Roscoe Conkling | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Senator Conkling, c. 1866-68 | |

| United States Senator from New York | |

| In office March 4, 1867 – May 16, 1881 | |

| Preceded by | Ira Harris |

| Succeeded by | Elbridge Lapham |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York | |

| In office March 4, 1859 – March 3, 1863 | |

| Preceded by | Orsamus Matteson |

| Succeeded by | Francis Kernan (redistricting) |

| Constituency | 20th district |

| In office March 4, 1865 – March 3, 1867 | |

| Preceded by | Francis Kernan |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Bailey |

| Constituency | 21st district |

| Mayor of Utica | |

| In office March 9, 1858 – November 19, 1859 | |

| Preceded by | Alrick Hubbell |

| Succeeded by | Charles Wilson |

| Oneida County District Attorney | |

| In office April 22, 1850 – December 31, 1850 | |

| Preceded by | Calvert Comstock |

| Succeeded by | Samuel B. Garvin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 30, 1829 Albany, New York, U.S. |

| Died | April 18, 1888 (aged 58) New York, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Forest Hill Cemetery Utica, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Whig (before 1854) Republican (1854–1888) |

| Spouse | Julia Seymour |

| Parent(s) | Alfred Conkling Eliza Cockburn |

| Relatives | Frederick A. Conkling (brother) Alfred Conkling Coxe Sr. (nephew) |

| Signature |  |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829 – April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican politician who represented New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate.

He is remembered today as the leader of the Republican Stalwart faction and a dominant figure in the United States Senate during the 1870s. As Senator, his control of patronage at the New York Customs House, one of the busiest commercial ports in the world, made him very powerful. His comity with President Ulysses S. Grant and conflict with Presidents Rutherford B. Hayes and James A. Garfield were defining features of American politics of the 1870s and 1880s.[1] He also participated, as a member of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, in the drafting of the landmark Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Conkling publicly led opposition to civil service reform, which he deemed "snivel service reform,"[2] and defended the prerogatives of senators in doling out appointed posts, a lucrative and often corrupt practice. His conflict with President Garfield over appointments eventually led to Conkling's resignation in 1881. He ran for re-election to his seat in an attempt to display his support from the New York political machine and his power, but lost the special election, during which Garfield was assassinated. Though Conkling never returned to elected office, the assassination elevated Chester A. Arthur, a former New York Collector and Conkling ally, to the presidency. Their relationship was destroyed when Arthur pursued civil service reform, out of his sense of duty to the late President Garfield. Conkling remained active in politics and practiced law in New York City until his death in 1888.[3]

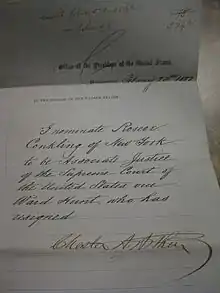

Conkling turned down two presidential appointments to the United States Supreme Court: first to the position of Chief Justice in 1873[1] and then as an associate justice in 1882. In 1882, Conkling was confirmed by the Senate but declined to serve, the last person (as of 2024) to have done so.[3]

Conkling, who was temperate and detested tobacco, was known for his physical condition, maintained through regular exercise and boxing,[1] an unusual devotion for his time.

Early life

Family

Roscoe Conkling was born on October 30, 1829, in Albany, New York to Alfred Conkling, a U.S. Representative and federal judge, and his wife Eliza Cockburn, cousin of the late Lord Chief-Justice Sir Alexander Cockburn of England.[4] His father's ancestors emigrated to the North America around 1635 and settled in Salem, Massachusetts before moving to Suffolk County, New York.[5] Roscoe's maternal grandfather James Cockburn was Scottish by birth, but emigrated to the Bahamas and later to the Mohawk Valley, where he married Margaret Frey, the daughter of a feudal lord.

Roscoe was the youngest of seven children, four sons and three daughters.[6] He had two older brothers, Frederick and Aurelian. A third brother also named Roscoe died before this article's subject was born. Both Roscoes were named for the British author William Roscoe, whom Eliza Conkling read during her pregnancy.[5]

Conkling's mother was said to have a "talent for repartee and brilliant talk" which her son inherited.[7]

Childhood

At the suggestion of William H. Seward, the Conkling family moved to Auburn, New York, via the Erie Canal in 1839. At his new home, Roscoe enjoyed horseback riding, which became a lifelong pursuit. He did not take to academic study, but had a retentive memory.[8]

In 1842, Roscoe was enrolled in the Mount Washington Collegiate Institute in New York City. While in New York, he also studied oratory with his elder brother Frederick. They often practiced their speaking together.[8]

After a year at the Mount Washington Institute, Roscoe entered the Auburn Academy and remained there for three years.[8] Even as a schoolboy, Roscoe's intimidating appearance and intellect demanded attention. A childhood friend said young Roscoe "was as large and massive in his mind as he was in his frame, and accomplished in his studies precisely what he did in his social life — a mastery and command which his companions yielded to him as due."[8]

Conkling first became interested in politics during his time at Auburn. Since his father was a leading member of the upstate Whig Party, Roscoe became acquainted with some of the most prominent men of the era, such as Presidents Martin Van Buren and John Quincy Adams, Governor Enos Throop, Supreme Court Justice Smith Thompson, James Kent, and Thurlow Weed.[8] Fellow Auburn resident William Henry Seward was a friend of Conkling's father and soon of Conkling as well.[9]

Law and local politics

In 1846, seventeen year-old Conkling moved to Utica to study law in the offices of Joshua A. Spencer and Francis Kernan, two of the leading lawyers in the state.[10] He integrated himself into Utica society and spoke publicly on a variety of issues, especially in support of human rights and the abolition of slavery. At eighteen, he spoke at various venues in Central New York in sympathy for the sufferers of the Great Famine in Ireland. He displayed deep abhorrence for slavery, which he described as "man's inhumanity to man," and referred to himself as a "Seward Whig," stumping the county for Taylor and Fillmore in 1848.[11][12]

On one occasion, he is said to have transcribed a Henry Clay speech from memory with such accuracy that Clay himself remarked on its quality. He also practiced his oratory by reciting passages from the Bible, Shakespeare, and British Whigs including Thomas Babington Macaulay, Edmund Burke, and Charles James Fox.[13] In 1849, Conkling gained his first exposure to political campaigning when he was elected as a delegate to his New York State Assembly district's Whig nominating convention, then to the state judicial nominating convention as a supporter Joshua Spencer for the New York Court of Appeals.[12]

Conkling was admitted to the bar in 1850. Almost immediately, Governor Hamilton Fish appointed him as interim District Attorney of Oneida County. He was still only twenty-one, and set about prosecuting cases without the aid of more senior co-counsel. He was nominated for re-election that fall but was defeated along with the rest of the Whig ticket.[14][11] Opposition mainly centered on Conkling's youth.[15]

In 1852, Conkling opened a legal partnership with former Mayor of Utica Thomas R. Walker; the partnership continued until 1855.[16] He became famous throughout central New York after his defense of Sylvester Hadcock for forgery; Joshua Spencer was the prosecutor, but Conkling won acquittal by proving Hadcock's illiteracy.[15] In 1854, he won a case for slander against a priest who had accused a young woman of "want of chastity."[15] In 1855, he partnered with his former classmate Montgomery Throop; their partnership continued until 1862.[17] He became one of the highest-paid attorneys in the region, often charging over $100 per trial.[18]

Through 1853, Conkling remained an orthodox Whig. In 1852, he stumped New York state for General Winfield Scott, denouncing Franklin Pierce as a British tool committed to upholding slavery and free trade to fuel the cotton mills of England.[19] In 1853, Conkling was a leading candidate for Attorney General of New York; he lost the Whig nomination to Ogden Hoffman on the third ballot.[15] As the Whig Party rapidly disintegrated, Conkling took an active part in the formation of the Republican Party and came to consider himself an "original Republican."[20][15] In 1856, he spoke throughout Oneida and Herkimer counties for John C. Frémont and William L. Dayton.[21]

Mayor of Utica (1858–59)

In 1858, Republicans sought a candidate for Mayor of Utica, considered a slightly Democratic city.[22] The party convention nominated Conkling on the first ballot. After a five-day campaign, Conkling defeated Democrat Charles S. Wilson on March 2, 1858, and took office on March 9.[23]

Although he did not run for re-election, Conkling remained mayor until his resignation on November 18, 1859 because the March 1859 election to choose his successor resulted in a tie.[23][24]

U.S. House of Representatives (1859–67)

First term

Almost immediately after his nomination for mayor, Conkling prepared to mount a run for Congress; incumbent Representative Orsamus B. Matteson had chosen to retire after his censure for corruption. Conkling's chief opponent was another Utica attorney, Charles H. Doolittle.[25] Conkling said he hoped to be elected "because some men object to my nomination. So long as one man in the city opposes, I shall run on the Republican ticket." Conkling campaigned as a personal ally of Senator Seward, and Seward delivered a speech on Conkling's behalf.[26] Conkling won easily on the first ballot of the district convention; Doolittle was nominated by future Conkling ally Ward Hunt.[23]

Conkling's opponent in the general election, Judge P. Sheldon Root, had the endorsement of the incumbent Matteson, his former law partner. Root refused to debate Conkling; Conkling stumped the county on his own behalf.[23] Conkling won the election by 2,793 votes out of slightly under 20,000 cast. He ran 200 votes ahead of Governor Edwin D. Morgan.[23]

Conkling's first term as Representative was uneventful. He quietly opposed slavery and his speeches largely consisted of legal expositions.[27] Throughout the protracted battle for Speaker that dominated the first session, Conkling supported John Sherman of Ohio.[28] On the second day of the session, December 6, Conkling allegedly rose and stood to guard Thaddeus Stevens as he castigated Southern Representatives, amid fears that they would assault Stevens.[28] (Representative Preston Brooks had beaten Charles Sumner unconscious only three years prior.) On April 17, 1860, Conkling delivered a long address attacking the Taney Court for its decisions in the Dred Scott case and Ableman v. Booth. Conkling went so far as to reject judicial review as final, arguing "the judgments of the Supreme Court are binding only upon inferior courts and parties litigant."[28]

In the second session of the 36th Congress, Conkling voted in favor of a committee to address the growing secession crisis and gave a speech denouncing secession and slavery. He voted in favor of the Morrill Tariff and against the proposed Corwin Amendment, which would have shielded slavery from federal interference as a step toward reconciliation.[29]

Second term and Civil War

In the summer of 1860, Conkling campaigned on behalf of Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin in New York. Though Conkling was disappointed that Seward had not been nominated, he spoke in favor of Lincoln at a June 4 unity rally.[30] Conkling himself was unanimously re-nominated on September 4 and was re-elected by an increased majority over Utica mayor DeWitt Clinton Grove. As a high-profile House freshman, he spent much more of the 1860 campaign outside his district.[30]

Given his first opportunity to advise President-elect Lincoln on federal appointments in Oneida, Conkling rejected a list provided by district Republicans, replying, "Gentlemen, when I need your assistance in making the appointments in our district, I shall let you know."[29][31]

In 1861, Conkling teamed up with Chester A. Arthur and another man, George W. Chadwick, to make a profit on wartime cotton. The business worked well and was expunged from public record.[32] Conkling later secured Arthur's appointment as a tax commissioner and was later appointed Collector of the Port of New York in 1871.

The 37th Congress met amidst the American Civil War, which began in April 1861. President Lincoln called Congress into a special session on Independence Day in order to equip an army. Conkling took a leading role in the session and was joined in the House by his elder brother Frederick, who had been elected from Manhattan. Conkling was promoted to Chairman of the Committee on the District of Columbia. He introduced a bill to "establish an auxiliary watch for the protection of public and private property in the city of Washington" and another instituting a committee to report on the subject of a general bankruptcy law.[33]

When Congress reconvened on December 3, 1861, Conkling introduced a resolution calling for the War Department to investigate the humiliating Union defeat at the Battle of Ball's Bluff.[34] When George McClellan responded that an investigation would be incompatible with the public service, Conkling delivered a speech calling the battle "the most atrocious military murder ever committed in our history as a people," gaining national attention. His persistent criticism led to the creation of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War to provide civilian oversight of the war effort.[34]

Conkling was a consistent opponent of issuing paper currency to pay for the war effort, unsuccessfully voting against the Legal Tender Act of 1862 and proposing bond issuances redeemable in gold as substitutes. He remained a consistent opponent of monetary expansion throughout his career.[34][35]

Out of office

Conkling was renominated by party faithful at Rome on September 26, 1862.[36] He was opposed by his former law teacher, Democrat Francis Kernan, running on a ticket led by Conkling's brother-in-law, Horatio Seymour, for Governor. Local Democrats quoted criticism of Conkling by radical Representative Elihu Washburne and cited Frederick Conkling's vote against an expansion of the Erie Canal which would have benefitted Roscoe's district. He may also have suffered from the disproportionate enlistment of Republican voters in the Union Army and a growing sentiment opposed to the war in general. Conkling was ultimately narrowly defeated by Kernan by 98 votes, and Seymour was once again elected Governor.[37] Conkling ran behind the Republican gubernatorial candidate, radical James S. Wadsworth, in Oneida.[38]

After leaving office, Conkling returned to Utica and resumed a solo law practice. He continued to give public speeches on occasion, criticizing Governor Seymour.[39] From 1863 to 1865, he acted informally as a judge advocate of the War Department, investigating alleged frauds in the recruiting service in western New York. In the summer of 1863, he and Kernan were opposing counsel in a case regarding an Army deserter.[40]

In 1864, Conkling remained an active supporter of President Lincoln and endorsed his re-nomination and re-election. He rebuffed efforts, including a direct appeal from Horace Greeley, to replace Lincoln on the ticket with a more radical candidate.[41] Conkling was re-nominated on the Union ticket, despite some opposition, on September 22. At the district convention, Ward Hunt produced a letter from Lincoln claiming no other candidate "could be more satisfactory to me" than Conkling. He was nominated by a large vote, but declined. A second vote was taken reaffirming his nomination by acclamation, whereupon he accepted.[42] In the fall election, with a much-improved war effort and political environment for the Lincoln administration, Conkling defeated Kernan to reclaim his seat.

In the time before Conkling returned to the House, President Lincoln was inaugurated, the Civil War came to a close, and Lincoln was assassinated on April 14. Conkling was among the first Union men to arrive in Richmond after its fall, on a fact-finding mission with Charles Dana. He and Seymour also accompanied Lincoln's funeral procession from Albany to Utica.[43]

Third term

Returning to Congress in December 1865, Conkling was appointed to the powerful Committee on Ways and Means, serving alongside future Presidents Rutherford B. Hayes and James A. Garfield. He also served on the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, which drafted the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. He was among the committee's most active supporters of enfranchising freed slaves.

Reconstruction and the Fourteenth Amendment

Within the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, Conkling was a relatively conservative member of the Republican majority, in sympathy with chairman William Pitt Fessenden and in contrast to radicals George S. Boutwell and Jacob Howard.[44]

He subscribed neither to the constitutional theory of secession advanced by the radical Thaddeus Stevens or Charles Sumner, who held that secession (or dissolution of the Southern states) had been achieved, leaving Congress plenary power to govern their territory, or of President Andrew Johnson, which held that secession was impossible and that the Southern states remained in the Union. Instead, Conkling endorsed the theory advanced by Samuel Shellabarger and Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, which held that secession was impossible and void, but that states had lapsed from the guaranteed republican form of government, thus entitling Congress to prescribe the steps for reinstating a proper government.[44]

In order to establish these steps, the Joint Committee began work on the Fourteenth Amendment. Conkling took an active part in drafting the amendment, particularly its provision on representation, Section 2. His draft excluded, for the purpose of apportioning representation, all persons of a race or color whose political or civil rights and privilege were denied, thus punishing the jurisdiction which so denied them.[44] Conkling was also responsible for substituting the word "persons" for "citizens" in Section 2.[44]

Blaine-Fry affair

Conkling's long rivalry with James G. Blaine had its roots in his final term as Representative. In April 1865, in connection with his work for the War Department, Conkling had been selected as a special prosecutor in the case of Major John A. Haddock, who as provost marshal was responsible for administering the draft in western New York and accused of flagrant corruption.[45] Conkling zealously secured a conviction but retained a grudge against Haddock's commanding officer, General James Barnet Fry, whom Conkling believed was truly responsible for the corrupt conduct of Haddock's office.[45] At the opening of the 39th Congress, Conkling introduced a resolution, which passed, to study the potential of eliminating Fry's position of Provost-Marshal General.[45]

In April 1866, a bill to reorganize the army was introduced which would have made Provost-Marshal General a permanent office. On April 24, Conkling rose to strike this section, on the grounds that it "create[d] an unnecessary office for an undeserving public servant. It fastens, as an incubus upon the country, a hateful instrument of war, which deserves no place in a free government in a time of peace."[46] Blaine, who had by then already clashed with Conkling on a number of matters in the House, replied in vehement defense of Fry, though they were not acquainted. In the ensuing debate, both Blaine and Conkling exchanged sharp personal attacks, before Conkling offered to settle the matter "not here but elsewhere." The argument was renewed several times during the week, until April 30, when Blaine read a letter into the record which he had written with General Fry, taking issue with Conkling's statement and making specific charges of graft in connection with Conkling's work for the War Department. After Conkling's rebuttal, the debate culminated in an oft-quoted speech in which Blaine derided Conkling's "haughty disdain, his grandiloquent swell, his majestic, supereminent, overpowering, turkey-gobbler strut," prompting Conkling later to demand an apology that Blaine refused to give.[47]

Though the charges by Fry were investigated and unanimously dismissed by an investigatory committee as having "no foundation in truth" and Conkling's conduct as "above reproach... eminently patriotic and valuable," Conkling never forgave Blaine. Their personal animosities shaped Republican presidential politics for the next two decades and possibly cost Blaine the presidency in 1884 when Conkling, still a power in the closely-fought state of New York, not only refused to help Blaine, but worked for his defeat.[48]

U.S. Senator (1868–81)

1867 election

Conkling was re-elected to the House over Palmer Kellogg in November 1866.[49] Confident of his victory in advance, Conkling spent the fall campaign working on behalf of other Republicans in an effort to actively, privately seek the United States Senate seat of Ira Harris, whose term expired in the coming March. By campaigning throughout the state, he studied the political situation in every county and secured the allegiances of local party leaders. The political organization he formed in his canvas for Senate later formed the basis for the Stalwart faction of the Republican Party.[50]

With Republicans firmly in control of the state legislature, the election would be determined by the Republican caucus, where the field gradually dwindled to Harris, Conkling, and Judge Noah Davis, who was backed by Governor Reuben Fenton and most of western New York.[51] Conkling was endorsed in the caucus by Andrew Dickson White, a signal that his candidacy was backed by George William Curtis, and was nominated on the fifth ballot after the small minority of Harris men chose him over Davis.[51]

Conkling joined the Senate as a member of the Committees on Appropriations, the Judiciary, and Mines and Mining.[52] He became a popular subject of press attention and was even mentioned as a potential candidate for president in 1868.[53]

Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

Conkling was a frequent critic of President Andrew Johnson and supporter of aggressive Reconstruction policies.[54]

In Johnson's impeachment trial for the removal of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, Conkling did not serve as a manager or make any public speech but was active in the prosecution of the case. He voted guilty on several articles before the Senate adjourned. Conkling fell ill while the Senate remained in recess, but declared that if he were unable to walk or speak, he would still be carried to the chamber with the word "Guilty" pinned to his coat.[55]

The Senate fell one vote short of convicting Johnson and removing him from office. Conkling remained Johnson's antagonist for the remainder of the latter's term.[55]

Grant administration

Conkling actively supported the Ulysses S. Grant administration and its policy in Santo Domingo, including the Annexation of Santo Domingo. He became known as the "Warwick of the [Grant] Administration."[56]

During the Franco-Prussian War, Conkling expressed his sympathies with the German side, arguing that Napoleon III's support of the Confederates in the Civil War had made him the enemy of the United States.[57] Nevertheless, Conkling defended the administration from Charles Sumner's charges of violating neutrality by selling arms to France.[58]

In 1870, New York elected its first Democratic legislature since the War. When the new legislature repealed and rescinded its prior resolution ratifying the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Conkling spoke out against it.[59] He actively worked for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, opposing attempts by Senator Allen Thurman to water down its provisions.[60]

In the 43rd United States Congress, Conkling opposed federal relief for the Boston Fire of 1872, efforts to establish a uniform national system of bankruptcy law, and an increase in congressional salaries. He spoke against seating Republican Senator Alexander Caldwell of Kansas, who stood accused of bribery and ultimately resigned.[61] He served on the committees on Foreign Relations, Commerce, and the Judiciary, and chaired the committee on the Revision of Laws.[62]

In 1873, after the death of Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, President Grant urged him to accept an appointment to the seat, but Conkling declined.[63][64] He stated, "I could not take the place, for I would be forever gnawing my chains."[65] Instead, Grant nominated George Henry Williams, who was rejected by the Senate. Conkling declined once more, and Grant appointed Morrison Waite, who was confirmed.[66]

1873 election

After the Democratic victories in the 1870 state elections, Conkling's political future was uncertain. Conkling privately told friends he did not expect re-election. He was offered a $50,000 yearly salary as a law partner in New York City but turned it down.[67] However, after victories in 1871 and 1872, Conkling was re-elected without much competition or fanfare.[68]

Power struggle with Reuben Fenton

.png.webp)

In 1869, upon the retirement of William H. Seward as Secretary of State and the defeat of senior Senator Edwin D. Morgan, Senator Conkling suddenly became the most senior figure in the New York Republican Party. His new junior colleague, former Governor Reuben Fenton, quickly gained President Grant's ear and claimed to have control over presidential appointments in New York.[69] Conkling and Fenton also disagreed over proposed amendments to the Tenure of Office Act of 1867, which had given rise to the controversy over Johnson's removal of Secretary Stanton. Fenton supported repeal of the bill entirely, in line with the position of the New York Legislature.[70]

Fenton's influence with Grant evidently came to an end in 1870, when Grant appointed Conkling's choice for Collector of the Port of New York, Thomas Murphy. Only Fenton, Charles Sumner, and Joseph S. Fowler voted against the appointment as Republicans. After this, Conkling was more influential with the Grant administration than any Senator except Oliver Morton.[71] At the 1870 state convention, Conkling and his allies accused Fenton of a corrupt bargain with Boss Tweed of Tammany Hall for control of the New York City party organization; many of Fenton's supporters held sinecures in city government.[72] The Republicans lost the 1870 election by a wide margin; Conkling blamed the loss on betrayal by the Fenton faction.[73]

In 1871, Conkling gained Grant's support to reform the New York City organization. State chairman Alonzo Cornell removed the "Tammany Republicans" over Fenton's objection and founded a successor organization led by Horace Greeley and Jackson S. Schultz; Greeley declined and joined Fenton's organization instead, precipitating a struggle for power within the city party.[74] The struggle was ended at the 1871 state convention in Syracuse. Hamilton Ward Sr. suggested that each organization be given half the vote of New York County, but Conkling successfully prevented this move, delivering an extemporaneous speech:[75]

A horde of ballot-box pirates and robbers have clutched by the throat the greatest city of the Western world. A horde of pirates, whose firm-name is Tammany Hall… is presenting in its own organization the most hideous spectacle in modern history, has disbanded, tampered with, and to a large part controlled that glorious organization which is the brightest in the annals of political parties…[75]

The delegates voted to seat the Conkling delegation, and the party platform included an endorsement of President Grant and condemnation of "astounding revelations of fraud and corruption in the city of New York."[76] For the next decade, Conkling was the undisputed leader of the New York Republican Party.[77] Fenton eventually left the party entirely in 1872, supporting the new Liberal Republican Party, which nominated Greeley for President in opposition to Grant.[78]

Hayes administration

Conkling and President Rutherford B. Hayes got off to a rocky start after Hayes named William M. Evarts, a New York opponent of Conkling's machine, as Secretary of State. In addition to elevating a Conkling critic, the appointment precluded Conkling's ally Thomas C. Platt from joining the cabinet as Postmaster General on grounds of regional diversity; traditionally, only one cabinet member could come from a state.[79]

In April 1877, Secretary of the Treasury John Sherman appointed a commission to investigate the New York Custom House. The investigation brought to light extensive irregularities in the service, showing that the federal office holders in New York were rather a large army of political workers and that their positions were secured by and dependent upon their faithful service on behalf of New York City politicians.

After Conkling returned from a European vacation, he took an active part in the 1877 New York state campaign. He and Platt were openly critical of the Hayes administration at the state convention, passing a number of resolutions endorsing Grant over the objection of reformer George William Curtis. Conkling gave a lengthy speech denouncing Curtis, Hayes, and reformers and praising Grant.[80]

The Conkling-Hayes conflict peaked in December 1877, when Hayes nominated Theodore Roosevelt Sr. and L. Bradford Prince to replace Chester Arthur and Alonzo Cornell as the Collector and Naval Officer, respectively, of the Port.[81] The appointments were made on the basis of findings of corruption at the Port of New York by a commission of independent, anti-Conkling Republicans. The nominations were rejected by a vote of 25 to 32, with six Republicans voting for and two Democrats voting against.[82] After the vote, a disagreement between Conkling and Senator John Brown Gordon of Georgia nearly resulted in a duel between the two men, but their friends defrayed the situation.[83]

Nevertheless, Hayes suspended Arthur and Cornell's service on July 11, 1878, and appointed Edwin Atkins Merritt and Silas W. Burt during the congressional recess. Both were confirmed when Congress reconvened in February.[84]

1879 election

In January 1879, Conkling was re-nominated by acclamation and re-elected to a third term easily.[85]

Garfield administration and resignation

Shortly after James Garfield's victory in the 1880 election, Conkling consulted with friends on his future. Though he sought to resign over his differences with Garfield, they urged him to remain in office.[86] Garfield solicited his advice on "several subjects relating to the next administration—and especially in reference to New York interests" and invited Conkling to visit him in Mentor, Ohio. Their conversation there, in private with no witnesses, remained the subject of debate long after both men's deaths.[87]

Garfield assembled a cabinet including James Blaine as Secretary of State and Thomas Lemuel James, a New York enemy of Conkling's, as Postmaster General. He refused to appoint Conkling's proposed candidate, Levi P. Morton, for Secretary of the Treasury. Garfield further angered Conkling when he removed Edwin Atkins Merritt as Collector of the Port of New York during his term and appointed Judge William H. Robertson. Historians disagree over whether Garfield did so at Blaine's insistence[88] rather than on his own initiative.[89]

Merritt's removal halfway through his term and Robertson's appointment pressed Conkling to action. He resigned from the Senate May 16, expecting vindication of his own political strength and of the principle of senatorial courtesy by winning the special election to his seat. Thomas C. Platt resigned alongside him.

Conkling's gambit failed: although he attended the legislature's sessions in Albany, Elbridge Lapham was chosen as his successor. Any chance of Conkling's re-election was likely ended, and his political career with it, when President Garfield was shot on July 2 by Charles Guiteau, a fellow Stalwart who had cited the Blaine appointment in threats to the President. Though Garfield was still alive when the election finally concluded on July 22, he died on September 19. Conkling's long-time protégé, Chester Arthur, succeeded to the presidency.

Presidential politics

As a Senator and the boss of the New York Republicans, Conkling was a kingmaker at multiple Republican Conventions. After supporting President Ulysses S. Grant in 1868 and 1872, Conkling ran an unsuccessful campaign of his own in 1876. In 1880, he supported the nomination of Grant for a third term.

Though his preferred candidate was not nominated for president in either case, he was successful in preventing the nomination of an outright reformer. Chester A. Arthur's nomination as vice president in 1880 was designed to appease Conkling (though Arthur accepted over Conkling's objection) and led to Arthur's succession as president after the assassination of James Garfield.

1868 and 1872

Conkling was an active supporter of Ulysses S. Grant's three presidential campaigns. In 1868, he actively campaigned for Grant against his own brother-in-law, Horatio Seymour.[90]

As the 1872 campaign shaped up, Conkling established himself as one of the foremost defenders of the Grant administration. When Charles Sumner introduced a constitutional amendment to limit the presidency to one term in 1871, Conkling spoke against its passage.[91]

Conkling led a barnstorming tour across New York state, beginning in Manhattan on July 23. His speech there was issued, in abridged form, by the state party as a central piece of the Republican campaign in the state.[92] Conkling spoke against Horace Greeley in personal terms, drawing criticism from the Democratic and Liberal Republican press.[93] His next speech was on August 8, after which he hosted a meet-and-greet with President Grant at his mansion in Utica.[94] Grant won the election over Greeley easily, and the Republican ticket swept New York.

1876 campaign

Soon after his re-election to the Senate, Conkling became a leading choice to succeed President Grant. He had the support of Grant and the unanimous backing of the New York Republicans.[95] A public meeting was held in Utica on March 2 to endorse his candidacy,[96] and the Republican state convention on March 22 endorsed Conkling for president.[97] Conkling named as his own second choice Governor Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio,[98] likely to block his rival James G. Blaine from winning the nomination.

At the Republican Convention in Cincinnati on June 14, the New York delegation actively worked to secure Conkling's nomination,[98][lower-alpha 1] and his name was placed forward by Stewart L. Woodford.[100] The other candidates named were Marshall Jewell, Oliver P. Morton, Benjamin Bristow, John Hartranft, Hayes, and Conkling's personal rival James G. Blaine.

After Conkling's vote slipped lower on the first five ballots, a member of the Indiana delegation began a stampede to Hayes, who was nominated. New Yorker William A. Wheeler was nominated for vice president.[101] Conkling pledged to make four speeches on behalf of Hayes, but made only one, claiming ill health.[102]

Conkling played an active part in resolving the disputed election. Acting on the advice of President Grant, he helped write and pass the bill establishing the Electoral Commission of 1877, tasked with resolving the dispute between Hayes and Samuel Tilden. He gave a powerful speech urging its constitutionality, passage as a means of avoiding violence, but declined to serve on the Committee himself.[103] Conkling's own position on the controversy was that neither Tilden nor Hayes should be inaugurated, frequently reported as an implicit endorsement of Tilden.[104]

1880 convention

As the 1880 election approached, a growing movement favored the nomination of President Grant for a third term. Conkling, along with Senators J. Donald Cameron of Pennsylvania and John A. Logan of Illinois, were at its head. At the 1880 state convention, Conkling secured a binding resolution pledging New York's delegates to Grant.[105]

At the national convention, Conkling moved to have all delegates pledge their support to the eventual nominee. After James A. Garfield, a supporter of Senator John Sherman of Ohio for president, delivered a well-received speech against the resolution, Conkling sent him a note which read, "New York requests that Ohio's real candidate and dark horse come forward." Conkling then withdrew his motion.[106]

On the fourth day, Conkling placed Grant's name in nomination, and the nomination was seconded by William O'Connell Bradley.[107] Grant's strongest opponents were Conkling's rivals James G. Blaine and Sherman, who was nominated by Garfield. Conkling marshaled the Grant delegates through dozens of successive ballots, never wavering in his support. On the fifth night, some delegates suggested that Conkling could be nominated if he would withdraw Grant's name; he declined.[108] The non-Grant delegates struggled to find an alternative candidate, but it became clear they would not support Grant under any circumstances.[109]

On the sixth day, Garfield emerged as the consensus anti-Grant choice.[108] He received the necessary majority on the thirty-sixth ballot of the convention, and Conkling moved to make his nomination unanimous.[108][110] The Garfield campaign sought to reconcile with Conkling's Stalwarts by offering one of them the vice presidential nomination.[111] They first approached Levi P. Morton; Conkling was still angry over Grant's loss and advised Morton to decline, which he did.[111] Garfield's supporters then offered the nomination to Chester A. Arthur, who they knew had close ties to Conkling, but who had impressed delegates with his work to broker a compromise on the selection of a permanent chairman at the start of the convention.[108] Conkling tried to talk Arthur out of accepting, urging him to "drop it as you would a red hot shoe from the forge," but Arthur insisted that he would, calling the vice presidency "a greater honor than I ever dreamed of attaining."[111][112] Arthur won the nomination with 468 votes to 193 for Elihu Washburne and 44 for Marshall Jewell.[108]

1880 campaign

During the general election campaign, Conkling conspicuously avoided Garfield, declining the nominee's invitations to meet. When a conference of Republican leaders convened at the Fifth Avenue Hotel to meet with Garfield, Conkling left his seat conspicuously vacant.[113] In response to entreaties from friends, he simply replied, "There are some matters which must be attended to before I can enter the canvass." This remark was widely reprinted in press throughout the North as evidence of Garfield's weak position.

Conkling only began to campaign actively after Grant and Arthur personally prevailed upon him to do so.[114] Conkling gave a well-received speech at New York's Academy of Music, then travelled west to deliver a series of speeches in Ohio alongside President Grant.[115] At the insistence of Grant and Senator Cameron, they stopped at Garfield's home in Mentor. During his entire visit, Conkling refused to be left alone with Garfield.[116] He made four more speeches in Indiana, then returned to New York for the remainder of the campaign.[117]

Positions and views

Conkling was a Radical Republican, favoring equal rights for ex-slaves and reduced rights for ex-Confederates. He was active in framing and pushing the legislation framing Reconstruction, including the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

Conkling defended a proposal ordering the construction of a transcontinental telegraph to the Pacific Ocean.

He also championed the broad interpretation of the ex post facto clause in the Constitution. (See Stogner v. California)

Temperance

Conkling was a moderate on the issue of alcohol. In 1873, Conkling submitted a resolution on behalf of the temperance movement within his district[118] and spoke in support of the movement's aims at the 1873 state convention, but denounced any "irrational effort" to ban alcohol as indefensible.[119]

Monetary policy

While in the House, Conkling notably broke with the Republican Party over the passage of the Legal Tender Act, which established Treasury notes as legal currency in order to better fund the war effort. In this opposition he was joined by his brother, Frederick Augustus Conkling. Both were "hard money" men, arguing that the only legal tender could be precious metals (gold and silver) and that the war could be won without extending the Union's line of credit.[120] Instead, he argued for reducing the costs of government by cutting salaries and limiting congressional travel expenses.[36]

Conkling also vigorously opposed the so-called "inflation bill", which would have authorized an additional $46 million in bank notes. The bill passed, but President Grant vetoed it and a compromise was reached.

He was an active opponent of the Bland-Allison Act and any legislation attempting to increase the supply of silver.[121][122]

Civil rights and Reconstruction

Conkling was a lifelong advocate for civil rights for freed black Americans. He remained an advocate for Southern Reconstruction long past its political popularity in the North and even beyond President Hayes's decision to withdraw federal troops from Southern states.[123]

Women's rights

In 1877, Conkling presented a petition on behalf of citizens of New York, mostly women, calling for an amendment granting all women the right to vote.[104]

Retirement

After resigning from the Senate in 1881, Conkling returned to the practice of law.

As one of the original drafters of the Fourteenth Amendment, he claimed in a case which reached the Supreme Court, Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad, 118 U.S. 394 (1886),[124] that the phrase "nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws" meant the drafters wanted corporations to be included, because they used the word "person" and cited his personal diary from the period. Howard Jay Graham, a Stanford University historian considered the pre-eminent scholar on the Fourteenth Amendment, named this case the "conspiracy theory" and concluded that Conkling probably perjured himself for the benefit of his railroad friends.[125]

Relationship with President Arthur

Conkling and Arthur were so intimately associated that it was feared, after President Garfield was assassinated, that the killing had been done at Conkling's behest in order to install Arthur as president and bring about restoration of the patronage system of political appointments. After Arthur assumed the presidency upon Garfield's death in September 1881, Conkling attempted to sway his protégé into reversing the earlier appointment by Garfield of William H. Robertson as Collector of the Port of New York. Arthur, who would become an avid champion of civil service reform, refused.[126]

On February 24, 1882, Arthur nominated Conkling as an associate justice of the Supreme Court, following the retirement of Ward Hunt.[127] Arthur submitted the nomination to the Senate not knowing whether Conkling would accept it or not.[126][128] He was confirmed by the Senate on March 2, 1882, by a 39–12 vote,[127] but declined to serve in a letter to Arthur citing "reasons you would not fail to appreciate."[126][128]

The breach between Arthur and Conkling was never repaired.[126] Without Conkling's leadership, his Stalwart faction dissolved. However, upon Arthur's death in 1886, he attended the funeral and showed deep sorrow according to onlookers.

Personal life

During his first term as Senator, Conkling purchased a mansion in Utica (3 Rutger Park) that remained his primary residence until his death. He adorned his walls with photos of Lord Byron, Daniel Webster, William W. Eaton, and Antonio López de Santa Anna (presented to Conkling's father during his time as Minister to Mexico).[129]

Conkling was an avid reader of poetry, particularly the works of Lord Byron.[130] He sometimes quoted or recited poetry in his speeches.[131] He made careful study of British oratory throughout his life, and was a particular admirer of Thomas Babington Macaulay.[132]

Conkling was a personal friend and political ally of Senator Blanche Bruce, whom he defended against both racist and reformist critics, and who named his son Roscoe Conkling Bruce in honor of their friendship.[123]

Marriage and romantic affairs

Conkling married Julia Catherine Seymour, sister of Governor of New York Horatio Seymour, on June 28, 1855; Horatio was strongly opposed to the marriage and remained a forceful political opponent of Conkling's. Their marriage was unhappy; Conkling focused on politics and was frequently unfaithful.[133] They became estranged as early as 1863.[134]

Conkling had a reputation as a philanderer, and was accused of having an affair with the married Kate Chase Sprague, daughter of Salmon P. Chase and wife of William Sprague IV. According to a well-known story, buttressed by contemporaneous press reports, Mr. Sprague confronted the philandering couple at the Spragues' Rhode Island summer home and pursued Conkling with a shotgun.[135] One posthumous account from The New York Times (October 12, 1909) stated:

The late Senator Roscoe Conkling was a frequent visitor at Canonchet [Sprague's estate], and was unpleasantly conspicuous in the proceedings which ended in the divorce of the Spragues. Mr. Conkling was once forbidden by Mr. Sprague to come to Canonchet. Despite this, however, the Executive [Sprague] later met the Senator [Conkling] on the estate coming from the rear of the house—some reports had it that the Senator jumped from a window—and after him came the Governor with his old civil war musket in his hands.[136]

Physical fitness

Throughout his life, Conkling was noted for his advocacy of physical culture, a somewhat unorthodox pastime for a man of his era and social status. Conkling maintained his physique through horseback riding and boxing.[132] He took daily walking trips throughout his life.[137]

Stories of his boxing exploits frequently appeared in the press, though their accuracy is questioned.[132] Perhaps due to his massive frame (6'3")[138] and dominant physical presence, Conkling drew frequent press attention.[53] Despite his pride in his physique, Conkling was known to have a peculiar aversion to "having his person touched."[139]

In the summer of 1868, Conkling, Louis Agassiz, Samuel Hooper, and others traveled to the Rocky Mountains, including a visit to Pike's Peak.[90]

In his retirement, he became a governing member of the New York Athletic Club.[137]

Death and legacy

On March 12, 1888, Conkling attempted to walk home three miles from his law office on Wall Street through the Great Blizzard of 1888. Conkling made it as far as Union Square before collapsing. He contracted pneumonia and developed mastoiditis several weeks later which, following a surgical procedure to drain the infection, progressed to meningitis. Conkling died in the early morning hours of April 18, 1888.[140][141] After leaving the Senate, Conkling had reconciled with Mrs. Conkling, and both his wife and daughter were with him when he died. Conkling is buried at Forest Hill Cemetery in Utica.

Legacy

Roscoe Conkling's enduring legacy is scant. Though he was a consequential, colorful and powerful political figure in his day, few lasting social or legislative achievements are attributed to him. Chauncey Depew, the noted railroad executive, political observer and himself a member of the United States Senate from New York from 1899 to 1911, commented thus more than 30 years after Conkling's death: "[Roscoe Conkling] was created by nature for a great career ... he was the handsomest man of his time ... his mental equipment nearly approached genius ... [but] with all his oratorical power and his talent in debate, he made little impression on the country and none upon posterity ... The reason for this was that his wonderful gifts were wholly devoted to partisan discussions and local issues."[142]

A statue of him stands in Madison Square Park in New York City. Conkling is the namesake to the hamlets Roscoe, New York,[143] Roscoe, South Dakota, and Roscoe, Georgia[144] and Roscoe Conkling Park, a 625-acre (253 ha) park in Utica, New York containing a zoo, golf course, and ski area. His house in Utica was made a National Historic Landmark in 1975.

Conkling's stature as a powerful politician—and the interests of others in currying favor with him—led to many babies being named for him. These include Roscoe C. Patterson, Roscoe Conkling Oyer, Roscoe Conkling Simmons, Roscoe Conkling Giles, Roscoe Conkling Bruce,[123] Roscoe C. McCulloch and Roscoe Conkling ("Fatty") Arbuckle.[145] Arbuckle's father, however, despised Conkling and named the boy because he suspected the boy wasn"t his own, and as a nod towards Conkling's reputation as a philanderer.[146]

In popular culture

Conkling was an important character in Rosemary Simpson's 2017 detective novel What the Dead Leave Behind.

To spite his large son, whose delivery he believed hastened his petite wife's death and whose great size implied infidelity, William Goodrich Arbuckle named his child Roscoe Conkling Arbuckle in reference to the politician's numerous extramarital affairs.[147]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Paxson, p. 346.

- ↑ Truesdale, Dorothy S. (October 1940). Rochester Views The Third Term 1880, p. 3. Rochester History. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- 1 2 Paxson, p. 347.

- ↑ "Roscoe Conkling". NNDB. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- 1 2 A.R. Conkling, pp. 2–8.

- ↑ Jordan 1971, p. 4.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 360.

- 1 2 3 4 5 A.R. Conkling, pp. 11–14.

- ↑ Jordan 1971, p. 5.

- ↑ Jordan 1971, p. 6.

- 1 2 A.R. Conkling, pp. 17–21.

- 1 2 Jordan 1971, p. 8.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 363.

- ↑ Henry Scott Wilson, "Distinguished American Lawyers: With Their Struggles and Triumphs in the Forum," (New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1891), p. 190.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jordan 1971, pp. 11–13.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 54.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 28–30.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 47.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 57.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 61.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jordan 1971, pp. 16–19.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 71.

- ↑ Jordan 1971, pp. 17–19.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 80–83.

- ↑ Jordan 1971, pp. 26–28.

- 1 2 3 Jordan 1971, pp. 21–23.

- 1 2 A.R. Conkling, pp. 118–20.

- 1 2 Jordan 1971, pp. 25–27.

- ↑ Jordan 1971, p. 34.

- ↑ Broxmeyer, Jeffrey D. "Roscoe Conkling's Wartime Cotton Speculation." New York History 96, no. 2 (2015): 167-81. Accessed September 9, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/newyorkhist.96.2.167 .

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 135.

- 1 2 3 Jordan 1971, pp. 39–43.

- ↑ Jordan 1971, p. 50.

- 1 2 A.R. Conkling, p. 176.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 185.

- ↑ Jordan 1971, pp. 46–49.

- ↑ Jordan 1971, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 196.

- ↑ Jordan 1971, p. 54.

- ↑ Jordan 1971, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Jordan 1971, p. 58.

- 1 2 3 4 Jordan 1971, pp. 63–65.

- 1 2 3 Jordan 1971, pp. 59–65.

- ↑ Jordan 1971, p. 73.

- ↑ Jordan 1971, p. 80.

- ↑ Muzzey, David Saville James G. Blaine, a Political Idol of Other Days, pp.307-308 (1934).

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 281.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 285–86.

- 1 2 Jordan 1971, pp. 85–89.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 290–91.

- 1 2 A.R. Conkling, pp. 292–95.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 296–99.

- 1 2 A.R. Conkling, pp. 299–301.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 332.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 327.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 426.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 323.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 432–33.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 454–55.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 453–54.

- ↑ Peskin, Allan. "Conkling, Roscoe (1829-1888), politician." American National Biography. February 1, 2000; Accessed September 9, 2020.

- ↑ Roscoe Conkling Legal Dictionary Online

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 461.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 463.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 333.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 449–50.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 317.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 318.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 326.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 329–30.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 331.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 334–35.

- 1 2 A.R. Conkling, pp. 340–43.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 344.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 347.

- ↑ Dunkelman, Mark H. (2015). Patrick Henry Jones: Irish American, Civil War General, and Gilded Age Politician. LSU Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-8071-5967-5. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 529.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 538.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 555.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 556.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 561.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 557.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 574.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 632.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 634–35.

- ↑ David Saville Muzzey, James G. Blaine: A Political Idol of Other Days, pp.189-193, Dodd, Mead & Co., 1934.

- ↑ Theodore Clarke Smith, Life and Letters of James Abram Garfield, Vol.II, pp.1106-1142, Archon Books, 1968.

- 1 2 A.R. Conkling, pp. 308–12.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 348.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 436.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 443.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 444.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 451.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 495.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 498.

- 1 2 A.R. Conkling, p. 499.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 503–04.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 501.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 506–07.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 511.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 518–21.

- 1 2 A.R. Conkling, p. 528.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 586–87.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 592–93.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 596.

- 1 2 3 4 5 kensmind (November 3, 2021). "Four More Years: The Republican Convention of 1880". Potus_Geeks. Presidential History Geeks. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 605.

- ↑ Doyle, Burton T.; Swaney, Homer H. (1881). Lives of James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur. Washington, DC: Rufus H. Darby. p. 36 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 3 Reeves, Thomas C. (1975). Gentleman Boss: The Life of Chester A. Arthur. New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 119–121. ISBN 978-0-394-46095-6.

- ↑ Doenecke, Justus (4 October 2016). "James A. Garfield: Campaigns and Elections". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 612.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 613–14.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 615–17.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 623–24.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 626.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 451–52.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 483–84.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 152.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 496.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 567.

- 1 2 3 A.R. Conkling, p. 583.

- ↑ "San Mateo County v. Southern Pacific R. Co. 116 U.S. 138 (1885)". Retrieved 2016-08-06.

- ↑ Graham, Howard J., The "Conspiracy Theory" of the Fourteenth Amendment, 47 Yale L. J. 371 (1938).

- 1 2 3 4 Mitchell, Robert (February 27, 2022). "The senator who said no to a seat on the Supreme Court — twice". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

- 1 2 McMillion, Barry J. (March 8, 2022). Supreme Court Nominations, 1789 to 2020: Actions by the Senate, the Judiciary Committee, and the President (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

- 1 2 Conkling, Alfred Ronald (1889). Life and Letters of Roscoe Conkling. New York, NY: Charles L. Webster & Company. p. 677.

roscoe conkling decline supreme court.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 306–07.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 A.R. Conkling, p. 37.

- ↑ Jordan 1971, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Jordan 1971, p. 52.

- ↑ Peg A. Lamphier, Kate Chase and William Sprague: Politics and Gender in a Civil War Marriage, University of Nebraska Press, 2003.

- ↑ CANONCHET, SPRAGUE HOME IS BURNED: War Governor in Danger as Place Is Destroyed with Loss Exceeding $1,000,000. PRICELESS RELICS LOST House, Remnant of William Sprague's Vast Fortune, Was Identified with Stirring Events in Nation's Annals. New York Times, Oct. 12, 1909, p. 18

- 1 2 A.R. Conkling, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 310.

- ↑ A.R. Conkling, p. 288.

- ↑ O'Grady, Jim (January 27, 2015). "Bad Idea: The Most Powerful Man in America Walks Home Through the Blizzard of 1888". WNYC News. New York, NY.

- ↑ "Roscoe Conkling Dead". The New York Times. New York, NY. April 18, 1888. p. 1.

- ↑ Chauncey M. Depew, "My Memories Of Eighty Years", Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1923

- ↑ Rockland Sullivan County Historical Society

- ↑ Krakow, Kenneth K. (1975). Georgia Place-Names: Their History and Origins (PDF). Macon, GA: Winship Press. p. 192. ISBN 0-915430-00-2.

- ↑ Melissa Block, Roscoe Conkling, "All Things Considered", National Public Radio, April 18, 2001.

- ↑ Ellis, Chris & Julie (April 10, 2005). The Mammoth Book of Celebrity Murder: Murder played out in the spotlight of maximum publicity. Constable & Robertson. ISBN 978-0786715688.

- ↑ Stevens, Dana (2022). Camera man : Buster Keaton, the dawn of cinema, and the invention of the Twentieth Century (First Atria Books hardcover ed.). New York, NY. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-5011-3419-7. OCLC 1285369307.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Notes

- ↑ George William Curtis was the lone New York delegate to oppose Conkling's nomination; he supported Benjamin Bristow.[99]

Further reading

Biographical

- Burlingame, Sara Lee. "The Making of a Spoilsman: The Life and Career of Roscoe Conkling from 1829 to 1873." PhD dissertation Johns Hopkins U. 1974. 419 pp.

- Conkling, Alfred R. (1889). The Life and Letters of Roscoe Conkling: Orator, Statesman, Advocate. New York : C.L. Webster & Co.

- Chidsey, Donald Barr (1935). The Gentleman from New York: A Life of Roscoe Conkling. Cambridge University Press. p. 438.

- Jordan, David M. (1971). Roscoe Conkling of New York: Voice in the Senate. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801406250.

- Paxson, Frederic Logan (1930). Allen Johnson; Dumas Malone (eds.). Dictionary of American Biography: Conkling, Roscoe. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- United States Congress. "Roscoe Conkling (id: C000681)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

Scholarly topical studies

- Eidson, William G. "Who Were the Stalwarts?" Mid-America 1970 52(4): 235–261. ISSN 0026-2927

- Fry, James Barnet (1893). The Conkling and Blaine-Fry controversy, in 1866. New York, Press of A.G. Sherwood & Co.

- Graham, Howard Jay. "The 'Conspiracy Theory' of the Fourteenth Amendment". The Yale Law Journal. Vol. 47, No. 3. (January, 1938), pp. 371–403.

- Morgan, H. Wayne. From Hayes to McKinley: National Party Politics, 1877-1896 (1969) Archived 2012-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Peskin, Allan. Conkling, Roscoe American National Biography Online, (February 2000), (29 January 2007).

- Peskin, Allan. "Who Were the Stalwarts? Who Were Their Rivals? Republican Factions in the Gilded Age." Political Science Quarterly 1984-1985 99(4): 703–716. ISSN 0032-3195 Fulltext: online in Jstor

- Reeves, Thomas C. "Chester A. Arthur and the Campaign of 1880". Political Science Quarterly. Vol. 84, No. 4. (December, 1969), pp. 628–637.

- Reeves, Thomas C. "Gentleman Boss: The Life of Chester Alan Arthur," (1975) (ISBN 0-394-46095-2).

- Shores, Venila Lovina. The Hayes-Conkling Controversy, 1877-1879 (Smith College Studies in History, Vol. IV, No. 4, July, 1919), Northampton, MA, 1919. in The Spoils System in New York. Edited by James MacGregor Burns and William E. Leuchtenburg. New York: Arno Press, Inc. 1974.

- Swindler, William F. "Roscoe Conkling and the Fourteenth Amendment." Supreme Court Historical Society Yearbook 1983: 46–52. ISSN 0362-5249

Encyclopedias

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- . . 1914.

Primary sources

- A. R. Conkling (editor), The Life and Letters of Roscoe Conkling: Orator, Statesman, Advocate (1889) Archived 2012-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- The Nation, March 2, 1882

- Eaton, Dorman B., The Spoils System and Civil Service Reform in the Custom-House and Post-Office at New York (Publications of the Civil Service Reform Association, No. 3), New York, 1881. In The Spoils System in New York. Edited by James MacGregor Burns and William E. Leuchtenburg. New York: Arno Press, Inc. 1974.

External links

- Mr. Lincoln and New York: Roscoe Conkling Archived 2015-09-25 at the Wayback Machine

- United States Congress. "Roscoe Conkling (id: C000681)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.. Includes Guide to Research Collections where his papers are located.

- Roscoe Conkling at Find a Grave