Ramadan ibn Alauddin | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1312 or January 1313[lower-alpha 1] Korea? |

| Died | 11 April 1349 (aged 36–37) |

| Nationality | Goryeo |

| Other names | 剌馬丹 Lámǎdān |

| Occupation | Darughachi |

| Known for | Being the first named Muslim from Korea |

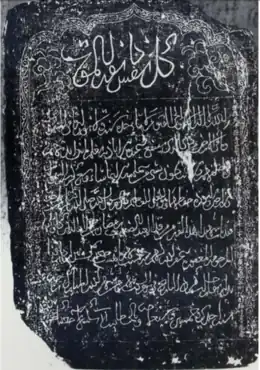

Ramadan ibn Alauddin (1312―April 11, 1349, رمضان ابن علاء الدين Ramaḍān ibn Alāʼ ud-Dīn) was a Yuan darughachi (governor) of Luchuan Prefecture in Rongzhou, Guangxi Province, of Muslim faith and Korean provenance. He served until his death in 1349. His existence is known only from an epitaph in the cemetery of the Huaisheng Mosque in Guangzhou. Ramadan is notable for being the first named Muslim from Korea,[2][3] although it is unclear whether he was of Korean ethnicity.

Historiography and popularization

The first academic publication to discuss Ramadan, a Muslim from fourteenth-century Korea, was a 1989 paper about Islamic epitaphs at Guangzhou by the Chinese historians Yang Tang and Jiang Yongxing.[4] The existence of Ramadan became popularized in South Korea in 2005, when the daily newspaper Hankook Ilbo published a story about Son Sang-ha, then ambassador-at-large of the country, visiting Guangzhou to see a replica of Ramadan's epitaph.[4] In 2006, KBS, South Korea's national public broadcaster, produced a documentary about Islam in medieval Korea centering on Ramadan.[5]

Epitaph

The life of Ramadan is known only from his epitaph in the cemetery of the Huaisheng Mosque in Guangzhou, China, originally located close to the grave said to be of Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas, a Companion of the Prophet Muhammad believed to have died in China. The epitaph has currently been moved inside the Huaisheng Mosque building.[6] The text is bilingual, with Arabic in the center and Classical Chinese written in small characters in the margins.[7]

The Arabic inscription is typical of Islamic funerary epitaphs. It uses a phrase from the Quranic verse 3:185, "Every soul will taste death," as its title. The inscription continues with the well-known Throne Verse, quoted in full, then adds a few details about Ramadan himself:[8]

The Messenger of God said long ago, "He who dies in a foreign land dies as a martyr."[lower-alpha 2]

This grave is where Ramaḍān ibn Alāʼ ud-Dīn, having died, has returned. May God forgive him and have mercy upon him and [illegible].

[illegible] who has visited Aleppo writes in the date of Rajab [illegible] in the year 751, blessed by God.[9]

The accompanying Chinese text gives Ramadan's address, occupation, and dates of death and burial.

Ramadan [剌馬丹 Lámǎdān], occupant of Qingxuangguan at Wanping Prefecture in Dadu Circuit, was a Korean. He was thirty-eight years old[lower-alpha 3] and had then been appointed as darughachi at Luchuan Prefecture in Rongzhou, Guangxi Province. He passed away on the twenty-third day of the third month of the ninth year of Zhizheng [April 11, 1349]. He was buried on the eighteenth day of the eighth month [September 30] at Guihuagang by the Liuhua Bridge at Chengbei, Guangzhou [location of the Muslim cemetery]. An epitaph was raised.[10]

According to the Chinese text, Ramadan died in April 1349, but was buried in the current location of his grave only in September. The Islamic month Rajab 751 AH, which the Arabic text is dated to, corresponds to September 1350 CE,[lower-alpha 4] a full year later. It thus appears that the grave's current location is the result of a reburial, and that the current epitaph was itself written a year after the reburial.[1]

Identity

Ramadan appears to have been a figure of some prominence. Not only did he serve as a darughachi or provincial governor for the Mongol Yuan dynasty that then ruled China, he had a residence near Dadu (modern Beijing), the Yuan imperial capital. He was also considered sufficiently important by the local Muslim community to be reburied near Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas, the legendary founder of Islam in China, and to be commemorated by a personally signed epitaph including multiple Quranic verses.[11]

Whether Ramadan was ethnically Korean is unknown.[6] After the Mongol conquest of Korea in the thirteenth century, many Central Asian Muslims (called semu) entered the country—then ruled by the Goryeo dynasty as Mongol vassals—to serve in the Mongol and Korean administrations or to engage in commerce. These Muslims established a local community in the Korean capital of Kaegyong, where they constructed a mosque and enjoyed significant cultural and religious autonomy until a royal decree ordering forcible assimilation was passed in 1427.[12] As the Mongols frequently appointed semu but rarely ethnic Koreans as local governors, Ramadan may have been a Muslim of Central Asian (perhaps Uyghur) ethnicity who was simply born or had settled in Korea. As Rongzhou was a center of trade with Trần Vietnam, historian Lee Hee-soo speculates that Ramadan may have been an international semu merchant based in Korea who was hired by the Yuan.[13]

On the other hand, Ramadan's residence was at Wanping Prefecture, a suburb of Dadu where there was a large ethnic Korean diaspora community in the fourteenth century. The Mongols sometimes classified Koreans as semu as well and occasionally did appoint them as officials and governors. It is thus possible that Ramadan was an ethnic Korean who (or whose father) had converted to Islam and adopted a Muslim name.[2][14]

Notes

- ↑ The epitaph states that Ramadan was thirty-eight in East Asian age reckoning in April 1349, meaning that he was born between 8 February, 1312, and 27 January, 1313. Lee Hee-soo speculates that his name may imply that he was born in the holy month of Ramadan, which was between 31 December, 1312 and 29 January, 1313 (for AH 712).[1]

- ↑ A hadith or saying of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad; considered da'if ("weak") in Book 6, entry 1681 of the collection Sunan ibn Majah.

- ↑ In East Asian age reckoning

- ↑ 4 September to 3 October, 1350

References

Citations

- 1 2 Lee H. 2007, p. 70.

- 1 2 Kim J. 2011, p. 208.

- ↑ Park H. 2004, p. 310.

- 1 2 Lee H. 2007, p. 67.

- ↑ Lee H. 2007, p. 68.

- 1 2 Lee H. 2007, p. 66.

- ↑ Park H. 2004, pp. 317–318.

- ↑ Lee H. 2007, pp. 68–70.

- ↑ "'하느님의 선지자가 일찍이 말하기를 타향에서 죽은 자는 이미 순교자가 되었다.' 이 묘는 알라우딘의 자식 라마단이 죽어 귀속된 곳이다. 하느님께서 그를 용서해주시고 자비를 구하여[缺] 할렙을 여행한 아르사[缺]이 하느님 축복받은 751년 7월 [缺]일에 쓴다." Park H. 2004, p. 318

- ↑ "大都路 宛平縣 靑玄關 주인 刺馬丹은 고려 사람이다. 나이는 38세이고 지금 廣西道 容州 陸川縣 達魯花赤에 임명되었다. 지정 9년 3월 23일에 몰하다. 8월 18일에 광주 城北 流花橋 桂花崗에 묻고 비석을 세우다." Park H. 2004, p. 319

- ↑ Lee H. 2007, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Lee H. 2007, pp. 74–77.

- ↑ Lee H. 2007, pp. 76–78.

- ↑ Park H. 2004, pp. 319–320.

Works cited

- 김정위 (Kim Jong-wee) (2011). "Goryeo-mal Hoegol-in-ui gwihwa-wa Iseullam-ui Han-bando deungjang" 고려말 回鶻人의 귀화와 이슬람의 한반도 등장 [The assimilation of Uyghurs and the appearance of Islam in the Korean peninsula during the late Goryeo]. 백산학보. 91: 177–241. ISSN 1225-7109. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- 박현규 (Park Hyun-kyu) (2004). "Choegeun balgul-doen Jungguk sojang Haedong gwallyeon geumseongmun: Goryeo-in Isseullam-gyodo Ramadan myobi" 최근 발굴된 중국 소장 海東 관련 금석문: 고려인 이슬람교도 剌馬丹 묘비 [A recently discovered Korea-related inscription in China: The epitaph of Ramadan, a Korean Muslim]. 중국학논총. 17: 309–324. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- 이희수 (Lee Hee-soo) (2007). "Jungguk Gwangjeou-eseo balgyeon-doen Goryeo-in Ramadan bimun-e daehan han haeseok" 중국 광저우에서 발견된 고려인 라마단 비문에 대한 한 해석 [An interpretation of the epitaph of Ramadan, a man of Goryeo, discovered in Guangzhou, China]. 한국이슬람학회논총. 17 (1): 63–80. ISSN 1226-2811. Retrieved 8 June 2020.