Robert Morris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 8, 1823 |

| Died | December 12, 1882 (aged 59) |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Known for | Abolitionist |

Robert Morris (June 8, 1823 – December 12, 1882) was one of the first African-American attorneys in the United States,[1] and was called "the first really successful colored lawyer in America."[2]: 99

Biography

Early life

Morris was born on June 8, 1823, in Salem, Massachusetts.[1] At the age of 15, Morris went to work as a household servant for the abolitionist lawyer, Ellis Gray Loring. When Loring's regular copyist, a white youth, neglected his duties, Morris took over for him.[3] Impressed with Morris's intellect, Loring tutored him in the law, and in 1847 presented him for admission to the Massachusetts bar.[4]

Attorney

After his admission to the bar in 1847, Morris may have been the first black male lawyer to file a lawsuit in the U.S. He was also the first black lawyer to win a lawsuit.[2]: 96–97

According to some sources, Morris and Macon Bolling Allen opened America's first black law office in Boston,[5] but the authors of Sarah's Long Walk say there is "no direct knowledge that [Allen and Morris] ever met",[6] nor is such a partnership mentioned in Emancipation: The Making of the Black Lawyer, 1844-1944.

Abolitionist

Roberts v. Boston

Morris was active in black and abolitionist causes, notably filing and trying the first U.S. civil rights challenge to segregated public schools in the 1848 case of Roberts v. Boston. Morris and Charles Sumner pressed the case, which is believed to be the first legal challenge to the "separate but equal" practice of segregation in America. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled against Morris in 1850. The U.S. Supreme Court later cited the case in support of its Plessy v. Ferguson ruling in 1896, which codified the "separate but equal" standard. "Separate but equal" was ultimately overturned by the high court in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.

Fugitive Slave Act

Anthony Burns

Anthony Burns was a fugitive slave who was captured and tried under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 in Boston. Richard Henry Dana Jr. and Morris acted as Burns' attorneys, but were unsuccessful. With the ruling made against Burns, the government effectively held Boston under martial law for the afternoon. The case generated national publicity, large demonstrations, protests and an attack on US Marshals at the courthouse. Federal troops were used to ensure Burns was transported to a ship for return to Virginia after the trial. He was eventually ransomed from slavery, with his freedom purchased by Boston sympathizers. Afterward he was educated at Oberlin College and became a Baptist preacher, moving to Upper Canada for a position.[7]

Shadrach Minkins

Shadrach Minkins was a fugitive slave from Norfolk, Virginia, who escaped in 1850 to Boston, Massachusetts and worked as a waiter. He was captured and held under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. Upon his arrest at the restaurant where he worked, Minkins was taken to a hearing at the Boston courthouse. Morris worked with attorneys Samuel E. Sewall, Ellis Gray Loring, and Richard Henry Dana Jr. to defend Minkins. Seeking to have Minkins released from custody, they filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus with the Supreme Judicial Court, which was refused by Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw.[8]

Morris collaborated with Edward G. Walker and Lewis Hayden collaborated to obtain Minkins' release.[9] He was rescued by white and black members of the anti-slavery Boston Vigilance Committee.[8][10][11] After having been hidden in an attic in Beacon Hill, Minkins escaped and fled to Canada. Nine abolitionists were indicted, and charges were dismissed for some individuals. Morris and Lewis Hayden, who had stormed the courtroom to get Minkins, were tried and acquitted.[8]

Massasoit Guards

After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law, clothing retailer John P. Coburn founded an African-American militia unit called the Massasoit Guards to police Beacon Hill and protect residents from slave catchers. Morris repeatedly petitioned the Massachusetts legislature on their behalf, but the Massasoit Guards were never officially recognized or supported by the state. The group was a precursor to the 54th Massachusetts Regiment.[12]

School integration

Morris, Thomas Dalton, and William Cooper Nell argued the importance of integration in Boston schools: "It is very hard to retain self-respect if we see ourselves set apart and avoided as a degraded race by others ... Do not say to our children that however well-behaved their very presence is in a public school, is contamination to your children." Lastly, they said that black schools did not provide the same level of education as the multiple forms of white schools, including primary, grammar, Latin and high schools.[13]

Boston's African American community worked for educational opportunities as early as 1787, when Prince Hall petitioned for equal access to public schools to the legislature of Massachusetts. His and other attempts to gain access to schools were also denied. The Beacon Hill home of Hall's son, Primus Hall, was used as a school starting in 1798. Ten years later the school was moved to the African Meeting House. In the 1820s, the city government provided two primary schools for black children.[14] School conditions and teacher quality was not maintained by the Boston School Committee, and children of color were excluded from Boston's high school and Latin school. The efforts to create a separate but equal school system in Boston failed.[15]

Further career

Morris was commissioned as a magistrate of Essex County, Massachusetts, by the governor, making him the second black lawyer to hold a judicial post. He ran for mayor of Chelsea, Massachusetts, in 1866.

Personal life

Morris was married to Catherine Mason Morris, and they had a son, Robert Jr. Though raised a Black Methodist, Morris converted to his wife's religion of Catholicism in the 1850s.[16]

The Morris family eventually began worshipping at the Church of the Immaculate Conception in Boston’s South End, which was connected to Boston College. Morris established connections with early Boston College leaders, including Father Robert J. Fulton, S.J. In the summer of 1868, Morris traveled across Europe with his family and reminisced later about their experience riding in trains and staying in hotels without facing racial discrimination. During the trip, Morris, Catharine, and Robert Jr. stayed in Rome and had a personal audience with the Pope at the Vatican.[17]

Legacy

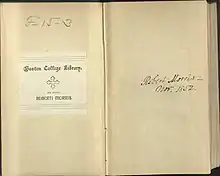

The Morris Library and Boston College

Morris was a book collector, and the extant part of his library is held by the John J. Burns Library (over 80 in number) and the Law Library (2 books) at Boston College. The Morris family had a strong relationship with Boston College in its earliest days. These books went to Boston College either after Morris's death in 1882, his widow Catharine's death in 1895, or both.[18] His law books, mentioned in his will, have not been located.[19]

An ongoing reconstruction of Morris's personal library is available on LibraryThing. Over 135 titles have been identified so far, including the extant books at Boston College and other titles listed in one of Morris's account books.[20]

References

- 1 2 "Morris, Robert, Sr. (1823–1882)". BlackPast.org. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- 1 2 Smith Jr., J. Clay; Marshall, Thurgood (1999). Emancipation: The Making of the Black Lawyer, 1844-1944. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1685-1.

- ↑ Smith, Jay Clay Jr. (1999). Emancipation: The Making of the Black Lawyer, 1844-1944. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 96. ISBN 9780812216851.

- ↑ "Fugitive Slave law". Massachusetts Historical Society.

- ↑ Manos, Nick (December 31, 2008). "Allen, Macon Bolling (1816-1894)". BlackPast.org. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ↑ Kendrick, Stephen & Kendrick, Paul (2004). Sara's Long Walk The Free Blacks of Boston and How Their Struggle for Equality Changed America. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Finkleman, Paul. "Anthony Burns (1834–1862)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved August 5, 2015.

- 1 2 3 The Ordeal of Shadrach Minkins. Archived May 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ↑ Edwin Garrison Walker. BlackPast.org. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ↑ Gary Collison, Shadrach Minkins: From Fugitive Slave to Citizen, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (1998 paperback reprint). pp. 83-87. ISBN 0-674-80299-3.

- ↑ The Ordeal of Shadrach Minkins. Archived October 27, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Black Heritage Trail (Boston African American National Heritage Site Park Brochure, Side 2)" (PDF). Boston African American National Historic Site (National Park Service); Museum of African American History. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ↑ Moss, Hilary J. (April 15, 2010). Schooling Citizens: The Struggle for African American Education in Antebellum America. University of Chicago Press. pp. 154–. ISBN 978-0-226-54251-5. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Site 13: Abiel Smith School, Museum of African American History, 46 Joy Street, Beacon Hill". Museum of African American History (Boston and Nantucket). Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ↑ White, Arthur O. (1973). "The Black Leadership Class and Education in Antebellum Boston". The Journal of Negro Education. 42 (4): 504–515. doi:10.2307/2966563. JSTOR 2966563.

- ↑ The black abolitionist papers. C. Peter Ripley. Chapel Hill. 2015. ISBN 978-1-4696-2438-9. OCLC 1062298283.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ "Religion and the Irish Community - Robert Morris - Law Library - Boston College". www.bc.edu. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ↑ Bauer, Avi, Mary Sarah Bilder, Laurel Davis, and Nick Szydlowski. "Robert Morris: Civil Rights Lawyer & Antislavery Activist." Boston College Law School.

- ↑ Davis, Laurel E., and Mary Sarah Bilder. "The Library of Robert Morris, Civil Rights Lawyer & Activist." Law Library Journal, Fall 2019: 461-508.

- ↑ Davis, Laurel E. "Robert Morris Legacy Library." LibraryThing.