The Residencies of British India were political offices, each managed by a Resident, who dealt with the relations between the Government of India and one or a territorial set of princely states.

History

The Residency system has its origins in the system of subsidiary alliances devised by the British after the Battle of Plassey in 1757, to secure Bengal from attack by deploying East India Company troops of the Bengal Army within friendly Native States.[1] Through this system, the Indian Princes of these Native States were assured of protection from internal or external aggression, through deployment of company troops. In return they had to pay for the maintenance of those troops and also accept a British Resident in their court. The Resident was a senior British official posted in the capital of these Princely States, technically a diplomat but also responsible for keeping the ruler to his alliance.[2] This was seen as a system of indirect rule that was carefully controlled by the British Resident. His role (and all were men) included advising in governance, intervening in succession disputes, and ensuring that the States did not maintain military forces other than for internal policing or else form diplomatic alliances with other States.[2][3] The Residents attempted to modernize these Native States through promotion of European notions of progressive government.[2]

The first Native States to enter such subsidiary alliances included Arcot, Oudh and Hyderabad.[2] Before the Rebellion of 1857, the role of the British Resident in Delhi was more important than that of other Residents, because of the tension that existed between the declining Mughal Empire and the emerging power of the East India Company.[4] After the establishment of Crown rule of British India in 1858, the indigenous States ruled by the Indian princes retained their internal autonomy in terms of political and administrative control, while their external relations and defence became the responsibility of the Crown. An area over two-fifths of the Indian subcontinent was administered by native princes,[5] although nothing like such a high proportion in terms of population.

The continuation of Princely rule allowed the British to concentrate their resources on the more economically significant areas under their direct control and also obscured the effective loss of independence of these States in their external relations.[2]

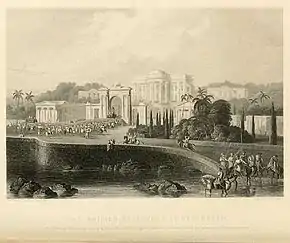

The Resident was a permanent reminder of the subsidiary relationship between the indigenous ruler and the European power.[3] The physical manifestation of this was the Residency itself, which was a complex of buildings and land modified according to the aesthetic values of the suzerain power. The Residency was a symbol of power because of its size and position within the prince's capital.[6] In many instances, the local prince even paid for the erection of these Residencies, as a gesture of his support for and allegiance to the British. The Nawab of Oudh, one of the richest native princes, paid for and erected a splendid Residency in Lucknow as a part of a wider programme of civic improvements.[5]

List of Residencies

North India

- Kashmir Residency

Part of Central India Agency

Part of Rajputana Agency

- Jaipur Residency

- Mewar Residency at Udaipur

- Western Rajputana States Residency

Other Residencies

- Mysore Residency

- Gwalior Residency

- Hyderabad Residency

- Persian Gulf Residency, for the British protectorates – Trucial States (1892–1971), Bahrain (1892–1971), Muscat and Oman, Kuwait (1914–1961) and Qatar (1916–1971)

Former Residencies

- Baroda Residency merged into Baroda and Gujarat States Agency in 1937

- Kolhapur Residency merged into Deccan States Agency in 1933

- Aden Residency (1859–1873), British territory in Yemen, placed under the Bombay Presidency till 1932, then directly as a Chief Commissioner's Province of India until 1937

See also

- Agencies of British India

- List of British residents or political agents in Delhi, 1803–57

- Siege of Lucknow - the prolonged defence of the Residency within the city of Lucknow during the Indian Rebellion of 1857.[7]

References

- ↑ Spear, Percival, India: A Modern History (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan, 1961); Spear, Percival, The Oxford History of Modern India : 1740–1947 (London: Oxford University Press, 1965)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Metcalf, Barbara D., and Thomas R. Metcalf, A Concise History of India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002)

- 1 2 King, Anthony D., Colonial Urban Development: Culture, Social Power and Environment (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1976)

- ↑ Gupta, Narayani, Delhi Between Two Empires 1803–1931: Society, Government and Urban Growth (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1981)

- 1 2 Davies, Philip, Splendours of the Raj: British Architecture in India, 1660–1947 (New York: Penguin Books, 1987

- ↑ Nilsson, Sten, European Architecture in India 1750–1850 (New York: Taplinger Publishing Company, 1969)

- ↑ Cassell's illustrated history of India