Reo[1][2] is a domain-specific language for programming and analyzing coordination protocols that compose individual processes into full systems, broadly construed. Examples of classes of systems that can be composed with Reo include component-based systems, service-oriented systems, multithreading systems, biological systems, and cryptographic protocols. Reo has a graphical syntax in which every Reo program, called a connector or circuit, is a labeled directed hypergraph. Such a graph represents the data-flow among the processes in the system. Reo has formal semantics, which stand at the basis of its various formal verification techniques and compilation tools.

Definitions

In Reo, a concurrent system consists of a set of components which are glued together by a circuit that enables flow of data between components. Components can perform I/O operations on the boundary nodes of the circuit to which they are connected. There are two kinds of I/O operations: put-requests dispatch data items to a node, and get-requests fetch data items from a node. All I/O operations are blocking, which means that a component can proceed only after its pending I/O operation has been successfully processed.

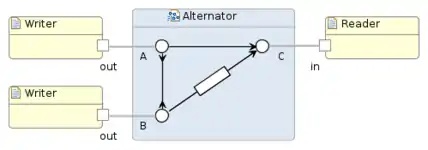

The figure on the top-right shows an example of a producers-consumer system with three components: two producers on the left and one consumer on the right. The circuit in the middle defines the protocol, which states that the producers should send data synchronously, while the consumer receives those data in alternating order.

Formally, the structure of a circuit is defined as follows:

Definition 1. A circuit is a triple where:

- N is a set of nodes;

- is a set of boundary nodes;

- is a set of channels;

- assigns a types to every channel.

such that , for all . If is a channel, then I is called the set of input nodes of c and O is called the set of output nodes of c.

The dynamics of a circuit resemble the flow of signals through an electronic circuit.

Nodes have fixed merger-replicator behavior: the data of one of the incoming channels is propagated to all outgoing channels, without storing or altering the data (i.e., replicator behavior). If multiple incoming channels can provide data, the node makes a nondeterministic choice among them (i.e., merger behavior). Nodes with only incoming or outgoing channels are called sink nodes or source nodes, respectively; nodes with both incoming and outgoing channels are called mixed nodes.

In contrast to nodes, channels have user-defined behavior represented by their type. This means that channels may store or alter data items that flow through them. Although every channel connects exactly two nodes, these nodes need not to be input and output. For instance, the vertical channel in the figure on the top-right has two inputs and no outputs. The channel type defines the behavior of the channel with respect to data. Below is a list of common types:

- Sync: Atomically gets data from its input node and propagates it to its output node.

- LossySync: Same as Sync, but can lose data if its output node is not ready to take data.

- Fifo⟨n⟩: Gets data from its input node, temporarily stores it in an internal buffer of size n, and propagates it to its output node (whenever this output node is ready to take data).

- SyncDrain: Atomically gets data from both its input nodes and loses it.

- Filter⟨c⟩: Atomically gets data from its input node and propagates it to its output node if the filter condition c is satisfied; loses the data otherwise.

Software engineering properties

Exogeneity

One way to classify coordination languages is in terms of their locus: locus of coordination refers to where coordination activity takes place, classifying coordination models and languages as endogenous or exogenous.[3] Endogenous models and languages, such as Linda, provide primitives that must be incorporated within a computation for its coordination. In applications that use such models, primitives that affect the coordination of each module are inside the module itself. In contrast, Reo is an exogenous language that provides primitives that support coordination of entities from without. In applications that use exogenous models, primitives that affect the coordination of each module are outside the module itself.

Endogenous models are sometimes more natural for a given application. However, they generally lead to an intermixing of coordination primitives with computation code, which entangles the semantics of computation with coordination protocols. This intermixing tends to scatter communication/coordination primitives throughout the source code, making the cooperation model and the coordination protocol of an application nebulous and implicit: generally, there is no piece of source code identifiable as the cooperation model or the coordination protocol of an application, that can be designed, developed, debugged, maintained, and reused, in isolation from the rest of the application code. On the other hand, exogenous models encourage development of coordination modules separately and independently of the computation modules they are supposed to coordinate. Consequently, the result of the substantial effort invested in the design and development of the coordination component of an application can manifest itself as tangible "pure coordinator modules" which are easier to understand, and can also be reused in other applications.

Compositionality / reusability

Reo circuits are compositional. This means that one can construct complex circuits by reusing simpler circuits. To be more explicit, two circuits can be glued together on their boundary nodes to form a new joint circuit. Unlike many other models of concurrency (e.g., pi-calculus), synchrony is preserved under composition. This means that if we compose a circuit with synchronous flow between nodes A and B with another circuit with synchronous flow between nodes B and C, the joint circuit has synchronous flow between nodes A and C. In other words, the composition of two synchronous circuits yields a synchronous circuit.

Semantics

The semantics of a Reo circuit is a formal description of its behavior. Various semantics for Reo exist.[4]

Historically the first semantics of Reo was based on the coalgebraic notion of streams (i.e., infinite sequences).[5] This semantics is based on the concept of a timed data stream, which is a pair consisting of a stream of data items and a stream of monotonically increasing time stamps (real numbers). By associating every node with such a timed data stream, the behavior of a channel can be modeled as a relation on the streams on the connected nodes.

Later, an automaton-based semantics was developed, which is called constraint automata.[6] A constraint automaton is a labeled transition system, where transition labels consist of a synchronization constraint and a data constraint. A synchronization constraint specifies which nodes synchronize in the execution step modeled by the transition, and a data constraint specifies which data items flow on these nodes.

One limitation of constraint automata (and timed data streams) is that they cannot directly model context-sensitive behavior, where the behavior of a channel depends on the (un)availability of a pending I/O operation. For example, using constraint automata, it is impossible to directly model the behavior of a LossySync, which should lose data only if its output node has no pending get-request. To solve this problem, another semantics of Reo has been developed, called connector coloring.[7]

Other semantics for Reo make it possible to model timed[8] or probabilistic[9] behavior.

Implementations

The Extensible Coordination Tools (ECT) are a set of plug-ins for Eclipse that constitute an integrated development environment (IDE) for Reo. The ECT consists of a graphical editor for drawing circuits and an animation engine for animating data-flow through circuits. For code generation, the ECT contains a Reo-to-Java compiler, which generates code for circuits based on their constraint automaton semantics. In particular, on input of a Reo circuit, it produces a Java class, which simulates the constraint automaton that models the circuit. For verification, the ECT contains a tool that translates Reo circuits to process definitions in mCRL2. Users can subsequently use mCRL2 for model checking against mu-calculus property specifications. (Alternatively, the Vereofy model checker also supports verification of Reo circuits.)

Another implementation of Reo is developed in the Scala programming language and executes circuits in a distributed fashion.[10]

References

- ↑ Farhad Arbab: Reo: a channel-based coordination model for component composition. Mathematical Structures in Computer Science 14(3):329--366, 2004.

- ↑ Farhad Arbab: Puff, The Magic Protocol. In Gul Agha, Olivier Danvy, Jose Meseguer, editors, Talcott Festschrift, volume 7000 of LNCS, pages 169-206. Springer, 2011.

- ↑ Farhad Arbab: Composition of Interacting Computations. In Dina Goldin, Scott Smolka, and Peter Wegner, editors, Interactive Computation, pages 277-321. Springer, 2006.

- ↑ Sung-Shik Jongmans and Farhad Arbab: Overview of Thirty Semantic Formalisms for Reo. Scientific Annals of Computer Science 22(1):201-251, 2012.

- ↑ Farhad Arbab and Jan Rutten: A Coinductive Calculus of Component Connectors. In Martin Wirsing, Dirk Pattinson, and Rolf Hennicker, editors, Proceedings of WADT 2002, volume 2755 of LNCS, pages 34--55. Springer, 2003.

- ↑ Christel Baier, Marjan Sirjani, Farhad Arbab, and Jan Rutten: Modeling component connectors in Reo by constraint automata. Science of Computer Programming 61(2):75-113, 2006.

- ↑ Dave Clarke and David Costa and Farhad Arbab: Connector colouring I: Synchronisation and context dependency. Science of Computer Programming 66(3):205-225, 2007.

- ↑ Farhad Arbab, Christel Baier, Frank de Boer, and Jan Rutten: Models and temporal logical specifications for timed component connectors. Software and Systems Modeling 6(1):59-82, 2007.

- ↑ Christel Baier: Probabilistic Models for Reo Connector Circuits. Journal of Universal Computer Science 11(10):1718-1748, 2005.

- ↑ José Proença: Synchronous Coordination of Distributed Components. PhD thesis, Leiden University, 2011.