Richard Gibson | |

|---|---|

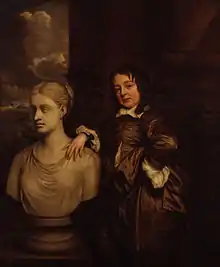

A portrait of Gibson with a classical bust, painted by Peter Lely | |

| Born | 1615 |

| Died | July 23, 1690 |

| Nationality | English |

| Known for | Painting |

Richard Gibson (1615-1690), known as "Dwarf Gibson", was a British painter of portrait miniatures and a court dwarf in England during the reigns of Charles I, Oliver Cromwell, Charles II, and William III and Mary II.

Both Andrew Marvell and Edmund Waller wrote poems addressed to him.

Life

His early life is undocumented, but he is said to have been a page in the service of a lady in Mortlake, who recognised his artistic talent. She supported him to study art under Francis Cleyn, director of design at the Mortlake Tapestry Works.[1] In the 1630s, Gibson was working for Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of Pembroke, who was the Lord Chamberlain. He is referred to as "little Dick, my lord Chamberlain's page" in notebooks recording a number of copies he made of existing paintings in royal and aristocratic collections. At the same time he was producing original portrait paintings for aristocratic clients. Herbert was his most important early patron, and may have introduced him to Peter Lely, with whom Gibson would enjoy a close and productive relationship. Lely painted several portraits of Gibson.[1]

Gibson was appointed "Page of the Back Stairs" under Charles I. During the English Civil War Gibson stayed in London with Pembroke, and thus became associated with the Parliamentary faction. By the 1650s Gibson appears to have been closely linked to Charles Dormer, 2nd Earl of Carnarvon, grandson of the Earl of Pembroke.[2] During Cromwell's regime he remained active as a painter at the Protector's court. However, Gibson's patrons in the 1650s are typically Royalists, but generally of the faction that had been supporters of parliament early in the war.[2]

His association with Cromwell did not affect his career under Charles II. Gibson was employed as drawing-master to Princess Mary and Princess Anne, the daughters of Charles' brother James (later King James II). He went with Mary to the Netherlands for her marriage to William of Orange in 1677. He came back to England in 1688 when William and Mary became monarchs after the overthrow of James II.

Family

Gibson married Anne Shepherd, who was known as the "queen's dwarf", as she was in the service of Queen Henrietta Maria. The couple were both said to be 3 ft 10 inches tall. The wedding was held at court, and the bride was given away by King Charles I. The event was the occasion of a poem by Edmund Waller, in which the pair are described as literally made for each other ("Design or chance make others wive, / But nature did this match contrive").

The couple had nine children, of whom three became successful painters. The best known of these was Gibson's daughter Susan, who also worked as a miniature painter, using her married name of Susan Penelope Rosse.[3] All the Gibson children were of typical size.

Style

The Grove Dictionary of Art states that "the miniatures assigned to Gibson are characterized by the thick pigment and parallel striations that give his work an impastoed quality".[1] His colours are typically soft and muted, anticipating the miniaturists of the 18th century. During the 1650s Gibson may have become so successful that he had to employ assistants, suggested by the existence of "Gibson-style but not Gibson-quality works" at this period. His children might have learned their skills this way.[2] He also seems to have been adopting a "brighter palette" at this time, to suit the tastes of the Restoration court.[2] William Sanderson's book Graphice (1658) describes Gibson as one of the most eminent of modern "limners".

Art historians John Murdoch and V. J. Murrell say that the distinguishing feature of Gibson's style is the "diagonal striation in the flesh painting".

Even by the naked eye, the coloured strokes of the brush over the carnation ground can be seen to consist of long broad hatches, which have often the tendency, especially in the flat plane of the forehead and the shadowing of the throat below the chin line, to move in diagonal parallel groups of hatches, stroked downwards from right to left....[Gibson's paint] is "impasted" in the manner of oil painting and is quite different from the traditionally transparent and linear technique of the limners.[2]

These techniques probably imply the influence of Lely. His adoption of a more "wide eyed" look in his Restoration-era works may also show the influence of Lely.[2]

Marvell poem

Andrew Marvell, in his mock epic poem The Third Advice to a Painter, addresses Gibson, joking on the fact that the artist who painted miniatures was himself of miniature stature. He refers to him as the "admiral" of his "navy small, of marshalled shells", whose small-scale works demonstrate by "drawing in little, how we do yet less". The poem becomes an extended satire on recent political and military events, especially the Second Anglo-Dutch War. Marvell suggests that Gibson should paint miniaturised epic works about events, to represent the minuscule achievements of the real admirals and statesmen in the war. Lely could not paint the works because he is tainted by his own Dutch origin, but Gibson represents authentically tiny English aspirations.[4]

DG monogram

It has been argued that a number of miniatures signed with the monogram "DG" are the work of Gibson, on the grounds that they are "stylistically inseparable" from his known work of a later period, which is usually signed "RG". The "DG" miniatures appear to date from the artist's early career when no examples of his work with his usual "RG" monogram are known. If this is so, it is possible that the artist proudly adopted the nickname "Dwarf Gibson" as his signature. Alternatively, it may have stood for "Dick Gibson", the version of his name by which he was known in his youth.[2]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Richard Gibson, Grove Dictionary of Art

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 John Murdoch and V. J. Murrell, "The Monogramist DG: Dwarf Gibson and His Patrons", The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 123, No. 938, May, 1981

- ↑ Saywell, David; Simon, Jacob, National Portrait Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, 2004, p. 245.

- ↑ Nigel Smith (ed), The Poems of Andrew Marvell, Pearson Education, 2007, pp.244ff.