The Red Deer Cave people were a prehistoric population of modern humans known from bones dated to between about 17,830 to c. 11,500 years ago, found in Red Deer Cave (Maludong, Chinese: 马鹿洞) and Longlin Cave, Yunnan Province, in Southwest China.

The fossils exhibit a mix of archaic and modern features and were tentatively thought to represent a late survival of an archaic human species, or of a hybrid population of Denisovan hominin and modern human descent, or alternatively just "an unfortunate overinterpretation and misinterpretation of robust early modern humans, probably with affinities to modern Melanesians".[1] A partial genome sequence in 2022 established that, despite their morphologically unusual features, they were modern humans related to contemporary populations in East and Southeast Asia, as well as the Americas.[2]

Evidence shows large deer were cooked in the Red Deer Cave, giving the people their name.[3]

Discovery and dating

In 1979, petroleum geologist Li Changqing discovered a block of fine-grained sediments containing human remains, animal fossils, charcoal, and burnt clay from a cave near the town of De'e, Longlin County, Guangxi Province, China. These are categorised as belonging to a single specimen, LL-1. He promptly shipped them to Kunming in the neighbouring Yunnan Province for further study, whereupon a mandible (lower jawbone) and some body bones were extracted. In 1989, the Red Deer Cave near Mengzi City, Yunnan Province, was also excavated for human remains. The significance of these finds would not be realised until Darren Curnoe, Ji Xueping, and colleagues began dating and describing existing collections of East Asian human fossils to better evaluate the poorly documented Asian archaeological record in 2008. They found the Red Deer Cave and Longlin people feature a suite of modern and archaic traits, yet lived surprisingly recently. Charcoal remnants inside the braincase were dated using uranium–thorium dating to only 17,830–13,290 years ago for various Red Deer Cave human specimens, and 11,510 years ago for LL-1. They restarted excavation of Longlin Cave in 2008, and yielded a few more human fossils, but most of the known material from the cave was recovered in the initial dig. In 2010, they were able to remove the rest of the skull and body fossils from the Red Deer Cave block.[4]

The dating of the bones has led to confusion and division among researchers. The anatomy of the bones, prior to successful DNA testing, suggested they were archaic humans, like early Homo erectus or Homo habilis who lived around 1.5 million years ago in Africa.[5] In 2013, Curnoe, Ji, and colleagues hypothesised that the cave people possibly represented a new species.[6]

In 2015, Curnoe, Ji, and colleagues suggested the Red Deer Cave people represent a hybrid population between early modern humans and one or several unidentifiable native archaic species, since they bear a peculiar combination of archaic and modern features not exhibited in any other specimen. Modern humans may have entered China as early 130,000 years ago, as evidenced by the Zhirendong remains; though, owing to an unusual mosaic anatomy, the classification of such early specimens is debated.[7] Later that year, they concluded the femur is far outside the range of variation for a modern human (that the Red Deer Cave people must be archaic). They suggested they either represent the enigmatic Denisovans — a poorly known group of late-surviving Homo which was apparently dispersed across Asia, currently only identifiable by their genetic signature — or a long-removed lineage from an incredibly early dispersal of Homo out of Africa which had not evolved a characteristically human body plan, such as that represented by the Dmanisi hominins. The latter scenario has also been proposed for H. floresiensis, which survived rather recently as well, probably due to being isolated on the island of Flores. They speculated the Red Deer Cave people persisted for a similar reason, isolated in the mountains.[5]

Anatomy

In spite of their relatively recent age, the fossils exhibit archaic human features.[5] The Red Deer Cave dwellers had distinctive features that differ from modern humans, including: flat face, broad nose, jutting jaw with no chin, large molars, prominent brows, thick skull bones, and moderate-size brain.[1] As with some other pre-modern humans, their body size was small, with an estimated mass of 50 kg (110 lb).[8]

Curnoe's previous works showed the bones and teeth were remarkably similar to that of archaic humans.[5] The height of the mandibular symphysis at 27.7 mm (1.09 in) is within the range of modern humans, and the thickness at 12.5 mm (0.49 in) the range of Neanderthals and Middle Palaeolithic modern humans. The mental foramina (a hole in the mandible) is placed rather low at 26.9 mm (1.06 in) from the base, whereas modern humans and Neanderthals are normally above 30 mm (1.2 in). The height of the first two molars and the thickness at that level is nearly identical to Upper Palaeolithic Asians, but the molars themselves are proportionally quite broad like those of Neanderthals or Middle Palaeolithic humans.[6]

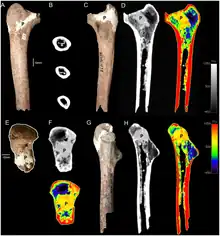

The Red Deer Cave femur is quite archaic, retaining some traits which have been lost in all anatomically modern humans. The subtrochanteric region (just below the lesser trochanter) is circular in cross-section and has a low total and cortical bone area, reducing resistance to axial (straight down) loads. The midshaft diameter is rather narrow, which could indicate the individual was short-statured. The femur also has a moderate pilaster value index (measuring the robustness of the linea aspera), notably lower than in anatomically modern humans. In sum, the femur recalls far earlier Lower Pleistocene Homo.[5]

The reconstruction of the Maludong femur confirmed it was very small with the outer shell, or walls, are very thin. The areas of the wall that were of high strain, and the femur neck, are relatively long; the place of muscle attachment for the primary flexor muscle of the hip (the lesser trochanter) was robust and faced strongly backward.[5]

Classification

There was much initial speculation that the Red Deer Cave people represent an archaic human lineage, though researchers proved reluctant to classify them as an otherwise unknown, or little-known, species.[1] The remains from Red Deer Cave bear morphological similarlities to archaic hominid lineages such as Homo erectus and Homo habilis.[8] In particular, the RDC specimen was seen as anatomically most similar in most of the characteristics to an individual known as KNM-ER 1481,[5] a member of H. erectus, who lived 1.89 million years ago in Africa.[9] The remains have been described as exhibiting some similarities to Australopithecus (i.e more than the genus Homo).[10] It was also suggested that they might have resulted from mating between Denisovans and anatomically modern humans (AMH),[3] or, alternatively that they were an AMH population with unusual physiology.[1]

One theory suggested that the Red Deer Cave people were early humans that settled into the region more than 100,000 years ago and became isolated.[11] The high mountains and deep valleys are ideal in isolating species geographically, so it is possible for a species to migrate to the area and become genetically isolated over time. The environment and climate of Southwest China are also unique owing to the tectonic uplift of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau.

The successful sequencing of ancient genomic DNA from the Red Deer Cave skull, reported in July 2022, showed that the skull belonged to an anatomically modern human population that was genetically affiliated to modern East Asians, as well as, to a lesser extent, Native American populations.[2] Additionally, this woman belonged to maternal haplogroup M9 - a genetic lineage that arose approximately 47,000-50,000 years ago, probably in South Asia.[2] [12]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Owen J (14 March 2012). "Cave Fossil Find: New Human Species or "Nothing Extraordinary"?". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on March 16, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Zhang, Xiaoming; Ji, Xueping; Li, Chunmei; Yang, Tingyu; Huang, Jiahui; Zhao, Yinhui; Wu, Yun; Ma, Shiwu; Pang, Yuhong; Huang, Yanyi; He, Yaoxi (July 2022). "A Late Pleistocene human genome from Southwest China". Current Biology. 32 (14): 3095–3109.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.06.016. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 35839766. S2CID 250502011.

- 1 2 Barras C (14 March 2012). "Chinese human fossils unlike any known species". New Scientist. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ↑ Curnoe, D.; Xueping, J.; Herries, A.I.; Kanning, B.; Taçon, P.S.; Zhende, B.; et al. (2012). Caramelli, David (ed.). "Human remains from the Pleistocene-Holocene transition of southwest China suggest a complex evolutionary history for East Asians". PLOS ONE. 7 (3): e31918. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...731918C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031918. PMC 3303470. PMID 22431968.

All of the [Maludong] human remains were recovered from within a series of deposits dating from 14,310±340 cal. yr BP (OZM149; 292 cm depth) to 13,590±160 cal. yr BP (OZM145; 166 cm depth), a period of about 720 years. Moreover, the high fine-grained ferrimagnetic content of the deposits (Text S1), with their high magnetic susceptibility, suggests these were formed under warm, wet conditions, consistent with the Bølling-Allerød interstadial (~14.7-12.6 ka). Human remains recovered in situ during the 2008 excavation and a reasonably complete calotte (specimen MLDG 1704) derived from a subsection of these deposits dated between 13,990±165 cal. yr BP (OZM148; 235 cm) and 13,890±140 cal. yr BP (OZM146; 200 cm)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Curnoe, Darren; Ji, Xueping; Liu, Wu; Bao, Zhende; Taçon, Paul S. C.; Ren, Liang (17 December 2015). "A Hominin Femur with Archaic Affinities from the Late Pleistocene of Southwest China". PLOS ONE. 10 (12): e0143332. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1043332C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143332. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4683062. PMID 26678851.

- 1 2 Ji, X.; Curnoe, D.; et al. (2013). "Further geological and palaeoanthropological investigations at the Maludong hominin site, Yunnan Province, Southwest China". Chinese Science Bulletin. 58 (35): 4472–4485. Bibcode:2013ChSBu..58.4472J. doi:10.1007/s11434-013-6026-5. hdl:10072/56357. S2CID 54625940.

- ↑ Curnoe D, Ji X, Taçon PS, Yaozheng G (July 2015). "Possible Signatures of Hominin Hybridization from the Early Holocene of Southwest China". Scientific Reports. 5 (1): 12408. Bibcode:2015NatSR...512408C. doi:10.1038/srep12408. PMC 5378881. PMID 26202835.

- 1 2 Curnoe D (18 December 2015). "Bone Suggests 'Red Deer Cave People' A Mysterious Species Of Human". IFLScience. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ↑ "KNM-ER 1481". The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program. 21 January 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ↑ Schwartz, J. (June 2016). "What constitutes Homo sapiens? Morphology versus received wisdom". Journal of Anthropological Sciences. 94 (94): 65–80. doi:10.4436/JASS.94028. PMID 26963221.

- ↑ Curnoe, Darren (17 December 2015). "Bone suggests 'Red Deer Cave people' a mysterious species of human". The Conversation. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ↑ Karafet TM, Mendez FL, Meilerman MB, Underhill PA, Zegura SL, Hammer MF (May 2008). "New binary polymorphisms reshape and increase resolution of the human Y chromosomal haplogroup tree". Genome Res. 18 (5): 830–8. doi:10.1101/gr.7172008. PMC 2336805. PMID 18385274.

External links

Media related to Red Deer Cave people at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Red Deer Cave people at Wikimedia Commons- Defining ‘human’ – new fossils provide more questions than answers (article by Darren Curnoe in The Conversation, March 15, 2012)

- Enigma Man: A Stone Age Mystery (Aired by ABC TV on Tuesday 24 June 2014, 8:30pm)

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).