| Rebbachisaurids Temporal range: Late Jurassic to Late Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

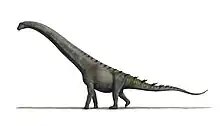

| Limaysaurus tessonei skeleton restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Superfamily: | †Diplodocoidea |

| Clade: | †Diplodocimorpha |

| Family: | †Rebbachisauridae Bonaparte, 1997 |

| Subgroups | |

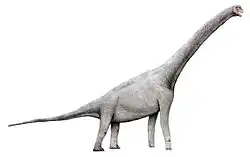

Rebbachisauridae is a family of sauropod dinosaurs known from fragmentary fossil remains from the Cretaceous of South America, Africa, North America, Europe and possibly Central Asia.

Taxonomy

In 1990 sauropod specialist Jack McIntosh included the first known rebbachisaurid genus, the giant North African sauropod Rebbachisaurus, in the family Diplodocidae, subfamily Dicraeosaurinae, on the basis of skeletal details. With the discovery in subsequent years of a number of additional genera, it was realised that Rebbachisaurus and its relatives constituted a distinct group of dinosaurs. In 1997 the Argentine paleontologist José Bonaparte described the family Rebbachisauridae, and in 2011 Whitlock defined two new subfamilies within the group: Nigersaurinae and Limaysaurinae. The cladogram of the Rebbachisauridae according to Carballido et al. (2012) is shown below:[3]

| Rebbachisauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cladogram after Fanti et al., 2015.[4]

| Rebbachisauridae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Evolutionary relationships and characteristics

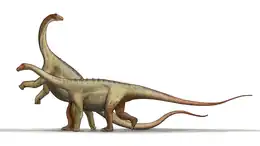

Although all authorities agree that the rebbachisaurids are members of the superfamily Diplodocoidea, they lack the bifid (divided) cervical neural spines that characterise the diplodocids and dicraeosaurids, and for this reason are considered more primitive than the latter two groups. It is not yet known whether they share the distinctive whip-tail of the latter two taxa.

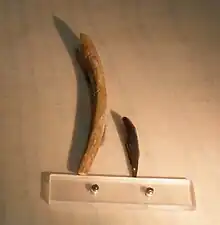

Rebbachisaurids are distinguished from other sauropods by their distinctive teeth, which have low angle, internal wear facets and asymmetrical enamel.

Unique among sauropods, at least some rebbachisaurids (such as Nigersaurus) are characterised by the presence of tooth batteries, similar to those of hadrosaur and ceratopsian dinosaurs. Such a feeding adaptation has thus developed independently three times among the dinosaurs.

So far, rebbachisaurids are known only from the middle and early part of the Late Cretaceous. They constitute the last known representatives of the dipldocoids, and lived alongside the titanosaurs until fairly late in the Cretaceous.

References

- Bonaparte J.F. (1997). "Rayososaurus agrioensis Bonaparte 1995". Ameghiniana. 34 (1): 116.

- McIntosh, J. S., 1990, "Sauropoda" in The Dinosauria, Edited by David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, and Halszka Osmólska. University of California Press, pp. 345–401.

- Upchurch, P., Barrett, P.M. and Dodson, P. 2004. "Sauropoda". In The Dinosauria, 2nd edition. Weishampel, Dodson, and Osmólska (eds.). University of California Press, Berkeley. pp. 259–322.

- Wilson J.A. (2002). "Sauropod dinosaur phylogeny: critique and cladistic analysis" (PDF). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 136 (2): 215–275. doi:10.1046/j.1096-3642.2002.00029.x.

- ------ (2005) "Overview of Sauropod Phylogeny and Evolution", in The Sauropods: Evolution and Paleobiology

- Wilson, J. A. and Sereno, P.C. (2005) "Structure and Evolution of a Sauropod Tooth Battery" in The Sauropods: Evolution and Paleobiology in Curry Rogers and Wilson, eds, 2005, The Sauropods: Evolution and Paleobiology, University of California Press, Berkeley, ISBN 0-520-24623-3

- ↑ Paul C. Sereno, Jeffrey A. Wilson, Lawrence M. Witmer, John A. Whitlock, Abdoulaye Maga, Oumarou Ide, Timothy A. Rowe (2007). Kemp, Tom (ed.). "Structural Extremes in a Cretaceous Dinosaur". PLOS ONE. 2 (11): e1230. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2.1230S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001230. PMC 2077925. PMID 18030355.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Lerzo, Lucas Nicolás; Gallina, Pablo Ariel; Canale, Juan Ignacio; Otero, Alejandro; Carballido, José Luis; Apesteguía, Sebastián; Makovicky, Peter Juraj (2024-01-03). "The last of the oldies: a basal rebbachisaurid (Sauropoda, Diplodocoidea) from the early Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian–Turonian) of Patagonia, Argentina". Historical Biology: 1–26. doi:10.1080/08912963.2023.2297914. ISSN 0891-2963.

- ↑ Carballido, José Luis; Salgado, Leonardo; Pol, Diego; Canudo, José Ignacio; Garrido, Alberto (2012). "A new basal rebbachisaurid (Sauropoda, Diplodocoidea) from the Early Cretaceous of the Neuquén Basin; evolution and biogeography of the group". Historical Biology. 24 (6): 631–654. doi:10.1080/08912963.2012.672416. S2CID 130423764.

- ↑ Fanti, F.; Cau, A.; Cantelli, L.; Hassine, M.; Auditore, M. (2015). "New Information on Tataouinea hannibalis from the Early Cretaceous of Tunisia and Implications for the Tempo and Mode of Rebbachisaurid Sauropod Evolution". PLOS ONE. 10 (4): e123475. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1023475F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0123475. PMC 4414570. PMID 25923211.