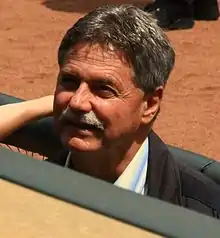

| Reid Nichols | |

|---|---|

| Outfielder | |

| Born: August 5, 1958 Ocala, Florida, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| September 16, 1980, for the Boston Red Sox | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| October 4, 1987, for the Montreal Expos | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .266 |

| Home runs | 22 |

| Runs batted in | 131 |

| Teams | |

Thomas Reid Nichols (born August 5, 1958) is an American former outfielder and coach in Major League Baseball (MLB). He played for the Boston Red Sox (1980–1985), Chicago White Sox (1985–1986), and Montreal Expos (1987). Listed at 6 feet 0 inches (1.83 m) and 195 pounds (88 kg), he batted and threw right-handed. After his playing career ended, he served as a coach and minor league coordinator for the Baltimore Orioles, Texas Rangers, and Milwaukee Brewers.

Though he did not watch professional baseball growing up, Nichols started playing Little League Baseball at age 11 and drew interest from the Red Sox and the Los Angeles Dodgers when he graduated high school. The Red Sox selected him in the 12th round (286th overall) of the 1976 MLB draft, and he debuted with them in 1980. Though never an everyday starter, he batted a career-high .302 in 1982 and played a career-high 100 games in 1983. In 1985, he was traded to the White Sox, remaining with them through the 1986 season. Nichols played for the Expos in 1987, spent part of 1988 in the Texas Rangers organization, and joined the Chicago Cubs for 1989 spring training before retiring.

After a brief stint captaining fishing tours, Nichols became a coach for the Orioles, working alongside Doug Melvin in Baltimore. When Melvin became the general manager of the Rangers and later the Brewers, he brought Nichols with him to those organizations. Nichols instituted a program to teach Ranger prospects financial literacy and etiquette, and with the Brewers, he helped the team develop such prospects as Ryan Braun, Prince Fielder, and Rickie Weeks.

Early life

Thomas Reid Nichols was born on August 5, 1958, in Ocala, Florida, to parents Leon and Judy. Leon supported the family by servicing outboard motors. Reid did not watch professional baseball growing up, but at the age of 11, he tried out and made a local Little League Baseball team which played at Grant Field, later the spring training home of the Toronto Blue Jays. Nichols made the league's All-Star team. At Forest High School, he starred on the school's baseball team and was teammates with Scot Brantley, who would later reach the National Football League (NFL) as a linebacker. Nichols's coach, Mike McGrath, arranged for Nichols and Brantley to try out for the Los Angeles Dodgers. McGrath also informed George Digby, a scout for the Boston Red Sox, that Nichols was an exciting prospect.[1][2]

Under Digby's recommendation, the Red Sox selected Nichols in the 12th round (286th overall) of the 1976 Major League Baseball (MLB) draft. Though he had committed to play college baseball for the Auburn Tigers, he decided to take the opportunity to play professionally. Since he was only 17, his father signed his Red Sox contract for him.[2]

Minor league career

Nichols began his professional career in 1976 with the Elmira Pioneers of the New York–Penn League, which despite being a rookie-level team boasted several future major leaguers.[2] In 23 games (53 at bats), he batted .340 with eight runs scored, 18 hits, no home runs, nine runs batted in (RBI), and two stolen bases.[3] With a 50–20 record, Elmira won the league pennant.[2]

In 1977 and 1978, Nichols played for the Single-A Winter Haven Red Sox of the Florida State League. He batted .264 with 41 runs scored, 102 hits, two home runs, 34 RBI, and 13 stolen bases in 116 games (387 at bats) the first year. In 1978, he batted .247 with 52 runs scored, 102 hits, five home runs, 34 RBI, and 15 stolen bases.[3] Nichols considered Winter Haven a difficult experience: many of his competitors had played college baseball, while he was only 18 years old.[2]

With the Single-A Winston-Salem Red Sox of the Carolina League in 1979, Nichols had his finest season yet. He recorded a 30-game hitting streak, one short of the league record set in 1948.[2] Playing 134 games, he ranked among the Carolina League leaders with a .293 batting average (fifth), 25 doubles (tied with Michael Barnes and Jeffrey Gossett for third behind Greg Walker's 27 and Michael Barnes's 26), and 12 home runs (tied with Craig Brooks for fourth, behind Gary Pellant's 18 and Gossett's and Mike Fitzgerald's 13). He stole 66 bases, second only to Bob Dernier's 77. Nichols led the league with 107 runs scored and 156 hits.[4] He finished second to Dernier in Carolina League Most Valuable Player (MVP) voting.[2]

Because of his strong performance with Winston-Salem, Nichols was invited to spring training with Boston in 1980. He batted .400 in the preseason but was assigned to the Triple-A Pawtucket Red Sox of the International League, where he would spend most of the season. It was not always an easy year. "I was batting .188 and I wasn’t having any fun,” he recalled. “I went out and bought some cowboy boots and cowboy hat and I showed up to the stadium wearing it and decided it was time to have fun playing baseball again, and after that I improved."[2] In 134 games for Pawtucket, he batted .276 with four home runs and 42 RBI.[3] He ranked among the International League leaders with 68 runs scored (tied with Greg Johnston for seventh), 141 hits (eighth), and 23 stolen bases (seventh).[5]

Major league career

Boston Red Sox (1980–1985)

When Pawtucket's 1980 season came to an end, Nichols was a September callup by Boston. He made his major league debut on playing center field on September 16, singling against Ross Grimsley in the fourth inning for his first major league hit as the Red Sox beat the Cleveland Indians 9–5.[2][6] After collecting just one hit in his next seven games, he had three on October 1 in a 12–8 loss to the Baltimore Orioles.[7] He batted .222 with five runs scored, eight hits, no home runs, three RBI, and no stolen bases in 12 games (36 at bats).[1]

In 1981, Nichols battled veteran Rick Miller in spring training for the starting spot in center field. He hit a home run against the New York Yankees late in the spring season, but Miller won the job, and Nichols spent the year as a reserve outfielder on Boston's roster.[8][9] The season was interrupted for two months from June through August due to the 1981 MLB strike.[10] In 39 games (48 at bats), Nichols batted .188 with 13 runs scored, nine hits, no home runs, three RBI, and 0 stolen bases.[1]

Local sportswriters speculated in 1982 spring training about how much Nichols would be used during the season. "The only goal I set is to be the best player I can be," Nichols said. "I want to play every day at 120 percent. I’d like to have some more playing time because experience is the best teacher. I can be a better player just by playing."[11] Nichols did receive more playing time in 1982, getting many starts in left field as well as center field.[12] He hit his first regular season major league home run on May 28, a solo shot against Floyd Bannister in a 3–2 victory over the Seattle Mariners.[2] In July, manager Ralph Houk praised Nichols: "[E]very time he’s played, he’s done well. … And when he’s on the bench he’s an asset with his speed if I need a pinch runner."[13] On August 23, his eighth-inning, two-run home run against Bill Caudill turned a 3–2 deficit into a 4–3 lead, which would be the final score in Boston's victory over Seattle.[14] Facing the Mariners again the next day, he hit two home runs: the first coming against Bob Stoddard in the fourth inning, and the second a game-winner coming against Caudill in the 10th inning as the Red Sox won 5–4.[15] Ultimately, Nichols played 92 games for the Red Sox, setting career highs in batting average (.302), runs scored (35), home runs (7), and RBI (33). He had 74 hits and five stolen bases.[1]

Over the 1982–83 offseason, Nichols played winter ball in the Dominican Republic. He hoped to be the starting center fielder in 1983 but was disappointed that December when he learned that the Red Sox had acquired Tony Armas.[16] In an interview with the Waterbury Republican, he stated: "I’m content with whatever I get to do. I’m going to do whatever I can to help this club, and I’m not going to complain about anything ... We’ve got a good outfield, but you never know what could happen, and I’ll be ready to go in there when I’m needed, just like last year."[17] As it turned out, he would make several starts in center field, usually when Armas was serving as the designated hitter, and he played several games in right field as well.[18][19] On May 9, he had four hits, scored twice, and hit a two-run home run against Dave Goltz in an 8–2 victory over the California Angels.[20] He had three hits on May 25, and his ninth-inning single with the bases loaded against Dennis Lamp scored the only runs of the game in a 2–0 victory over the Chicago White Sox.[21] In 1983, Nichols appeared in a career-high 100 games, recording 78 hits, 6 home runs, and 22 RBI. He set or tied career highs with 78 hits, 35 runs scored, and 7 stolen bases.[1] After the season, the Red Sox rewarded his performance with a five-year contract.[2]

Nichols did not have the same level of success in 1984, and after starting in left field and center field several times in April and May, he was used as a pinch hitter for much of the rest of the year.[2][22] He was almost traded to the Yankees for Shane Rawley that month.[23][24] On June 11, he pinch-hit for Rich Gedman in the bottom of the ninth inning against the Yankees after the Red Sox had scored three runs to tie the game at six. With two outs and a 2–2 pitch count, Nichols fouled off four pitches in a row, then hit a fastball from Bob Shirley into the stands for a game-ending, three-run home run, helping the Red Sox defeat their rivals.[23] In 74 games, he batted .226 with 14 runs scored, 28 hits, 1 home run, 14 RBI, and 2 stolen bases.[1]

Sparingly used by the Red Sox in 1985, Nichols played a number of positions, including every outfield position and three games at second base.[25] In the bottom of the 10th inning on May 10, with runners on first and second and the game against the Oakland Athletics tied at four, Nichols singled against Jay Howell to score Bill Buckner and give Boston a 5–4 win.[26] Facing Oakland on July 10, he hit a home run against Bill Krueger in a 5–4 loss.[27] The next day, he was traded by Boston to the White Sox in exchange for Tim Lollar.[1] This made him one of the only Red Sox players to hit a home run in his final at bat with the team; one of the others was Ted Williams.[2] In 21 games with Boston, he had batted .188 with three runs scored, six hits, one home run, three RBI, and one stolen base.[1]

Chicago White Sox (1985–1986)

With Chicago, Nichols received more playing time, appearing in 51 games in the latter part of the season.[1] On July 18, he had four hits and three RBI as the White Sox defeated Cleveland 10–0.[28] Against the Yankees on August 4, his catch of a Don Baylor fly ball was the final out of Tom Seaver's 300th career win.[29] With Chicago, he batted .297 with 20 runs scored, 35 hits, one home run, 15 RBI, and five stolen bases. In 72 games combined between Boston and Chicago, he batted .273 with 23 runs scored, 41 hits, 2 home runs, 18 RBI, and 6 stolen bases.[1]

Nichols saw time at all the outfield positions in 1986, also playing second base twice.[30] Facing his former team on April 12, he had two hits and three RBI in a 3–1 victory.[31] On May 16, his three-RBI double against Charlie Leibrandt put the White Sox up for good in a 4–2 victory over the Kansas City Royals.[32] In the first game of a doubleheader opening a series against the Mariners on September 30, Nichols pinch-hit for Daryl Boston and had a game-tying RBI single against Matt Young. He then had a walkoff single with the bases loaded in the 10th inning against Ed Nunez, giving Chicago a 5–4 victory.[33] After not hitting a home run all season, Nichols hit one in each of the final games of the Seattle series.[30] His second, on October 1, was part of three hits and three RBI he had as the White Sox defeated the Mariners, 3–1.[34] In 74 games, he batted .228 with 9 runs scored, 31 hits, 2 home runs, 18 RBI, and 5 stolen bases.[1]

Montreal Expos (1987)

Nichols spent spring training in 1987 competing for a spot on the White Sox' roster but was released on March 30.[1][2] Four days later, he was signed by the Montreal Expos, who were in need of another outfielder after failing to come to terms with Tim Raines.[1][2] Even after Raines finally signed with the ballclub on May 1, the team kept Nichols around for the rest of the year.[35][36] Nichols enjoyed playing for the team. "[T]here wasn’t as much pressure there. We had a good team that year and after the games, there would be 12 guys going out to dinner together," he reminisced.[2] On May 9, his three-run home run against Jim Deshaies provided all of Montreal's scoring in a 3–1 victory over the Houston Astros.[37] His last appearance for the Expos was in the team's final game of the year, on October 4, when he played center field in a 7–5 loss to the Chicago Cubs.[35] In 77 games, he batted .265 with 22 runs scored, 39 hits, 4 home runs, 20 RBI, and 2 stolen bases.[1] The Expos granted him free agency on November 9.[1]

Texas Rangers organization (1988)

Nichols was at spring training for Houston in 1988, but he did not make the team.[1][38] Returning to his home of Sarasota, Florida, he fished and played slow-pitch softball while hoping that another MLB team would sign him. On July 21, he was finally picked up by the Oklahoma City 89ers, the Triple-A affiliate of the Texas Rangers. "I could hardly expect anything else after sitting at home all summer," he said.[39] The 89ers had struggled to field a full roster following several callups by the Rangers, as well as the retirements of Steve Kemp and Ruppert Jones and an injury to Tito Landrum.[40] In 38 games, Nichols batted .241 with 19 runs scored, 32 hits, two home runs, and 19 RBI in 133 at bats in what would be his last professional season.[3] He signed with the Chicago Cubs for 1989 but retired towards the end of spring training.[41]

Career statistics

In an eight-year career, Nichols batted .266 (308 hits in 1160 at bats) with 156 runs scored, 63 doubles, 8 triples, 22 home runs, 131 RBI, 27 stolen bases, and a .326 on-base percentage in 540 games. He posted a .990 fielding percentage in 408 outfield appearances, committing eight errors in 782 chances. He batted and threw right-handed.[1]

Post playing career

After his retirement, Nichols earned his charter boat license and captained fishing tours, but he chose to return to baseball because, "When you own your own business, the customer is the boss and that is a lot of pressure."[2] Roland Hemond, his general manager (GM) from Chicago who had since assumed the same post with the Orioles, hired Nichols and assigned him to work with Doug Melvin as a field coordinator and coach.[2]

When Melvin became the Rangers' GM in 1994, he brought Nichols along.[2] Nichols served as the farm director for the Rangers from 1994 to 2000. In 2001, he served as the Rangers' first base and outfield coach.[42] With Texas, Nichols instituted a program to teach Ranger prospects etiquette and financial literacy, having actors role-play common scenarios that a rookie might encounter. "If a player walks into a bar on a road trip, everyone knows who they are,” said Nichols. “It’s important they know how to handle themselves in that situation."[43] The Wall Street Journal featured the program on the front page of its March 2, 1998 edition.[2]

When Melvin went from being GM of the Rangers to being GM of the Brewers before the 2002 season, he brought Nichols along as the Farm Director/Director of Player Development. Over the next several years, the Brewers farm system went from one of the lowest-ranked development systems to a number seven ranking in 2007 from Baseball Prospectus, developing players such as Ryan Braun, Prince Fielder, and Rickie Weeks. On whether it was better to have one or two elite prospects in a thin system or a system with more depth, Nichols said, "If you’re putting together a roster, you need depth. If you need a player or two to move up and fill slots, you want elite players."[42] Among his duties was personally notifying players who were released by the organization. "I like to have a good impact on a young person’s life. If someone wasn’t going to make it in the big leagues, I felt like we were doing them a favor to help them get their life going outside of baseball. I would sit with them all and talk to them about it."[2] David Stearns, who was hired as the team's GM after the 2015 season, did not renew Nichols's contract, ending his 14-year tenure with the team.[44]

For the next three years, Nichols helped with minority baseball camps in Vero Beach, Florida, sponsored by MLB and USA Baseball. Just a coach at first, he eventually became the person in charge of the whole operation. "I really enjoyed coaching. It’s the same successful feeling as playing when you see someone get what you’re teaching them," Nichols said.[2] He retired in 2018, the year he turned 60.[2]

Personal life

Nichols and his first wife, Janet, had three daughters: Amanda, Erin, and Kendall, the latter of whom went on to play volleyball at Liberty University.[2][45] He and his current wife, Elaine, live in Goodyear, Arizona. His hobbies include fishing, golfing, and hunting.[2] Nichols stands 6 feet 0 inches (1.83 m) and weighs 195 pounds (88 kg).[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 "Reid Nichols Stats". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on September 4, 2021. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Perry, Matthew. "Reid Nichols". SABR. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "Reid Nichols Minor Leagues Statistics & History". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ↑ "1979 Carolina League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ↑ "1980 International League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ↑ "Cleveland Indians at Boston Red Sox Box Score, September 16, 1980". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ↑ "Reid Nichols 1980 Batting Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on September 4, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ↑ "Tanana Beats Yanks". The Lewiston Daily Sun. April 3, 1981. p. 25. Archived from the original on May 23, 2021. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ↑ "Rick Miller 1981 Batting Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ↑ "Year in Review: 1981". Baseball Almanac. Archived from the original on June 4, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ↑ Harris, Steve (March 11, 1982). "Nichols Just Wants to Play". The Boston Herald.

- ↑ "Reid Nichols 1982 Batting Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ↑ “Nichols Is Getting Houk’s Attention,” The Sporting News, July 5, 1982: 22.

- ↑ "Boston Red Sox at Seattle Mariners Box Score, August 23, 1982". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ↑ Dick Trust, “Reid Nichols: A Gold-Plated Fill-In for the Sox,” Quincy (Massachusetts) Patriot Ledger, August 26, 1982

- ↑ Tom Yantz, “Red Sox’ Plans for Nichols Change,” Hartford Courant, March 29, 1983: C1.

- ↑ P.J. Conway, “Boston’s Nichols Ready to Help in Reserve Role,” Waterbury (Connecticut) Republican, March 22, 1983: C1.

- ↑ "Reid Nichols 1983 Batting Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ↑ "Tony Armas 1983 Batting Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ↑ "California Angels at Boston Red Sox Box Score, May 9, 1983". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ↑ "Boston Red Sox at Chicago White Sox Box Score, May 25, 1983". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ↑ "Reid Nichols 1984 Batting Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- 1 2 Chass, Murray (June 12, 1984). "Yankees Defeated by 6-run Ninth Inning". The New York Times. p. B7. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ↑ Smith, Claire (April 22, 1984). "Underpowering Tanana a Master of the Unexpected". Hartford Courant. Retrieved October 19, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Reid Nichols 1985 Batting Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ↑ "Oakland Athletics at Boston Red Sox Box Score, May 10, 1985". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on November 22, 2020. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ↑ "Oakland Athletics 5, Boston Red Sox 4". Retrosheet. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ↑ "Cleveland Indians at Chicago White Sox Box Score, July 18, 1985". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ↑ "Win No. 300 for Seaver meant to be". Daily Record. August 5, 1985. p. 27. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Reid Nichols 1986 Batting Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ↑ "Boston Red Sox at Chicago White Sox Box Score, April 12, 1986". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ↑ "Kansas City Royals at Chicago White Sox Box Score, May 16, 1986". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ↑ "Seattle Mariners at Chicago White Sox Box Score, September 30, 1986". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on August 2, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ↑ "Seattle Mariners at Chicago White Sox Box Score, October 1, 1986". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on August 2, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- 1 2 "Reid Nichols 1987 Batting Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on August 2, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ↑ Anderson, Dave (May 5, 1987). "Sports of the Times; Nobody Wanted Raines". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved January 19, 2008.

- ↑ "Houston Astros at Montreal Expos Box Score, May 9, 1987". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ↑ "Morris after consistency as Detroit Tigers' leader". The Rome News-Tribune. March 24, 1988. p. 3B. Archived from the original on May 23, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ↑ Meece, Volney (August 4, 1988). "89ers Minor Setback For Nichols". The Daily Oklahoman. Retrieved October 19, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Lubinsky, Tim (August 10, 1988). "Hanging on to glory days". The Tampa Tribune. Retrieved October 19, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Ivey, Mike (March 27, 1989). "Bout with cancer alters outlook of Cubs' Jackson". The Capital Times. Madison, WI. Retrieved October 19, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 David Laurila (March 4, 2007). "Prospectus Q&A: Reid Nichols". Baseball Prospectus. Archived from the original on April 29, 2007. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ↑ McCartney, Scott (March 2, 1998). "Pro Team Covers All It [sic] Bases With Rookie Education Course". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 2, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ↑ Haudricourt, Tom (October 13, 2015). "Reid Nichols let go, Gord Ash removed from role as Brewers restructure". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Archived from the original on October 15, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Getting To Know The Lady Flames: Kendall Nichols". Liberty University. October 18, 2006. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

External links

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs

- Retrosheet