| RAF Long Kesh | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maze, Lisburn in Northern Ireland | |||||||||||

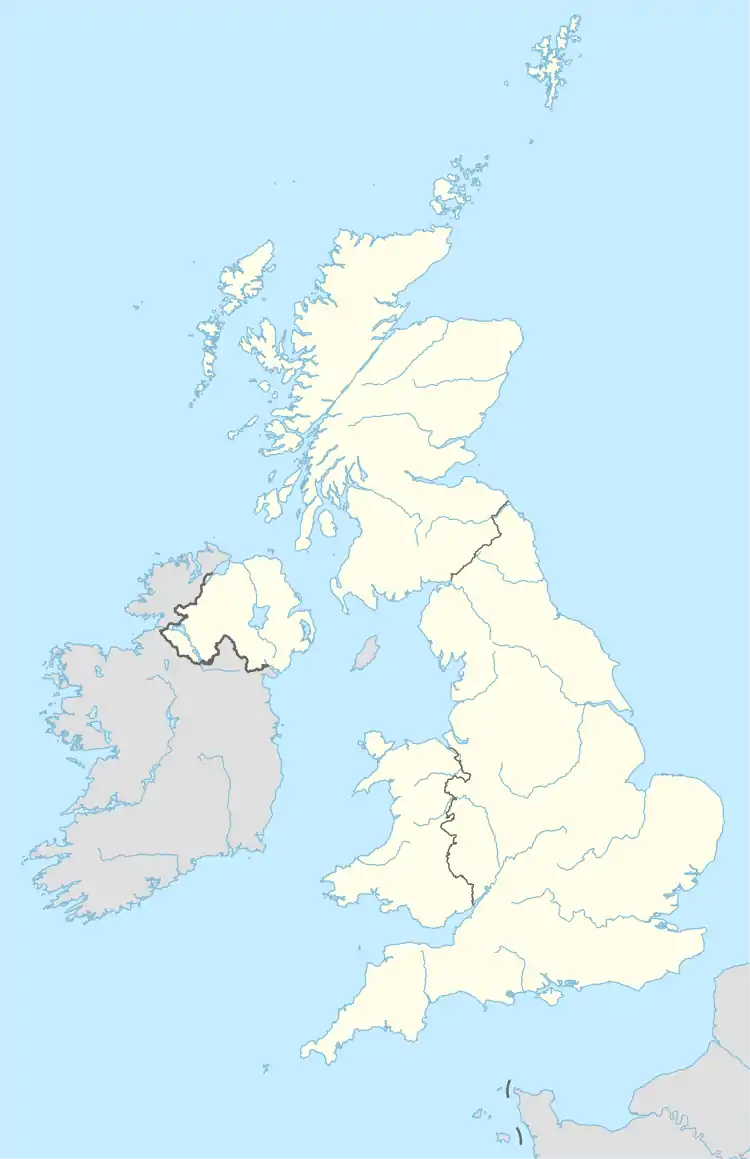

RAF Long Kesh Shown within Northern Ireland  RAF Long Kesh RAF Long Kesh (the United Kingdom) | |||||||||||

| Coordinates | 54°29′22″N 006°06′16″W / 54.48944°N 6.10444°W | ||||||||||

| Type | Royal Air Force station | ||||||||||

| Site information | |||||||||||

| Owner | Air Ministry Admiralty | ||||||||||

| Operator | Royal Air Force Royal Navy | ||||||||||

| Controlled by | RAF Coastal Command Fleet Air Arm | ||||||||||

| Site history | |||||||||||

| Built | 1940-41 | ||||||||||

| In use | 1941-1947 | ||||||||||

| Battles/wars | European theatre of World War II | ||||||||||

| Airfield information | |||||||||||

| Elevation | 35 metres (115 ft) AMSL | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Royal Air Force Long Kesh, or more simply RAF Long Kesh, is a former Royal Air Force station at Maze, Lisburn, Northern Ireland.

Various aircraft operated from the airfield during the Second World War, including the Supermarine Seafire and Spitfire.

History

In 1940–1941, during Second World War, RAF Long Kesh was a primary attack target in "Operation Green", a planned second front to accompany "Operation Sea Lion" for the conquest of the British Isles by Nazi Germany. RAF Long Kesh was to be attacked and wrecked by German airborne forces, whilst Aldergrove, Nutts Corner and Langford Lodge were to be captured.

Hangars were constructed at the airfield by the Ministry of Aircraft Production for the use of Short Brothers to assemble the Short Stirling bomber.[1] Some Stirlings were also built at the site, before their assembly line moved to RAF Maghaberry, the aircraft production facilities at RAF Long Kesh then concentrated on aircraft wing manufacturing. One of the RAF Long Kesh hangars was later used by Miles Aircraft for final assembly and test flying work of the Miles Messenger, which was made at its factory in a linen mill at Banbridge.[1] The hangars are now the home of the Ulster Aviation Society and their collection of military, civil and general aviation aircraft. [2]

Units

- No. 74 Squadron RAF (1942) – Supermarine Spitfire I.[3]

- No. 88 Squadron RAF Detachment (1941-1942) – Douglas Boston III.[4]

- No. 226 Squadron RAF Detachment (1941) – Bristol Blenheim IV.[5]

- No. 231 Squadron RAF (1941-1942) – Curtiss Tomahawk I & IIB.[6]

- No. 290 Squadron RAF (1943-1944) – Miles Martinet.[7]

- No. 422 Squadron RCAF (1942) – Consolidated Catalina IB.[8]

- 800 Naval Air Squadron[9]

- 807 Naval Air Squadron[9]

- 809 Naval Air Squadron[9]

- 838 Naval Air Squadron[9]

- 879 Naval Air Squadron[9]

- 881 Naval Air Squadron[9]

- 882 Naval Air Squadron[9]

- 899 Naval Air Squadron[9]

- Units

- No. 5 (Coastal) Operational Training Unit RAF (December 1942 – April 1944)[10]

- No. 31 Wing RAF (June – December 1941)[11]

- No. 96 Wireless (Observer) Wing RAF (April – May 1942) became No. 96 (Wireless) Wing RAF (May 1942 – ?)[12]

- No. 103 Personnel Dispersal Centre[9]

- No. 201 Gliding School RAF (May 1946 – 1947)[13]

- No. 203 Gliding School RAF (July – September 1955)[13] became No. 671 Volunteer Gliding School RAF (September 1955 – January 1956)[14]

- No. 1494 (Target Towing) Flight RAF (December 1941 – April 1942)[15]

- No. 2774 Squadron RAF Regiment[9]

- RAF Northern Ireland Communication Flight RAF (September – December 1945)[16]

Long Kesh Detention Centre

From August 1971, during The Troubles, the then disused airfield and facilities of RAF Long Kesh became the Long Kesh Detention Centre, where Irish paramilitary suspects were detained by the British government without trial (under the Special Powers Act of 1922) during the Operation Demetrius phase of Operation Banner. In May 1974 Long Kesh housed 747 internees.[17] On 15 October 1974 internees burned 21 of the compounds used to house the internees thereby destroying much of the camp.[18] From 1976 the makeshift structures housing the detainees were replaced by newly constructed "H-Blocks", and the facility was re-designated HM Prison Maze.

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 Ernie Cromie. "Long Kesh & Maghaberry". Ulster Aviation Society.

- ↑ "Directions". Ulster Aviation Society. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ↑ Jefford 1988, p. 47.

- ↑ Jefford 1988, p. 51.

- ↑ Jefford 1988, p. 73.

- ↑ Jefford 1988, p. 74.

- ↑ Jefford 1988, p. 84.

- ↑ Jefford 1988, p. 91.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Long Kesh". Airfields of Britain Conservation Trust. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ↑ Sturtivant, Hamlin & Halley 1997, p. 234.

- ↑ Sturtivant, Hamlin & Halley 1997, p. 314.

- ↑ Sturtivant, Hamlin & Halley 1997, p. 320.

- 1 2 Sturtivant, Hamlin & Halley 1997, p. 168.

- ↑ Sturtivant, Hamlin & Halley 1997, p. 169.

- ↑ Sturtivant, Hamlin & Halley 1997, p. 136.

- ↑ Sturtivant, Hamlin & Halley 1997, p. 228.

- ↑ Mansbach, Richard (1973), Northern Ireland: Half a Century of Partition, Facts on File, Inc, New York, pg 208, ISBN 0-87196-182-2

- ↑ "The burning of Long Kesh". Irish Republican News. RM Distribution. 22 November 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

Bibliography

- Jefford, C.G. RAF Squadrons, a Comprehensive Record of the Movement and Equipment of all RAF Squadrons and their Antecedents since 1912. Shrewsbury, Shropshire, UK: Airlife Publishing, 1988. ISBN 1-84037-141-2.

- Sturtivant, R; Hamlin, J; Halley, J (1997). Royal Air Force flying training and support units. UK: Air-Britain (Historians). ISBN 0-85130-252-1.