.jpg.webp)

Maria Christina of Austria was regent of Spain from the death of her husband, Alfonso XII, in November 1885 until their son, Alfonso XIII, turned sixteen and swore the Constitution of 1876 in May 1902. Queen Maria Christina was pregnant when her husband died and gave birth to King Alfonso XIII in May 1886.

According to historian Manuel Suárez Cortina, "the Regency was a particularly significant period in the history of Spain, because in those years at the end of the century the system experienced its stabilization, the development of liberal policies, but also the appearance of great fissures that in the international arena were reflected first in the colonial war, and later with the United States, causing the military and diplomatic defeat that led to the loss of the colonies after the Treaty of Paris in 1898. In the domestic sphere, the Spanish society underwent a considerable mutation, with the appearance of such significant political realities as the emergence of regionalisms and peripheral nationalisms, the strengthening of a workers' movement of double affiliation, socialist and anarchist, and the sustained persistence, although decreasing, of the republican and Carlist oppositions".[1]

The death of Alfonso XII and the "pact of El Pardo"

On November 25, 1885, the young King Alfonso XII[2] died of tuberculosis and his wife Maria Christina of Austria assumed the regency, "a young woman, foreigner, with little time in Spain, not very popular and with a reputation of being not very intelligent".[3] In addition to the weakness in which the highest institution of the State seemed to be left, there was the fact that, while waiting for a third childbirth because the Queen was pregnant, there was no male heir —Alfonso and María Christina, married on November 29, 1879, had had two daughters—. Thus the death of Alfonso XII created a certain vacuum of power— Menéndez Pelayo wrote to Juan Valera who was in Washington: "The death of the king has produced here a singular stupor and uncertainty. No one can guess what will happen"—.[3] This could be taken advantage of by the Carlists or the Republicans to put an end to the Restoration regime.[4] In fact, in September 1886, only four months after the birth of Alfonso XIII, there was a republican uprising led by General Manuel Villacampa del Castillo and organized from exile by Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla, which constituted the last military attempt of republicanism and whose failure deeply divided it.[5]

To face the situation of uncertainty created by the death of the king and through the mediation of General Martínez Campos, the leaders of the two parties of the time, Antonio Cánovas del Castillo for the Conservative Party and Práxedes Mateo Sagasta for the Liberal-Fusionist Party, met to agree on the replacement of the former by the latter at the head of the government. The so-called "Pacto del Pardo" —although the interview took place in the seat of the Presidency of the Government and not in the Palacio del Pardo— included the "benevolence" of the Conservatives with respect to the new Liberal government of Sagasta. However, the faction of the Conservative Party headed by Francisco Romero Robledo did not accept the cession of power to the liberals and left the party to form one of its own, called the Liberal-Reformist Party, which was joined by José López Domínguez's Izquierda Dinástica, in an attempt to create an intermediate political space between the two parties of the turn.[6][7]

Cánovas del Castillo justified the Pact of El Pardo in the Congress of Deputies months later:[3]

The conviction was born in me that it was necessary for the fierce struggle that we monarchist parties were engaged in at the time... to cease in any case, and to cease for quite some time. I thought that a truce was indispensable and that all monarchists should rally around the Monarchy. [And once I had thought of this... what was it up to me to do? After having been in government for almost two years and having governed most of the reign of Alfonso XII, was it up to me to speak to the parties and tell them: 'because the country is in this crisis, do not fight me anymore; let us make peace around the throne; let me be able to defend and support myself? That would have been absurd and, besides being ungenerous and dishonest, it would have been ridiculous. Since I stood up to propose concord and to ask for a truce, there was no other way to make people believe in my sincerity but to remove myself from power.

In June, the various liberal factions had reached an agreement, known as the law of guarantees, which made it possible to reestablish the unity of the party. It had been drawn up by Manuel Alonso Martínez, representing the fusionists, and Eugenio Montero Ríos, representing the leftists, and consisted of developing the freedoms and rights recognized during the democratic Sexenio —universal suffrage, trial by jury and so on— in exchange for the acceptance of shared sovereignty between the king and the Parliament, on which the Constitution of 1876 was based, meaning that the last word in the exercise of sovereignty would be held by the Crown and not by the electorate. Left out of the liberal-fusionist party was the faction led by General López Domínguez, to whom Sagasta offered the ambassadorship in Paris, but he demanded a minimum of 27 deputies in the new Parliament, which was considered an excessive number.[8]

Sagasta's "Long Parliament" (1885–1890)

In April 1886, five months after forming the government and one month before the birth of the future Alfonso XIII, the liberals called elections to provide themselves with a solid majority in the Cortes and thus be able to develop their government program, although they had already been able to begin to implement it thanks to the benevolence of the conservatives. This period was called the Long Government of Sagasta or also the Long Parliament, since they were the longest lasting Cortes of the Restoration and the only ones that were about to exhaust their legal life, but it was not easy for Sagasta to keep his party and his government united, since during those five years he had to overcome several crises.[8]

During this period "a set of reforms were carried out that definitively configured the social and political profile of the Restoration as a historical epoch", which is why some historians have considered it the "most fruitful period" of the Restoration.[6]

Political and legal reforms

The first great reform of the Long Government of Sagasta was the approval in June 1887 of the Law of Associations which regulated freedom of association for the purposes of "human freedom" and which allowed workers' organizations to act legally, since it included trade union freedom, giving a great boost to the workers' movement in Spain. Under the protection of the new law, the anarcho-syndicalist FTRE, founded in 1881 as the successor to the FRE-AIT of the Sexenio Democrático, spread, and the socialist Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT) was born, founded in 1888, the same year in which the Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE), born in hiding nine years earlier, was able to hold its First Congress.[9]

The second major reform was the jury law, an old demand of progressive liberalism that had always been resisted by conservatism, and which was approved in April 1888. Trial by jury was established for those crimes that had the greatest impact on the maintenance of social order or that affected individual rights, such as freedom of the press. According to the law, the jury would be in charge of establishing the proven facts, while the legal qualification of the facts would correspond to the judges.[10]

The third major reform was the introduction of universal (male) suffrage by means of a law passed on June 30, 1890. However, the law was not the result of popular pressure in favor of the extension of suffrage, but what Sagasta achieved with its approval was to ensure the unity of the party and the government, satisfying a historical demand of democratic liberalism at a time when the pressure of the "gamacistas" was increasing in favor of approving a protectionist tariff for cereal production. A second reason was the strengthening of the liberal party —and of the Restoration regime— with the incorporation into it of Emilio Castelar's "posibilists" republicans, as they had promised if the extension of suffrage was approved.[11]

However, the approval of suffrage for all males over twenty-five years of age —some five million in 1890—, regardless of their income, as was the case with census suffrage, did not mean the democratization of the political system, because electoral fraud was maintained —thanks to the caciquismo, as it was said at the time—, only that now the cacique networks were extended to the whole population, so that the governments continued to be formed before the elections, and not after, since the government of the day was manufactured with the encasillado of a solid majority in the Parliament—during the Restoration no government ever lost an election—.[12]

According to Carlos Dardé, the ultimate reason for this "lack of mobilizing effects of universal suffrage in political life... was the social condition —economic and cultural— of the new voters, and their political horizon. The immense majority, male, to whom the right to vote had been given was not composed of middle and working classes of urban character, or independent peasants, involved in a political project of democratic character, but of rural masses, extremely poor and illiterate, completely alien to that project, with the hope of a social revolution, in the southern half of the country, and of the triumph of Carlism, in a good part of the north; masses which, in addition, had experienced either a strong police repression or the defeat in a civil war".[12]

Thus, "although formally it amounted to the establishment of democracy, [the approval of universal (male) suffrage] in practical terms nothing changed".[13] "The deputies remained, more or less, the same; no social group, with few exceptions, gained access to legislative power. Nor was there any transformation of the party structure, which continued to be parties of notables; no base organization was promoted to attract the vote of the citizens whose electoral rights had just been recognized".[12] Furthermore, the Constitution was not reformed, so the principle of national sovereignty was still not recognized, and only one third of the Senate was elected —the freedom of worship, another of the principles of a democratic system, was not recognized either—.[14]

On the other hand, the proof that the objective of the law was not the establishment of democracy was that no guarantees were adopted to ensure the transparency of the suffrage and thus avoid electoral fraud, such as the updating of the census by an independent body, the requirement of an accreditation to the person who was going to vote or the control of the whole process that remained in the hands of the Minister of the Interior, known as the "great elector", since he was the one who was in charge of ensuring that his government enjoyed a large majority in the Cortes. "The fact that in some urban centers the opposition was able to reverse this reality is almost a testimonial fact. Political control from above, the practice of the turn by means of electoral fraud is what constitutes the essence of the political practices of Spain at the end of the century", concludes Manuel Suárez Cortina.[15] A point of view that is shared by Carlos Dardé:[16] "In some cities —Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia...— things did indeed change, in favor of a modern politics, based on public opinion; as proof of this, Republican representation was more numerous and constant, sometimes reaching the majority of deputies elected by these large population centers; with the passage of time, the Socialists would also be elected; in Catalonia, the Nationalists managed to send a significant representation to Congress in Madrid; the same could be said of the Carlists in Navarre. But this representation of deputies was irremediably lost in the national assembly: of some 400 seats in Congress, the maximum number of Republican deputies was 36, in 1903, and that of Socialists, 7 in 1923". The electoral districts, all of them uninominal, continued to be the majority —280 deputies—, while the urban ones were linked to large rural areas since they were plurinominal districts or constituencies —114 in total— in which between three and eight deputies were elected, depending on the population, in such a way that the votes of the rural areas "drowned" the urban votes less controllable by the caciquial networks.[12]

A fourth reform was the approval in May 1889 of the Civil Code, which together with the Penal Code of 1870 and the Code of Commerce of 1885, definitively configured the "juridical edifice of the new bourgeois order", by sealing "in the private sphere what the Constitution had established in the public sphere". It included foral civil law and respected canon law with respect to marriage.[17]

However, the government failed in its attempt to reform the Army, whose situation "was, as a whole, very deficient in comparison with other national armies" because "rather than as an institution designed for war, it was organized for garrison and public order tasks, with poorly endowed troops, forced conscripts, with an excess of commanders and with an inadequate organizational structure". The ultimate cause of the failure was the autonomy enjoyed by the Army, which was the price that had to be paid for it to accept submission to civilian power, so that "any reform had to be approached with the acquiescence of the commanders. An extremely delicate task, since the situation of hypertrophy, the excess of officers, the poor equipment and the esprit de corps, based on a strong tradition of self-recruitment, had made the Armed Forces a reality that was not very permeable to external demands and controls". Thus, the bill presented by the Minister of War, General Manuel Cassola, in June 1887 was not approved by the Cortes due to the strong opposition it encountered among conservatives, starting with Cánovas himself, and among both conservative and liberal military members of parliament. One of the most controversial issues was the proposal to establish compulsory military service without redemptions or substitutions, which allowed the sons of wealthy families not to join the ranks if they paid a certain amount of money or sent a substitute in their place. In June 1888, General Cassola resigned and the government opted to impose by decree the less controversial parts of the law which had not been challenged by the Cortes: "it abolished honorary ranks, jobs higher than the effective one, mobility between arms with the exception of some special corps; it established promotion by seniority in peacetime and the possibility in wartime of voluntarily exchanging a promotion for merit with a medal".[18]

The strengthening of the workers' movement: FTRE, UGT and the refoundation of the PSOE.

Due to the slowness of the industrialization process, the working class continued to constitute a minority within the urban working classes —and continued to be concentrated fundamentally in Catalonia and in the mining areas of Vizcaya and Asturias—. In industry, or in the mines, work was hard and long. Around 1900 the average working day was 10–11 hours with an average wage of between 3 and 4 pesetas a day in factories and workshops, 3.25 to 5 pesetas in the mines, and 2.5 pesetas in construction.[19] As for the agricultural working class —or "rural proletariat"— low wages continued to make the farms profitable, so the day laborers continued to constitute the sector of the rural classes that lived in the worst conditions. Their wages were well below those of industrial workers —around 1900 they were 1 to 1.5 pesetas a day— and they did not work all year round. The situation was especially scandalous in the case of the day laborers of Andalusia and Extremadura: "the earnings obtained by piecework of all the members of the family, from sunrise to sunset, more than 16 hours a day [in summer], during the harvesting of the crops, the thinning of the olive trees and the harvesting of the olives; or the grape harvest, did not add up to enough to ensure even sufficient food for the whole year, when the work was only sporadic".[19]

The approval of the law of associations strengthened the workers' organizations that had been formed under the protection of the political liberalization set in motion by the first Sagasta government of 1881–1883 and which had allowed them to act within the law. This was the case of the anarcho-syndicalist Federación de Trabajadores de la Región Española (FTRE) founded in Barcelona in September 1881 and which reached almost 60,000 members grouped in 218 federations, mostly Andalusian day laborers and Catalan industrial workers. However, the FTRE was dissolved in 1888 when the sector of anarchism which criticized the existence of a public, legal organization with a syndicalist dimension and which, on the contrary, defended "spontaneism" —since any type of organization limited individual autonomy and could "distract" its components from the basic objective, the revolution, as well as favoring its "bourgeoisie"— and the "insurrectionalist" path —the uprising of the workers would put an end to capitalist society— imposed itself. Against this, the "syndicalist" tendency advocated the strengthening of organization to wrest better wages and working conditions from the bosses by means of strikes and other forms of struggle. The triumph of the "spontaneist" and "insurrectionalist" tendency was contributed to by the brutal repression unleashed by the government on the Andalusian anarchists following the murders and robberies attributed to the "Black Hand" in 1883, a mysterious and supposedly clandestine anarchist organization which had nothing to do with the FTRE. Although the anarchist movement continued to be present through publications and educational initiatives, the dissolution of the FTRE opened "the way for the predominance of individual actions of a terrorist nature, for the propaganda of the deed that it would proliferate in the following decade".[20]

For their part, the socialists, who in May 1879 had founded the Partido Socialista Obrero Español (Spanish Socialist Workers' Party) —whose objective was, as its newspaper El Socialista stated, "to procure the organization of the working class in a political party, distinct and opposed to all those of the bourgeoisie"-, called a Workers' Congress which was held in Barcelona in August 1888, from which the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT) union was born, with Antonio García Quejido as its first president. Ten days later, also in Barcelona, the I Congress of the PSOE was held, which approved what would be known as the maximum program of the party and ratified Pablo Iglesias as its president.[21]

Integrated into the Second International, the PSOE held its Labour Day on Sunday, May 4, 1890, to demand the eight-hour working day, in addition to the prohibition of work for children under 14 years of age, the reduction of the working day to 6 hours for young men and women between 14 and 18 years of age, the abolition of night work, and the prohibition of women's work in all branches of industry "which particularly affected the female organism". "The Socialist" published:[22]

Peacefully can today the workers make their strength felt... over the privileged class. Tomorrow, when the organization of the proletariat is complete, and the bourgeoisie does not want to yield to the reason that assists it and the power that accompanies it, the time will have come to proceed in a revolutionary manner.

However, unlike the anarchist organizations, the growth of the PSOE and its union UGT was very slow and it never managed to take root in Andalusia or Catalonia. In the last decade of the 19th century they had only managed to establish themselves fully among the miners of Vizcaya, thanks to the work of Facundo Perezagua, and Asturias. "Of the socialist weakness, the scarce number of votes obtained in the elections of 1891 gives an idea: little more than 1,000 in Madrid; and about 5,000 in all of Spain. Until 1910, running alone, the PSOE never obtained more than 30,000 votes in the whole country; and it did not obtain any deputy".[22]

Together with the limited process of industrialization in Spain, the slow growth of workers' organizations was due to the fact that republicanism continued to constitute a basic framework of political reference for the working and popular sectors. What basically separated republicanism from the two workerist tendencies —anarchism and socialism— was that republicans did not question the foundations of capitalist society, since they were not exclusively workers' organizations but were "interclass" parties, and therefore advocated only its reform with measures such "as the promotion of cooperativism, the constitution of mixed juries [to settle conflicts between employers and workers], the granting of cheap credit to peasants or the distribution of some lands, and, in some cases, interventionist measures by the State, such as the reduction by law of the working day or the regulation of the conditions under which it was carried out".[23]

From the Catholic world an attempt was made to create a workers' movement with this confessional significance as a result of the publication in 1891 of the papal encyclical "Rerum novarum" which encouraged initiatives in the social field. In Spain, the Círculos Católicos de Obreros, promoted by the Jesuit Antonio Vicent, arose, as well as the professional associations of mixed character, workers and employers.[24]

Spanish nationalism and the expansion of "regionalisms"

The weak process of "nation-building".

No, gentlemen, no; nations are the work of God or, if some or many of you prefer, of nature. We have all been convinced for a long time that human associations are not contracts, as was once intended; pacts of those who, freely and at every hour, can make or break the will of the parties. [...] There is no will, individual or collective, that has the right to annihilate nature or to deprive, therefore, of life the nationality itself, which is the highest, and even the most necessary, after all, of the permanent human associations. There is never right, no, neither in the many nor in the few, neither in the more nor in the less, against the homeland.

That the homeland is... for us as sacred as our own body and more, as our own family and more.... Let us preserve, then, our own, gentlemen; let us also retain our own being Spanish....

Among us, happily, the man still remains, as I have said; the Spaniard, if not yet cured of defects, retains the qualities of always; the territory can be said to be intact, with one deplorable exception... and nothing in short we lack to be able to live with honor without really trying... because what Spaniard, after all, what gathering of Spaniards can hear something that they do not know, that they do not feel, to which they do not aspire, just by feeling the sweet name of the homeland vibrate close by...

— Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, Concepto de nación, Ateneo de Madrid, November 6, 1882.

After the failure of the federal experience of the First Spanish Republic and the defeat of Carlism, during the Restoration the centralist State was consolidated, based on the iron control of the provincial and local administration by the government —including the Basque Country, whose fueros were definitively abolished in 1876—. Likewise, during this period, the process of construction of the Spanish nation continued, but from its most conservative version, as the idea of Spain did not focus on the free will of its citizens —the political nation— but on its "being", linked to its historical legacy —with Catholicism and the Castilian language as its main elements—. The leading exponents of this orquánico-historicist conception of the "Spanish nation", which opposed the liberal and republican conception of the political nation, were Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo, Juan Vázquez de Mella and the founder of the political regime of the Restoration himself, Antonio Cánovas del Castillo.[25] According to this conception, Spain was "a historical organism of basically Castilian ethno-cultural substance, which was generated over the centuries and which is, therefore, an objective and irreversible reality".[26]

However, despite the strengthening of centralism in the organization of the State, the Spanish nation-building process was less intense than in other European countries, due to the weakness of the State itself. Thus, neither the school nor the compulsory military service fulfilled the "nationalizing" function that they had, for example, in France, where the French identity eliminated "regional" and "local" identities. Thus, while in France French was imposed as the only language and the rest of the languages —contemptuously called "dialects"— ceased to be spoken or their use was considered a sign of "unculture", in Spain the languages different from Spanish —Catalan, Galician and Basque— were maintained in their respective territories, especially among the popular classes.[24]

The Spanish "nationalizing" process was also hindered by the exclusion from political participation not only of political tendencies other than the two dynastic parties, but also of the great majority of the population. Another brake, especially among the workers, was the development of socialist and anarchist organizations, which defended internationalism, not nationalism.[27] However, at least in the cities, Spanish nationalism did advance. This was demonstrated by the displays of nationalist exaltation in 1883 —as a show of support for King Alfonso XII on his return from a trip to France where he had received a hostile reception for his pro-German demonstrations—, 1885 —on the occasion of the conflict with Germany over the Caroline Islands—, in 1890 —around Isaac Peral and his invention of the submarine with electric propulsion— or in 1893 —on the occasion of the Margallo war in the vicinity of Melilla—.[24]

The expansion of "regionalisms": Catalonia, the Basque Country and Galicia

The weak process of national construction was both cause and effect of the expansion of regionalism in the eighties. From then on, opposition to the centralist State was no longer exclusive to Carlists and federalists, but was now also professed by those who felt they belonged to different homelands, especially in Catalonia, the Basque Country and Galicia, which for the time being were called regions, or at best, nationalities. But some already dared to say that Spain was not a nation but only a state made up of several nations. This was how a new phenomenon appeared, which would give rise to what would later be called the regional question, and which provoked an immediate reaction from Spanish nationalism. "A good part of the press, in Madrid and in the provinces, began to view with suspicion, if not with open hostility, even the regionalist cultural activities and their requests to co-officialize the non-Spanish languages, a claim that more than one accused of "covert separatism".[28]

Catalonia

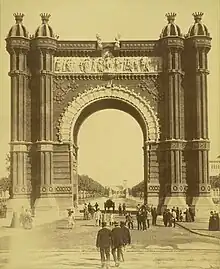

In Catalonia, after the failure of the Sexenio, a sector of federal republicanism headed by Valentí Almirall, took a Catalanist turn and broke with the bulk of the Federal Party, led by Pi i Margall. In 1879 Almirall founded the Diari Català, which although it had a short life —it closed in 1881— was the first newspaper written entirely in Catalan.[29] The following year he convened the First Catalan Congress, which in 1882 gave rise to the Centre Català, the first Catalanist organization that was clearly vindictive, although it was not conceived as a political party but as an organization for the dissemination of Catalan nationalism and to put pressure on the government. In 1885 a Memorial de greuges was presented to King Alfonso XII, denouncing the commercial treaties that were to be signed and the proposals to unify the Civil Code; in 1886 a campaign was organized against the commercial agreement that was being negotiated with Great Britain, which culminated in a rally in the Novedades theater in Barcelona that brought together more than four thousand people; and in 1888 another in defense of Catalan civil law, a campaign that achieved its goal —"the first victory of Catalanism", as one chronicler called it—.[30]

In 1886, Almirall published his fundamental work Lo catalanisme, in which he defended Catalan "particularism" and the need to recognize "the personalities of the different regions into which history, geography and the character of the inhabitants have divided the peninsula". This book constituted the first coherent and comprehensive formulation of Catalan "regionalism" and had a notable impact —decades later Almirall was considered the founder of Catalan nationalism—. According to Almirall, "the State was made up of two basic communities: the Catalan (positivist, analytical, egalitarian and democratic) and the Castilian (idealist, abstract, generalizing and dominating), so that "the only possibility of democratizing and modernizing Spain was to cede the political division of the stagnant center to the more developed periphery to form "a confederation or composite state", or a dual structure similar to that of Austria-Hungary".[29]

It was during those same 1980s when the diffusion of the symbols of Catalan nationalism began, most of which did not have to be invented, but already existed prior to its nationalization: the flag —les quatre barres de sang, 1880—, the anthem —Els Segadors, 1882—, the day of the homeland —l'11 de setembre, 1886—, the national dance —the sardana, 1892—, the two patron saints of Catalonia —Sant Jordi, 1885, and the Virgin of Montserrat, 1881—.[31]

In 1887 the Centre Català experienced a crisis as a result of the rupture between the two currents that were part of it, one more leftist and federalist led by Almirall, and the other more Catalanist and conservative, grouped around the newspaper La Renaixença, founded in 1881. The members of this second current left the Centre Catalá in November to found the Lliga de Catalunya, which was joined by the Centre Escolar Catalanista, an association of university students that included the future leaders of Catalan nationalism: Enric Prat de la Riba, Francesc Cambó and Josep Puig i Cadafalch. From that moment on, the Catalanist hegemony passed from the Centre Català to the Lliga, which during the Jocs florals of 1888 presented a second memorial de greuges to the Queen Regent in which, among other things, they asked "that the Catalan nation regain its free and independent general Courts", voluntary military service, "the official Catalan language in Catalonia", education in Catalan, a Catalan supreme court and that the king swear "in Catalonia his fundamental constitutions".[32]

Basque Country

The opposition to the definitive abolition of the Basque fueros in 1876, after the end of the Third Carlist War, was the driving force behind the development of regionalism in the Basque Country. The president of the government Cánovas del Castillo had tried to reach an agreement on the "foral arrangement" with the liberal fueros that had been pending since the approval of the law of Confirmation of the Fueros of 1839, but when he failed to do so, he ended up imposing it by means of a law that was approved by the Cortes on July 21, 1876, considered as the one which abolished the Basque fueros, but which in reality was limited to suppressing the fiscal and military exemptions which Álava, Guipuzkoa and Biscay had enjoyed until then, as they were incompatible with the principle of "constitutional unity" —the new Constitution of 1876 had just been approved—. However, Cánovas wanted to reach an agreement with the "compromising" fueristas, which would contribute to the complete pacification of the Basque Country, so he got the law to include the authorization to the government to carry out the reform of the rest of the old foral regime —with the support of the affected provinces—, This was materialized two years later in the decrees of the regime of Economic Agreements of 1878, which implied the fiscal autonomy of the Basque Country —the three Basque deputations would collect the taxes and deliver a part of them [the "quota"] to the central Treasury— which Navarre already enjoyed.[33]

The agreement reached with the "compromisers" was rejected by the "intransigent" fueristas who were not satisfied with the economic agreements. Thus arose the Euskara Association of Navarre, founded in Pamplona in 1877 and whose most prominent figure was Arturo Campión, and the Euskalerria Society of Bilbao, founded in 1880 with Fidel Sagarmínaga as president. The Navarrese Euskaros advocated the formation of a Basque-Navarre fuerist bloc over and above the division between Carlists and liberals, and adopted as their motto Dios y Fueros, the same as that of the Bilbao Euskalerriacs, who like the Euskaros also defended the Basque-Navarre union.[34]

Galicia

In Galicia between 1885 and 1890 and in parallel with what was happening in Catalonia, provincialism, which had been born in the decade of the 1940s in the ranks of progressivism and which based the particularism of Galicia on the supposed Celtic origin of its population, to which were added its own language and culture —revalued with the Rexurdimento-, was transformed into regionalism. Towards this position of defending the "general interests of Galicia" and a "Galician policy", people from different fields converged, which led to the existence of three tendencies in this incipient Galicianism: a liberal one, direct heir of progressive provincialism, and whose main ideologist was Manuel Murguía; another federalist one, of lesser weight; and a third traditionalist one headed by Alfredo Brañas. These three tendencies would converge at the beginning of the following decade in the creation of the first organization of Galicianism, the Galician Regionalist Association, which nevertheless developed little political activity during the few years it lasted (1890–1893) due mainly to the existing tension between traditionalists and liberals, especially acute in Santiago de Compostela.[35]

The "agrarian depression": free traders vs. protectionists

.jpg.webp)

In the mid-1980s the effects of the European "agrarian depression", which had begun in the middle of the previous decade and was characterized by a drop in production and falling prices due to the arrival of agricultural products from the "new countries" —Argentina, the United States, Canada, Australia— with lower production costs and whose transportation costs had been considerably reduced thanks to advances in steam navigation, were felt in Spain. The "agricultural depression" affected above all the cereal sector, concentrated in Castile, since exports were reduced, although it also affected other sectors such as sugar beet or meat —for example, Galician livestock lost its foreign markets in Great Britain—.[36]

As a consequence of the agrarian crisis, the wages of day laborers stagnated —between 1870 and 1890, the average wage was one peseta a day for ordinary work and a little more during the harvesting of crops, well below European agricultural wages— and many small landowners and tenant farmers went bankrupt, many of them opting to emigrate.[37] Thus, of the 725,000 people who emigrated between 1891 and 1900 to South America —predominantly to Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil, as well as Cuba— 65% were farmers. The annual average of emigrants in the period 1882–1889 was 62,305 and 59,072 between 1890 and 1903.[38]

The Castilian cereal owners, especially the wheat growers, formed the Agrarian League in 1887 to pressure the government to adopt protectionist measures, which had already been agreed upon by other European countries, and to reserve the domestic market for native cereals, even at the expense of consumers who would have to bear higher prices and devote a greater part of their income to the purchase of food, which in the long run would put a brake on industrialization. The protectionist campaign was joined by the Catalan textile industrialists, who were very affected by the agrarian depression because it was causing a fall in their sales. Thus, a common Castilian-Catalan front was formed, which was formalized with the celebration in Barcelona in 1888 of the National Economic Congress —in the following decade the Basque metallurgical employers would join the same—. That same year a massive demonstration and assembly was held in Valladolid, followed by others in Seville, Guadalajara, Tarragona and Borges Blanques (Lérida). And in January 1889 the Agrarian League held its II Assembly.[39]

At the head of the Agrarian League was Germán Gamazo, Minister of Overseas Territories in Sagasta's government, although his actions responded more to the interests of the faction of political friends that he headed, than to the pressure of the agrarian landowners grouped in the League.[40] This is what explains why the "gamacistas" did not support the protectionist movement until the summer of 1888 —despite the fact that it had begun much earlier— using it in the political operation of harassment of Sagasta by various liberal factions, and that they put a stop to it when in the summer of the following year they sought an agreement with Sagasta.[41]

Thus the protectionism-free trade struggle provoked tensions within Sagasta's government, because most of its members, headed by Segismundo Moret, Minister of State, were still loyal to the protectionist policy, remained faithful to the free-trade policy that the liberals had traditionally maintained —in fact it had been the first Sagasta government that in 1881 had lifted the suspension of Base Quinta of Laureano Figuerola's tariff reform approved in 1869 during the Sexenio Democrático, which established the progressive dismantling of all tariff barriers.[42][43] However, the liberals gradually revised their free trade proposals, starting with Moret himself, until they adopted a "pragmatic third way" which consisted of not increasing tariffs and at the same time not applying the tariff reductions provided for in the Fifth Base of the Figuerola tariff.[44]

The stabilization of the political regime of the Restoration (1890–1895)

The first half of the last decade of the 19th century was the period of "fullness" of the political regime of the Restoration established by Antonio Cánovas del Castillo after the Sexenio Democrático. After these five years of relative stability, during which the turn between conservatives and liberals was normalized, the regime had to face "several problems that were not on its political agenda: the workers' issue, the crystallization of a peripheral nationalism and, finally, the colonial matter itself, which led to the Cuban war of emancipation, first, and to the Spanish-American war, whose defeat marked the final crisis of the century, later on".[45]

The conservative government of Cánovas del Castillo (1890–1892)

Once his program of reforms was completed with the approval of universal (male) suffrage, Sagasta succeeded Cánovas del Castillo, who formed the government in July 1890, only a few days after the law had been voted in the Parliament. Apparently, the immediate reason for the change was the threat to Sagasta by Francisco Romero Robledo to make public certain documents on the concession of a railroad in Cuba, in which his wife was implicated —"a Cuban potentate paid more than 40,000 gold pesetas for the documents which, months later, were destroyed by Moret"—. The scandal of the Madrid Cárcel Modelo —in the hands of the liberals, as well as the city council of the capital— also had an influence when it was known, as a result of the investigations carried out on the occasion of the crime of Fuencarral Street, that the prisoners entered and left the prison freely —the conservative deputy Francisco Silvela accused the government of not managing "to make the prisons obligatory for those convicts who had the resources to have a telephone subscription"—.[46]

The new government did not modify the reforms introduced by the liberals. This was confirmed in the Regent's Message at the inauguration of the Cortes elected in 1891: "The government does not intend to present for your consideration any of the political and legal reforms which, carried out during the first days of the Regency, constitute a legal state worthy of respect".[46]

In this way, according to Suárez Cortina, "a basic feature of the Canovist system was thus sealed: liberal advances were respected by conservatism, so that the regime was consolidated on the basis of a balance between conservation and progress".[47] For this reason it was the government of Cánovas who presided over the first elections by universal suffrage held in February 1891, in which the machinery of fraud was once again at work and the conservatives obtained a large majority in the Congress of Deputies (253 seats, compared to 74 for the liberals, and 31 for the republicans).[48] Cánovas had already stated that he was not afraid of "the practical handling" of universal suffrage in spite of the fact that the number of voters increased from 800,000 to 4,800,000.[49]

The government of Cánovas del Castillo announced that, once the political and legal reforms had been completed, it was going to give preference to economic and social issues "developing a regime of effective protection for all branches of labor", with special attention to "everything concerning the interests of the working class", although on this last point no progress was made due to the opposition which the attempts to approve the first social laws met with, even within the ranks of the conservative party itself.[16] Thus, for example, the deputy Alberto Bosch y Fustegueras, of the Romero Robledo faction, spoke out against limiting the working hours of women and children with the following argument:[12]

To limit work is the most odious and the strangest of tyrannies; to limit the work of the child is to hinder technological education and learning; to limit the work of women...is even to prevent the mother from making the most beautiful of sacrifices...the sacrifice indispensable on some occasions to maintain the household of the family.

When at the end of 1890 President Cánovas del Castillo spoke at the Ateneo de Madrid of the need for State intervention to resolve the social question, alleging the insufficiency of moral attitudes —the charity of the rich and the resignation of the poor—, the traditionalist Catholic scholar Juan Manuel Ortí y Lara accused him of "falling into the abyss of socialism, violating the principles of justice, which consecrate the right to property," and then praised "the office of mendicancy, [which] is not repugnant to religion; on the contrary, religion has sanctioned it... and ennobles it. [...] The spectacle of begging... [encourages] the Christian spirit".[50]

The most important measure taken by the government was the so-called Arancel Cánovas of 1891, which repealed the free-trade Arancel Figuerola of 1869 and established strong protectionist measures for the Spanish economy, which were complemented with the approval the following year of the Ley de Relaciones Comerciales con las Antillas (Law of Commercial Relations with the Antilles). With this tariff the government satisfied the demands of certain economic sectors —Castilian cereal agriculture; Catalan textiles— in addition to joining the international trend in favor of protectionism to the detriment of free trade.[51] Cánovas explained the abandonment of free trade in a pamphlet entitled De cómo he venido yo a ser doctrinalmente proteccionista (How I came to be doctrinally protectionist) in which he justified it more for Spanish nationalist reasons than for economic reasons.[50]

The emergence of Catalan nationalism and Basque nationalism

In 1892, the year in which the Cánovas government organized the events to celebrate the IV Centenary of the Discovery of America, two events of great significance for the future took place: the approval by the recently created Unió Catalanista, the first fully political organization of Catalan nationalism, of the Bases de Manresa, the founding document of political Catalanism; and the publication of Sabino Arana's book Bizkaya por su independencia, the founding document of Basque nationalism.[51]

Catalan nationalism: the Unió Catalanista and the Bases of Manresa

In 1891 the Lliga de Catalunya proposed the formation of the Unió Catalanista, which immediately obtained the support of Catalanist organizations and newspapers, and also of individuals —unlike what had happened four years earlier with the failed Gran Consell Regional Català proposed by Bernat Torroja, president of the Associació Catalanista de Reus, which was intended to bring together the presidents of Catalanist organizations and the editors of related newspapers—. In March 1892, the Unió held its first assembly in Manresa, attended by 250 delegates representing some 160 localities, where the Bases per a la Constitució Regional Catalana were approved, better known as the Bases de Manresa, which are often considered the "founding document of political Catalanism", at least the one with conservative roots.[52]

"The Bases are an autonomist project, not at all pro-independence, of a traditional and corporatist nature. Structured in seventeen articles, they advocate the possibility of modernizing civil law, the exclusive officialdom of Catalan, the reservation for natives of public offices, including military posts, the comarca as a basic administrative entity, exclusive internal sovereignty, corporately elected courts, a higher court of last appeal, the extension of municipal powers, voluntary military service, a body of public order and its own currency, and an education sensitive to the Catalan specificity".[53]

Basque Nationalism: Sabino Arana and the foundation of the PNV

Biscay lived free and independent of foreign power, governing and legislating itself; as a nation apart, as a constituted State, and you, tired of being free, have submitted to foreign domination, you have submitted to foreign power, you have your homeland as a region of a foreign country and you have renounced your nationality to accept the foreign one.

Your usages and customs were worthy of the nobility, virtue and virility of your people, and you, degenerated and corrupted by Spanish influence, have either completely adulterated, effeminized or brutalized them. Your race... it was what constituted your Patria Bizkaya; and you, without a shred of dignity and without respect for your fathers, have mixed your blood with the Spanish or Maketa blood; you have twinned or confused yourselves with the most vile and despicable race in Europe. You possessed a language more ancient than any known... and today you shamelessly despise it and accept in its place the language of a rude and degraded people, the language of the very oppressor of your homeland.

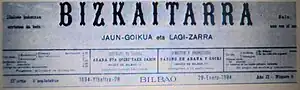

—Sabino Arara, Bizkaitarra, 1894.

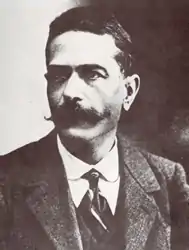

In 1892 Sabino Arana Goiri publishes the book Bizkaya por su independencia, which represents the founding document of Basque nationalism. Arana was born in 1865 in the elizate of Abando —which would end up annexed to Bilbao at the end of the 19th century— into a bourgeois, Catholic and Carlist family. On Easter Sunday 1882, when he was 17 years old, his "conversion" from Carlism to bizkaitarra nationalism took place thanks to his brother Luis Arana who convinced him —a fact that in 1932, when it was 50 years ago, the PNV celebrated as the first Aberri Eguna or Day of the Basque Homeland. "From then on Sabino devoted himself to the study of the Basque language (which he did not know, since Spanish was the language of his family), of the history and of the law (the Fueros) of Biscay, which ratified him in the revelation of his brother Luis: Biscay was not Spain".[54]

His political doctrine was specified in June of the following year in his Larrazábal speech, delivered before a group of "euskalerriacos" fueristas headed by Ramón de la Sota. In it he explained that the political objective of the book Bizcaya por su independencia was to awaken the national conscience of the Biscayans, since Spain was not their homeland but Biscay, and he adopted the slogan Jaun-Goikua eta Lagi-Zarra (JEL, 'God and Old Law'), synthesis of his nationalist program. That same year of 1893 he began to publish the newspaper Bizkaitarra in which he declared himself "anti-liberal" and "anti-Spanish" —for the latter, for which he held very radical ideas, he spent half a year in jail and the newspaper was suspended—. In 1894, Arana founded the Euskeldun Batzokija, the first batzoki, a very closed nationalist and Catholic fundamentalist center, since it only had a hundred members due to the rigid conditions of admission. It was also closed by the government, but it was the embryo of the Basque Nationalist Party (Eusko Alderdi JELtzalea, EAJ-PNV) founded clandestinely on July 31, 1895 —the feast of St. Ignatius of Loyola, whom Arana admired—. Two years later, Arana adopted the neologism Euskadi —country of the Euzkos or Basques of race—, since he did not like the traditional name of Euskalerria —people who speak Euskera—.[54]

Sabino Arana's Basque nationalist proposal was based on the following ideas:[55]

- An "organic-historicist" (or "essentialist") conception of the Basque nation —nations have always existed independently of the will of their inhabitants— whose own "being" are the Catholic religion and the Basque race —identified by surnames and not by place of birth, hence the requirement to have the first four Basque surnames to be a member of the first batzoki, although the PNV later reduced them to one— and not the Basque language —in which it differed notably from Catalan nationalism, whose most important identity trait was the language. "If we were given a choice between a Biscay populated by Maketos who only spoke Basque and a Biscay populated by Biscayans who only spoke Castilian, we would choose without hesitation the latter because the Biscayan substance with exotic accidents that can be eliminated and replaced by natural ones is preferable to an exotic substance with Biscayan properties that could never change it," wrote Sabina Arana in her 1894 opuscule Errores Catalanistas.

- Catholic integralism and providentialism that leads him to reject liberalism, since it "takes us away from our ultimate end, which is God", and consequently to demand independence from liberal Spain, and thus achieve the religious salvation of the Basque people. "Bizkaya, dependent on Spain, cannot turn to God, cannot be Catholic in practice", he affirmed, and therefore proclaimed that his call for independence "ONLY BY GOD HAS IT RESOUNDED".

- The Basque nation understood as antagonistic to the Spanish nation —they are different "races"— since they have been enemies since ancient times. Biscay, like Gipuzkoa, Alava and Navarre, always fought for their independence from Spain, which they achieved when the "Spanish" kings had no choice but to grant them their privileges. Since then, according to Arana, the four territories were independent from Spain and from each other, until in 1839 the fueros were subordinated to the Spanish Constitution, because according to Arana, unlike the fueros supporters, Basque fueros and Spanish Constitution were incompatible. "The year 39 Biscay fell definitively under the power of Spain. Our homeland Bizkaya, from the independent nation it was, with its own power and rights, became on that date a Spanish province, a part of the most degraded and abject nation in Europe," wrote Arana in 1894.

- The Basque people —defined racially, not linguistically or culturally— has been "degenerated" in a long process that culminated in the 19th century with the disappearance of the Fueros. In this process the Spanish immigrants who have arrived —"invaded", according to Arana— the Basque Country to work in its mines and factories —the maquetos— are to blame for all the evils: for the disappearance of the traditional society —with industrialization, hence Arana's initial anti-capitalism and idealization of the rural world: "Let Biscay be poor and have nothing but fields and cattle, and we would then be patriotic and happy"— and of its culture based on the Catholic religion —with the arrival of modern anti-religious ideas, such as "impiety, every kind of immorality, blasphemy, crime, free thought, unbelief, socialism, anarchism. ..."— and the decline of the Basque language.

- The only way to put an end to the "degeneration" of the Basque race is to recover its independence from Spain, returning to the situation prior to 1839 —the fundamental thing, according to Arana, was to demand the repeal of the law of 1839, not that of 1876—. Once independence was achieved, a Confederation of Basque States would be formed with the former foral territories on both sides of the Pyrenees —Biscay, Gipuzkoa, Alava and Navarre, on the southern side; Benabarra, Labourd and Zuberoa, on the northern side—. This Confederation, which he called Euskadi, would be based on the "unity of race, as far as possible" and on "Catholic unity", so that it would only include Basques of race and confessional Catholics, excluding not only Macheto immigrants but also Basques of liberal, republican or socialist ideology.

The fall of the conservatives and the return of the liberals (1893–1895): anarchist terrorism

In the conservative government of Cánovas two opposing tendencies of conservatism coexisted, represented by Francisco Romero Robledo —who had returned to the ranks of the Conservative Party after his failed experience with the Liberal-Reformist Party— and Francisco Silvela. The former embodied "the dominance of clientelistic practices, electoral manipulation and the triumph of the crudest pragmatism", while the latter represented "conservative reformism", which sought to "reestablish the prestige of the law and cut off all abuse, all infringement". President Cánovas del Castillo leaned towards Romero Robledo's "pragmatism" in the face of the new situation created by the introduction of universal suffrage, so Silvela left the government in November 1891[48] and his departure provoked the greatest internal crisis in the history of the Conservative Party.

In December 1892, a case of corruption in the Madrid City Council provoked a crisis in the government of Cánovas, which the regent solved by calling Sagasta again —in the debate that took place in the Congress the rupture between Cánovas and Silvela was consummated when the latter mentioned the obligation of "putting up with the boss", which motivated the angry response of the former—.[56] Sagasta, following the customs of the Canovist system, obtained the decree for the dissolution of the Parliament and the calling of new elections to obtain a broad majority to support the new government. The elections were held in March 1893 and, as was to be expected, they were a resounding triumph for the government candidates (the liberals obtained 281 deputies, against 61 for the conservatives —divided between canovistas, 44, and silvelistas, 17— plus 7 Carlists, 14 republican posibilistas and 33 republican unionists.[57]

Sagasta formed a government called of notables because it included all the faction leaders of the liberal party, including General López Domínguez who rejoined their ranks, and the republican possibilists of Emilio Castelar —whom Cánovas forced to publicly abjure his republican faith, by the voice of Melchor Almagro—, and had to make an effort to reconcile the "right-wing" and "protectionist" positions of Germán Gamazo with the "left-wing" and "free trade" positions of Segismundo Moret. Gamazo, at the head of the Treasury portfolio, proposed to achieve a balanced budget, but his project was frustrated by the increase in spending caused by the brief Margallo war that took place around Melilla between October 1893 and April 1894. The reason for the war was the conflict arising from the construction of a fort in an area near Sidi Guariach where there was a mosque and a cemetery, which was considered by the Rifians as a desecration. Hard fights took place, in which the siege of the fort of Cabrerizas Altas stood out, surrounded by around 1000 men and resulting in 41 dead and 121 wounded among the Spanish forces.[58]

For his part, the Minister of Overseas Antonio Maura, son-in-law of Gamazo, started the reform of the colonial and municipal regime of the Philippines to provide them with a greater administrative autonomy —in spite of the opposition it aroused among certain sectors of Spanish nationalism and the Church—, but he failed in his attempt to do the same in Cuba, because the reform seemed too advanced to the Spanish Constitutional Union, while it did not satisfy the aspirations of the Cuban Autonomist Liberal Party. The project was rejected by the Parliament, where it was branded as unpatriotic, and Minister Maura was even described as a filibuster, a fool and an madman. Maura and his father-in-law Germán Gamazo resigned, opening a serious crisis in Sagasta's government.[59]

A serious problem the government had to face was that of the anarchist terrorism of "propaganda by the deed" justified by its supporters as a response to the violence of bourgeois society and the bourgeois state, which made the lives of many workers desperate, as well as a form of replesalia against the brutal repression of the police. Its main scenario was the city of Barcelona. The first important attack had taken place in February 1892 in the Plaça Reial in Barcelona, resulting in the death of a rag-picker and the wounding of several people. The first with a markedly political objective took place on September 24, 1893, and was directed against General Arsenio Martínez Campos, Captain General of Catalonia and one of the key figures of the Restoration. Martínez Campos was only slightly wounded, but one person died and others were injured in different ways. The author of the attack, the young anarchist Paulino Pallás —who was shot two weeks later— justified it as a reprisal for the incidents that had occurred a year and a half earlier in Jerez de la Frontera when, on the night of January 8, 1892, some 500 peasants tried to take the city to free some fellow prisoners in jail and two neighbors and one of the assailants died, The indiscriminate repression of the Andalusian workers' organizations began – four workers were executed because of a court martial, and sixteen more were condemned to life imprisonment; all of them had denounced that their confessions had been obtained through torture. The revenge announced by Paulino Pallás shortly before being shot was fulfilled three weeks later, when on November 7 the anarchist Santiago Salvador threw two bombs into the stalls of the Liceu Theater in Barcelona, although only one exploded, killing 22 people and wounding 35 others.[60]

Finally the government fell in March 1895 because Sagasta resigned when he refused to accept General Martínez Campos' demand that the journalists of two newspapers whose editorial offices had been assaulted by a group of officers unhappy with the news they had published, which they considered injurious, be tried by military tribunals. Cánovas returned to the presidency of the government. A month before, the war in Cuba had begun.[61]

The Margallo war (1893–1894)

.jpg.webp)

In 1893 Muslims in Melilla opposed the construction of the Fort of the Immaculate Conception at Sidi Guariach, and staged an attack on October 3. The 1,463 soldiers of the Melilla garrison had to face between 8,000 and 10,000 Muslims.[62] Minister José López Domínguez sent as reinforcements, under the command of General Ortega, a total of 350 soldiers.[63] In the counterattack of October 28 the governor Juan García Margallo died in the door of the fort of Cabrerizas Altas. A fleet was sent to support the Spanish troops with naval bombardments. Subsequently, an expeditionary army was created in the peninsula under the command of Captain General Arsenio Martinez Campos, 20,000 men.[63] These troops arrived in Melilla on November 29, producing a deterrent effect, and the fighting ceased.[62] After this, Spain completed the construction of the fort.[63] On March 5, 1894, Martínez Campos signed the Treaty of Fez with the Sultan, in which he undertook to guarantee peace in the region and compensated Spain with 20 million pesetas.[63]

The crisis at the end of the century (1895–1902)

The crisis at the end of the century was provoked by the Cuban War of Independence, which began in February 1895 and ended with the Spanish defeat in the Spanish-American War of 1898.[64] But at the internal level anarchist terrorism also played an important role, whose attack of greater repercussion took place in Barcelona on June 7, 1896, during the passage of the Corpus Christi procession through Canvis Nous street in which six people died on the spot, and forty-two others were wounded. The police repression that followed was brutal and indiscriminate and gave rise to the famous Montjuic trial, during which 400 "suspects" were imprisoned in the castle of Montjuic, where they were brutally tortured — "nails pulled out, feet crushed by presses, electric helmets, cigars extinguished on the skin..."—.[65] Afterwards, several courts-martial sentenced 28 people to death—five of whom were executed— and 59 others to life imprisonment —63 were declared innocent but were deported to Rio de Oro—.[66] The Montjuic trial had great international repercussions, given the doubts about the evidence on which the convictions had been based —basically the confessions of the defendants obtained under torture—, which was also followed by a campaign by the Spanish press against the government and the "executioners", in which the young journalist Alejandro Lerroux, director of the Madrid Republican newspaper El País, stood out. Under the title Las infamias de Montjuïc (The infamies of Montjuïc), he published for months the accounts of the tortured —in addition, Lerroux undertook a propaganda tour of La Mancha and Andalusia—. In this exalted atmosphere of protests against the Montjuic trials, the assassination of the president of the government Antonio Cánovas del Castillo by the Italian anarchist Michele Angiolillo took place on August 8, 1897. Práxedes Mateo Sagasta had to take charge of the government.[67]

The Cuban War (1895–1898)

The Spanish policy with respect to Cuba after the signature of the "peace of Zanjón" of 1878, that put an end to the Ten Years' War, was its assimilation to the metropolis, as if it was one more Spanish province —it was granted, as Puerto Rico, the right to elect deputies to the Congress in Madrid—. This policy of Spanishization, which was intended to counteract Cuban secessionist nationalism, was reinforced by the facilities granted for the emigration of peninsulars to the island, which was especially taken advantage of by Galicians and Asturians —between 1868 and 1894 nearly half a million people arrived, for a total population of 1,500,000 in 1868—. But the Restoration governments never approved the granting of any kind of political autonomy for the island, as they considered that this would be the previous step to independence. A former liberal minister of Overseas Territories put it this way: "by many roads one can go to separation, but by the road of autonomy the teachings of history tell me that it is by railroad".[68] Cuba was considered "part of the nation's territory, which politicians should preserve in its integrity".[69]

In this way, they refused to accept the proposals of the Cuban Liberal Autonomist Party which, as opposed to the Spanish Constitutional Union, absolutely opposed to any concession, wanted to "obtain by peaceful and legal means some particular political institutions for the island, where they could participate". What they did achieve was the definitive abolition of slavery in 1886.[70] Meanwhile, Cuban nationalism for independence continued to grow, fed by the memory of the heroes of the war and the Spanish brutalities of the war.[71]

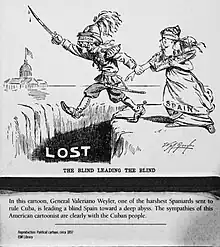

In the last Sunday of February 1895, the day the carnival began, a new pro-independence insurrection broke out in Cuba, planned and directed by the Cuban Revolutionary Party, founded by José Martí in New York in 1892, who would die the following month in a confrontation with Spanish troops. The Spanish government reacted by sending to the island an important military contingent —some 220,000 soldiers would arrive in Cuba in three years—.[72] In January 1896, General Valeriano Weyler relieved General Arsenio Martínez Campos —who had failed to put an end to the insurrection— of his command, determined to carry the war "to the last man and the last peseta".[73] "With the new Captain General, the Spanish strategy changed radically. Weyler decided that it was necessary to cut off the support that the independence fighters received from the Cuban society; and for that reason he ordered that the rural population be concentrated in towns controlled by the Spanish forces; at the same time he ordered the destruction of the crops and cattle that could serve as supply for the enemy. These measures gave good results from the military point of view, but with a very high human cost. The reconcentrated population, without sanitary conditions or adequate food, began to fall victim to diseases and to die in great numbers. On the other hand, many peasants, with nothing left to lose, joined the insurgent army". The brutal measures applied by Weyler caused a great impact on international public opinion, especially in the United States.[74]

Meanwhile, in 1896 another independence insurrection began in the Philippine archipelago led by the Katipunan, a Filipino nationalist organization founded in 1892. Unlike in Cuba, the rebellion was stopped in 1897, although General Polavieja resorted to methods similar to those of Weyler —José Rizal, the main Filipino nationalist intellectual, was executed—.[75] In mid 1897 General Polavieja was relieved of his command by General Fernando Primo de Rivera who reached a pact with the rebels at the end of the year.[76]

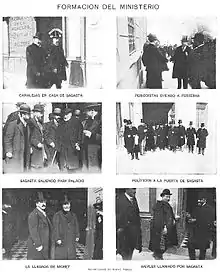

On August 8, 1897, Cánovas was assassinated, and Sagasta, the leader of the Liberal Party, had to take over the government in October, after a brief cabinet presided over by General Marcelo Azcárraga Palmero. One of the first decisions he took was to dismiss General Weyler, whose policy of harshness was not giving results, and he was replaced by General Ramón Blanco y Erenas. Likewise, in a last attempt to reduce support for the insurrection, political autonomy was granted to Cuba —also to Puerto Rico, which remained at peace—, but it came too late and the war continued.[77] On the other hand, Spanish policy in Cuba concentrated on satisfying the demands of the United States, with the objective of avoiding war at all costs, since the Spanish rulers were aware of Spain's naval and military inferiority, although the press, on the other hand, deployed an anti-American campaign of Spanish exaltation.[78]

The Spanish-American War

Besides the geopolitical and strategic reasons, the North American interest for Cuba —and for Puerto Rico— was due to the increasing interdependence of their respective economies —investments of North American capital; 80% of the Cuban sugar exports were already going to the United States— and also to the sympathy that the Cuban independence cause awoke among the public opinion especially after the sensationalist press aired the brutal repression exercised by Weyler and initiated an anti-Spanish campaign asking for the intervention of the North American army on the side of the insurrectionists. In fact, the American aid in arms and supplies channeled through the Cuban Junta presided by Tomás Estrada Palma and the Cuban League "was decisive to prevent the subjugation of the Cuban guerrillas", according to Suárez Cortina. The American position was radicalized with the Republican President William McKinley, elected in November 1896, who discarded the autonomist solution admitted by his predecessor, the Democrat Grover Cleveland, and clearly bet for the independence of Cuba or the annexation —the American ambassador in Madrid made an offer of purchase of the island that was rejected by the Spanish government—. Thus, the granting of autonomy to Cuba approved by the government of Sagasta —the first experience of this type in contemporary Spanish history— did not satisfy at all the American pretensions, nor those of the Cuban independence fighters who continued the war.[79] Relations between the U.S. and Spain worsened when the American press published a private letter from Spanish Ambassador Enrique Dupuy de Lome to Minister José Canalejas, intercepted by Cuban espionage, in which he called President McKinley "weak and populist, and also a politician who wants... to look good with the jingoes of his party".[80]

In February 1898, the American battleship Maine sank in the port of Havana where it was anchored as a result of an explosion – 264 sailors and two officers died— and two months later, on April 19, the United States Congress passed a resolution demanding the independence of Cuba and authorizing President McKinley to declare war on Spain, which he did on April 25.[81] The congressional resolution stated "that the people of the island of Cuba are, and have the right to be, free, and that it is the duty of the United States to request, and therefore the government of the United States requests, that the Spanish government immediately relinquish its authority and rule over the island of Cuba and withdraw from Cuba and Cuban waters its land and naval forces".[82] The causes of the explosion of the Maine are still unknown, although "current studies are inclined to attribute it to an accident, which confirms the thesis put forward by the Spanish commission that the explosion was due to internal causes. The official American report attributed it, on the contrary, to external causes, and it was, in the words of McKinley's Message to Congress, "a patent and manifest proof of an intolerable state of affairs in Cuba".[83]

The Spanish-American war was brief and was decided at sea. On May 1, 1898, the Spanish squadron in the Philippines was sunk off the coast of Cavite by an American fleet —and the disembarked American troops occupied Manila three and a half months later— and on July 3 the same thing happened to the fleet sent to Cuba under the command of Admiral Cervera off the coast of Santiago de Cuba —few days later Santiago de Cuba, the second most important city on the island, fell into the hands of the American troops that had disembarked—. Shortly afterwards, the Americans occupied the neighboring island of Puerto Rico.[84] There were Spanish officers in Cuba who expressed "the conviction that the Madrid government had the deliberate purpose of having the squadron destroyed as soon as possible, in order to achieve peace quickly".[85]

To make matters worse, some of the best units of the navy such as the battleship Pelayo or the cruiser Carlos V did not intervene in the war[86] despite being superior to their American counterparts, increasing the feeling among some that they were witnessing a "controlled demolition" by the Spanish government of ungovernable colonies that were to be lost sooner rather than later to prevent the restoration regime from collapsing (in fact, the few possessions that Spain retained after this war were sold in 1899 to Germany). Finally, the Spanish government asked in July to negotiate peace.

After learning of the sinking of the two fleets, the government of Sagasta requested the mediation of France to initiate peace negotiations with the United States, which after the signing of the protocol of Washington on August 12, began on October 1, 1898, and culminated with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on December 10.[85] By this Treaty, Spain recognized the independence of Cuba and ceded to the United States Puerto Rico, the Philippines and the island of Guam, in the Mariana Archipelago. The following year Spain sold to Germany for 25 million dollars the last remnants of its colonial empire in the Pacific, the Caroline Islands, the Marianas —minus Guam— and Palau. "Described as absurd and useless by much of historiography, the war against the U.S. was sustained by an internal logic, in the idea that it was not possible to maintain the monarchic regime if it was not based on a more than foreseeable military defeat," says Suarez Cortina.[87] A point of view shared by Carlos Dardé: "Once the war had started, the Spanish government believed it had no other solution than to fight and lose. They thought that defeat —certain—was preferable to revolution —also certain—". To grant "independence to Cuba, without being defeated militarily... would have implied in Spain, more than probably, a military coup d'état with broad popular support, and the fall of the monarchy; that is to say, revolution".[88] As the head of the Spanish delegation to the Paris peace negotiations, the liberal Eugenio Montero Ríos, said: "Everything has been lost, except the Monarchy". Or as the American ambassador in Madrid said: the politicians of the dynastic parties preferred "the probabilities of a war, with the certainty of losing Cuba, to the dethronement of the monarchy".[89]

The "disaster of '98" and "regenerationism".

After the defeat, the Spanish nationalist patriotic exaltation gave way to a feeling of frustration, increased when the total number of dead during the war was known: about 56,000 —2,150 soldiers and officers killed in combat, and 53,500, due to various diseases—. The historian Melchor Fernandez Almagro, who was a child when the war ended, referred to the wounded and mutilated soldiers returning from the colonial campaign "walking the streets and squares in painful and inevitable display of the uniform of rayadillo reduced to rags, with gloomy profusion of crutches, arms in sling and patches on the emaciated face".[90]

However, this sentiment had no political translation since both Carlists and Republicans —with the exception of Pi i Margall who maintained an anti-colonialist stance— had supported the war and had manifested themselves as nationalist, militarist and colonialist as the parties of the turn—only socialists and anarchists remained faithful to their internationalist, anti-colonialist and anti-war ideology— and the Restoration regime would manage to overcome the crisis.[91][92]

In the years immediately after the war, regenerationism gained strength, a current of opinion that proposed the need to "vivify" —to regenerate— Spanish society so that the "disaster of '98" would not be repeated. This current participated fully in what was called the literature of Disaster, which had already begun some years before 98 —Lucas Mallada had published Los males de la Patria in 1890— and which set out to reflect on the causes which had led to the situation of "prostration" in which the Spanish Nation found itself —as demonstrated by the fact that Spain had lost its colonies while the rest of the main European States were building their own colonial empires— and on what had to be done to overcome it. Among the many works published were Ricardo Macías Picavea's El problema nacional (1899), Damián Isern's Del desastre nacional y sus causas (1900) and Doctor Madrazo's ¿El pueblo español ha muerto? (1903). Also participating in this debate on the "problem of Spain" were the writers of what years later would be called, precisely, the Generation of '98: Ángel Ganivet, Azorín, Miguel de Unamuno, Pío Baroja, Antonio Machado, Ramiro de Maeztu, etc.[93][94]

But, undoubtedly, the most influential author of the regenerationist literature was Joaquín Costa. In 1901 he published Oligarquía y caciquismo, in which he pointed to the political system of the Restoration as the main cause of Spain's "backwardness". To "regenerate" the "sick organism" that was Spain in 1900, an "iron surgeon" was needed to put an end to the "oligarchic and cacique" system and promote a change based on "school and pantry".[93]

To contain the movement of regression and Africanization, absolute and relative, which is dragging us further and further out of the orbit in which European civilization revolves and develops, to carry out a re-foundation of the Spanish State. On the European pattern that history has given us and to whose thrust we have succumbed, to reestablish the credit of our nation before the world, to prevent Santiago de Cuba from finding a second edition by Santiago de Galicia? or in other words: to found a new Spain in the Peninsula, that is to say, a rich Spain that eats, a cultured Spain that thinks, a free Spain that governs, a strong Spain that wins, a Spain, in short, a Spain that is contemporary with humanity, that on crossing the borders does not feel foreign, as if it had entered another planet or another century (...) and let us not spend our time in the middle of a new Spain, as if it had entered another planet or another century (...) and let us not spend our time in the middle of a new Spain. ...) and that we do not pass in a short time from an inferior class to an inferior race, that is, from vassals that we have been of an indigenous oligarchy, to colonists that we have begun to be of the French, English and Germans.

Joaquín Costa, Oligarquía y caciquismo, 1901.

The "regenerationist" governments (1898–1902)

In March 1899 the new conservative leader, Francisco Silvela, took charge of the government, which was a great relief for Sagasta, who had been at the head of the State during the days of the disaster of '98.[95] Silvela echoed the demands for the "regeneration" of society and the political system —he himself characterized the situation as that of a country "without pulse"—, which was translated into a series of reformist measures. Silvela's project —and that of General Polavieja, Minister of War— consisted of "a conservative regeneration formula that tried to safeguard patriotic values at a time of national crisis".[96]