| Race |

|---|

| History |

| Society |

| Race and... |

| By location |

| Related topics |

|

Miscegenation (/mɪˌsɛdʒəˈneɪʃən/ miss-EJ-ə-NAY-shən) is marriage or admixture between people who are considered to be members of different races.[1] The word, now usually considered pejorative, is derived from a combination of the Latin terms miscere ('to mix') and genus ('race' or 'kind').[2] The word first appeared in Miscegenation: The Theory of the Blending of the Races, Applied to the American White Man and Negro, a hoax anti-abolitionist pamphlet David Goodman Croly and others published anonymously in advance of the 1864 presidential election in the United States.[2][3] The term came to be associated with laws that banned interracial marriage and sex, which were known as anti-miscegenation laws.[4]

Although the term "miscegenation" was formed from the Latin for "mixing races/kinds", and it could therefore be perceived as being value-neutral, it is almost always a pejorative term which is used by people who believe in racial superiority or purity,[5] and possibly intended to be negative in the erroneous belief that it derives from the prefix mis-. Less loaded terms for multiethnic relationships, such as interethnic or interracial marriage, and mixed-race, multiethnic, or multiracial people, are more common in contemporary usage.

Usage

In the present day, the use of the word miscegenation is avoided by many scholars because the term suggests that race is a concrete biological phenomenon, rather than a categorization which is imposed on certain relationships. The term's historical usage in contexts which typically implied disapproval is also a reason why more unambiguously neutral terms such as interracial, interethnic or cross-cultural are more common in contemporary usage.[6] The term remains in use among scholars when referring to past practices concerning multiraciality, such as anti-miscegenation laws that banned interracial marriages.[7]

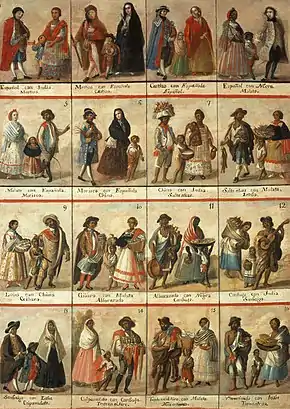

In Spanish, Portuguese, and French, the words used to describe the mixing of races are mestizaje, mestiçagem, and métissage. These words, much older than the term miscegenation, are derived from the Late Latin mixticius for "mixed", which is also the root of the Spanish word mestizo. (Portuguese also uses miscigenação, derived from the same Latin root as the English word.) These non-English terms for "race-mixing" are not considered as offensive as "miscegenation", although they have historically been tied to the caste system (casta) that was established during the colonial era in Spanish-speaking Latin America.

Today, the mixes among races and ethnicities are diverse, so it is considered preferable to use the term "mixed-race" or simply "mixed" (mezcla). In Portuguese-speaking Latin America (i.e., Brazil), a milder form of caste system existed, although it also provided for legal and social discrimination among individuals belonging to different races, since slavery for black people existed until the late 19th century. Intermarriage occurred significantly from the very first settlements to the present day, affording mixed people upward mobility in Brazil for Black Brazilians, a phenomenon known as the "mulatto escape hatch".[8] To this day, there are controversies if Brazilian class system would be drawn mostly around socioeconomic lines, not racial ones (in a manner similar to other former Portuguese colonies). Conversely, people classified in censuses as black, brown ("pardo") or indigenous have disadvantaged social indicators in comparison to the white population.[9][10]

The concept of miscegenation is tied to concepts of racial difference. As the different connotations and etymologies of miscegenation and mestizaje suggest, definitions of race, "race mixing" and multiraciality have diverged globally as well as historically, depending on changing social circumstances and cultural perceptions. Mestizo are people of mixed white and indigenous, usually Amerindian ancestry, who do not self-identify as indigenous peoples or Native Americans. In Canada, however, the Métis, who also have partly Amerindian and partly white, often French Canadian, ancestry, have identified as an ethnic group and are a constitutionally recognized aboriginal people.

Interracial marriages are often disparaged in racial minority communities as well.[11] Data from the Pew Research Center has shown that African Americans are twice as likely as white Americans to believe that interracial marriage "is a bad thing".[12] There is a considerable amount of scientific literature that demonstrates similar patterns.[13][14]

The differences between related terms and words which encompass aspects of racial admixture show the impact of different historical and cultural factors leading to changing social interpretations of race and ethnicity. Thus the Comte de Montlosier, in exile during the French Revolution, the equated class difference in 18th-century France with racial difference. Borrowing Boulainvilliers' discourse on the "Nordic race" as being the French aristocracy that invaded the plebeian "Gauls", he showed his contempt for the lowest social class, the Third Estate, calling it "this new person born of slaves ... a mixture of all races and of all times".

Etymological history

Miscegenation comes from the Latin miscere, 'to mix' and genus, 'kind'.[15] The word was coined in the U.S. in 1863 in an anonymous hoax pamphlet, and the etymology of the word is tied up with political conflicts during the American Civil War over the abolition of slavery and over the racial segregation of African Americans. The reference to genus was made to emphasize the supposedly distinct biological differences between whites and non-whites, though all humans belong to the same genus, Homo, and the same species, Homo sapiens.

The word was coined in an anonymous propaganda pamphlet published in New York City in December 1863, during the American Civil War. The pamphlet was entitled Miscegenation: The Theory of the Blending of the Races, Applied to the American White Man and Negro.[16] It purported to advocate the intermarriage of whites and blacks until they were indistinguishably mixed, as desirable, and further asserted that this was a goal of the Republican Party. The pamphlet was a hoax, concocted by Democrats to discredit the Republicans by imputing to them what were then radical views that would offend the vast majority of whites, even those who opposed slavery. The issue of miscegenation, raised by the opponents of Abraham Lincoln, featured prominently in the election campaign of 1864. In his fourth debate with Stephen A. Douglas, Lincoln took great care to emphasise that he supported the law of Illinois which forbade "the marrying of white people with negroes".[17]

The pamphlet and variations on it were reprinted widely in both the North and South by Democrats and Confederates. Only in November 1864, after Lincoln had won the election, was the pamphlet exposed in the United States as a hoax. It was written by David Goodman Croly, managing editor of the New York World, a Democratic Party paper, and George Wakeman, a World reporter. By then, the word miscegenation had entered the common language of the day as a popular buzzword in political and social discourse.

Before the publication of Miscegenation, the words racial intermixing and amalgamation were used as general terms for ethnic and racial genetic mixing. Contemporary usage of the amalgamation metaphor, borrowed from metallurgy, was that of Ralph Waldo Emerson's private vision in 1845 of America as an ethnic and racial smelting-pot, a variation on the concept of the melting pot.[18] Opinions in the U.S. on the desirability of such intermixing, including that between white Protestants and Irish Catholic immigrants, were divided. The term miscegenation was coined to refer specifically to the intermarriage of blacks and whites, with the intent of galvanizing opposition to the war.

In Spanish America, the term mestizaje, which is derived from mestizo, a term used to describe a person who is the offspring of an Indigenous American and a European. The primary reason why there are so few indigenous peoples of Central and South America remaining is because of the persistent and pervasive miscegenation between the Iberian colonists and the indigenous American population, which is the most common admixture of ethnicities found in the genetic tests of present-day Latinos.[19][20] This explains why Latinos in North America, the vast majority of whom are immigrants or descendants of immigrants from Central and South America, carry an average of 18% Native American ancestry, and 65.1% European ancestry (mostly from the Iberian Peninsula).[21][22]

Laws banning miscegenation

Laws banning "race-mixing" were enforced in certain U.S. states until 1967 (but they were still on the books in some states until 2000),[23] in Nazi Germany (the Nuremberg Laws) from 1935 until 1945, and in South Africa during the apartheid era (1949–1985). All of these laws primarily banned marriage between persons who were members of different racially or ethnically defined groups, which was termed "amalgamation" or "miscegenation" in the U.S. The laws in Nazi Germany and the laws in many U.S. states, as well as the laws in South Africa, also banned sexual relations between such individuals.

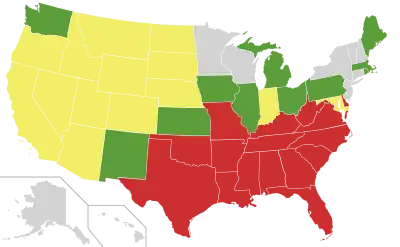

In the United States, various state laws prohibited marriages between whites and blacks, and in many states, they also prohibited marriages between whites and Native Americans as well as marriages between whites and Asians.[24] In the U.S., such laws were known as anti-miscegenation laws. From 1913 until 1948, 30 out of the then 48 states enforced such laws.[25] Although an "Anti-Miscegenation Amendment" to the United States Constitution was proposed in 1871, in 1912–1913, and again in 1928,[26][27] no nationwide law against racially mixed marriages was ever enacted. In 1967, the United States Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Loving v. Virginia that anti-miscegenation laws are unconstitutional. With this ruling, these laws were no longer in effect in the remaining 16 states which still had them.

The Nazi ban on interracial sexual relations and marriages was enacted in September 1935 as part of the Nuremberg Laws, the Gesetz zum Schutze des deutschen Blutes und der deutschen Ehre (The Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour). The Nuremberg Laws classified Jews as a race, and they also forbade extramarital sexual relations and marriages between persons who were classified as "Aryans" and persons who were classified as "non-Aryans". Violations of these laws were condemned as Rassenschande (lit. "race-disgrace/race-shame") and they could be punished by imprisonment (usually followed by deportation to a concentration camp) and they could even be punished by death.

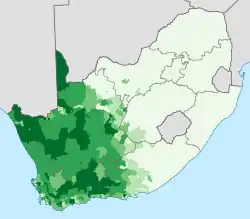

The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act in South Africa, enacted in 1949, banned intermarriages between members of different racial groups, including intermarriages between whites and non-whites. The Immorality Act, enacted in 1950, also made it a criminal offense for a white person to have any sexual relations with a person who was a member of a different race. Both of these laws were repealed in 1985.

History of ethnoracial admixture and attitudes towards miscegenation

Africa

Africa has had a long history of mixing with non-Africans since prehistoric times. The Eurasian backflow, which happened in prehistoric times, saw a huge migration from the Levant entering the region and these migrants mixing with the native Africans. Signs of this migration can be found among the people inhabiting the Horn of Africa and Sudan.[28] Africa in antiquity, also has had long history of interracial mixing with male Arab and European explorers, traders and soldiers having sexual relations with black African women as well as taking them as wives.[29]

Sir Richard Francis Burton writes, during his expedition to Africa, about relationships between black women and white men: "The women are well disposed toward strangers of fair complexion, apparently with the permission of their husbands." There are several mixed race populations throughout Africa mostly the results of interracial relationships between Arab and European men and black women. In South Africa, there are big mixed race communities like the Coloureds and Griqua formed by White colonists taking native African wives. In Namibia there is a community called the Rehoboth Basters formed by the interracial marriage of Dutch/German men and black African women.

In the former Portuguese Africa (now known as Angola, Mozambique and Cape Verde) racial mixing between white Portuguese and black Africans was fairly common, especially in Cape Verde where the majority of the population is of mixed descent.

There have been some recorded cases of Chinese merchants and labourers taking African wives throughout Africa as many Chinese workers were employed to build railways and other infrastructural projects in Africa. These labour groups were made up completely of men with very few Chinese women coming to Africa.

In West Africa, especially Nigeria there are many cases of non-African men taking African women. Many of their offspring have gained prominent positions in Africa. Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings, who had a Scottish father and a black Ghanaian mother became the president of Ghana. Jean Ping, the son of a Chinese trader and a black Gabonese mother, became the deputy prime minister as well as the foreign minister of Gabon and was the Chairperson of the Commission of the African Union from 2009 to 2012. The president of Botswana, Ian Khama, is the son of Botswana's first president, Seretse Khama, and a white British student, Ruth Williams Khama. Nicolas Grunitzky, who was the son of a white German father and a Togolese mother, became the second president of Togo after a coup.

Indian men, who have long been traders in East Africa, sometimes married among local African women. The British Empire brought many Indian workers into East Africa to build the Uganda Railway. Indians eventually populated South Africa, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Malawi, Rwanda, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Zaire in small numbers. These interracial unions were mostly unilateral marriages between Indian men and East African women.[30]

Many Chinese men working in Africa have married Black African women in Angola, South Africa, Gabon, Tanzania, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Lagos in Nigeria, Congo & Ethiopia and fathered children with them.[31][32]

Ghana

Many Chinese men who engaged in gold mining in Ghana married local Black African Ghanaian women and had children with them and then the Ghana government deported illegal miners, leaving the mixed race Chinese fathered children stranded in Ghana while their fathers were sent back to China.[33][34]

Kenya

Early Chinese mariners had a variety of contacts with Kenya. Archaeologists have found Chinese porcelains made during the Tang dynasty (618–907) in Kenyan villages; however, these were believed to have been brought over by Zheng He during his 15th century ocean voyages.[35] On Lamu Island off the Kenyan coast, local oral tradition maintains that 20 shipwrecked Chinese sailors with 400 survivors,[36] possibly part of Zheng's fleet, washed up on shore there hundreds of years ago. Given permission to settle by local tribes after having killed a dangerous python, they converted to Islam and married local women. Now, they are believed to have just six descendants left there; in 2002, DNA tests conducted on one of the women confirmed that she was of Chinese descent. Her daughter, Mwamaka Sharifu, later received a PRC government scholarship to study traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in China.[37][38][39]

On Pate Island, Frank Viviano described in a July 2005 National Geographic article how ceramic fragments had been found around Lamu which the administrative officer of the local Swahili history museum claimed were of Chinese origin, specifically from Zheng He's voyage to east Africa. The eyes of the Pate people resembled Chinese and Famao and Wei were some of the names among them which were speculated to be of Chinese origin. Their ancestors were said to be from indigenous women who intermarried with Chinese Ming sailors when they were shipwrecked. Two places on Pate were called "Old Shanga", and "New Shanga", which the Chinese sailors had named. A local guide who claimed descent from the Chinese showed Frank a graveyard made out of coral on the island, indicating that they were the graves of the Chinese sailors, which the author described as "virtually identical" to Chinese Ming dynasty tombs, complete with "half-moon domes" and "terraced entries".[40]

New interest in Kenya's natural resources has attracted over $1 billion of investment from Chinese firms. This has propelled new development in Kenya's infrastructure with Chinese firms bringing in their own male workers to build roads.[41] The temporary residents usually arrive without their spouses and families. Thus, a rise of incidents involving local college-aged females has resulted in an increased rate of Afro-Chinese infant births to single Kenyan mothers.[42]

In Kenya there is a trend of the following influx of Chinese male workers in Kenya with a growing number of abandoned babies of Chinese men who fathered children with local women, causing concern.[43][44]

Nigeria

A Chinese man abandoned his Nigerian Ogun girlfriend Tope Samuel with their child in Ogun state.[45][46]

Uganda

The topic of mixed race Ugandans continues to resurface, in the public arena, with the growing number of multiracial Ugandans (Multiracial Ugandans in Uganda).

Many Ugandan women have been marrying Chinese businessmen who moved to Uganda and reproducing with them.[47]

Mauritius

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Chinese men in Mauritius married local Indian and Creole women due to both the lack of Chinese women, and the higher numbers of Indian women on the island.[48][49] When the very first Chinese men arrived in Mauritius, they were reluctant to marry local women due to their customary endogamy rules. But with no Chinese women in sight, the Chinese men eventually began to integrate themselves and mix with the local Creole and Indian populations on the island and establish households en ménage.[50] The 1921 census in Mauritius counted that Indian women there had a total of 148 children fathered by Chinese men.[51][52][53] These Chinese were mostly traders.[54]

Congo

During the 1970s, an increased demand for copper and cobalt attracted Japanese investments in the mineral-rich southeastern region of Katanga Province. Over a 10-year period, more than 1,000 Japanese miners relocated to the region, confined to a strictly male-only camp. Arriving without family or spouses, the men often sought social interaction outside the confines of their camps. In search of intimacy with the opposite sex, resulting in cohabitation, the men openly engaged in interracial dating and relationships, a practice embraced by the local society. As a result, a number of Japanese miners fathered children with Native Congolese women. However, most of the mixed race infants resulting from these unions died, soon after birth. Multiple testimonies of local people suggest that the infants were poisoned by a Japanese lead physician and nurse working at the local mining hospital. Subsequently, the circumstances would have brought the miners shame as most of them already had families back in their native Japan. The practice forced many native Katangan mothers to hide their children by not reporting to the hospital to give birth.

Today, fifty Afro-Japanese have formed an association of Katanga Infanticide survivors. The organization has hired legal counsel seeking a formal investigation into the killings. The group submitted an official inquiry to both the Congolese and Japanese governments, to no avail. Issues specific to this group include having no documentation of their births since not having been born in the local hospital spared their lives. The total number of survivors is unknown. [55]

Réunion

The majority of the population of Réunion is defined as mixed race. In the last 350 years, various ethnic groups (Africans, Chinese, English, French, Gujarati Indians, Tamil Indians) have arrived and settled on the island. There have been mixed race people on the island since its first permanent inhabitation in 1665. The native Kaf population has a diverse range of ancestry stemming from colonial Indian and Chinese peoples. They also descend from African slaves brought from countries like Mozambique, Guinea, Senegal, Madagascar, Tanzania, and Zambia to the island.

There have been several cases of Chinese merchants and laborers marrying black African women as many Chinese workers were employed to build railways and other infrastructural projects in Africa. These labour groups were made up completely of men with very few Chinese women coming to Africa. In Réunion and Madagascar, intermarriage between Chinese men of Cantonese origin and African women is not uncommon.[56]

Most population of Réunion Creoles who are of mixed ancestry and make up the majority of the population. Mixed unions between European men and Chinese men with African women, Indian women, Chinese women, Madagascar women were also common. In 2005, a genetic study on the racially mixed people of Réunion found the following. For maternal (mitochondrial) DNA, the haplogroups are Indian (44%), East Asian (27%), European/Middle Eastern (19%) or African (10%). The Indian lineages are M2, M6 and U2i, the East Asian ones are E1, D5a, M7c, and F (E1 and M7c also found only in South East Asia and in Madagascar), the European/Middle Eastern ones are U2e, T1, J, H, and I, and the African ones are L1b1, L2a1, L3b, and L3e1.[57]

For paternal (Y-chromosome) DNA, the haplogroups are European/Middle Eastern (85%) or East Asian (15%). The European lineages are R1b and I, the Middle Eastern one E1b1b1c (formerly E3b3) (also found in Northeast Africa), and the East Asian ones are R1a (found in many parts of the world including Europe and Central and Southern Asia but the particular sequence has been found in Asia) and O3.[57]

Madagascar

There was frequent intermixing between the Austronesian and Bantu-speaking populations of Madagascar. A large number of the Malagasy today are the result of admixture between Austronesians and Africans. This is most evident in the Mikea, who are also the last known Malagasy population to still practice a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. In the study of "The Dual Origin of the Malagasy in Island Southeast Asia and East Africa: Evidence from Maternal and Paternal Lineages" shows the Bantu maternal origin to be 38% and Paternal 51% while the Southeast Asian paternal to be 34% and maternal 62%.[58][59][60] In the study of Malagasy, autosomal DNA shows the highlanders ethnic group like Merina are almost an even mixture of Southeast Asian and Bantu origin, while the coastal ethnic group have much higher Bantu mixture in their autosomal DNA suggesting they are mixture of new Bantu migrants and the already established highlander ethnic group. Maximum-likelihood estimates favour a scenario in which Madagascar was settled approximately 1200 years ago by a very small group of women of approximately 30.[61] The Malagasy people existed through intermarriages between the small founding population.

Intermarriage between Chinese men and native Malagasy women was not uncommon.[56] Several thousand Cantonese men intermarried and cohabited with Malagasy women. 98% of the Chinese traced their origin from Guangdong – more specifically, the Cantonese district of Shunde. For example, the 1954 census found 1,111 "irregular" Chinese-Malagasy unions and 125 legitimate, i.e., legally married. Children were registered by their mothers under a Malagasy name. Intermarriage between French men and Native Malagasy women was not uncommon either.

North America

Canada

Canada had no explicit laws against mixed marriage, but anti-miscegenation was often enforced through different laws and upheld by the Supreme Court of Canada as valid. Velma Demerson, for example, was imprisoned in 1939 for carrying the child of a Chinese father; she was deemed "incorrigible" under the Female Refuges Act, and was physically experimented on in prison to discover the causes of her behaviour.[62]

Ultimately, an informal and extra-legal regime ensured that the social taboo of racial intermixing was kept to a minimum (Walker, 1997; Backhouse, 1999; Walker, 2000). And, from 1855 until the 1960s, Canada chose its immigrants on the basis of their racial categorization rather than the individual merits of the applicant, with preference being given to immigrants of Northern European (especially British, Scandinavian and French) origin over the so-called "black and Asiatic races", and at times over central and southern European races.

It is arguable that Canada's various manifestations of the federal Indian Act were designed to regulate interracial (in this circumstance, Aboriginal and non- Aboriginal) marital relations and the categorization of mixed-race offspring.

The Canadian Ku Klux Klan burned crosses at a gathering in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, to discourage mixed marriages, and in 1930 were enlisted in Oakville, Ontario, to intimidate Isabella Jones and Ira Junius Johnson out of marrying.

United States

The historical taboo surrounding white–black relationships among American whites can be seen as a historical consequence of the oppression and racial segregation of African Americans.[63][64] In many U.S. states, interracial marriage was already illegal when the term miscegenation was coined in 1863. (Before that, it was called "amalgamation".) The first laws banning interracial marriage were introduced in the late 17th century in the slave-holding colonies of Virginia (1691) and Maryland (1692). Later these laws also spread to colonies and states where slavery did not exist.

Although vehemently opposed to miscegenation in public, Thomas Jefferson fathered his slave Sally Hemings child.[65] Regarding blacks as "inferior to the whites in the endowments of both body and mind", Jefferson, in his Notes on the State of Virginia published in 1785, would also write: "The improvement of the blacks in body and mind, in the first instance of their mixture with the whites, has been observed by every one, and proves that their inferiority is not the effect merely of their condition of life".[66]

In the early nineteenth century, the Quaker planter Zephaniah Kingsley published a pamphlet, which defended miscegenation, the pamphlet was reprinted three times. According to him, mixed-race children are healthier and more beautiful. He also claimed to be married to a slave who he bought in Cuba at the age of 13, though the marriage did not take place in the United States, and there is no evidence of it other than Kingsley's statement. He was eventually forced to leave the United States and move to the Mayorasgo de Koka plantation in Haiti (now Dominican Republic).

In 1918, there was considerable controversy in Arizona when an Asian-Indian farmer B. K. Singh married the sixteen-year-old daughter of one of his white tenants.[67] During and after slavery, most American whites regarded interracial marriage between whites and blacks as taboo. However, during slavery, many white American men and women did conceive children with black partners. Some children were freed by their slave-holding fathers or bought to be emancipated if the father was not the owner. Most mixed-raced descendants merged into the African-American ethnic group during the Jim Crow era.

Initially, Filipino Americans were considered white and were not barred from interracial marriage, with documented instances of interracial marriage of Filipino men and White women in Louisiana and Washington, D.C. However, by the late 19th century and early 20th century in California, Filipinos were barred from marrying white women through a series of court cases that redefined their racial interpretation under the law. During World War II, Filipino servicemen in California had to travel with their White fiancees to New Mexico, to be able to marry.[68]

After the Civil War and the abolition of slavery in 1865, the marriage of white and black Americans continued to be taboo, particularly in the former slave states.

The Motion Picture Production Code of 1930, also known as Hays Code, explicitly stated that the depiction of "miscegenation ... is forbidden".[69] One important strategy intended to discourage the marriage of white Americans and Americans of partly African descent was the promulgation of the one-drop theory, which held that any person with any known African ancestry, however remote, must be regarded as black. This definition of blackness was encoded in the anti-miscegenation laws of various U.S. states, such as Virginia's Racial Integrity Act of 1924. The plaintiffs in Loving v. Virginia, Mildred Jeter and Richard Loving became the historically most prominent interracial couple in the US through their legal struggle against this act.

Throughout American history, there has been frequent mixing between Native Americans and black Africans. When Native Americans invaded the European colony of Jamestown, Virginia in 1622, they killed the Europeans but took the African slaves as captives, gradually integrating them. Interracial relationships occurred between African Americans and members of other tribes along coastal states. During the transitional period of Africans becoming the primary race enslaved, Native Americans were sometimes enslaved with them. Africans and Native Americans worked together, some even intermarried and had mixed children. The relationship between Africans and Native-Americans was seen as a threat to Europeans and European-Americans, who actively tried to divide Native-Americans and Africans and put them against each other.[71]

During the 18th Century, some Native American women turned to freed or runaway African men due to a major decline in the male population in Native American villages. At the same time, the early slave population in America was disproportionately male. Records show that some Native American women bought African men as slaves. Unknown to European sellers, the women freed and married the men into their tribe. Some African men chose Native American women as their partners because their children would be free, as the child's status followed that of the mother. The men could marry into some of the matrilineal tribes and be accepted, as their children were still considered to belong to the mother's people. As European expansion increased in the Southeast, African and Native American marriages became more numerous.[72]

From the mid 19th to the mid 20th century, many black people and ethnic Mexicans intermarried with each other in the Lower Rio Grande Valley in South Texas (mostly in Cameron County and Hidalgo County). In Cameron County, 38% of black people were interracially married (7/18 families) while in Hidalgo County the number was 72% (18/25 families). These two counties had the highest rates of interracial marriages involving at least one black spouse in the United States. The vast majority of these marriages involved black men marrying ethnic Mexican women or first generation Tejanas (Texas-born women of Mexican descent). Since ethnic Mexicans were considered white by Texas officials and the U.S. government, such marriages were a violation of the state's anti-miscegenation laws. Yet, there is no evidence that anyone in South Texas was prosecuted for violating this law. The rates of this interracial marriage dynamic can be traced back to when black men moved into the Lower Rio Grande Valley after the Civil War ended. They married into ethnic Mexican families and joined other black people who found sanctuary on the U.S./Mexico border.[73]

From the mid 19th century to the 20th century, the several hundred thousand Chinese men who migrated were almost entirely of Cantonese origin, mostly from Taishan. Anti-miscegenation laws prohibited Chinese men from marrying white women in many states.[74] After the Emancipation Proclamation, many intermarriages in some states were not recorded and historically, Chinese American men married African American women in proportions that were higher than their total marriage numbers due to the fact that few Chinese American women lived in the United States. After the Emancipation Proclamation, many Chinese Americans migrated to the Southern United States, particularly to Arkansas, to work on plantations. For example, in 1880, the tenth US Census of Louisiana alone noted 57% of all interracial marriages were between Chinese men and black women and 43% of them were between Chinese men and white women.[75] Between 20 and 30 percent of the Chinese who lived in Mississippi married black women before 1940.[76] In a genetic study of 199 samples from African American males found one belong to haplogroup O2a ( or 0.5% )[77] It was discovered by historian Henry Louis Gates, Jr in the African American Lives documentary miniseries that NASA astronaut Mae Jemison has a significant (above 10%) genetic East Asian admixture. Gates speculated that the intermarriage/relations between migrant Chinese workers and black, or African-American slaves or ex-slaves during the 19th century might have contributed to her ethnic and genetic make-up. In the mid 1850s, 70 to 150 Chinese were living in New York City and 11 of them married Irish women. In 1906 the New York Times (6 August) reported that 300 white women (Irish American) were married to Chinese men in New York, with many more cohabiting. In 1900, based on Liang's research, of the 120,000 men in more than 20 Chinese communities in the United States, he estimated that one out of every twenty Chinese men (Cantonese) was married to a white woman.[78] In the 1960s census showed 3500 Chinese men married to white women and 2900 Chinese women married to white men.[79]

Before the Civil War, accusations of support for miscegenation were commonly made against Abolitionists by defenders of slavery. After the war, similar charges were made against advocates of equal rights for African Americans by white segregationists. According to these accusations, they were said to be secretly plotting the destruction of the white race through the promotion of miscegenation. In the 1950s, segregationists alleged that a Communist plot to promote miscegenation in order to hasten the takeover of the United States was being funded by the government of the Soviet Union. In 1957, segregationists cited the anti-semitic hoax A Racial Program for the Twentieth Century as a source of evidence which proved the supposed validity of these claims.

Anti-amalgamation cartoons, such as those which were published by Edward William Clay, were "elaborately exaggerated anti-abolitionist fantasies" in which black and white people were depicted as "fraternizing and socializing on equal terms."[80][81][82] Jerome B. Holgate's A Sojourn in the City of Amalgamation "painted a future in which sexual amalgamation was in fashion."[82]

Bob Jones University banned interracial dating until 2000.[83]

Asians were specifically included in the anti-miscegenation laws of some states. California continued to ban Asian/white marriages until the Perez v. Sharp decision in 1948.

In the United States, segregationists, including modern-day Christian Identity groups, have claimed that several passages in the Bible,[85] such as the stories of Phinehas (see Phineas Priesthood), the Curse and mark of Cain, and the curse of Ham, should be understood as referring to miscegenation and they also believe that certain verses in the Bible expressly forbid it.

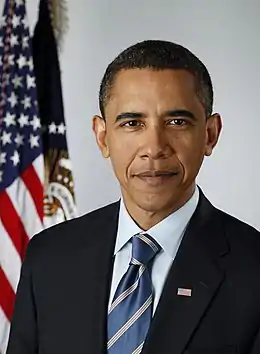

Interracial marriage has gained more acceptance in the United States since the civil rights movement.[86] Approval of mixed marriages in national opinion polls has risen from 4% in 1958, 20% in 1968 (at the time of the SCOTUS decision), 36% in 1978, to 48% in 1991, 65% in 2002, 77% in 2007, and 86% in 2011.[87][88] The most notable American of mixed race is the former President of the United States, Barack Obama, who is the product of a mixed marriage between a black father and a white mother. Nevertheless, as late as 2009, a Louisiana justice of the peace refused to issue a marriage license to an interracial couple, justifying the decision on grounds of concern for any future children which the couple might have.[89] The number of interracial marriages as a proportion of new marriages has increased from 11% in 2010 to 19% in 2019.[90]

Hawaii

The majority of Hawaiian Chinese were Cantonese-speaking migrants from Guangdong but a minority of them were Hakka. If all people with Chinese ancestry in Hawaii (including the Chinese-Hawaiians) are included, they form about 1/3 of Hawaii's entire population. A large percentage of Chinese immigrants married native-Hawaiian, European, and multi-racial Hawaiians. Intermarriage started to decline in the 1920s.[91][92] Portuguese Hawaiians and others of European ancestry often married Chinese immigrants and their descendants.[93][94] Birth records and census data from the 1930s demonstrate that children of mixed-parentage were often classified by only their father's ethnic identity, such as with 38 recorded births in between 1932 and 1933 to Portuguese-Chinese where the father was Chinese, reflecting American attitudes on racial purity.[91] A large amount of mingling took place between the Chinese community in Hawaii, with many Chinese-Hawaiians marrying people from the Portuguese, Spanish, Hawaiian, Caucasian-Hawaiian, and other communities.[95][96][97][98] Intermarrages in Hawaii were also documented between the Chinese and Puerto Rican, Portuguese, Japanese, Greek, and mixed-race individuals.[99][100]

Mexico

In Mexico, the concept of mestizaje (or the cultural and racial amalgamation) is an integral part of the country's identity. While frequently seen as a mixture of the indigenous and Spanish, Mexico has had a notable admixture of indigenous and black Africans since the Colonial era. The Catholic Church never opposed interracial marriages, although individuals had to declare their racial classification in the parish marital register.

Cuba

120,000 Cantonese coolies (all males) entered Cuba under contract for 80 years. Most did not marry, but Hung Hui (1975:80) states there was a frequency of sexual activity between black women and Cantonese coolies. According to Osberg, (1965:69) the Chinese often bought slave women and freed them, expressly for marriage. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Chinese men (Cantonese) engaged in sexual activity with white and black Cuban women, resulting in many children. (For a British Caribbean model of Chinese cultural retention through procreation with black women, see Patterson, 322–31).[101] In the 1920s an additional 30000 Cantonese and small groups of Japanese arrived. Both immigrations were exclusively male, and there was rapid mingling with white, black, and mulato populations.[102][103] In the CIA World Factbook: Cuba (15 May 2008) the authors estimated 114,240 people with Chinese-Cuban ancestry and only 300 pure Chinese.[104] In the study of genetic origin, admixture, and asymmetry in maternal and paternal human lineages in Cuba, 35 Y-chromosome SNPs were typed in the 132 male individuals of the Cuban sample. The study did not include any people with some Chinese ancestry. All the samples were white and black Cubans. 2 out of 132 male samples belong to East Asian Haplogroup O2 which is found in significant frequencies among Cantonese people.[105]

El Salvador

In El Salvador, there was frequent intermarriage between black male slaves and Amerindian women. Many of these slaves intermarried with Amerindian women in hopes of gaining freedom (if not for themselves, then their offspring). Many mixed African and Amerindian children resulted from these unions. The Spanish tried to prevent such Afro-Amerindian unions, but the mixing of the two groups could not be prevented. Slaves continued to pursue natives with the prospect of freedom. According to Richard Price's book Maroon Societies (1979), it is documented that during the colonial period that Amerindian women would rather marry black men than Amerindian men, and that black men would rather marry Amerindian women than black women so that their children will be born free. Price quoted this from a history by H.H. Bancroft published in 1877 referring to colonial Mexico. El Salvador's African population lived under similar circumstances, and the mixing between black men and native women was common during colonial times.[106]

Guatemala

There were many instances when black and mulatto men would intermarry with Mayan and other native women in Guatemala. These unions were more common in some regions than others. In Escuintla (called Escuintepeque at the time), the Pipil-speaking natives who lived at higher elevations tended to live away from the lowland coastal hot lands where black and mulatto men were concentrated. Yet, as black men grew in number during this period (1671–1701), a tendency developed for them to marry native women. In Zapotitlán (also known as Suchitepéquez), Spaniards were proportionately more significant than in Escuintla. Thus the smaller African population had less opportunity for endogamy and was disappearing by the early 18th Century as blacks married Mayans and mulattoes married mestizos and lower-ranking Spaniards. Finally in Guazacapán, a Pipil district that was 10% non-native, church marriages between Mayas or Pipils and free mulattoes were rare. But black men frequently married Mayan women in informal unions, which resulted in a significant population of mestizaje here and throughout the coastal region. In the Valle de las Vacas, black male slaves also intermarried with Mayan women.[107]

Costa Rica

The Chinese in Costa Rica originated from Cantonese male migrants. Pure Chinese make up only 1% of the Costa Rican population but, according to Jacqueline M. Newman, as much as ten percent of the people in Costa Rica are Chinese, if counting the people who are Chinese, married to a Chinese, or of mixed Chinese descent.[108] Most Chinese immigrants since then have been Cantonese, but in the last decades of the 20th century, a number of immigrants have also come from Taiwan. Many men came alone to work, married Costa Rican women, and speak Cantonese. However, the majority of the descendants of the first Chinese immigrants no longer speak Cantonese and think of themselves as full Costa Ricans.[109] They married Tican women (who are a blend of European, Castizo, Mestizo, Indian, Black).[110] A Tican is also a white person with a small amount of non-white blood, like Castizo. The 1989 census shows about 98% of Costa Ricans were either White, Castizo, Mestizos, with 80% being White or Castizo. Up to the 1940s men made up the vast majority of the Costa Rican Chinese community.[111] Males made up the majority of the original Chinese community in Mexico and they married Mexican women.[112]

Many Africans in Costa Rica also intermarried with other races. In late colonial Cartago, 33% of 182 married African males and 7% of married African females were married to a spouse of another race. The figures were even more striking in San Jose' where 55% of the 134 married African males and 35% of the 65 married African females were married to another race (mostly mestizos). In Cartago itself, two African males were enumerated with Spanish wives and three with Indian wives, while nine African females were married to Indian males. Spaniards rarely cohabited with mulatto women except in the cattle range region bordering Nicaragua to the north. There as well, two Spanish women were living with African males.[113]

Jamaica and Haiti

In Haiti, there is a sizable percentage within the minority who are of Asian descent. Haiti is also home to Marabou peoples, a half East Indian and half African people who descent from East Indian immigrants who arrived from other Caribbean nations, such Martinique and Guadeloupe and African slave descendants. Most present-day descendants of the original Marabou are products of hypodescent and, subsequently, mostly of African in ancestry.

The country also has a sizable Japanese and Chinese Haitian population. One of the country's most notable Afro-Asians is the late painter Edouard Wah who was born to a Chinese immigrant father and Afro-Haitian mother.

When black and Indian women had children with Chinese men the children were called chaina raial in Jamaican English.[114] The Chinese community in Jamaica was able to consolidate because an openness to marrying Indian women was present in the Chinese since Chinese women were in short supply.[115] Women sharing was less common among Indians in Jamaica according to Verene A. Shepherd.[116] The small number of Indian women were fought over between Indian men and led to a rise in the amount of wife murders by Indian men.[117] Indian women made up 11 percent of the annual amount of Indian indentured migrants from 1845 to 1847 in Jamaica.[118] Thousands of Chinese men and Indian men married local Jamaican women. The study "Y-chromosomal diversity in Haiti and Jamaica: Contrasting levels of sex-biased gene flow" shows the paternal Chinese haplogroup O-M175 at a frequency of 3.8% in local Jamaicans ( non-Chinese Jamaicans) including the Indian H-M69 (0.6%) and L-M20 (0.6%) in local Jamaicans.[119] Among the country's most notable Afro-Asians are reggae singers Sean Paul, Tami Chynn and Diana King.

South America

Latin America and the Caribbean

About 300,000 Cantonese coolies and migrants (almost all males) migrated during 1849–1874 to Latin America; many of them intermarried and cohabited with the Black, Mestizo, and European population of Cuba, Peru, Guyana, and Trinidad.

In addition, Latin American societies also witnessed growth in both Church-sanctioned and common law marriages between Africans and the non-colored.[113]

Argentina

In Buenos Aires in 1810, only 2.2 percent of African men and 2.5 percent of African women were married to the non-colored (white). In 1827, the figures increased to 3.0 percent for men and 6.0 percent for women. Racial mixing increased even further as more African men began enlisting in the army. Between 1810 and 1820 only 19.9% of African men were enlisted in the army. Between 1850 and 1860, this number increased to 51.1%. This led to a sexual imbalance between African men and women in Argentina. Unions between African women and non-colored men became more common in the wake of massive Italian immigration to the country. This led one African male editorial commentator to quip that, given to the sexual imbalance in the community, black women who "could not get bread would have to settle for pasta".[113]

Bolivia

During the colonial period, many black people often intermarried with the native population (mostly Aymara). The result of these relationships was the blending between the two cultures (Aymara and Afro-Bolivian).

After Bolivia's Agrarian Reform of 1953, black people (like indigenous people) migrated from their agricultural villages to the cities of La Paz, Cochabamba, and Santa Cruz in search of better educational and employment opportunities. Related to this, black individuals began intermarrying with people of lighter skin coloring such as blancos (whites) and mestizos. This was done as a means of better integration for themselves, and especially their children, into Bolivian society.[120]

Brazil

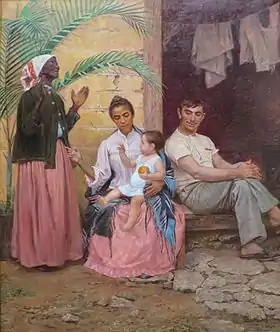

Brazil is the most populated country in Latin America as well as one of the most racially diverse. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, Brazil's racial composition is 48% white (92 million) 44% pardo (83 million) 7% black (13 million) 0.50% yellow (1.1 million).[121] The focus on skin color rather than racial origin is controversial. Due to its racial configuration, Brazil is often compared to the US in terms of its race relations, however, the presence of such a strong mixed population in Brazil is cited as being one of its main differences from the US.[122] The most recent censure in Brazil demonstrates that a considerable part of the population is non-white.[121] The pardo category denotes a mixed or multiracial composition. However, it could be further broken down into terms based on the main racial influences on an individual's phenotype.

Brazil's systematic collection of data on race is considered to be one of the most extensive in the region. However, the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) has been continuously criticized for its method of measuring racial demographics. An important distinction is that Brazil collects data based on color, not race. Thus the 'pardo' category does not actually pertain to a specific phenotype, only to the color of the individual. This means that a 'pardo' person can range from somebody with white and Amerindian ancestry to someone with African and Portuguese ancestry. There is an obvious difference between these two phenotypes that are not represented by the umbrella term of 'pardo'. There have been many studies focusing on the significance of the IBGE's focus on color rather than race. Ellis Monk has published research illustrating the implications of this racial framework on Brazilian society from a sociological perspective. In a discussion of how the government's implementation of a dichotomous white – non-white (mixed races, along with black and Amerindians) He states: "The Brazilian government, beginning in the 1990s, even led campaigns urging Brazilians to view themselves as racially dichotomous, as black or white on the basis of African ancestry, regardless of the color of their skin".[123] This development has continued as it had gained support from African Brazilians and Black consciousness movements who wished to set itself apart as a distinct race with black skin color, similar to the racial framework used in the U.S[123]

The early stages of the Portuguese colonies in Brazilian territory fostered a mixture between Portuguese colonizers, indigenous tribes, and African slaves. This composition was common in most colonies in Latin America. In this sense, several sociologists have compared the Brazilian colonial experience to that of Mexico. Since the publishing of Gilberto Freyre's seminal work Casa-Grande & Senzala, sociologists have looked at Brazil as having a unique colonial history where interracial relations were accepted without religious or class prejudices. Freyre says:

The sentiment of nationality in the Brazilian has been deeply affected by the fact that the feudal system did not here permit of a State that was wholly dominant or a Church that was omnipotent, as well as by the circumstance of miscegenation as practiced under the wing of that system and at the same time practiced against it, thus rendering less easy the absolute identification of the ruling class with the pure or quasi-pure European stock of the principal conquerors, the Portuguese. The result is a national sentiment tempered by a sympathy for the foreigner that is so broad as to become, practically, universalism. It would, indeed, be impossible to conceive of a people marching onward toward social democracy that in place of being universal in its tendencies should be narrowly exclusive or ethnocentric.

For Freyre, lack of sexual prejudices incentivized racial mixing that produces the wide genetic variety we see today. Portuguese men married and had children with indigenous and African women. The societal consequences of this are that a marked diversification of skin colors occur, blurring the racial ancestry of those considered to have 'mixed race. The increase of influence of one race over another in producing a Brazilian phenotype happened in stages. For example, immigration policy loosened in the late 1940s resulting in the influx of multiple European communities that are now considered to have 'whitened' Brazilian communities in the north and northeast.[124]

British West Indies

Miscegenation has never been illegal in the British West Indies, and the populations of Guyana,[125][126][127] Belize,[128][129][130] Jamaica,[131][132] and Trinidad[133][134][135][136] are today among the world's most diverse.

Peru

About 100,000 Chinese coolies (almost all males) from 1849 to 1874 migrated to Peru and intermarried with Peruvian women of Mestizo, European, Amerindian, European/Mestizo, African and mulatto origin. Thus, many Peruvian Chinese today are of mixed Chinese, Spanish, African, or Amerindian ancestry. One estimate for the Chinese-Peruvian mixture is about 1.3–1.6 million. Asian Peruvians are estimated to be 3% of the population, but one source places the number of citizens with some Chinese ancestry at 4.2 million, which equates to 15% of the country's total population.[137] In Peru, non-Chinese women married the mostly male Chinese coolies.[138]

Among the Chinese migrants who went to Peru and Cuba there were almost no women.[139][140] Some Peruvian women married Chinese male migrants.[141][142][143][144][145] Chinese men formed relationship with both Peruvian women and Afro-Peruvian women during their labor as coolies. Chinese men had contact with Peruvian women in cities, there they formed relationships had mixed-race babies. These women came from Andean and coastal areas and did not originally come from the cities, in the haciendas on the coast in rural areas, native young women of indígenas (native) and serranas (mountain) origin from the Andes mountains would come to work, these Andean native women were favored as marital partners by Chinese men over Africans. Matchmakers arranged marriages of Chinese men to indígenas and serranas young women.[146] There was a racist reaction by some Peruvians to the marriages of Peruvian women and Chinese men.[147] When native Peruvian women (cholas and natives, Indias, indígenas) and Chinese men had mixed children, the children were called injertos. When these injertos became a components of Peruvian society, Chinese men then sought out girls of injertos origins as marriage partners. Children born to black mothers were not called injertos.[148] Lower class Peruvians established sexual unions or marriages with the Chinese men and some black and Indian women "bred" with the Chinese according to Alfredo Sachettí, who claimed the mixing was causing the Chinese to suffer from "progressive degeneration", in Casa Grande highland Indian women and Chinese men participated in communal "mass marriages" with each other, arranged when highland women were brought by a Chinese matchmaker after receiving a down payment.[145][149]

In Peru and Cuba some Indian (Native American), mulatto, black, and white women married or had sexual relations with Chinese men, with marriages of mulatto, black, and white woman being reported by the Cuba Commission Report and in Peru it was reported by the New York Times that Peruvian black and Indian (Native) women married Chinese men to their own advantage and to the disadvantage of the men since they dominated and "subjugated" the Chinese men despite the fact that the labor contract was annulled by the marriage, reversing the roles in marriage with the Peruvian woman holding marital power, ruling the family and making the Chinese men slavish, docile, "servile", "submissive" and "feminine" and commanding them around, reporting that "Now and then ... he [the Chinese man] becomes enamored of the charms of some sombre-hued chola (Native Indian and mestiza woman) or samba (a mixed black woman), and is converted and joins the Church, so that may enter the bonds of wedlock with the dusky señorita."[150] Chinese men were sought out as husbands and considered a "catch" by the "dusky damsels" (Peruvian women) because they were viewed as a "model husband, hard-working, affectionate, faithful and obedient" and "handy to have in the house", the Peruvian women became the "better half" instead of the "weaker vessel" and would command their Chinese husbands "around in fine style" instead of treating them equally, while the labor contract of the Chinese coolie would be nullified by the marriage, the Peruvian wife viewed the nullification merely as the previous "master" handing over authority over the Chinese man to her as she became his "mistress", keeping him in "servitude" to her, speedily ending any complaints and suppositions by the Chinese men that they would have any power in the marriage.[151]

Asia

Inter-ethnic marriage in Southeast Asia dates back to the spread of Indian culture, Hinduism and Buddhism to the region. From the 1st century onwards, mostly male traders and merchants from the Indian subcontinent frequently intermarried with the local female populations in Cambodia, Burma, Champa, Central Siam, the Malay Peninsula, and Malay Archipelago. Many Indianized kingdoms arose in Southeast Asia during the Middle Ages.[152]

From the 9th century onwards, a large number of mostly male Arab traders from the Middle East settled down in the Malay Peninsula and Malay Archipelago, and they intermarried with the local Malay, Indonesian and female populations in the islands later called the Philippines. This contributed to the spread of Islam in Southeast Asia.[153] From the 14th to the 17th centuries, many Chinese, Indian and Arab traders settled down within the maritime kingdoms of Southeast Asia and intermarried with the local female populations. This tradition continued among Portuguese traders who also intermarried with the local populations.[154] In the 16th and 17th centuries, thousands of Japanese people also travelled to Southeast Asia and intermarried with the local women there.[155]

From the tenth to twelfth century, Persian women were to be found in Guangzhou (Canton), some of them in the tenth century like Mei Zhu in the harem of the Emperor Liu Chang, and in the twelfth century large numbers of Persian women lived there, noted for wearing multiple earrings and "quarrelsome dispositions".[156] Multiple women originating from the Persian Gulf lived in Guangzhou's foreign quarter, they were all called "Persian women" (波斯婦 Po-ssu-fu or Bosifu).[157] Some scholars did not differentiate between Persian and Arab, and some say that the Chinese called all women coming from the Persian Gulf "Persian Women".[158]

The exact number of Amerasians in Vietnam are not known. The U.S soldiers stationed in Vietnam had relationships with locals females, many of the women had origins from clubs, brothels and pubs. The American Embassy once reported there were less than a 1,000 Amerasians. A report by the South Vietnamese Senate Subcommittee suggested there are 15,000 to 20,000 children of mixed American and Vietnamese blood, but this figure was considered low.[159] Congress estimated 20,000 to 30,000 Amerasians by 1975 lived in Vietnam.[160] According to Amerasians Without Borders, they estimated about 25,000 to 30,000 Vietnamese Amerasians were born from American first participation in Vietnam in 1962, and lasted until 1975.[161] Although during the Operation Babylift it was estimated at 23,000.[162]

During World War II, Japanese soldiers engaged in war rape during their invasions across East Asia and Southeast Asia. Some Indo Dutch women, captured in Dutch colonies in Asia, were forced into sexual slavery.[163] More than 20,000 Indonesian women[164] and nearly 300 Dutch women were so treated.[165] A estimated 1000 Timor women and girls who also used as sexual slaves.[166] Melanesian women from New Guinea were also used as comfort women by the Japanese military and as well married Japanese, forming a small number of mixed Japanese-Papuan women born to Japanese fathers and Papuan mothers.[167]

The Indonesian invasion of East Timor and West Papua caused the murders of approximately 300,000 to 400,000 West Papuans and many thousands of women raped.[168]

Sex tourism has emerged in the late 20th century as a controversial aspect of Western tourism and globalization. Sex tourism is typically undertaken internationally by tourists from wealthier countries. Author Nils Ringdal alleges that three out of four men between the ages of 20 and 50 who have visited Asia or Africa have paid for sex.[169]

Female sex tourism also emerged in the late 20th century in Bali. Tens of thousands of single women throng the beaches of Bali in Indonesia every year. For decades, young Balinese men have taken advantage of the louche and laid-back atmosphere to find love and lucre from female tourists—Japanese, European and Australian for the most part—who by all accounts seem perfectly happy with the arrangement.[170]

Central Asia

Central Asians have descended from a mixture of various peoples, such as the Mongols, Turks, and Iranians. The Mongol conquest of Central Asia in the 13th century resulted in the mass killings of the Iranian-speaking people and Indo-Europeans population of the region, their culture and languages being superseded by that of the Mongolian-Turkic peoples. The remaining surviving population intermarried with invaders.[171][172][173][174] Genetic shows a mixture of East Asian and Caucasian ancestry in all Central Asian people.[175][176]

Afghanistan

Genetic analysis of the Hazara people indicate partial Mongolian ancestry.[177] Invading Mongols and Turco-Mongols mixed with the local Iranian population, forming a distinct group. Mongols settled in what is now Afghanistan and mixed with native populations who spoke Persian. A second wave of mostly Chagatai Mongols came from Central Asia and were followed by other Mongolic groups, associated with the Ilkhanate and the Timurids, all of whom settled in Hazarajat and mixed with the local, mostly Persian-speaking population, forming a distinct group.

The analysis also detected Sub-Saharan African lineages in both the paternal and maternal ancestry of Hazara. Among the Hazaras there are 7.5% of African mtDNA haplogroup L with 5.1% of African Y-DNA B.[178][179] The origin and date of when these admixture occurred are unknown but was believed to have been during the slave trades in Afghanistan.[179]

China

Intermarriage was initially discouraged by the Tang dynasty. In 836 Lu Chun was appointed as governor of Canton, he was disgusted to find Chinese living with foreigners and intermarriage between Chinese and foreigners. Lu enforced separation, banning interracial marriages, and made it illegal for foreigners to own property. Lu Chun believed his principles were just and upright.[180] The 836 law specifically banned Chinese from forming relationships with "dark peoples", which was used to describe foreigners, such as "Iranians, Sogdians, Arabs, Indians, Malays, Sumatrans", among others.[181][182] The Song dynasty allowed third-generation immigrants with official titles to intermarry with Chinese imperial princesses.[183]

Iranian, Arab, and Turkic women also occasionally migrated to China and mixed with Chinese.[183] From the tenth to twelfth century, Persian women were to be found in Guangzhou (Canton), some of them in the tenth century like Mei Zhu in the harem of the Emperor Liu Chang, and in the twelfth century large numbers of Persian women lived there, noted for wearing multiple earrings and "quarrelsome dispositions".[156][184] Multiple women originating from the Persian Gulf lived in Guangzhou's foreign quarter; they were all called "Persian women" (波斯婦; Po-szu-fu or Bosifu).[185] Iranian female dancers were in demand in China during this period. During the Sui dynasty, ten young dancing girls were sent from Persia to China. During the Tang dynasty bars were often attended by Iranian or Sogdian waitresses who performed dances for clients.[180][186][187][188]

During the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period (Wudai) (907–960), there are examples of Persian women marrying Chinese emperors. Some Chinese officials from the Song Dynasty era also married women from Dashi (Arabia).[189]

By the 14th century, the total population of Muslims in China had grown to 4 million.[190] After Mongol rule had been ended by the Ming dynasty in 1368, this led to a violent Chinese backlash against West and Central Asians. In order to contain the violence, both Mongol and Central Asian Semu Muslim women and men of both sexes were required by Ming Code to marry Han Chinese after the first Ming Emperor Hongwu passed the law in Article 122.[191][192][193]

Han women who married Hui men became Hui, and Han men who married Hui women also became Hui.[194][195][196]

Of the Han Chinese Li family in Quanzhou, Li Nu, the son of Li Lu, visited Hormuz in Persia in 1376, married a Persian or an Arab girl, and brought her back to Quanzhou. He then converted to Islam. Li Nu was the ancestor of the Ming Dynasty reformer Li Chih.[197][198][199]

After the Oghuz Turkmen Salars moved from Samarkand in Central Asia to Xunhua, Qinghai in the early Ming dynasty, they converted Tibetan women to Islam and the Tibetan women were taken as wives by Salar men. A Salar wedding ritual where grains and milk were scattered on a horse by the bride was influenced by Tibetans.[200] After they moved into northern Tibet, the Salars originally practiced the same Gedimu (Gedem) variant of Sunni Islam as the Hui people and adopted Hui practices like using the Hui Jingtang Jiaoyu Islamic education during the Ming dynasty which derived from Yuan dynasty Arabic and Persian primers. One of the Salar primers was called "Book of Diverse Studies" (杂学本本; Zá xué běnběn) in Chinese. The version of Sunni Islam practiced by Salars was greatly impacted by Salars marrying with Hui who had settled in Xunhua. The Hui introduced new Naqshbandi Sufi orders like Jahriyya and Khafiyya to the Salars and eventually these Sufi orders led to sectarian violence involving Qing soldiers (Han, Tibetans and Mongols) and the Sufis which included the Chinese Muslims (Salars and Hui). Ma Laichi brought the Khafiyya Naqshbandi order to the Salars and the Salars followed the Flowered mosque order (花寺門宦) of the Khafiyya. He preached silent dhikr and simplified Qur'an readings bringing the Arabic text Mingsha jing (明沙經, 明沙勒, 明沙爾 Minshar jing) to China.[201]

The Kargan Tibetans, who live next to the Salar, have mostly become Muslim due to the Salars. The Salar oral tradition recalls that it was around 1370 in which they came from Samarkand to China.[202][203] The later Qing dynasty and Republic of China Salar General Han Youwen was born to a Tibetan woman named Ziliha (孜力哈) and a Salar father named Aema (阿额玛).[204][205][206]

Tibetan women were the original wives of the first Salars to arrive in the region as recorded in Salar oral history. The Tibetans agreed to let their Tibetan women marry Salar men after putting up several demands to accommodate cultural and religious differences. Hui and Salar intermarry due to cultural similarities and following the same Islamic religion. Older Salars married Tibetan women but younger Salars prefer marrying other Salars. Han and Salar mostly do not intermarry with each other unlike marriages of Tibetan women to Salar men. Salars however use Han surnames. Salar patrilineal clans are much more limited than Han patrilineal clans in how much they deal with culture, society or religion.[207][208] Salar men often marry a lot of non-Salar women and they took Tibetan women as wives after migrating to Xunhua according to historical accounts and folk histories. Salars almost exclusively took non-Salar women as wives like Tibetan women while never giving Salar women to non-Salar men in marriage except for Hui men who were allowed to marry Salar women. As a result, Salars are heavily mixed with other ethnicities.[209]

Salars in Qinghai live on both banks of the Yellow river, south and north, the northern ones are called Hualong or Bayan Salars while the southern ones are called Xunhua Salars. The region north of the Yellow river is a mix of discontinuous Salar and Tibetan villages while the region south of the yellow river is solidly Salar with no gaps in between, since Hui and Salars pushed the Tibetans on the south region out earlier. Tibetan women who converted to Islam were taken as wives on both banks of the river by Salar men. The term for maternal uncle (ajiu) is used for Tibetans by Salars since the Salars have maternal Tibetan ancestry. Tibetans witness Salar life passages in Kewa, a Salar village and Tibetan butter tea is consumed by Salars there as well. Other Tibetan cultural influences like Salar houses having four corners with a white stone on them became part of Salar culture as long as they were not prohibited by Islam. Hui people started assimilating and intermarrying with Salars in Xunhua after migrating there from Hezhou in Gansu due to the Chinese Ming dynasty ruling the Xunhua Salars after 1370 and Hezhou officials governed Xunhua. Many Salars with the Ma surname appear to be of Hui descent since a lot of Salars now have the Ma surname while in the beginning the majority of Salars had the Han surname. Some example of Hezhou Hui who became Salars are the Chenjia (Chen family) and Majia (Ma family) villages in Altiuli where the Chen and Ma families are Salars who admit their Hui ancestry. Marriage ceremonies, funerals, birth rites and prayer were shared by both Salar and Hui as they intermarried and shared the same religion since more and more Hui moved into the Salar areas on both banks of the Yellow river. Many Hui married Salars and eventually it became far more popular for Hui and Salar to intermarry due to both being Muslims than to non-Muslim Han, Mongols and Tibetans. The Salar language and culture however was highly impacted in the 14th-16th centuries in their original ethnogenesis by marriage with Mongol and Tibetan non-Muslims with many loanwords and grammatical influence by Mongol and Tibetan in their language. Salars were multilingual in Salar and Mongol and then in Chinese and Tibetan as they trade extensively in the Ming, Qing and Republic of China periods on the yellow river in Ningxia and Lanzhou in Gansu.[210]

Salars and Tibetans both use the term maternal uncle (ajiu in Salar and Chinese, azhang in Tibetan) to refer to each other, referring to the fact that Salars are descendants of Tibetan women marrying Salar men. After using these terms they often repeat the historical account how Tibetan women were married by 2,000 Salar men who were the First Salars to migrate to Qinghai. These terms illustrate that Salars were viewed separately from the Hui by Tibetans. According to legend, the marriages between Tibetan women and Salar men came after a compromise between demands by a Tibetan chief and the Salar migrants. The Salar say Wimdo valley was ruled by a Tibetan and he demanded the Salars follow four rules in order to marry Tibetan women. He asked them to install on their houses's four corners Tibetan Buddhist prayer flags, to pray with Tibetan Buddhist prayer wheels with the Buddhist mantra om mani padma hum and to bow before statues of Buddha. The Salars refused those demands saying they did not recite mantras or bow to statues since they believed in only one creator god and were Muslims. They compromised on the flags in houses by putting stones on their houses' corners instead of Tibetan Buddhist prayer flags. Some Tibetans do not differentiate between Salar and Hui due to their Islamic religion. In 1996, Wimdo township only had one Salar because Tibetans whined about the Muslim call to prayer and a mosque built in the area in the early 1990s so they kicked out most of the Salars from the region. Salars were bilingual in Salar and Tibetan due to intermarriage with Tibetan women and trading. It is far less likely for a Tibetan to speak Salar.[211] Tibetan women in Xiahe also married Muslim men who came there as traders before the 1930s.[212]

In eastern Qinghai and Gansu there were cases of Tibetan women who stayed in their Buddhist Lamaist religion while marrying Chinese Muslim men and they would have different sons who would be Buddhist and Muslims, the Buddhist sons became Lamas while the other sons were Muslims. Hui and Tibetans married Salars.[213]

In the frontier districts of Sichuan, numerous half Chinese-Tibetans were found. Tibetan women were glad to marry Chinese traders and soldiers.[214] Some Chinese traders married Tibetan girls.[215] Traders and officials in ancient times were often forbidden to bring Chinese women with them to Tibet, so they tended to marry Tibetan women; the male offspring were considered Chinese and female offspring as Tibetan.[216][217][218] Special names were used for these children of Chinese fathers and Tibetan mothers.[219] They often assimilated into the Tibetan population.[220] Chinese and Nepalese in Tibet married Tibetan women.[221]

Chinese men also married Turkic Uyghur women in Xinjiang from 1880 to 1949. Sometimes poverty influenced Uyghur women to marry Chinese. These marriages were not recognized by local mullahs since Muslim women were not allowed to marry non-Muslim men under Islamic law. This did not stop the women because they enjoyed advantages, such as not being subject to certain taxes. Uyghur women married to the Chinese also did not have to wear a veil and they received their husband's property upon his death. These women were forbidden from being buried in Muslim graves. The children of Chinese men and Uyghur women were considered as Uyghur. Some Chinese soldiers had Uyghur women as temporary wives, and after the man's military service was up, the wife was left behind or sold, and if it was possible, sons were taken, and daughters were sold.[222]

After the Russian Civil War, a huge number of Russians settled in the Manchuria region of China. One Chinese scholar Zhang Jingsheng wrote essays in 1924 and 1925 in various Chinese journals praising the advantages of miscegenation between Russians and Chinese, saying that interracial sex would promote greater understandings between the two peoples, and produce children with the best advantages of both peoples.[223] Zhang argued that Russians were taller and had greater physical strength than the Han, but the Chinese were gentler and kinder than the Russians, and so intermarriage between the two peoples would ensure children with the advantages of both.[223] Zhang wrote that the Russians were a tough "hard" people while the Chinese had a softer physique and more compassion, and miscegenation between the two would only benefit both.[223] Zhang mentioned since 1918 about one million Russian women who had already married Chinese men and argued already the children born of these marriages had the strength and toughness of the Russians and the gentleness and kindness of the Chinese.[223] Zhang wrote what he ultimately wanted was an "Asia for Asians", and believed his plans for miscegenation were the best way of achieving this.[223] The South Korean historian Bong Inyoung wrote that Zhang's plans were based on a certain Social Darwinist thinking and a tendency to assign characteristics to various peoples in a way that might be considered objectionable today, but he was no racist as he did not see fair skin of the Russians as any reason why the Chinese should not marry them.[223]

European travellers noted that many Han Chinese in Xinjiang married Uyghur (who were called turki) women and had children with them. A Chinese was spotted with a "young" and "good looking" Uyghur wife and another Chinese left behind his Uyghur wife and child in Khotan.[224][225][226][227]

After 1950, some intermarriage between Han and Uyghur peoples continued. A Han married a Uyghur woman in 1966 and had three daughters with her, and other cases of intermarriage also continued.[228][229]

Ever since the 1960s, African students were allowed by the Chinese government to study in China as friendly relations with Africans and African-related people was important to CCP's "Third World" coalition. Many African male students began to intermingle with the local Chinese women. Relationships between black men and Chinese women often led to numerous clashes between Chinese and African students in the 1980s as well as grounds for arrest and deportation of African students. The Nanjing anti-African protests of 1988 were triggered by confrontations between Chinese and Africans. New rules and regulations were made in order to stop African men from consorting with Chinese women. Two African men who were escorting Chinese women on a Christmas Eve party were stopped at the gate and along with several other factors escalated. The Nanjing protests lasted from Christmas Eve of 1988 to January 1989. Many new rules were set after the protests ended, including one where black men could only have one Chinese girlfriend at a time whose visits were limited to the lounge area.[230]

There is a small but growing population of mixed marriages between male African (mostly Nigerian) traders and local Chinese women in the city of Guangzhou where it is estimated that in 2013 there are 400 African-Chinese families.[231] The rise in mixed marriages has not been without controversy. The state, fearing fraud marriages, has strictly regulated matters. In order to obtain government-issued identification (which is required to attend school), the children must be registered under the Chinese mother's family name. Many African fathers, fearing that in doing so, they would relinquish their parental rights, have instead chosen to not send their children to school. There are efforts to open an African-Chinese school but it would first require government authorization.[231]

Taiwan

During the Siege of Fort Zeelandia of 1661–1662 in which Chinese Ming loyalist forces commanded by Koxinga besieged and defeated the Dutch East India Company and conquered Taiwan, the Chinese took Dutch women and children prisoner. Koxinga took Hambroek's teenage daughter as a concubine,[232][233][234] and Dutch women were sold to Chinese soldiers to become their wives. In 1684 some of these Dutch wives were still captives of the Chinese.[235]

Some Dutch physical looks like auburn and red hair among people in regions of south Taiwan are a consequence of this episode of Dutch women becoming concubines to the Chinese commanders.[236]

Hong Kong