Robert Furman | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Robert R. Furman | |

| Birth name | Robert Ralph Furman |

| Born | August 21, 1915 Trenton, New Jersey |

| Died | October 14, 2008 (aged 93) Adamstown, Maryland |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1940–1946 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | World War II: |

| Other work | Founder of Furman Builders Inc |

Robert Ralph Furman (August 21, 1915 – October 14, 2008) was a civil engineer who during World War II was the chief of foreign intelligence for the Manhattan Engineer District directing espionage against the German nuclear energy project. He participated in the Alsos Mission, which conducted a series of operations with the intent to place all uranium in Europe into Allied hands, and at the end of the war rounded up German atomic scientists to keep them out of the Soviet Union. He personally escorted half of the uranium-235 necessary for the Little Boy atomic bomb to the Pacific island of Tinian. He was also a key figure overseeing the construction of The Pentagon building. After the war he founded Furman Builders Inc., a construction company that built hundreds of structures, including the Potomac Mills shopping mall in Woodbridge, Virginia.

Early life

Furman was born on August 21, 1915, in Trenton, New Jersey, one of five sons of William and Leila Ficht Furman. His father was a bank teller, and his mother worked as a riveter during World War II. He attended Princeton University and graduated in 1937 with a degree in civil engineering. He then worked for the Pennsylvania Railroad and a construction company in New York.[1]

World War II

In December 1940, Furman was activated as a member of the United States Army Reserve and assigned to the Quartermaster Corps Construction Division, where he worked for Colonel Leslie R. Groves, Jr., supervising the day-to-day construction of The Pentagon. When the building was completed in 1943, Groves was reassigned to the "Manhattan Project" and brought his aide, Furman, with him.[1][2]

In August 1943 Furman was put in charge of an intelligence effort formed by Groves in response to concerns raised by atomic bomb project scientists about the German nuclear energy project. As director of intelligence, Furman was responsible for ascertaining the progress the Germans were making.[1] In December 1943, Groves sent Furman to Britain to discuss the establishment of a London Liaison Office for the Manhattan Project and the British government, and to confer over coordinating the intelligence effort.[3]

Furman sent the spy Moe Berg to Switzerland to meet the head of the German project, Werner Heisenberg. After chatting with Heisenberg at a cocktail party, Berg concluded that the Germans were a long way behind the Allied effort.[4] Furman travelled to Rome in June 1944, where he interviewed Italian scientists about the German project.[5]

When the Alsos Mission found documentation in office of Union Minière in Antwerp that indicated over 1,000 tons of refined uranium had been sent to Germany, but about 150 tons still remained at Olen, Belgium,[6] Groves sent Furman back to Europe with orders to secure the Olen cache. The Alsos Mission located 68 tons there, but another 80 tons was missing, having been shipped to France in 1940 ahead of the German invasion of Belgium.[7] Groves had the Olen uranium shipped to England and, ultimately, to the United States.[8]

Documentation indicated that the missing uranium had been sent to Toulouse.[9] An Alsos Mission team under Boris Pash's command reached Toulouse on October 1 and inspected a French Army arsenal with a Geiger counter. When the needle jumped near some barrels, they were inspected and found to be the 31 tons of uranium from Belgium. The 3342nd Quartermaster Truck Company was released from the Red Ball Express to retrieve the shipment.[10] The barrels were collected and transported to Marseilles, where Furman supervised their loading on a ship bound for the United States.[1]

In April 1945, Furman participated in Operation Harborage. The Alsos Mission and the 1269th Engineer Combat Battalion occupied Haigerloch, where they found and destroyed a German experimental nuclear reactor, and recovered uranium and heavy water.[11] The Alsos Mission took Heisenberg into custody on May 2.[12] Furman supervised his detention and that of nine other German scientists, who were taken to Rheims, then Versailles, and finally to the country estate of Farm Hall in England, where their conversations were monitored and where they could not defect to the Soviet Union.[4][13]

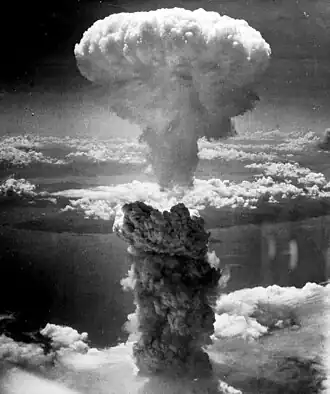

In July 1945, Furman personally escorted half of the uranium-235 necessary for the Little Boy atomic bomb to the Pacific island of Tinian. Accompanied by Captain James F. Nolan, a radiologist with Project Alberta, Furman set out by car from Santa Fe to Albuquerque on July 14, then travelled by air to Hamilton Field, California. The men boarded the cruiser USS Indianapolis at Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, and crossed the Pacific to Tinian, arriving on July 26.[14][15] A few days after leaving Tinian, the Indianapolis was torpedoed and sunk by a Japanese submarine with the loss of over 800 men.[1][16]

Later life

Furman left the army the year after the war ended and founded Furman Builders Inc. in Rockville, Maryland. The firm built hundreds of homes, schools and commercial buildings, including the Potomac Mills shopping mall in Woodbridge, Virginia, the Metropolitan Baptist Church in Washington, D.C., and the United States embassy in Nicaragua.[13] He married Mary Eddy in 1952.[4] They had four children: a son, David, and three daughters, Martha Keating, Julia Costello and Serena Furman.[1]

For the most part, Furman kept quiet about his exploits during the war. He served as president of the local Rotary Club and sang baritone in a barbershop quartet.[2][4] He retired in 1993, and died of metastatic melanoma on October 14, 2008, at Buckingham's Choice retirement community in Adamstown, Maryland, at the age of 93.[4][13]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hevesi, Dennis (October 29, 2008). "R. R. Furman, 93, Dies; Led Bomb-Project Spying". The New York Times. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- 1 2 "Robert Furman". TIME magazine. October 31, 2008. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ↑ Groves 1962, p. 194.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Carlson, Michael (January 23, 2009). "Robert Furman – He played a key role in the Manhattan project". The Guardian. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ↑ Groves 1962, pp. 209–210.

- ↑ Pash 1969, pp. 82–86.

- ↑ Groves 1962, pp. 219–220.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 287.

- ↑ Pash 1969, p. 98.

- ↑ Pash 1969, pp. 111–116.

- ↑ Pash 1969, pp. 207–210.

- ↑ Pash 1969, pp. 230–237.

- 1 2 3 "Robert Furman, secretive WWII figure, dead at 93". USA Today. October 31, 2008. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ↑ Russ 1990, p. 55.

- ↑ Groves 1962, pp. 305–306.

- ↑ Jones 1985, p. 536.

References

- Groves, Leslie (1962). Now it Can be Told: The Story of the Manhattan Project. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-306-70738-1. OCLC 537684.

- Jones, Vincent (1985). Manhattan: The Army and the Atomic Bomb (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 10913875. Retrieved February 25, 2012.

- Pash, Boris (1969). The Alsos Mission. New York: Charter Books. OCLC 568716894.

- Russ, Harlow W. (1990). Project Alberta: The Preparation of Atomic Bombs For Use in World War II. Los Alamos, New Mexico: Exceptional Books. ISBN 978-0-944482-01-8. OCLC 24429257.