Various examples of violence have been attributed to racial factors during the recorded history of Australia since white settlement, and a level of intertribal rivalry and violence among Indigenous Australians pre-dates the arrival of white settlers from the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1788.

During the period of British colonisation, various incidents of inter-racial tension and competition for land and resources between Europeans and Indigenous peoples involved violence, becoming a factor in the decline of indigenous populations during the 19th century. Incidents of racial violence between settler communities followed the large scale multi-ethnic immigration of the Australian goldrushes of the mid-19th century – notably white miners targeting Chinese miners – which contributed to the development of the White Australia Policy which preferenced British and "white" immigration to Australia for some decades. The policy resulted in a largely white race population by the mid-20th century.

Australia's large scale, post-war, multi-ethnic immigration program has seen Australia develop into one of the most ethnically diverse nations, with relatively little racial violence, and in which incitement to racial violence is a crime. Nevertheless, incidents and examples of violence between the various ethnicities of modern Australia have continued to be attributed to racial motivations up to the present time.

History

Racial violence in Australia is evident through various past and more recent events. Hate crimes and racial violence are not new concepts[1]

Australia's recorded history begins with the arrival of the British First Fleet at Sydney in 1788. During the course of the 19th century, the British Empire progressively asserted control over the Australian continent. Skirmishes and battles between early European settlers and indigenous Australians which occurred during this period may not all be classified as "racially motivated" violence however, given that they were very often punitive or defensive attacks by one side or other engaged in a drawn out competition for land, resources and sites of cultural significance. Nevertheless, there were clear incidents of racially motivated violence occurring during the colonial period in Australia.

Attacks against the indigenous population by settlers resulted in the deaths of thousands of Aboriginals, and in particular devastated the indigenous population of Tasmania. [2] Violence against the Chinese community also occurred early in Australia's history, with mobs attacking rival Chinese miners.[3]

The White Australia policy was developed in the late 19th century and formalised soon after Federation in 1901, and was aimed at maintaining a racially homogenous Australia. It was dismantled progressively from the mid twentieth century. Post 1950's multicultural has seen occasional violence with a racial element – among and between both old and new immigrant groups. Ethnic gang violence has also occurred. Some have attributed racial violence to attitudes expressed by media and politicians.[4]

Commentators have discussed the concept of the risk society, particularly as it relates to the Cronulla riots. There is a sense that in Australia and in other Western countries, racism has been based upon notions of xenophobia.[5] Recently, technology has aided the organising of racial violence via SMS texting.[6]

European settlement and Indigenous Australians

The early European exploration and colonisation of Australia often led to violent and deadly conflicts between the original inhabitants, the Aboriginal populations, and Europeans throughout the continent, from the arrival of early European mariners and arrival of the British First Fleet at Sydney in 1788, to the time of the Caledon Bay Crisis of the 1930s. Racism often played a role in this violence, though competition for land and resources and cultural misunderstandings over differing views of such concepts as sacred spaces and property ownership were also common motivators.

By 1788, Indigenous Australians had not developed a system of writing, so the first literary accounts of Aborigines come from the journals of early European explorers, which contain descriptions of first contact, both violent and friendly: a 1644 account of Willem Jansz's 1606 landing at Cape York (the first known landing by a European in Australia) refers to "savage, cruel black barbarians who slew some of our sailors", while the English buccaneer William Dampier wrote of the "natives of New Holland" as "barbarous savages", but by the time of Captain James Cook and First Fleet marine Watkin Tench (the era of Jean-Jacques Rousseau), accounts of Aborigines were more sympathetic and romantic: "these people may truly be said to be in the pure state of nature, and may appear to some to be the most wretched upon the earth; but in reality they are far happier than ... we Europeans", wrote Cook in his journal on 23 August 1770.[7]

The first Governor of New South Wales, Arthur Phillip, was instructed explicitly to establish friendship and good relations with the Aborigines and interactions between the early newcomers and the ancient landowners varied considerably throughout the colonial period—from the mutual curiosity displayed by the early interlocutors of Sydney, to the outright hostility of Pemulwuy and Windradyne of the Sydney region,[8] and Yagan around Perth. Pemulwuy was accused of the first killing of a white settler in 1790, and Windradyne resisted early British expansion beyond the Blue Mountains.[9] According to the historian Geoffrey Blainey, in Australia during the colonial period: "In a thousand isolated places there were occasional shootings and spearings. Even worse, smallpox, measles, influenza and other new diseases swept from one Aboriginal camp to another ... The main conqueror of Aborigines was to be disease and its ally, demoralisation".[10]

Relatively small numbers of White settlers and convicts removed Aboriginal populations from much of South Eastern Australia.[11] The island of Tasmania's small, though culturally unique, Aboriginal population in particular suffered – the majority of them succumbing to introduced disease, being killed in conflict with white settlers, or dying early as a result of displacement or competition for resources in the decades following European settlement.

Lambing Flat riots

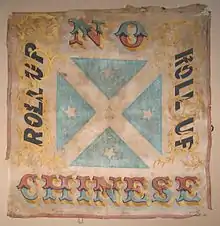

The Australian gold rushes of the 19th century brought great wealth but also new social tensions. Multiethnic migrants came to New South Wales in large numbers for the first time. Young became the site of an infamous Lambing Flat anti-Chinese miner riot in 1861 and the official Riot Act was read to the miners on 14 July – the only official reading in the history of New South Wales.[12] Riots occurred on the goldfields at Spring Creek, Stoney Creek, Back Creek, Wombat, Blackguard Gully, Tipperary Gully, and Lambing Flat (now Young, New South Wales), in 1860–1861.

There was ten months of unrest at Burrangong involving disputes against Chinese miners, where they were often driven off their 'digs'. The most infamous riot occurred on the night of 30 June 1861 when a group of perhaps 3,000 drove the Chinese off Lambing Flat, and then moved on to the Back Creek diggings, destroying tents and looting possessions. About 1,000 Chinese abandoned the field. Many of the victims were brutally beaten, but there were no deaths. The only death related to this incident was of a white miner killed by police trying to break up the disturbance. .[3]

Kalgoorlie Mines race riots

These race riots were between white Australian miners and Southern Europeans living in the area. There had been simmering tensions on Kalgoorlie between Italian migrants and local white Australians. This had resulted in a race riot in 1919. The civil disturbance in 1934 was larger. It initially started during the Australia Day weekend of 1934. An inebriated British miner, Edward Jordan, instigated a fight with an Italian barman, Claudio Mattaboni. Edward Jordan was a popular local, who was also a footballer, firefighter and tribute miner. After instigating the fight himself, Jordan cracked his skull on the pavement and died several hours later.

The following day, aided by Jordan's drinking friends, rumours spread that the popular local had been murdered by Mattaboni. Mourners attended Jordans funeral in their hundreds, then after drinking at several wakes, gathered in Hannan Street near several migrant-owned businesses. A youth instigated the riot by throwing a stone through a window of the Kalgoorlie Wine Saloon and full-scale rioting ensued. Rioters burned the building to the ground, then moved on to attack other migrant-run establishments. A large group of rioters stole a tram and rode to the nearby town of Boulder, where the destruction continued.[13]

The rioting had stopped by the next day, but the disgruntled locals tried to organise to eject Southern European migrant workers from the mines. After meetings about this were attended by some hundreds of people, rioting once again ensued. Two people were killed, and 86 were arrested.[14]

Broome race riots

In 1920, Japanese residents of Broome in Western Australia attacked Timorese living there. The racial violence continued for a week, and was the most violent in the last century. 60 people were injured and 7 killed.[15]

Ethnic Groups Organized Crime (Sydney gang rapes)

The Sydney gang rapes were a series of gang rape attacks committed by a group of up to fourteen Lebanese Australian men led by Bilal Skaf against white Australian teenage girls, as young as 14, in Sydney Australia in 2000. The crimes were described as ethnically motivated hate crimes by officials and commentators. [16] [17]

Cronulla riots

The Cronulla riots of 2005[18] were a series of mob confrontations, with racial overtones, which originated in and around Cronulla, a beachfront suburb of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Soon after the riot, ethnically motivated violence occurred in several other Sydney suburbs.

On Sunday, 4 December 2005, police were called to North Cronulla Beach following a report of an assault on two off-duty surf lifesavers by members of a group of men of Middle Eastern appearance.[19][20][21][22][23] Lifesavers have occupied a position of high esteem within Australia and Sydney media outlets expressed outrage that volunteer lifesavers could be assaulted. Some called for protest.

On Sunday, 11 December 2005, approximately 5000 people gathered to protest against alleged incidents of assaults and intimidatory behaviour by groups of Middle Eastern looking youths from the suburbs of South Western Sydney. The crowd initially assembled without incident, but after excessive alcohol consumption, violence broke out after a segment of the mostly white[24] crowd chased a man of Middle Eastern appearance into a hotel and two other youths of Middle Eastern appearance were assaulted on a train. Police and ambulance officers were also attacked. The racist aspect of the incidents was reported widely overseas.

The next day a number of revenge attacks occurred. Large numbers of Middle Eastern men gathered in Punchbowl in Sydney's West, police being ordered not to confront them. Revenge attacks by Middle Eastern men against white Australias occurred in various suburbs, including a stabbing of a man at Woolooware, [25] a man being attacked by an iron bar while in his car,[26] gunshots being fired at parked cars at Christian church services and a church hall in Auburn in the city's west was burned down.[27]

SBS / Al Jazeera (for Al Jazeera) explores these events in their 2013 (2015) four-part documentary series "Once Upon a Time in Punchbowl", specifically in last two episodes, "Episode three, 2000–2005" and "Episode four, 2005–present".[28]

Attacks against Indian students

Australia is a popular destination for students from India. During 2009, some media in Australia and India publicised reports of crimes and robberies against Indians in Australia and alleged that they were racially motivated crimes. There were 120,913 Indian students enrolled to undertake an Australian qualification in 2009 and India was the second top-source country for Australia's international education industry.[29] A subsequent Indian Government investigation concluded that out of 152 reported assaults against Indian students in Australia that year, 23 such incidents involved "racial overtones".[30] in 2011, the Australian Institute of Criminology released a study entitled Crimes Against International Students:2005–2009.[31] This found that over the period 2005–2009, international students were statistically less likely to be assaulted than the average person in Australia. Indian students experienced an average assault rate in some jurisdictions, but overall they experienced lower assault rates than the Australian average. They did, however, experience higher rates of robbery, overall.[32] Additionally, multiple surveys of international students over the period of 2009–10 found a majority of Indian students felt safe.[33]

Nevertheless, a number of people alleged that Melbourne had a problem of racist attacks. In Melbourne, on 30 May 2009, Indian students protested against "racist" attacks. Thousands of students gathered outside the Royal Melbourne Hospital where one of the victims of an assault had been admitted. The protest, however, was called off early on the next day morning after the protesters accused police of "ramrodding" them to break up their sit-in.[34]

In Sydney, around 150 – 200 Indian men gathered to protest against police inaction about attacks on them by Lebanese Australian Youths in Harris Park, in the city's west. Groups of Lebanese youths from the area also attended the scene resulting in some clashes, though police presence stopped further affray. The protest went on for three days. [35] [36] Australian High Commissioner to India John McCarthy said that there was an element of racism involved in the attacks on Indians.[37]

Racial violence and media reporting

There are often discrepancies in how the media reports 'racial' violence and 'race' riots. The Australian media has been accused of using stereotypes of indigenous peoples to that groups' detriment.[38] Some mainstream media outlets publish racialised opinion pieces that unfairly portray groups in a negative light.[39]

Sydney talkback radio commentator Alan Jones was found by a New South Wales State Government Tribunal to have "incited hatred, serious contempt and severe ridicule of Lebanese Muslims", describing them as "vermin" who "rape and pillage a nation that's taken them in", in the lead-up to the 2005 Cronulla race riots.[40]

Individual race-based crimes in court

Individual race-based crimes have attracted a variety of penalties in Australian legal jurisdictions. The Sydney Morning Herald reported in early 2010 that an Anglo-Australia man, was ordered to pay over A$130,000 to an Asian-Australian man that he bashed outside the victim's house. The drunken attacker shouted racial slurs at the victim. The accused assaulted the victim with a piece of wood – the victim sustained a fractured leg and a partial facial nerve palsy.[41]

See also

References

- ↑ Donald P. Green, Laurence H. McFalls, Jennifer K. Smith Hate Crime: An Emergent Research Agenda Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 27: 479–504

- ↑ (2) The Fatal Confrontation: Early Native-White Relations on the Frontiers of Australia, New Guinea, and America: A Comparative Study Author(s): Wilbur R. Jacobs Source: The Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 40, No. 3 (Aug. 1971), pp. 283–309 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3638359 (1) 299

- 1 2 "1860 Lambing Flat Roll Up Banner". Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ↑ Simmons, K Modern racism in the media: constructions of 'the possibility of change' in accounts of two Australian 'riots' DISCOURSE & SOCIETY 19 (5): 667–687 SEP 2008

- ↑ Judy Lattas Cruising: 'Moral Panic' and the Cronulla Riot THE AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF ANTHROPOLOGY, 2007,18:3,320-335 p 320

- ↑ Judy Lattas Cruising: 'Moral Panic' and the Cronulla Riot THE AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF ANTHROPOLOGY, 2007,18:3,320-335 p 326

- ↑ Tim Flannery; The Explorers; Text Publishing 1998

- ↑ Lewis, Balderstone and Bowan (2006) p. 37

- ↑ "SBS.com.au". SBS.com.au. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ↑ Geoffrey Blainey; A Very Short History of the World; Penguin Books; 2004; ISBN 978-0-14-300559-9

- ↑ (1) The Fatal Confrontation: Early Native-White Relations on the Frontiers of Australia, New Guinea, and America: A Comparative Study Author(s): Wilbur R. Jacobs Source: The Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 40, No. 3 (Aug. 1971), pp. 283–309 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3638359 (1) 297

- ↑ "History & Heritage". Archived from the original on 9 April 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ↑ Gregson, Sarah. 'It all started on the mines'?: The 1934 Kalgoorlie race riots revisited. [online]. Labour History, no.80, May 2001: p23.

- ↑ Gregson, Sarah. 'It all started on the mines'?: The 1934 Kalgoorlie race riots revisited. Labour History, no.80, May 2001: p24.

- ↑ Schaper, Michael. The Broome race riots of 1920 [online]. Studies in Western Australian History, no.16, 1995: (112)-132. Availability: ISSN 0314-7525. [cited 22 Jul 09].

- ↑ Bowden, Tracy (15 July 2002). "Ethnicity linked to brutal gang rapes". ABC. http://www.abc.net.au/7.30/content/2002/s607757.htm Archived 8 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- ↑ 5• ^ a b Devine, Miranda (13 July 2002). "Racist rapes: Finally the truth comes out". The Sydney Morning Herald. http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2002/07/13/1026185124700.html. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- ↑ "In Pictures – In pictures: Australia violence". BBC News. 12 December 2005. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ↑ Liz Jackson (presenter) (13 March 2006). "Riot and Revenge". Four Corners. Season 2006. ABC. Archived from the original on 2 January 2010. Transcript: Program Transcript. Retrieved 25 December 2009.

- ↑ "Strike Force Neil, Cronulla Riots, Review of the Police Response Media Component Volume 2 of 4" (PDF). Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- ↑ "Strike Force Neil, Cronulla Riots, Review of the Police Response Media Component Volume 3 of 4" (PDF). Australian Broadcasting Corporation. pp. 7–20. Retrieved 24 December 2009.

- ↑ "Mob violence envelops Cronulla". The Sydney Morning Herald. Australian Associated Press. 11 December 2005. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ↑ "Mob mentality shameful: Police Commissioner". ABC News Online. 11 December 2005. Archived from the original on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ↑ The term white in this context typically refers to Australian people of West European ancestry whose first language is English, see White people.

- ↑ Braithwaite, David (26 May 2006). "I felt knife snapped off in my back". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 31 August 2006.

- ↑ "Actions more than stupid: magistrate", The Sydney Morning Herald, 24 January 2006

- ↑ "Insights - Uniting Church magazine online". Archived from the original on 19 October 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ↑ "Once Upon a Time in Punchbowl". Al Jazeera. 27 February 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

Exploring issues of integration, racism and multiculturalism, the four-part documentary series Once Upon a Time in Punchbowl looks to the past of an Arab community, the Lebanese in Australia – tracing the history of this community, their search for an identity, and their struggle to be accepted as Australians.

- ↑ "Study in Australia". Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ↑ "Only 23 of 152 Oz attacks racist, Ministry tells LS". The Indian Express. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ↑ "Australian Institute of Criminology – Executive summary". Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ↑ "Australian Institute of Criminology – National summary of findings". Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ↑ "Studies show most Indian students in Australia feel safe". Thaindian News. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ↑ "18 Indian protesters detained; taxi-driver fresh victim in Oz". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 29 September 2012.

- ↑ Jensen, Erik (10 June 2009). "Indians rally as suburb seethes". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ↑ Kent, Paul (10 June 2009). "Harris Park – tensions in a racial melting pot". The Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ Australian envoy admits attacks on Indians racist: IBN Live

- ↑ Katie Simmons and Amanda Lecouteur Modern racism in the media: constructions of 'the possibility of change' in accounts of two Australian 'riots'. P 668

- ↑ "Who Watches the Media? Race-related reporting in Australian mainstream media". All Together Now. December 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ↑ "Tribunal rules Alan Jones incited hatred". ABC News. 2 October 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ↑ Kontominas, Bellinda (1 February 2010). "Defendant must give victim $130,000". The Sydney Morning Herald.

Further reading

- Rubinstein, W. D.Anti/ Semitism in Australia. – Edited version of submission to the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission hearing on racial violence in Australia, 1989– Australian Jewish News, 13 Oct 1989: 16

- Lynching to Belong: Claiming Whiteness through Racial Violence. BUCKELEW, RICHARD A. 1 Journal of Southern History May 2009, Vol. 75 Issue 2, pp. 473–474

- The class issues behind Australia's race riots: [The racist violence that exploded in the Sydney suburb of Cronulla on 11 December 2005] Author: Socialist Equality Party (Australia)World Socialist Web Site Review, no.17, Feb–May 2006: 40–43

- Bowden, Tracy (15 July 2002). "Ethnicity linked to brutal gang rapes". ABC. 7.30 Report – 15/07/2002: Ethnicity linked to brutal gang rapes. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- Devine, Miranda (13 July 2002). "Racist rapes: Finally the truth comes out". Sydney Morning Herald. Racist rapes: Finally the truth comes out. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- Poynting, Scott. What caused the Cronulla riot? Race & Class, Vol. 48 Issue 1, pp. 85–92

- Chaper, Michael. The Broome race riots of 1920 [online]. Studies in Western Australian History, no. 16, 1995: (112)–132

External links

- "Once Upon a Time in Punchbowl", SBS (for Al Jazeera) produced four-part documentary series, looks to the past of an Arab community, the Lebanese in Australia, tracing the history of this community, their search for an identity, and their struggle to be accepted as Australians