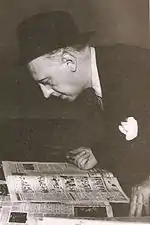

Roberto Noble | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 9 September 1902 La Plata, Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Died | 12 January 1969 (aged 66) Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Resting place | La Recoleta Cemetery |

| Alma mater | National University of La Plata |

| Occupation(s) | Politician, newspaper founder and director |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 1 |

Roberto Noble (9 September 1902 – 12 January 1969) was an Argentine politician, journalist and publisher, perhaps best known for having founded Clarín, long Argentina's leading news daily and the most or second-most circulated in the Spanish-speaking world.[1]

Life and times

Early career

Born to privilege in the city of La Plata, Roberto Noble developed a socialist ideology as an adolescent, having already earned some renown by 1918 agitating for the movement to reform Argentina's university system, whose curriculum had hitherto been largely dictated by conservative Catholics. Obtaining a Law Degree at the prestigious National University of La Plata, he joined the Socialist Party of Argentina, and later aligned himself with the dissident Independent Socialists. This party split from the Socialist Party to seek an alliance with conservatives sharing their distaste for the populist Hipólito Yrigoyen for the 1928 elections (which Yrigoyen won).[2]

Noble was a vocal advocate for the overthrow of President Yrigoyen, whose high-handed style of governing put him in a precarious situation following the Wall Street Crash of 1929. The regime that deposed the aging Yrigoyen in a coup in September, 1930, gave way to elections the following year, for which the new regime organized the Concordance, a coalition of the National Autonomist Party (the conservative party in power during most of the 1880-1916 era) with centrist Radical Civic Union figures opposed to Yrigoyen and amenable Socialists. Having been part of the latter group since 1927, Noble joined the ticket and was elected to the Chamber of Deputies (lower house of congress). Representing the city of Buenos Aires until 1936, he introduced a number of progressive bills that became law, including needed anti-abuse reforms to rural Argentina's Justice of the Peace system and the landmark Law 11723, the basis for Argentina's Law of Intellectual and Artistic Property.[2]

These accomplishments brought him to the attention of the president of the Chamber of Deputies, Manuel Fresco, who appointed Noble second vice-president of the body. Elected governor of the Province of Buenos Aires in November, 1935, on the Corcordance ticket through fraud, as many Concordance lawmakers were during the "Infamous Decade," Fresco initiated a number of needed housing and highway projects, among other public works. He appointed Noble minister of government, a prominent post which drew ire from Fresco's more conservative colleagues within the party. Noble's encouragement of the governor's relatively progressive social policy (particularly land reform) also convinced many in the Concordance that Fresco had clear presidential ambitions. Forcing Noble to resign his post and Fresco to step aside, the party rigged the 1940 elections in favor of a staunchly reactionary candidate, Alberto Barceló.[3]

This disappointment led Noble to renounce direct political involvement in the future. He turned to the promotion of cultural activities and was appointed head of the National Commission for Culture, a body he helped create during his days in the lower house. Seeking an alternative to Buenos Aires's three principal newsdailies, La Nación, La Prensa and La Razón (all of a decidedly conservative bent), Noble sold and the bulk of his estate (including his prized pampas ranch) for US$1.6 million and, printing an initial distribution of 60,000 copies, he inaugurated Clarín (the "Clarion") on Tuesday, August 28, 1945.[4]

Clarín

"A touch of Argentine attention to Argentine problems," as he billed Clarín, the daily's tabloid format stood out in newsstands from its broadsheet competitors and sold out on its first day in Buenos Aires newsstands. It also stood out for its innovative front page layout. Sporting large headlines, relatively brief introductory text below each, and copious illustrations, the front page served primarily as a table of contents inviting the reader to look inside for more. The iconic title, moreover, was placed to accommodate the layout and could be found anywhere on the top half of the paper's smaller, more manageable front page, giving the daily a whimsical touch. This design, a novelty in 1945, made Clarín more "reader-friendly" than other local dailies and later influenced newspaper front pages around the world, including British tabloids and news dailies such as USA Today.[2]

The attention-catching paper soon developed a loyal contingent of readers, however, because of its professed neutrality. Inaugurated two months before the birth of the Peronist movement, arguably the central political development in Argentina since 1945, Clarín provoked few conflicts with the imposing new President Juan Perón, whose opposition Democratic Union he had endorsed; whereas La Nación and La Prensa personally accused Perón and, particularly, the first lady, Eva Perón (whom La Prensa only referred to as "the wife of the president") of the day's problems, Clarín focused on issues of social and economic development (particularly Argentina's budding industrialization, a concern it shared with the Perón administration), offering articles rich in facts, figures and anecdotes with limited editorials. It also benefited from Perón's hostility towards some competing magazines and dailies, particularly La Prensa, which Perón expropriated in April, 1951 (on the eve of his reelection campaign).[2]

The tireless Noble met Ernestina Herrera while on one of his rare vacations, in 1950. He and the 25-year-old Flamenco dancer, who had little in common, soon developed a relationship. The confirmed bachelor, however, also enjoyed a relationship with Guadalupe Zapata, a Chilean divorcée, whom he married in 1958 (the couple had a girl, Guadalupe, in 1959). The matrimony was an unhappy one, however, leading to their separation a few years later.[5]

Earning renown as both a businessman and journalist, he was awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of Malta in 1951 and Columbia University's prestigious Maria Moors Cabot prize in 1955.[6] Noble, a supporter of developmentalism, endorsed Arturo Frondizi who, during his 1958-62 presidency promulgated the Law of Foreign Investment and other incentives which, together, resulted in sharp increases in energy and industrial production (leading to the elimination of Argentina's stubborn trade deficits of the 1950s). Clarín's support of these measures helped lead to its widespread preference by the Argentine middle class (Latin America's largest, proportionately)[7] and, by 1965, Clarín enjoyed the largest circulation in Argentina, a trend reinforced by innovations such as weekly color supplements and thematic inserts (firsts in the Argentine newspaper industry).[4][8]

Noble resisted the drive towards unionization being felt across Argentina's vast publishing industry during the 1960s, a development primarily a result of publishing workers' union leader Raimundo Ongaro, whose Socialist ideology put him at odds with the paramount CGT labor federation. Interviewed at the time regarding his career, Noble described his own early Socialist affiliations as a "youthful indiscretion."[2] Attempts on the part of Clarín employees to organize were likewise met with swift dismissals, a policy facilitated by Argentina's return to military dictatorship in 1966. Noble had, however, not supported the 1966 coup against the moderate Arturo Illia. Close to President Illia's War Secretary, General Ignacio Ávalos, he supported Ávalos' efforts to persuade Illia to remove the Head of the Armed Forces Joint Chiefs, Juan Carlos Onganía, whom Ávalos suspected of plotting a coup despite the wily Onganía's protestations of loyalty.[9]

His health declining, he established the Noble Foundation in 1966 for charitable purposes and married his longtime companion, Ernestina Herrera in 1967. Roberto Noble died in Buenos Aires two years later, at age 66, and was interred at La Recoleta Cemetery.[10]

References

- ↑ Conapred Archived 2009-02-26 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 4 5 Una rosa de cobre

- ↑ Walter, Richard. The Province of Buenos Aires and Argentine Politics, 1912-1943. Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- 1 2 Funding Universe: Clarín

- ↑ Notícias (in Spanish) Archived 2011-05-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Clarín". Archived from the original on 17 March 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Statistical Abstract of Latin America. UCLA Press.

- ↑ Universidad Nacional de La Matanza blog (in Spanish)

- ↑ Potash, Robert. The Army and Politics in Argentina. Stanford University Press, 1996.

- ↑ Rincones, Historias y Mitos de Buenos Aires (in Spanish)