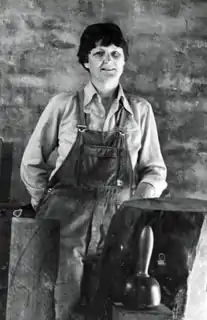

Rosemary Madigan | |

|---|---|

Rosemary Madigan, June 1981 | |

| Born | Rosemary Wynnis Madigan 5 December 1926 |

| Died | 12 February 2019 (aged 92) Australia |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Alma mater | East Sydney Technical College |

| Occupation(s) | sculptor, stonecarver, woodcarver |

| Spouse |

Jack Giles

(m. 1949; div. 1973) |

| Children | 3 |

| Parent |

|

Rosemary Wynnis Madigan (5 December 1926 – 12 February 2019) was an Australian sculptor, stonecarver and woodcarver who focused on the human figure. Born in Glenelg to the geologist Cecil Madigan, she decided on a career as a sculptor at the age of 12 and studied in schools in Adelaide and Sydney. Madigan won a three-year scholarship to study abroad from 1950 to 1953. She began teaching pottery, painting and sculpture at various schools between the 1950s and the 1960s. Madigan was in a working partnership with the constructivist sculptor Robert Klippel until the latter's death in 2001 and won the Wynne Prize for a carved sandstone torso in 1986.

Early life

Madigan was born on 5 December 1926 in Glenelg, South Australia.[1] She was the youngest of five children of the geologist Cecil Madigan.[2] She grew up in the Adelaide suburb of Blackwood and became interested in her father's small collection of Aboriginal artefacts and exhibited a preoccupation with the solid world, wanting to observe objects.[3] Madigan commented on her experience, "It fired a child’s imagination. Why would you want to be a painter when the physicality of such an object was in your midst?"[2] In 1938, she stopped going to school because of illness,[1] and decided to become a sculptor at the age of 12,[4] attending the Girls Central Art School in 1939.[1]

She moved from Adelaide to Sydney during the Second World War in 1940.[2][3][5] Madigan went to night classes in drawing at the East Sydney Technical College (later the National Art School) and was taught by Liz Blaxland.[1][6] She later studied sculpture under Lyndon Dadswell in 1941 to 1942. Madigan returned to Adelaide in 1944 and did a further three years of evening classes at the South Australian School of Art, while gaining employment at an department store.[1][3] She returned to East Sydney in 1947.[1] Madigan went back to the East Sydney Technical College,[3] to complete a diploma in Fine Art under Dadswell's tutelage the following year.[1][2][7]

Career

In 1950, Madigan was awarded the three-year New South Wales Travelling Scholarship by Bob Heffron, the Minister for Education;[8] she was the third sculptor to receive the award.[6][7] She was given the freedom to decide where she would study outside of Australia.[9] Madigan travelled to London to study a diploma in carving at the John Cass College from 1952 to 1953 and acquaint herself with post-war British sculpture.[2][5][6] Much of her time was spent touring Europe and observing the Romanesque sculpture of churches and museums and then India.[6][10] This included a year in Italy,[5] using an automatic drill for the first time in 1952,[11] and spending three weeks drawing the sculptures of the Indian Ellora Caves.[1]

After returning to Adelaide in 1953,[2] Madigan taught pottery, painting and sculpture at multiple schools and the School of Art from the 1950s to the 1960s.[1][6] She completed her first sculpture upon her departure to Australia in Torso in 1954 as part of her desire to understand and articulate the human body.[1] Madigan conceived and designed the St Mark for the Downer fountain at the St. Mark's College, North Adelaide in 1964 and then Yellow Christ and the limewood Eingana that coalesced Aboriginal Australian and European religious and spiritual iconographies four years later.[2] She moved back to Sydney in 1973,[11] and began to teach sculpture at the East Sydney Technical College and at the Sculpture Centre.[1] During this time, Madigan developed an interest in assemblage and collage with a wooden machine before returning to wood carving and stone carving.[2][3]

She began a working partnership with the constructivist sculptor Robert Klippel that lasted until his death in 2001.[4][6] Madigan received grants from the Australia Council between 1976 and 1985,[1] and won the Wynne Prize for a carved sandstone torso in 1986.[3][10] It was the first time for 33 years that a sculptor had won the Wynne Prize.[6] In 1992, Madigan and Klippel's joint work of a major survey was exhibited at Carrick Hill, South Australia,[2][10] and produced a work for display at an exhibition held at the Art Gallery of New South Wales three years later.[6] She moved near to the rural town of Yass, New South Wales in 2001,[3][4] and established a collage and drawing studio and an out of doors space for carving.[3] Madigan continued to work until she was 92 and made her last public appearance at the National Gallery of Australia late in 2018.[2]

Personal life

Deborah Hart, the National Gallery of Australia's head of Australian art, called her "unfailingly adventurous in spirit".[2] She was highly interested in the humanist tradition,[2] had an independent mind,[5][11] and supported the United Kingdom's thought of truth of material.[6] Madigan married her fellow student Jack Giles in 1949 and took on his surname.[1] They had three daughters, one of whom is the harpist Alice Giles, before divorcing in 1973.[2][6] Madigan died on 12 February 2019. She was a grandmother of twelve and a great-grandmother of six.[2] The Art Gallery of New South Wales hold a collection of Madigan's documents, personal papers, files on group and solo editions, press reviews and works.[12]

Analysis

Her works were inspired by the traditions of Asian and European sculptures.[3] Madigan focused mainly on the human torso; according to the Art Gallery of New South Wales, this allowed her to "create sculptures which, at their best, have the sensuousness, subtlety and rigour of the greatest of the Indian carvings she admires."[11] Critical analysis often assessed her work as "a restrained homage to the preoccupations of an earlier generation of modern figurative sculptors" and her most successful works were said to have a quality similar to the artist Henri Gaudier-Brzeska.[1]

Further reading

- Thomas, Daniel (1 February 1992). Schoff, James (ed.). Rosemary Madigan, Robert Klippel at Carrick Hill. Carrick Hill Trust. ISBN 978-0-646-08343-8.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Edwards, Deborah (17 February 2019). "Rosemary Wynnis Madigan b. 5 December 1926". Design and Art Australia Online. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Hart, Deborah (6 March 2019). "Rosemary Madigan: Sculptor with interest in mystical and spiritual traditions". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Mimmocchi, Denise (26 February 2019). "Art Stuff – Vale Rosemary Madigan". Art Gallery of NSW. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- 1 2 3 "Enduring path". Canberra Times. 8 January 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2020 – via Gale OneFile: News.

- 1 2 3 4 "Rosemary Madigan exhibition at The Crisp Galleries". Yass Tribune. 9 December 2010. Retrieved 8 January 2020 – via Gale OneFile: News.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Rosemary Madigan". Bathurst Regional Art Gallery. Archived from the original on 12 March 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- 1 2 Clark, Deborah (1996). Drawn from Life: A National Gallery of Australia Travelling Exhibition. National Gallery of Australia. p. 13. Retrieved 9 January 2020 – via Trove.

- ↑ "Scholarship In Art". The Sydney Morning Herald. 15 April 1950. p. 3. Retrieved 9 January 2020 – via Trove.

- ↑ "S.A. Sculptor To Travel In Strathaird". The Advertiser. 19 July 1950. p. 11. Retrieved 9 January 2020 – via Trove.

- 1 2 3 "Rosemary Wynnis Madigan b.1926". Carrick Hill. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Nelson, Kim (29 October 2010). "Rosemary Madigan – an artist for all seasons". Yass Tribune. Retrieved 8 January 2020 – via Gale OneFile: News.

- ↑ "Papers of Rosemary Madigan [manuscript]: Madigan, Rosemary, 1926–". Register of Australian Archives. 1959. Retrieved 9 January 2020 – via Trove.