist. A remnant of the old Hoffman Boulevard can be found in Forest Hills where the local lanes of traffic diverge into two routes, one straight and one that bends around MacDonald Park. The part that bends around the park was the original route of Hoffman Boulevard. The street was built in the early 20th century to connect the new Queensboro Bridge to central Queens, thereby offering an easy outlet from Manhattan.

In 1913, a trolley line was constructed from 59th Street in Manhattan east along the new boulevard.

Widening for subway construction

During the 1920s and 1930s the boulevard was widened in conjunction with the digging of the IND Queens Boulevard Line subway tunnels. The new subway line used cut-and-cover construction and trenches had to be dug up in the center of the thoroughfare, and to allow pedestrians to pass over the construction, temporary bridges were built. The improvement was between Van Dam Street and Hillside Avenue, and it cost $2.23 million. The street was widened to 200 feet (61 m) between Van Dam Street and Union Turnpike, and from there to Hillside Avenue it was widened to 150 feet (46 m). As part of the project, there was to have been separated rights-of-way for the trolley line.[8][9]

On May 2, 1936, Queens Borough President George U. Harvey cut the ribbon for the opening of the center roadway of the Boulevard at Seminole Avenue in Forest Hills. This widened section allowed drivers to access the Grand Central Parkway. This work was partially funded with aid from the Works Progress Administration. $1,555,000 was initially allotted to this project.[10] On April 17, 1937, trolley service along Queens Boulevard ended, being replaced by bus service.[11]

In 1941, the New York City Planning Department proposed converting Queens Boulevard into a freeway, as was done with the Van Wyck Expressway, from the Queensboro Bridge to Hillside Avenue. The boulevard would be converted to an expressway with grade separation at the more important intersections, and by closing off access from minor streets. As part of the project, the express lanes of Queens Boulevard were depressed in the area of Woodhaven Boulevard and Horace Harding Boulevard (later turned into the Long Island Expressway), while the local lanes were kept at grade level. The plan to upgrade the boulevard was delayed with the onset of World War II, and was never completed.[9]

On November 18, 1949, the Traffic Commission approved the retiming of traffic signals along the entire Boulevard to speed traffic, which would take effect about February 1, 1950. The change, known as the "triple-offset system" was expected to reduce peak congestion, like what was done on the Grand Concourse. Westbound traffic would be favored from 7 to 9 a.m., while eastbound traffic would be favored from 5 to 7 p.m.. The Boulevard handled 73,000 cars on an average weekday, with a peak of 7,600 cars an hour towards Manhattan, and a peak of 6,700 to points east.[12]

1960s

In 1960, Queens Borough president John T. Clancy proposed reconstructing the entire seven-mile boulevard to meet traffic demand from the 1964 New York World's Fair for $17.1 million. Due to bureaucratic issues and the need to finance the project using city funds, the project was delayed and cut back to a 2.5 mile section for $2.6 million. Underpasses at Union Turnpike and at Grand Avenue—Broadway were dropped from the plan. On September 3, 1964, the Department of Highways announced that the project was far behind the project's original schedule. Only $2.6 million for the central section of the project was approved as rebuilding more than a mile of the road a time was deemed to be too disruptive for travel. At the time, the rebuilding of the first 1-mile section from 70th Avenue to Union Turnpike was completed.[13]

The six service road loans were resurfaced, yellow asphalt surfacing was installed to guide drivers turning at intersections, and malls were narrowed to widen the roadway and provide space for cars turning off the central six-lane roadway. Work on the 63rd Drive to 70th Avenue section was 70 percent complete, and the Department of Highways expected to request the release of $400,000 for the section to Woodhaven Boulevard within two weeks. Work on that section was expected to start in 1965. Queens Boulevard handled more than 85,000 vehicles a day, making it the second busiest roadway in the city, after the Long Island Expressway, which handled 125,000 vehicles a day.[14]

In 1969, many traffic lights on Queens and Northern Boulevards were computerized, reducing travel time by as much as 25 percent during off-peak hours, and as much as 39 percent during rush hour.[15]

Safety issues and improvements

| Year | Killed |

|---|---|

| 1990 | 18[16] |

| 1991 | 13[16] |

| 1992 | 5[16] |

| 1993 | 17[17] |

| 1997 | 18[17] |

| 2001 | 4 |

| 2002 | 2[18] |

| 2003 | 5 |

| 2004 | 1 |

| 2005 | 2 |

| 2006 | 2 |

| 2007 | 1 |

The combination of Queens Boulevard's immense width, heavy automobile traffic, and thriving commercial scene made it the most dangerous thoroughfare in New York City by the 1990s, and has earned it citywide notoriety and morbid nicknames such as "The Boulevard of Death"[19] and "The Boulevard of Broken Bones".[20] During the period 1950-2000, over 27,000 people were injured on Queens Boulevard. From 2002-04 there were 393 injuries and eight deaths. Queens Boulevard became known as the Boulevard of Death.[21] New York Newsday and the New York Daily News got into a circulation war on the issue of the Boulevard of Death, and the DOT was under pressure to take action. Weinshall implemented pedestrian improvements on Queens Boulevard, including longer pedestrian crossing times, a lowering of the speed limit from 35 mph to 30 mph and the construction of new pedestrian median refuges. The safety improvements have proven successful, without the predicted backups.

Between 1980 and 1984, at least 22 people died and 18 were injured in a 2.5-mile (4.0 km) stretch of Queens Boulevard in Rego Park and Forest Hills.[22][23] From 1993 to 2000, 72 pedestrians were killed trying to cross the street, or an average of 10 per year.[24] Eighteen pedestrians were killed while crossing the boulevard just in 1997. Between 1990 and 2017, it was estimated that 186 people, including 138 pedestrians, died in collisions along Queens Boulevard.[25] The street's design with straight wide lanes has encouraged drivers to drive as if they were on a highway, leading drivers to travel well above the speed limit. In addition, many people cross the Boulevard in areas without crosswalks since there are long stretches between intersections.[16]

Some of the most dangerous crossings of Queens Boulevard are near Roosevelt Avenue, 51st Avenue, Grand Avenue, Woodhaven Boulevard, Yellowstone Boulevard, 71st Avenue, and Union Turnpike; all of these streets either have high vehicular traffic or cross the boulevard diagonally.[26] Pedestrian crossings of Queens Boulevard can be up to 300 feet (91 m) long, or one-and-a-half times the length of a city block in Manhattan.[25] As such, the Boulevard is hard to cross in one traffic light.[16]

1980s and 1990s

In 1985, the New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) started a project to examine the causes of fatalities and injuries on the boulevard.[22] The changing of traffic signals to increase crossing times across the boulevard helped reduce the average pedestrian deaths in a section in Forest Hills and Rego Park from 4 each year from 1980 and 1984 to 1 in 1986. In four of the five years between 1988 and 1992, as many people were killed in car accidents on the boulevard as on any other street in the city.[23] Between 1991 and 1992, new speed limit signs were installed on the Boulevard, police enforcement of traffic light and speeding violations was increased, and the timing for street lights was adjusted.[16]

In 1992, in a test lasting a month, one camera on the Boulevard recorded over 1,000 red-light and speeding violations. In 1993, the NYCDOT planned on installing 15 video cameras across the city that spring, with at least one installed on Queens Boulevard, to monitor and report drivers who run red lights or speed. Summonses would be sent to the owner of the car observed making the traffic infractions. The DOT also planned on installing barriers in the center median separating eastbound and westbound traffic in a section of Forest Hills to discourage people from crossing the street outside of intersections. The DOT had studied installing pedestrian bridges over Queens Boulevard, in addition to Eastern Parkway and Grand Concourse, but had found that it would have been too expensive to do so.[16]

In January 1997, the city commissioned a study of the 2.5 miles (4.0 km) of roadway between the Long Island Expressway and Union Turnpike. The study was completed by 1999, and most work was finished by July 2001.[26]: 138–143 As part of the improvement process, the city installed new curb- and median-extensions along the corridor; repainted crosswalks so they were more visible; added fences in the medians; closed several "slips" that allowed vehicles to make high-speed turns; posted large signs proclaiming that "A Pedestrian Was Killed Crossing Here" at intersections where fatal accidents have occurred; and reduced the speed limit from 35 to 30 miles per hour (56 to 48 km/h); a few segments had 35 mph speed limits. Pedestrian signals were adjusted so that they were given 60 seconds to cross the boulevard, compared to 32-50 seconds before the improvements.[26]: 139–146 [25]

2000s

The street gained notoriety in 2001 as "the Boulevard of Death" due to multiple pedestrian fatalities. Due to an aggressive public safety campaign by the NYCDOT and engineering changes, deaths fell from 17 in 1993 and 18 in 1997 to 4 in 2001; nonfatal accidents were reduced from 2,937 in 1993 to 1,627 in 2001. New fences in the median led most pedestrians to use crosswalks. The number of camera on poles to catch drivers running red lights increase from four to two, and the NYCDOT planned to mount dozens of fake cameras to keep drivers guessing in 2002. The NYCDOT had resisted making the speed for the Boulevard a uniform 30 mph for some time, arguing that it would reduce traffic flow. The NYPD said that a uniform limit would allow them to issue more speeding tickets.[17]

In January 2001, in response to the street safety crisis on the Boulevard, the NYPD began a crackdown on jaywalking, and issued over 6,000 jaywalking summonses on the street, as of June 2001.[27] In May 2001, the NYCDOT proposed eliminating a traffic lane in each direction between Kneeland Avenue and Union Turnpike to be used for metered parking to make the street safer. The arrangement was initially going to be piloted for eight months.[28] Between 1993 and 2000, there were 72 pedestrian boulevards on the Boulevard, with 24 in 1993 and 22 in 1997.[29]

A second phase covering the rest of the boulevard was studied from November 2001 to July 2004, and improvements were finished by late 2006.[26]: 139–146 These improvements decreased pedestrian accidents on the boulevard by 68%, most notably at large and dangerous intersections.[26]: 154 In 2004, one pedestrian was killed crossing Queens Boulevard.[30][31] On April 5, 2004, City officials announced new measures to improve safety on the boulevard. These included additional fences to deter jaywalking, modifications to improve traffic flow and safety, longer crossing times for pedestrians, and the elimination of U-turns and left turns in some locations.[32]

2010s to present: capital improvement

In 2011, safety enhancements, including pedestrian "countdown" signals that count the time left to cross the street, were implemented. That year was the first year that no one was killed crossing the street since 1983, the year when detailed fatality records were first kept.[33] In 2014, the speed limit on Queens Boulevard was reduced further, from 30 mph to 25 mph (40 km/h). The speed limit decrease was part of de Blasio's Vision Zero program, which aimed to decrease pedestrian deaths citywide. From 2014 to 2016, average speeds of eastbound cars on Queens Boulevard declined from 28.7 to 25.6 miles per hour (46.2 to 41.2 km/h), and the speeds of westbound cars declined from 31.5 to 27.3 miles per hour (50.7 to 43.9 km/h).[25]

In 2015, a new initiative was announced to further improve Queens Boulevard at a cost of $100 million.[34] The section between Roosevelt Avenue and 73rd Street received safety improvements, including pedestrian zones and bike lanes, as part of improvement's Phase 1, which began in August 2015 and was finished by the end of the year.[20][35] Phase 2 between 74th Street and Eliot Avenue began in summer 2016.[36][37] Phase 3 was split into two projects: between Eliot Avenue and Yellowstone Boulevard, and between Yellowstone Boulevard and Union Turnpike. The segment of the Phase 3 overhaul between Eliot and Yellowstone started in May 2017,[38] while the segment between Yellowstone and Union Turnpike would start in July 2018.[39]

The project gained opposition from some of the community boards surrounding Queens Boulevard because parking spots were removed to make way for the bike lanes.[39] Starting in 2019,[25] the whole boulevard was to have been totally overhauled in a manner similar to the Grand Concourse's capital reconstruction.[20][35] Partially as a result of these safety improvements, there were no pedestrian deaths on Queens Boulevard between 2014 and 2017.[25] The first segment to be overhauled, between Roosevelt Avenue and 73rd Street, received federal funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in 2023; it is expected to be renovated for $23.75 million between late 2024 and 2027.[40]

Transportation

This street hosts one of the highest numbers of New York City Subway services in the city. The E, F, <F>, and R (IND Queens Boulevard Line) and the 7, <7>, N and W (IRT Flushing Line) all use stretches of the right of way; only Broadway (nine services), Sixth Avenue (seven) in Manhattan and Fulton Street (eight) in Brooklyn carry more at any one time. In addition, the Q60 bus travels its entire length, and the Q32 and Q59 buses travel for significant portions of the boulevard's length.[41]

For a few decades, streetcar service operated along the boulevard, and until 1957 operated along the sides of the Queensboro Bridge into Manhattan.[42][43] For the section where the line ran concurrently with the IRT Flushing Line, the streetcars ran in a median below the viaduct supporting the elevated trains. In the space of the present-day Aviation High School, there was a train yard for the streetcars.[11][44]

Major intersections

The entire route is in Queens County.

| Location | mi[1][45] | km | Destinations | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long Island City | 0.00 | 0.00 | Western terminus; NY 25 continues west | ||

| 0.3 | 0.48 | ||||

| Sunnyside | 1.2 | 1.9 | Greenpoint Avenue west / Roosevelt Avenue east | Western terminus of frontage roads | |

| Woodside | 2.19 | 3.52 | No direct eastbound access to I-278 west; exit 39 on I-278 | ||

| Elmhurst | 3.3 | 5.3 | Grand Avenue | ||

| Rego Park | 3.91 | 6.29 | Grade-separated interchange; exit 19 on I-495 | ||

| Kew Gardens | 6.27 | 10.09 | Eastern terminus of frontage roads; exit 7 on J.R. Parkway | ||

| 6.92 | 11.14 | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance; exit 9 on I-678 | |||

| 7.0 | 11.3 | Main Street north | |||

| Jamaica | 7.4 | 11.9 | NY 25 continues east | ||

| 7.5 | 12.1 | Jamaica Avenue | Eastern terminus | ||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| |||||

References

- 1 2 3 Google (January 14, 2017). "Queens Boulevard" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "NYCityMap". NYC.gov. New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Queens Boulevard Underpass Proves Big Relief to Traffic: Sixty-foot Central Roadway at Woodhaven and Horace Harding Thoroughfares, Built at a Cost of $630,000, Reduces Congestion Another Important Link in Queens Travel Routes". New York Herald Tribune. January 15, 1933. p. B8. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1114616120.

- ↑ Paul Mullins (October 29, 2012). "The boulevard of death: Ghost bikes and spontaneous shrines in New York City". PopAnth.com. Archived from the original on December 27, 2013.

- ↑ "The New York City Pedestrian Safety Study & Action Plan" (PDF). New York City Department of Transportation. August 2010.

- ↑ "Addressing an Elderly Pedestrian Crash Problem in New York City". Center for problem-Oriented Policing.

- ↑ "Town of Newtown, Queens County. Long Island - Woodside". 1873. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

shows Thompson Ave. on south border of map

- ↑ See Flickr album:

- "Office of the President, Borough of Queens, Topographical Bureau Map Showing Roadway Treatment of Queens Boulevard From Van Dam St. To Hillside Ave. In Connection With The Proposed Improvement New York, January 31, 1922". Flickr. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- "Office of the President, Borough of Queens, Topographical Bureau Map Showing Roadway Treatment of Queens Boulevard From Van Dam St. To Hillside Ave. In Connection With The Proposed Improvement New York, January 31, 1922". Flickr. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- "Office of the President, Borough of Queens, Topographical Bureau Map Showing Roadway Treatment of Queens Boulevard From Van Dam St. To Hillside Ave. In Connection With The Proposed Improvement New York, January 31, 1922". Flickr. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- "Office of the President, Borough of Queens, Topographical Bureau Map Showing Roadway Treatment of Queens Boulevard From Van Dam St. To Hillside Ave. In Connection With The Proposed Improvement New York, January 31, 1922". Flickr. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- "Office of the President, Borough of Queens, Topographical Bureau Map Showing Roadway Treatment of Queens Boulevard From Van Dam St. To Hillside Ave. In Connection With The Proposed Improvement New York, January 31, 1922". Flickr. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- "Office of the President, Borough of Queens, Topographical Bureau Map Showing Roadway Treatment of Queens Boulevard From Van Dam St. To Hillside Ave. In Connection With The Proposed Improvement New York, January 31, 1922". Flickr. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- "Office of the President, Borough of Queens, Topographical Bureau Map Showing Roadway Treatment of Queens Boulevard From Van Dam St. To Hillside Ave. In Connection With The Proposed Improvement New York, January 31, 1922". Flickr. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- "Office of the President, Borough of Queens, Topographical Bureau Map Showing Roadway Treatment of Queens Boulevard From Van Dam St. To Hillside Ave. In Connection With The Proposed Improvement New York, January 31, 1922". Flickr. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- "Office of the President, Borough of Queens, Topographical Bureau Map Showing Roadway Treatment of Queens Boulevard From Van Dam St. To Hillside Ave. In Connection With The Proposed Improvement New York, January 31, 1922". Flickr. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- "Office of the President, Borough of Queens, Topographical Bureau Map Showing Roadway Treatment of Queens Boulevard From Van Dam St. To Hillside Ave. In Connection With The Proposed Improvement New York, January 31, 1922". Flickr. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- 1 2 "Queens Boulevard Express Highway (NY 25, unbuilt)". www.nycroads.com. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- ↑ "HARVEY OPENS LANE IN QUEENS BOULEVARD; Cuts Ribbon at Forest Hills, Clearing Way for Traffic to Grand Central Parkway". The New York Times. May 3, 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- 1 2 Meyers, Stephen L. (January 1, 2006). Lost Trolleys of Queens and Long Island. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738545264.

- ↑ "CITY TO SPEED TRAFFIC; Queens Boulevard Lights to Be Retimed in Rush Hours". The New York Times. November 19, 1949. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ "Money Woes Slow Queens Blvd. Job; Far Behind Original Target, Central Section Rebuilding Now Proceeds Smoothly". The New York Times. September 4, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ "Money Woes Slow Queens Blvd. Job; Far Behind Original Target, Central Section Rebuilding Now Proceeds Smoothly". The New York Times. September 4, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ Fosburgh, Lacey (July 27, 1970). "City to Install Computer‐Run Traffic Lights Uptown". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Faison, Seth (January 3, 1993). "Pedestrians at Risk On Queens Boulevard". The New York Times. Retrieved December 28, 2015.

- 1 2 3 O'Grady, Jim (February 24, 2002). "NEIGHBORHOOD REPORT: UPDATE; Despite 'Maniacs,' A Better Report Card For a Troubled Road". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ Santora, Marc (February 3, 2003). "Metro Briefing | New York: Queens: Man Killed By Cab". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ "Boulevard of death' claims another life". WABC Television. April 9, 2009. Archived from the original on March 6, 2010. Retrieved April 10, 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Upcoming Redesign Will Make "Boulevard of Death" Safer, DOT Says". NBC New York. Retrieved October 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Boulevard of Death Claims Another Life". Archived from the original on January 14, 2016. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- 1 2 "Current Trends Queens Boulevard Pedestrian Safety Project -- New York City". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. February 10, 1989. Retrieved October 9, 2015.

- 1 2 Boorstin, Robert O. (March 6, 1987). "Pedestrian Traffic Deaths Show Sharp Decline in New York City". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ "A pedestrian is killed in Queens every 6 weeks on the BOULEVARD OF DEATH". NY Daily News. January 11, 2001.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "No Longer New York City's 'Boulevard of Death'". The New York Times. December 3, 2017. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "SAFE STREETS NYC: Queens" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Transportation. 2007. pp. 136–158. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ↑ Kilgannon, Corey (June 10, 2001). "Kew Gardens Journal; Crossing at Peril of Life and Limb (and a $10 Fine)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ "NEIGHBORHOOD REPORT: QUEENS UP CLOSE; Boulevard Safety Plan: Fewer Lanes, Slower Speeds (Published 2001)". May 20, 2001. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ Kilgannon, Corey; Vasquez, Emily (October 4, 2006). "In Pedestrian's Killing, Queens Couple Sees Another 'Senseless' Statistic". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ "VIOLENT CITY DEATHS HIT HISTORIC LOWS Everything from murders to auto fatalities falls sharply". NY Daily News. January 2, 2005. Retrieved April 10, 2009.

- ↑ "Auto Asphyxiation: Car is King at the DOT". New York Press. March 9, 2004.

- ↑ Worth, Robert F.; Steinhauer, Jennifer (April 6, 2004). "New Traffic Rules for a Dangerous Street". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ "NYC DOT Installs Countdown Signals on Queens Boulevard". nyc.gov. January 24, 2012.

- ↑ Queens Boulevard Safety Improvements, nyc.gov (March 2015)

- 1 2 Fermino, Jennifer (April 1, 2015). "Queens 'Boulevard of Death' to get $100 million renovation to improve safety". NY Daily News. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ Parry, Bill (August 4, 2016). "DOT begins Phase 2 of the Queens Blvd. project in Elmhurst". Times Ledger. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- ↑ Giudice, Anthony (July 28, 2016). "More street safety repairs for Queens Boulevard". www.timesnewsweekly.com. Times Newsweekly. Archived from the original on August 2, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- ↑ Kern-Jedrychowska, Ewa (May 11, 2017). "Board Endorses Queens Boulevard Redesign Despite Loss of 198 Parking Spaces". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on December 13, 2017. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- 1 2 Barca, Christopher (June 2, 2018). "DOT unveils new Qns. Blvd. phase to CB 6". Queens Chronicle. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- ↑ "Queens Boulevard in Woodside to undergo $23.75 million revamp". Sunnyside Post. December 22, 2023. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ "Queens Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. August 2022. Retrieved September 29, 2022.

- ↑ "Queensborough Bridge Railway terminal" Abandoned Stations site

- ↑ Meyers, Stephen L. (May 2008). "Queens of the Thirties". Lost Magazine. No. 24. Archived from the original on May 9, 2012.

- ↑ "Queens Trolleys in the 1930s: Queens Plaza and Queens Blvd." on YouTube

- ↑ "Queens County Inventory Listing" (CSV). New York State Department of Transportation. August 7, 2015. Archived from the original on June 28, 2018. Retrieved September 5, 2017.