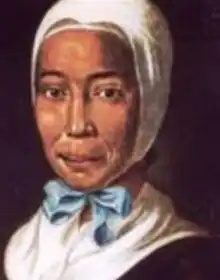

Rebecca Freundlich Protten | |

|---|---|

Rebecca Freundlich Protten | |

| Born | Shelly 1718 |

| Died | 1780 (aged 61–62) |

| Nationality | Danish subject |

| Occupation | Missionary |

| Known for | Mother of Modern Missions in the Atlantic World |

| Spouses |

|

| Children |

|

Rebecca Freundlich Protten, also Shelly (1718–1780) was a Caribbean Moravian evangelist and pioneer missionary who proselytized the Gospel to enslaved Virgin Islanders of Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands.[1][2][3][4] A "mulatress" and a former enslaved Antiguan, Antigua and Barbuda, she pioneered Christian missions in the Atlantic World in the 1700s.[5][6] Scholars have described her as the "Mother of Modern Missions" as her life's work bridged Christianity in the West Indies, in Europe and in West Africa, all geographic regions she lived in.[7][8][9][10][11]

Biographical sketch

Historical synopsis

Rebecca Protten was born enslaved in 1718 and gained her freedom as an adolescent. As a free woman of mixed European and African descent who lived on the island of St. Thomas during the 1730s, she joined the movement to convert enslaved Africans to Christianity. She became one of the first ordained African American women in Western Christianity.

Sources are unclear as to the location or circumstances of Rebecca's birth, but some note that she was originally kidnapped from Antigua.[12] She was then sold to a planter on St. Thomas named Lucas van Beverhout, who put her to work in his house as a servant and taught her the Christianity of the Reformed Church. Shortly after the death of Lucas van Beverhout when she was twelve, the Beverhout family freed Rebecca.

Religion played a central role in Rebecca's life after her enslavement. Even though she was free, opportunities were still minimal for her on St. Thomas. Then Christianity missionaries from the Unity of the Brethren, often called the Moravian Brethren, arrived on St. Thomas in 1732 as part of the Church's mission to convert the nations of the world to Christianity. The beginning of their ministry opened up new possibilities for Rebecca.[13] She became a leader in converting enslaved Africans, whose religious practices were constantly challenged by enslavers fearful of a united revolt.[14]

In 1742, Rebecca left St. Thomas with several Moravian missionaries, traveling to their home in Herrnhut, Saxony. There, she met and married Christian Protten in 1746. Protten was similarly noted for his mixed African and European descent. Protten, pursuing his life dream, journeyed to Christiansborg, a Danish fort on the Gold Coast, in an attempt to start a school but failed, returning six years later in 1762 to Herrnhut—the town founded by the first Moravian exiles and the headquarters of the movement, in which many of the Brethren lived.[12] Protten and Rebecca returned together to Christiansborg in 1763, where they spent the rest of their lives teaching African children. Rebecca Protten died in 1780.[12]

Unlike many other sects of Christianity, women were essential to the fabric of the Moravian church. This allowed Protten to participate in the church almost equally with men.[15] The Moravian Brethren's belief that men and women were spiritually equal in the eyes of God paved the path for Protten to become a preacher. She was named a deaconess a few weeks after her wedding.[16]

Early life

Rebecca Freundlich Protten was born a slave in 1718 in Antigua on the Caribbean island of Antigua and Barbuda.[1][2] The "Atlantic Creole" daughter of an African woman and a European, possibly a Dutchman, she was given the name "Shelly" by her master.[2][8] As a child, at the age of six or seven, she was kidnapped from Antigua and sold into slavery on the island of Saint Thomas, US Virgin Islands which was then a Danish sugar colony in the West Indies.[1][17] Shelly was converted to Christianity by her new Dutch Reformed master, baptised by a Roman Catholic priest and given the Christian name, Rebecca.[5][17] Eventually, Rebecca Protten gained her freedom. Subsequently, she used her liberation from bondage to share the Gospel of Jesus Christ with other enslaved people under the auspices of the Moravian Church of Germany, whose European missionaries taught her how to read and write.[1][7][8]

Work

West Indies

Rebecca partnered with Moravians in Saint Thomas and, buoyed by religious fervor, proselytized and converted hundreds and, most likely, thousands of people, mainly the enslaved.[1][7] In a hostile environment of persecution from enslavers and violence against enslaved people and missionaries, her direct method of itinerant evangelism was to trek "daily along rugged roads through the hills in the sultry evenings after the slaves had returned from the fields."[1][3][7][8] The colonial authorities in Saint Thomas were generally opposed to the practice and spread of the Christian faith in the slave segments of society. Given the external circumstances, the Moravian missionaries permitted her to teach women in informal settings only and prohibited public preaching.[7] In this period, there were approximately 5000 enslaved people in the Danish West Indies.[18]

She became a spiritual mentor to enslaved people who often came to her for guidance.[1][3][7][8] It is said that "she taught at a church that held popular nightly meetings at the end of a rugged road through the hills of St. Thomas known to the enslaved as 'The Path.'" "[1][3][7][8] Her mission sojourns "took her to the slave quarters deep in the island's plantation heartland, where she proclaimed salvation to the domestic servants, cane boilers, weavers, and cotton pickers whose bodies and spirits were strip-mined every day by slavery." Saint Thomas, therefore, became the axis of African Protestantism in the Americas.[1][3][7][8]

She then reached out to the German Moravian missionary, Friedrich Martin, who arrived in Saint Thomas in 1736 when she was about eighteen. He taught her that the Moravian movement encouraged and empowered women preachers. Impressed by the effectiveness of Rebecca's missionary work and evangelistic zeal, Martin noted that she was "very accomplished in the teaching of God. She has done the work of the Saviour by teaching African women and speaking about that which the Holy Spirit himself has shown her ... I have found nothing in her other than a love of God and his servants." [7] In the view of scholars Sylvia Frey and Betty Wood, the founding and growth of African Protestant Christianity was a watershed moment in the history of proselytism in the American South and the British colonies of the West Indies in the 1700s. This development "created a community of faith and ... provided Afro-Atlantic peoples with an ideology of resistance, [as part of paradigm shift] of social and intellectual transformation transference of traditional African religions to the New World."[3][7]

Together with her Moravian husband, she was accused and charged by the colonial authorities for blasphemy and accusations of incitement of a slave rebellion or an insurrection and imprisoned.[1][3][7][8] They were deported after their release.[1][3][7][8]

Western Europe

In 1742, she left Saint Thomas and relocated to Germany with the Moravian missionary Friedrich Martin, her first husband, Matthäus Freundlich (c. 1681–c. 1742) and their daughter, Anna Maria Freundlich (1740–1744).[1][3][7][8] Soon after docking in Amsterdam in 1742, Friederich Martin was called back to the St. Thomas mission, because his replacement for Head of the Moravian mission there had died.[8] Rebecca Freundlich's husband and daughter died in Germany.[1][3][4][7][8][19] With nowhere else to go and little point of reference in a faraway land, Rebecca Freundlich was taken by friends to the commune owned by the leader of the Moravian church, Nikolaus Ludwig, Reichsgraf von Zinzendorf und Pottendorf (1700–60), in Germany.[1][20][21] While living in Germany, she became a valued member of the Moravian community. She assumed a leadership position in the women's Christian ministry.[1][8]

Historians have emphasized that in everyday religious life in 18th-century Moravia, "Choirs were the basic social units of the church ... Believers were expected to submerge their own desires in the will of the group. Choir members ate and bunked together, often worked side by side, and met at least once a day, often more, to worship and decipher religious texts."[8]

In 1756, Rebecca Freundlich Protten and her second husband, Christian Jacob Protten (1715–1769), were marginalized and banished from the Moravian commune in Herrnhut to the village of Großhennersdorf in the Görlitz district.[22] This development stemmed from constant bickering between Christian Protten and the Bishop of the Moravian Church, Count Zinzendorf. Zinzendorf had accused Christian Protten of being haughty and an alcoholic.[22] He received permission to return to West Africa, leaving his Rebecca Protten, who rejoined the Moravians at Herrnhut.[22]

West Africa

In 1765, Rebecca Protten arrived on the Gold Coast for the first time.[20][21][22] With the blessing of the Moravian church, her husband became the schoolmaster of the Christiansborg Castle School for mulattoes, serving until he died in 1769. Rebecca Protten became widowed for a second time. At this point, she had not fully acclimatized to the Gold Coast. The Moravian missionaries contemplated and sought her return to Saint Thomas.[20][21][22] As she was in poor health, it was ultimately decided she remained on the Gold Coast, where she eventually died in 1780.[20][21][22]

Personal life

On 4 May 1738, Rebecca married Matthaus Freundlich (c. 1681-c. 1742), a German Moravian missionary on Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands.[1][2][4][19] Rebecca Freundlich had an arranged marriage to Matthaus Freundlich.The Freundlichs had a daughter, Anna Maria Freundlich, born circa 1740, in Saint Thomas. Anna Freundlich died in 1744, aged four years, in Germany.[1][2][4][19] The Freundlich family had traveled to Germany due to Matthaus Freundlich's ill-health, even as they were persecuted by slave plantation owners, and imprisoned for their Christian faith while they shared the Gospel to enslaved Virgin Islanders in Saint Thomas.[1][2][4][19] Matthaus Freundlich however died during the trip across Germany.[1][2][4][19] On 6 June 1746, she remarried, to Christian Jacob Protten (1715–1769), a Gold Coast Euro-African educator and missionary in Herrnhut Germany.[4][19][20][21][22][23][24][25] The first recorded grammatical treatise in the Ga and Fante languages were written by Protten and published under the title, "En nyttig Grammaticalsk Indledelse til Tvende hidintil gandske ubekiendte Sprog, Fanteisk og Acraisk," in Copenhagen in 1764.[26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34] In 1750, Christian and Rebecca Protten had a daughter, Anna Maria Protten, who died in infancy in Herrnhut, Dresden in Sachsen, Germany.[1][4][19]

Death and legacy

Rebecca Freundlich Protten died in 1780, aged 62, in Christiansborg, Accra, on the Gold Coast.[1][2][4][8][19] Commenting on her legacy, her biographer, Jon F. Sensbach, author of "Rebecca's Revival- Creating Black Christianity in the Atlantic World," [1][7] noted Rebecca Freundlich Protten was

"a prophet, [with a] distinctively international persona—obedient to a calling, yet adept at negotiating life's possibilities, resourceful in any setting or language, [and] determined to take what she regarded as the Bible's liberating grace to people of African descent ... Much that we associate with the black church in subsequent centuries—the anchor of community life, advocate for social justice, midwife to spirituals and gospel music—in some measure derives ... from those early origins ... Though hardly anyone knows her name today, Rebecca helped ignite fires of a new kind of religion that in subsequent centuries has given spiritual sustenance to millions."

Rebecca Freundlich Protten became an exemplar of using the Christian mission as a tool for the emancipation of African people.[8]

Biographies

The life of Rebecca Protten was looked at first extensively by Christian Oldendorp, a Moravian missionary who admired Rebecca's evangelical work, which he noted in History of the Mission of the Evangelical Brethren on the Caribbean Islands of St. Thomas, St. Croix, and St. John.[35] historian Jon F. Sensbach recently wrote a biography on Rebecca Protten, Rebecca's Revival. Sensbach focused on how Protten became the leader of the African Christianity movement.[36] Rebecca Freundlich Protten also received mention in Time Longa' Dan Twine, written in 2009 by Arnold R. Highfield.[12]

Literature

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Sensbach, Jon F. (30 June 2009). Rebecca's Revival. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674043459. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Sensbach, Jon F. (2006). Rebecca's Revival. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674022577. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Frey, Sylvia R.; Wood, Betty (9 November 2000). Come Shouting to Zion: African American Protestantism in the American South and British Caribbean to 1830. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807861585. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Rebecca Protten Freundlich". geni_family_tree. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- 1 2 Sopiarz, Josh (31 July 2006). "Rebecca's Revival: Creating Black Christianity in the Atlantic World (review)". Eighteenth-Century Studies. 39 (4): 573–574. doi:10.1353/ecs.2006.0031. ISSN 1086-315X. S2CID 162115295.

- ↑ Carretta, V. (1 June 2006). "JON F. SENSBACH. Rebecca's Revival: Creating Black Christianity in the Atlantic World. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. 2005. Pp. 302. $22.95". The American Historical Review. 111 (3): 794–795. doi:10.1086/ahr.111.3.794. ISSN 0002-8762.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Meet the Mother of Modern Missions". The Gospel Coalition. Archived from the original on 31 October 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 "The Limits of Rebecca's Revival". khronikos: the blog. 9 May 2013. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ↑ "Rebecca's Revival — Jon F. Sensbach | Harvard University Press". www.hup.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ↑ Sasser, Daryl (December 2005). "Review of Sensbach, Jon F., Rebecca's Revival: Creating Black Christianity in the Atlantic World". www.h-net.org. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ↑ "Rebecca Protten | People/Characters | LibraryThing". www.librarything.com. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Highfield, Arnold. Time Longa' Dan Twine, 2009, Antilles Press, USVI, ISBN 978-0-916611-23-1

- ↑ Sensbach, Jon. F (2005). Rebecca's Revival: Creating Black Christianity in the Atlantic World. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 45.

- ↑ Hempton, David (2011). The Church in the Long Eighteenth Century. New York: I.B.Tauris & Co. p. 84.

- ↑ Sensbach, Jon. F (2005). Rebecca's Revival: Creating Black Christianity in the Atlantic World. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 47.

- ↑ Hempton, David (2011). The Church in the Long Eighteenth Century. New York: I.B Tauris & Co. p. 85.

- 1 2 "Rebecca Protten: How a Formerly Enslaved Woman Impacted Christianity". Faithfully Magazine. 12 September 2018. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ↑ "Slave Voyages". Archived from the original on 27 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Christian Jakobus Protten". geni_family_tree. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Smith, Noel. "Christian Jacob Protten". dacb.org. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dreydoppel, Otto. "Christian Jacob Protten". dacb.org. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "This Month in Moravian History: Christian Protten - Missionary to the Gold Coast of Africa" (PDF). Moravian Archives. Bethlehem, PA. (74). June 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ↑ Sebald, Peter (1994). "Christian Jacob Protten Africanus (1715-1769) - erster Missionar einer deutschen Missionsgesellschaft in Schwarzafrika". Kolonien und Missionen. (in German): 109–121. OCLC 610701345.

- ↑ Simonsen, Gunvor (April 2015). "Belonging in Africa: Frederik Svane and Christian Protten on the Gold Coast in the Eighteenth Century". Itinerario. 39 (1): 91–115. doi:10.1017/S0165115315000145. ISSN 0165-1153. S2CID 162672218.

- ↑ Hutton, J. E. (1923). A History of Moravian Missions. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Debrunner, Hans Werner (1954). H. W. Debrunner. "Anfaenge Evangelischer Missionarbeit auf der Goldkueste bis 1828," Evangelisches Missions Magazin. Basel.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Steiner, P. (1888). Ein Blatt aus der Geschichte der Brudermission.

- ↑ Protten, Christian Jacob (1764). En nyttig Grammaticalsk Indledelse til Tvende hidintil gandske ubekiendte Sprog, Fanteisk og Acraisk. Copenhagen.

- ↑ Dietrich, Meyer (April 2011). "Lieberkühn, Samuel". Religion Past and Present. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ↑ Manuscript: Diarium of/by Christian Jakob Protten Africanus (1715-1769).

- ↑ Wilson, Armistead (1848). Tribute for the Negro. Manchester.

- ↑ Debrunner, Hans Werner (1967). A history of Christianity in Ghana. Waterville Pub. House. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018.

- ↑ Debrunner, Hans W. (1967). A history of Christianity in Ghana. Waterville Pub. House. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013.

- ↑ Debrunner, Hans W. (1967). A history of Christianity in Ghana. Accra: Waterville Pub. House. OL 4877755M.

- ↑ Arends, J (2004). "Christian Georg Andreas Oldendorp, 'Historie de caribischen Inseln Sanct Thomas, Sanct Crux and Sanct Jan, insbesondere der dasigen Neger and der Mission der evangelischen Bruder unter denselben', part 1". Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages. 19 1: 171–176. doi:10.1075/jpcl.19.1.10are.

- ↑ Sensbach, Jon F. (2005). Rebecca's Revival: Creating Black Christianity in the Atlantic World. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 3.