| Riley's Lock | |

|---|---|

Riley's Lock and lockhouse | |

| 39°04′09″N 77°20′27″W / 39.069167°N 77.340877°W | |

| Waterway | Chesapeake and Ohio Canal |

| Country | USA |

| State | Maryland |

| County | Montgomery |

| Operation | Defunct |

| Towpath milemarker 22.7 | |

Riley's Lock (Lock 24) and lock house are part of the 184.5-mile (296.9 km) Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (a.k.a. C&O Canal) that operated in the United States along the Potomac River from the 1830s through 1923. They are located at towpath mile-marker 22.7 adjacent to Seneca Creek, in Montgomery County, Maryland. The lock is sometimes identified as Seneca because of the Seneca Aqueduct that carried the canal over the creek to the lift lock. The name Riley comes from John C. Riley, who was lock keeper from 1892 until the canal closed permanently in 1924.

The lock, lock house, and aqueduct attached to the lock were built in the early 1830s. Construction of Aqueduct 1 and other aqueducts further upriver took longer than other downriver portions of the canal, causing the first phase of canal operation to be between Georgetown and Lock 23. Construction of the entire canal was completed in 1850, and connected Cumberland in Western Maryland with Georgetown on the Potomac River. The canal was necessary because portions of the Potomac River upstream from Georgetown were not navigable.

Today, Riley's Lock is part of Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park. The site is the only place on the canal that has a lift lock connected to an aqueduct. Picnic tables, restrooms, parking, and a canoe ramp are on site. Ruins of the Seneca Stone Cutting Mill are less than 0.25 miles (0.40 km) away. The lock and surrounding area are known as excellent places for bird watching, and the 40-acre (16 ha) Dierssen Waterfowl Sanctuary is about two miles (3.2 km) away.

Background

Ground was broken for construction of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (a.k.a. C&O Canal) on July 4, 1828.[1] One of the early plans was for the canal to be a way to connect the Chesapeake Bay with the Ohio River—hence the name Chesapeake and Ohio Canal.[2] The canal has several types of locks, including 74 lift locks necessary to handle a 605-foot (184 m) difference in elevation between the two canal ends—an average of about 8 feet (2.4 m) per lock.[3] The canal also has 11 aqueducts, and the Seneca Aqueduct at the Lock 24 location is the first aqueduct when traveling up the canal.[4] From Georgetown to Harpers Ferry (includes Lock 24, Riley's Lock), the canal is 60 feet (18 m) wide at the surface, and 42 feet (13 m) at the bottom. Including walls, lift locks are 100 feet (30 m) long and 15 feet (4.6 m) wide—usable lockage was closer to 88 feet (27 m) long and 14.5 feet (4.4 m) wide.[5][6] Some canal boats could carry over 110 tons (99.79 metric tons) of coal.[6]

Portions of the canal (close to Georgetown) began operating in the early 1830s, and construction ended in 1850 without reaching the intended Ohio River termination.[7] Upon completion, the canal ran from Georgetown to Cumberland, Maryland. The canal was necessary since portions of the Potomac River, especially at Great Falls, could not serve for reliable navigation because the river can be shallow and rocky as well as subject to low water and floods.[8] The canal opened the region to important markets and lowered shipping costs. By 1859, about 83 canal boats per week were transporting coal, grain, flour, and farm products to Washington and Georgetown.[9] Tonnage peaked in 1871 as coal trade increased.[10]

The canal faced competition from other modes of transportation, especially the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O Railroad). Starting in Baltimore and adding line westward, the B&O Railroad eventually reached the Ohio River and beyond, while the C&O Canal never went beyond Cumberland in Western Maryland.[1] An economic depression during the mid-1870s, and major floods in 1877 and 1886, put a financial strain on the C&O Canal Company.[10] In 1889, another flood produced an estimated $1 million (equivalent to $32,570,370 in 2022) in damages and caused the company to enter bankruptcy.[11][12] Operations stopped for about two years. Court-appointed trustees recommended by the B&O Railroad took over receivership of the canal and began operating it under court supervision, but canal use never recovered to the peak years of the 1870s.[13] The C&O Canal closed for the season in November 1923.[14] Severe flooding in 1924 prevented the canal from opening in the spring, and the resulting damage from the floods prevented it from opening during the entire year.[15] The flood damage, combined with continued competition from railroads and trucks, caused the shutdown to be permanent.[16] In 1938, the canal was sold to the United States government, and the canal was proclaimed a national monument in 1961.[10]

History

.jpg.webp)

Work on Lock 24 began in March 1829 and was completed March 1832 at a cost of $8,886.88 (equivalent to $260,504 in 2022).[17] The lock was made from Seneca Creek Red Sandstone boated down the Potomac River from the Seneca Quarry.[18] Construction of the lock house began in November 1829, and was finished April 1830 at a cost of $1,066.25 (equivalent to $29,302 in 2022).[19] By June 1832, a 22-mile (35 km) section of the canal was operating between Georgetown and Lock 23.[20] The Seneca Aqueduct, Aqueduct No. 1, was completed April 1832 at a cost of $24,340.25 (equivalent to $713,494 in 2022).[21] The next two aqueducts upriver, No. 2 and No. 3, were completed in May 1833 and February 1834, respectively.[21] It was not until 1833 that a dam at Harpers Ferry was completed and enabled the canal to operate above Lock 23.[22] Riley's Lock is unique because it has a combination of an aqueduct and lift lock. The Seneca Aqueduct carries canal boats over Seneca Creek directly to the lift lock.[4]

Some C&O Canal records remain, allowing some of the lock keepers to be identified. Charles H. Shanks was listed as lock keeper on July 1, 1839.[23] He was still listed as lock keeper on May 31, 1842.[24] John Wells was lock keeper on May 31, 1845, and was still lock keeper at the end of 1850.[25][26] Charles Wood is listed as Lock 24 tender circa 1865.[27] An 1865 map of Montgomery County, Maryland, confirms Wood as the lock keeper by showing "Chas. Wood L.K." (lock keeper) at a point on the canal near Seneca Creek.[28] The map also shows a "J.W. Darby's" near the creek and canal, and John Darby and Son (Upton) were known to have a lease for a nearby warehouse granted in 1871.[28][29]

Civil War

At the beginning of the American Civil War, Union Army leadership realized that the Potomac River area near Locks 23 and 24 was a possible crossing point for a Confederate invasion that could include Washington. The small community of Darnestown, less than 4 miles (6.4 km) north of Lock 24, became occupied during 1861 by 18,000 Union troops.[30] About halfway between Lock 24 and Darnestown, Major General Nathaniel P. Banks kept his headquarters at the Samuel Thomas Macgruder farm where the Potomac River could be observed from high ground.[31]

On June 27, 1863, 5,000 cavalry troops under the command of Confederate General Jeb Stuart crossed the Potomac River near Lock 24. Intent on disrupting Union supply lines, they seized the canal between Locks 23 and 24, and damaged lock gates, drained water from the canal, and burnt canal boats. From there, they advanced to Rockville, Maryland, before rejoining General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia in the Battle of Gettysburg.[32]

Riley family

William H. Riley came to America from Ireland around 1849, and found work at the Seneca quarry. By 1880 he was working on the C&O Canal, as was his oldest son, John C. Riley. John married in 1890 and began working at the same quarry where his father worked years earlier. During 1892, the quarry shut down, but John was able to replace William Benson as lock tender for Lock 24.[33]

The family lived in the lock house until 1905 when a young daughter drowned in the canal. After the tragedy, John's wife Roberta and the children moved up the hill (at River Road) while John stayed at the lock house. Family members would visit the lock house daily, but at nighttime were always back to the safety of the house on the hill. Riley would sometimes rent the extra lock house rooms to campers.[34] In November after the canal closed for the season, he would live with the family at the house on the hill until the canal reopened in March.[35]

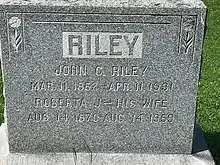

The canal was closed permanently in 1924, but Riley continued working near the lock. The 1930 U.S. Census lists him as a canal watchman, and the family had a boat rental business that lasted until the 1940s.[36][37] At the age of 69, John Riley died suddenly at his home on April 11, 1931, and was buried at the Darnestown Presbyterian Church cemetery.[38] Today, Lock 24 is known as Riley's Lock in honor of John Riley and the Riley family, and the road that leads to the lock is named Rileys Lock Road (without the apostrophe).[39]

Today

Riley's Lock and lock house are part of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park.[40] Congress authorized the establishment of the park, and acquisition of adjacent land, in 1971.[10] A Riley's Lockhouse History Program is run by local Girl Scouts through a special permit from the park. On weekends in the spring and fall, Girl Scouts give tours of the lock house during the afternoons.[41][42] Riley's Lock is also part of the Seneca Historic District listed in the National Register of Historic Places along with the Seneca Stone Cutting Mill, Seneca Quarry, and other nearby places.[43] The ruins of the Seneca Stone Cutting Mill are only 0.2 miles (0.32 km) west of the lock.[44]

The Maryland Ornithological Society lists the lock as one of the top birdwatching places in Montgomery County, with over 200 species sited.[45] In addition, the 40–acre (16 ha) Dierssen Waterfowl Sanctuary is not far away at towpath marker 20.0.[46] An outdoor education camp and the DC National Rowing Club are located nearby on Rileys Lock Road.[47][48] Although considered part of the tiny community of Seneca, the lock has a Poolesville address and is found in the Darnestown census-designated place near Seneca Creek by taking Rileys Lock Road off of Montgomery County's River Road.[49][50]

See also

Notes

Citations

- 1 2 "C&O Canal versus the B&O Railroad". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-06-09. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- ↑ Rubin 2003, p. 4

- ↑ "C&O Canal Lock 8 (Seven Locks)". National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2021-09-26. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- 1 2 "Riley's Lock & Seneca". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-09-26. Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 226

- ↑ "Canal History: Canal Era from the 1830s-1870s". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-06-09. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ↑ "Chesapeake & Ohio Canal". Visit Maryland, Maryland Office of Tourism Development. Maryland Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on 2019-12-28. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ↑ Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 18

- 1 2 3 4 "Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park". National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2020-08-15. Retrieved 2020-07-07.

- ↑ "Canal History: Flooding and Its Effects on the Canal". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-06-12. Retrieved 2020-07-19.

- ↑ "Chesapeake and Ohio Canal - The C&O Canal's Legal Status 1889–1939". National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2020-06-20. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- ↑ "Today in History - October 10 - The C&O Canal". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2020-06-20. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- ↑ "Canal to Close Season in Week". Daily Mail (Hagerstown, Maryland). 1923-11-13. p. 1.

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal will be closed this week or early next week for the winter season.

- ↑ "Close C and O Canal". Morning Herald (Hagerstown, Maryland). 1923-08-01. p. 1.

...will not be reopened this year. The canal was damaged by the two floods this spring, and an effort has been made for several months to repair its banks, but with little success.

- ↑ "Canal History: Decline and Eventual Closing of the C&O Canal". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-06-12. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 230

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 159

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 245

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 65

- 1 2 Unrau 2007, p. 239

- ↑ Romigh, Philip S.; Mackintosh, Barry (1979). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Chesapeake and Ohio Canal". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior (National Archives). Archived from the original on 2020-07-21. Retrieved 2020-07-21.

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 597

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 610

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 611

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 621

- ↑ "Chesapeake & Ohio Canal - Canal Workers". National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2020-06-28. Retrieved 2020-06-26.

- 1 2 Martenet & Bond (1865). Martenet and Bond's Map of Montgomery County, Maryland (Map). Baltimore, Maryland: Simon J. Martenet. Archived from the original on 2020-06-25. Retrieved 2020-06-29.

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 694

- ↑ Montgomery County Historical Society 1999, p. 9

- ↑ Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 216

- ↑ "Rowsers Ford". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2020-08-07.

- ↑ "Riley Family History Page 3". Western Maryland Historical Library. Archived from the original on 2021-09-26. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ↑ "Riley Family History Page 7". Western Maryland Historical Library. Archived from the original on 2021-09-26. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ↑ "Riley Family History Page 8". Western Maryland Historical Library. Archived from the original on 2021-09-26. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ↑ "Riley Family History Page 9". Western Maryland Historical Library. Archived from the original on 2021-09-26. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ↑ Meyer, Eugene L. (1987-02-20). "CO Canal a Special Place to Call Home". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2021-09-26. Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ↑ "Deaths - Riley, John C. (page A-9 lower right)". Washington Evening Star (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). 1931-04-13. Archived from the original on 2021-09-26. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ↑ "Riley's Lock & Seneca". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-09-26. Retrieved 2020-08-06.

- ↑ "C&O Canal Hike 10". National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2020-06-15. Retrieved 2020-07-16.

- ↑ Oman, Anne H. (1985-02-15). "Reliving the Lockhouse Life". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2021-09-26. Retrieved 2020-08-07.

- ↑ "Riley's Lockhouse (Girl Scouts)". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-08-15. Retrieved 2020-08-07.

- ↑ Muir, Dorthy; Kephart, Mary Ann; Kiplinger, Austin (Historic Medley District, Inc.) (1975). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Seneca Historic District". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior (Maryland Historical Trust). Archived from the original on 2021-09-26. Retrieved 2020-08-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Seneca Stone Cutting Mill". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-10-30. Retrieved 2020-08-07.

- ↑ "Birder's Guide to Maryland and DC - C&O Canal – Pennyfield, Violette's & Riley's Locks". The Maryland Ornithological Society. Archived from the original on 2020-06-28. Retrieved 2020-08-06.

- ↑ "Dierssen Waterfowl Sanctuary". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-08-12. Retrieved 2020-08-07.

- ↑ "Home - Calleva Outdoors I Summer Camp and Year Round Adventures". Calleva. Archived from the original on 2021-04-30. Retrieved 2021-04-30.

- ↑ Club, DC National Rowing. "DC NATIONAL ROWING CLUB". DC National Rowing Club. Archived from the original on 2021-04-30. Retrieved 2021-04-30.

- ↑ "Riley's/Seneca Parking". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-08-10. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ↑ "Travilah, CDP, Maryland (map)". United States Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau, United States Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on 2020-07-22. Retrieved 2020-07-22.

References

- Balkan, Evan (2008). The Best in Tent Camping: A Guide for Car Campers Who Hate RVs, Concrete Slabs, and Loud Portable Stereos. Birmingham, Alabama: Menasha Ridge Press. ISBN 978-0-89732-755-8. OCLC 1015877303.

- Hullfish, Bill; Ruch, Dave (2019). The Erie Canal Sings: A Musical History of New York's Grand Waterway. Chicago, Illinois: Arcadia Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-1-43966-713-2. OCLC 1104726854.

- Kelly, Clare Lise; Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission (2011). Places from the Past: The Tradition of Gardez Bien in Montgomery County, Maryland - 10th Anniversary Edition (PDF). Silver Spring, Maryland: Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission. ISBN 978-0-97156-070-3. OCLC 48177160. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-12. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- Kytle, Elizabeth (1996). Home on the Canal. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-80185-328-9. OCLC 1048227577.

- Lowman, Jeff (2015). Paddling Maryland and Washington, DC : A Guide to the Area's Greatest Paddling Adventures. Guilford, Connecticut: FalconGuides. ISBN 978-1-49301-492-7. OCLC 920824361.

- Montgomery County Historical Society (1999). Montgomery County, Maryland – Our History and Government (PDF). Rockville, Maryland: Montgomery County Government Office of Public Relations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-05-05. Retrieved 2021-09-10.

- Rubin, Mary H. (2003). The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia. ISBN 978-1-43961-250-7. OCLC 904439352.

- Unrau, Harlan D. (2007). Historic Resource Study: Chesapeake & Ohio Canal (PDF). Hagerstown, Maryland: National Park Service - United States Department of Interior. OCLC 184689456. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-05-09. Retrieved 2020-08-07.

- U.S. National Park Service Division of Publications (1991). Chesapeake and Ohio Canal: A Guide to Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park, Maryland, District of Columbia, and West Virginia. Washington, District of Columbia: United States Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780912627434. OCLC 1020193560. Archived from the original on 2021-09-10. Retrieved 2020-08-07.

- Welles, Judith (2019). Potomac. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-46710-436-4. OCLC 1111392250.

- Youth, Howard (2014). Field Guide to the Natural World of Washington, D.C. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-42141-203-0. OCLC 903126664.