The Royal manuscripts are one of the "closed collections" of the British Library (i.e. historic collections to which new material is no longer added), consisting of some 2,000 manuscripts collected by the sovereigns of England in the "Old Royal Library" and given to the British Museum by George II in 1757. They are still catalogued with call numbers using the prefix "Royal" in the style "Royal MS 2. B. V".[1] As a collection, the Royal manuscripts date back to Edward IV, though many earlier manuscripts were added to the collection before it was donated. Though the collection was therefore formed entirely after the invention of printing, luxury illuminated manuscripts continued to be commissioned by royalty in England as elsewhere until well into the 16th century. The collection was expanded under Henry VIII by confiscations in the Dissolution of the Monasteries and after the falls of Henry's ministers Cardinal Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell. Many older manuscripts were presented to monarchs as gifts; perhaps the most important manuscript in the collection, the Codex Alexandrinus, was presented to Charles I in recognition of the diplomatic efforts of his father James I to help the Eastern Orthodox churches under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. The date and means of entry into the collection can only be guessed at in many if not most cases. Now the collection is closed in the sense that no new items have been added to it since it was donated to the nation.

The collection is not to be confused with the Royal Collection of various types of art still owned by the Crown, nor the King's Library of printed books, mostly assembled by George III, and given to the nation by his son George IV, which is also in the British Library, as is the Royal Music Library, a collection mostly of scores and parts both printed (about 4,500 items) and in manuscript (about 1,000), given in 1957.[2]

The Royal manuscripts were deposited in 1707 in Cotton House, Westminster with the Cotton Library, which was already a form of national collection under trustees, available for consultation by scholars and antiquaries; the site is now covered by the Houses of Parliament. The collection escaped relatively lightly in the fire of 1731 at Ashburnham House, to which the collections had been moved. The Cotton Library was one of the founding collections of the British Museum in 1753, and four years later the Royal collection was formally donated to the new institution by the king. It moved to the new British Library when this was established in 1973. The 9,000 printed books that formed the majority of the Old Royal Library were not kept as a distinct collection in the way the manuscripts were, and are dispersed among the library's holdings.

The Royal manuscripts, and those in other British Library collections with royal connections, were the focus of an exhibition at the British Library "Royal Manuscripts: The Genius of Illumination" in 2011–2012.[3]

Highlights

- Codex Alexandrinus, a 5th-century manuscript of the Greek Bible, one of the four Great uncial codices.

- Gospel Book (British Library, MS Royal 1. B. VII), an 8th-century illuminated Insular Gospel Book, closely related to the Lindisfarne Gospels

- Bald's Leechbook, an Old English medical text probably compiled in the 9th century

- Westminster Psalter, from Westminster Abbey, with important miniatures from about 1200 and then 1250

- Rochester Bestiary, 13th century, English

- Matthew Paris, MS Royal 14.C.VII contains his Historia Anglorum (1250–59), 358 x 250 mm, ff 232, also the last volume of the Chronica Majora, and various other items.

- Queen Mary Psalter, a 14th-century English psalter, later owned by Mary I of England

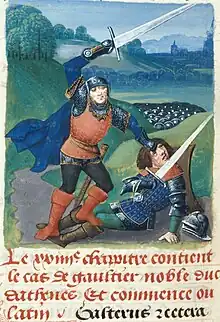

- Talbot Shrewsbury Book a compilation of 15 secular texts in French, made in Rouen, Normandy in 1444/5 and presented by John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury (d. 1453) to the French princess, Margaret of Anjou in honour of her betrothal to Henry VI

- Psalter of Henry VIII, from the 1540s

The Old Royal Library

Before Edward IV

Edward IV is conventionally regarded as the founder of the "old Royal Library" which formed a continuous collection from his reign until its donation to the nation in the 18th century, though this view has been challenged.[4] There are only about twenty surviving manuscripts that probably belonged to the English kings and queens between Edward I and Henry VI,[5] though the number expands considerably when the princes and princesses are included. A few Anglo-Saxon manuscripts owned by royalty have survived after being presented to the church, among them a Gospel Book, Royal 1. B. VII, given to Christ Church, Canterbury by King Athelstan in the 920s, which probably rejoined the collection at the Dissolution of the Monasteries.[6] However these works are scattered among a variety of libraries. By the late Middle Ages luxury manuscripts would generally include the heraldry of the commissioner, especially in the case of royalty, which is an important means of identifying the original owner. There are patchy documentary records which mention many more, though the royal library was from about 1318 covered in the records of the "Chamber", which have survived far less completely than the pipe rolls of the main Exchequer. The careful inventories of the French royal library have no English equivalent until a list compiled at Richmond Palace in 1535.[7]

At the start of Edward III's reign there was a significant library kept in the Privy Wardrobe of the Tower of London, partly built up from confiscations from difficult members of the nobility, which were often later returned. Many books were given away, as diplomatic, political or family gifts, but also (especially if in Latin rather than French) to "clerks" or civil servants of the royal administration, some receiving several at a time, such as Richard de Bury, perhaps England's leading bibliophile at the time as well as an important figure in the government, who received 14 books in 1328. By 1340 there were only 18 books left, although this probably did not include Edward's personal books.[8]

Despite the cultured nature of his court, and his encouragement of English poets, little is known of the royal books under Richard II, although one illuminated manuscript created in Paris for Charles VI of France to present to Richard, the Epistre au roi Richart of Philippe de Mézières (Royal 20. B. VI), was at Richmond in 1535, and is in the British Library Royal manuscripts.[9] The reign of Henry IV has left records of the building of a novum studium ("new study") at Eltham Palace finely decorated with more than 78 square feet of stained glass, at a cost of £13, and a prosecution involving nine missing royal books, including bibles in Latin and English, valued respectively at £10 and £5, the high figures suggesting they were illuminated.[10] The wills of Henry's son, Henry V refer to a Biblia Magna ("Big" or "Great Bible"), which had belonged to Henry IV and was to be left to the nuns of Henry V's foundation at Syon. This may be Royal MS 1. E. IX, with fine historiated initials illuminated in London by several artists from the school of Herman Scheerre of Cologne.[11] A considerable number of religious texts were left to family members, staff and his many chaplains.[12]

Two of Henry V's younger brothers were notable collectors. Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (1390-1447), who had commissioned translations from Greek into Latin and gave most of his collection, 281 books, to the library at Oxford University, where the Bodleian Library later grew around Duke Humfrey's Library. At his death his remaining books mostly went to his nephew Henry VI's new King's College, Cambridge, but some illuminated books in French were kept for the royal library, and are still in the Royal manuscripts. John, Duke of Bedford took over as English commander in France after Henry V's death in 1422, and commissioned two important manuscripts which have reached the British Library by other routes, the Parisian Bedford Hours (Ms Add 18850, in fact presented to Henry VI in 1431) and the English Bedford Psalter and Hours (BL Ms Add 42131). He also used the dominant English position in France to buy the French royal library of the Louvre, from which a few examples remain in the Royal manuscripts.[13]

Edward IV to Henry VII

About fifty of the Royal manuscripts were acquired by Edward IV (1442-1483), a far larger and more coherent group than survive from any of his predecessors. He was not a scholarly man, and had to fight his way to the throne after inheriting the Yorkist claim to the throne at the age of eighteen after his father and elder brother died in battle. He reigned from 1461 until 1470, when machinations among the leading nobles forced a six-month period of exile in Burgundy. He stayed for some of this period in Bruges at the house of Louis de Gruuthuse, a leading nobleman in the intimate circle of Philip the Good, who had died three years before. Philip had the largest and finest library of illuminated manuscripts in Europe, with perhaps 600, and Gruuthuse was one of several Burgundian nobles who had begun to collect seriously in emulation. In 1470 his library (much of it now in Paris) was in its early stages, but must already have been very impressive for Edward. The Flemish illuminating workshops had by this date clearly overtaken those of Paris to become the leading centre in northern Europe, and English illumination had probably come to seem somewhat provincial. The Burgundian collectors were especially attracted to secular works, often with a military or chivalric flavour, that were illustrated with a lavishness rarely found in earlier manuscripts on such subjects. As well as generous numbers of miniatures, the borders were decorated in increasingly inventive and elaborate fashion, with much use of the heraldry of the commissioner.[14]

Many of Edward's manuscripts reflected this taste; like that of Philip, his court displayed an increase in ceremonial formality, and interest in chivalry. Most of his books are large-format popular works in French, with several modern and ancient histories, and authors such as Boccaccio, Christine de Pisan and Alain Chartier. They are too large to hold comfortably, and may have been read aloud from lecterns, though the large miniatures were certainly intended to be appreciated. The largest purchases were probably made from about April 1479, when a part-payment is recorded to a foreign ("stranger") "merchant" or dealer for £80 to "merchant stranger Philip Maisertuell in partie of paiement of £240 of certaine bokes by the said Philip to be provided to the kyngs use in the parties beyond the see." This was perhaps Philippe de Mazerolles, a leading illuminator who had moved from France to Flanders. At least six of Edward's Flemish books are dated to 1479 and 1480; such large books naturally took a considerable time to produce. Further payments totalling £10 are recorded in 1480 for binding eight books, for which other payments record the transport to Eltham in special pine chests.[15] Other manuscripts are no longer in the Royal collection, such as the "Soane Josephus" (MS 1, Sir John Soane's Museum), which remained in the collection until after an inventory in 1666.[16] One of the most splendid books made for Edward in Bruges in the 1470s is a Bible historiale in French in three volumes (Royal MS 15 D i, 18 D ix-x), which was probably begun for another patron, then completed for Edward.[17]

Edward's reign saw the beginning of printing, both in English in 1473-75 and in England itself from 1476, when William Caxton set up a press in Westminster. At the top end of the market the illuminated manuscript continued to retain a superior prestige for many decades. When Edward's brother in law, Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers had Caxton print his own translation of the Dictes and Sayings of the Philosophers in 1477, the book he presented to Edward was a special manuscript copied from the printed edition, with a presentation miniature, implying "that a printed book might not yet have been regarded as sufficiently distinguished for a formal gift of this kind".[18]

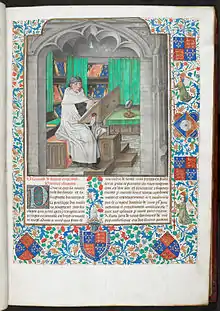

Henry VII appears to have commissioned relatively few manuscripts, preferring French luxury printed editions (his exile had been spent in France). He also added his own arms to a number of earlier manuscripts, a common practice for those bought second-hand. One manuscript, Royal 19. C. VIII, was scribed at Sheen Palace in 1496 by the Flemish royal librarian, Quentin Poulet and then sent to Bruges to be illuminated, and another, Royal 16. F. II, appears to have been begun as a present for Edward IV, then left aside until completed with new miniatures and Tudor roses in about 1490, as a present for Henry.[19]

Henry VIII to Elizabeth

By the time Henry VIII came to the throne in 1509, the printed book had become the norm, though the richest buyers, like Henry, could often order copies printed on vellum. But some manuscripts were still commissioned and illuminated, and Henry and his minister Cardinal Wolsey were the main English patrons in the 1520s. Henry retained a scribe with the title "writer of the king's books", from 1530 employing the Fleming Pieter Meghen (1466/67 1540), who had earlier been used by Erasmus and Wolsey.[20] Although some Flemish illuminators were active in England, notably Lucas Horenbout (as well as his father Gerard and sister Susanna), it seems that more often the miniatures and painted decoration were done in Flanders or France, even if the text had been written in England. Meghen and Gerard Horenbout both worked on a Latin New Testament, mixing the gospels in the Vulgate with translations by Erasmus of Acts and the Apocalypse, which has the heraldry of Henry and Catherine of Aragon (Hatfield House MS 324).[21] Henry also retained a librarian, paid £10 a year in both 1509 and 1534, who in both years was based at Richmond Palace west of London, which seems to have been the location of the main collection.[22] As well as more common northern European manuscripts, Henry also received Italian manuscripts illuminated in full-blown Renaissance style as gifts; at least three remain in the British Library.[23]

It was at Richmond that in 1535 a French visitor compiled the first surviving approach to a list of books in the royal library, though this was only covered the books there, and perhaps was not complete. He listed 143 books, which were nearly all in French, and included many of Edward IV's collection.[24] This was just before Henry's Dissolution of the Monasteries, which was to greatly increase the size of the royal library. In 1533, before the dissolution began, Henry had commissioned John Leland to examine the libraries of religious houses in England. Leland was a young Renaissance humanist whose patrons included Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell and was a chaplain to the king with church benefices, by papal dispensation as he was not yet even a subdeacon. He spent much of the following years touring the country compiling lists of the most significant manuscripts, from 1536 being overtaken by the process of dissolution, as he complained in a famous letter to Cromwell. A large but unknown number of books were taken for the royal library, others were taken by the expelled monastics or private collectors, but many were simply left in the abandoned buildings; at St Augustine's, Canterbury there were still some remaining in the 17th century. Those preserved were often not the ones that modern interests would have preferred.[25]

The monastic books were initially collected in libraries at the palaces of Westminster (later known as Whitehall), Hampton Court and Greenwich, though from around 1549 they were apparently all concentrated at Westminster. There is an inventory from April 1542 listing 910 books at Westminster, and there are press-marks on many books relating to this.[26] It is often impossible to trace the origin of monastic manuscripts in or passing through the royal library - a large number of the books initially acquired were later dispersed to a new breed of antiquarian collectors. The priory of Rochester Cathedral was the source of manuscripts including the Rochester Bestiary, famous for its lively illustrations, and an unillustrated 11th-century manuscript of the Liber Scintillarum (Royal 7. C. iv) with interlinear Old English glosses.

Very probably a good number of medieval liturgical manuscripts were destroyed for religious reasons under Edward VI. The librarian from 1549 was Bartholomew Traheron, an evangelical Protestant recommended by John Cheke.[27] In January 1550 a letter was sent out from the Council instructing the country to "cull out all superstitious books, as missals, legends, and such like, and to deliver the garniture of the books, being either gold or silver, to Sir Anthony Aucher" (d. 1558, one of Henry's commissioners for the Dissolution in Kent). Despite the additions from the dissolved monasteries, the collection that survived is very short of medieval liturgical manuscripts, and a high proportion of those that do remain can be shown to have arrived under Mary I or the Stuarts. There are no illuminated missals at all, only eight other liturgical manuscripts, eighteen illuminated psalters and eight books of hours.[28] Edward died at the age of 16, and was a solitary and studious boy, several of whose personal books are in the British Library. He seems to have centralized most of the library at Whitehall Palace, though Richmond still seems to have retained a collection to judge by the reports of later visitors.[29] The significant addition to the library of Edward's reign, though only completed after his death, was the purchase from his widow of the manuscripts belonging to the reformer Martin Bucer, who had died in England.

Mary I, who restored Catholicism, may have felt the lack of liturgical books, and was presented with at least two illuminated psalters, one the highly important English Queen Mary Psalter of 1310-1320 (Royal 2 B VII), confiscated from Henry Manners, 2nd Earl of Rutland after his arrest. This has in total over 1,000 illustrations, many in the English tinted drawing style. Another, Royal 2 B III, is a 13th-century production of Bruges, which was given by "your humbull and poore orytur Rafe, Pryne, grocer of Loundon, wushynge your gras prosperus helthe", as an inscription says.[30]

Stuarts

The son of James I, Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales (1594-1612), made a significant addition to the library by acquiring the library of John, Lord Lumley (c.1533-1609). Lumley had married the scholar and author Jane Lumley, who inherited the library of her father, Henry FitzAlan, 19th Earl of Arundel (1512-1580), which was among the most important private libraries of the period, with around 3,000 volumes, including much of the library of Archbishop Cranmer. A catalogue survives, a 1609 copy of an original of 1596 that is now lost; Lumley had also given many volumes to the universities in his last years. Soon after Prince Henry's death, the main royal library was moved to St James's Palace where his books had been kept.[31] The Lumley library included MS Royal 14. C. vii, with the Historia Anglorum and Chronica Maiora of Matthew Paris, which had passed from St Albans Abbey to Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester and later Arundel.[32] James I purchased much of the library of the classical scholar Isaac Casaubon who died in London in 1614, and was given the Codex Alexandinus, as explained above.

The royal library managed to survive relatively unscathed during the English Civil War and Commonwealth, partly because the well-known and aggressive figures on the Parliamentarian side of the preacher Hugh Peters (later executed as a regicide) and the lawyer and M.P. Sir Bulstrode Whitelocke were successively appointed as librarians by Parliament, and defended their charge. Whitelocke wanted the library turned into a national library accessible to all scholars, an idea already proposed by John Dee to Elizabeth I, and thereafter by Richard Bentley, the famous textual scholar who became librarian in 1693. There was a new inventory in 1666. The major purchase in the reign of Charles II was of 311 volumes in about 1678 from the collection of John Theyer, including the Westminster Psalter (Royal 2. A. xxii), a psalter of about 1200 from Westminster Abbey to which five tinted drawings were added some fifty years later, including the kneeling knight illustrated above.[33]

Notes

- ↑ Record for Royal MS 2 B V, Manuscripts: Closed collections, British Library

- ↑ Royal Music Library, British Library

- ↑ Genius

- ↑ Stratford, 255, and 266 where she suggests Henry IV and Henry V as alternatives; Backhouse, 267 regards Edward IV as "clearly identifiable as the founder of the Old Royal Library".

- ↑ Stratford, 256

- ↑ Brown, 52, 87

- ↑ Stratford, 255-256

- ↑ Stratford, 258-259

- ↑ Stratford, 260

- ↑ Stratford, 260-261

- ↑ See:

- "Detailed record of Royal MS 1 E IX". British Library. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- Scott, Kathleen L. (1996), Later Gothic Manuscripts 1390-1490, A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in the British Isles, vol. 6, Harvey Miller, ISBN 0905203046

- Given-Wilson, Chris (2016), Henry IV, The Yale English Monarchs Series, Yale University Press, p. 388, ISBN 978-0300154191

- ↑ Stratford, 263

- ↑ Stratford, 266

- ↑ Backhouse, 267-268; Kren & McKendrick, 68-71 and generally

- ↑ Backhouse, 269

- ↑ Kren & McKendrick, 292-294

- ↑ Kren & McKendrick, 297-303

- ↑ Backhouse, 269

- ↑ Kren & McKendrick, 403; 398-400

- ↑ Kren & McKendrick, 520

- ↑ Alexander, 47-49

- ↑ Carley (1999), 274; Doyle, 70-73

- ↑ Alexander, 55

- ↑ Carley (1999), 274; Doyle, 71-72

- ↑ Carley (2002), 341-342, 346-347; Carley (1999), 274-275

- ↑ Carley (1999), 275-276

- ↑ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ↑ Doyle, 73-75

- ↑ Doyle, 73-75

- ↑ Doyle, 75, and catalogue entries 82 and 85

- ↑ Selwyn, 51-52

- ↑ Chivalry, 390

- ↑ Chivalry, 200; BL catalogue Westminster Psalter, who give a later date for the main MS.

See also

References

- Alexander, J.J.G., Foreign illuminators and illuminated manuscripts, Chapter 2 in Hellinga and Trapp.

- Backhouse, Janet, The Royal Library from Edward IV to Henry VII, Chapter 12 in Hellinga and Trapp. google books

- Brown, Michelle P., Manuscripts from the Anglo-Saxon Age, 2007, British Library, ISBN 978-0-7123-0680-5

- Carley, James P., ed., The libraries of King Henry VIII, British Library/British Academy (2000)

- "Carley (1999)", Carley, James P., The Royal Library under Henry VIII, Chapter 13 in Hellinga and Trapp.

- "Carley (2002)", Carley, James P., "Monastic collections and their dispersal", in John Barnard, Donald Francis McKenzie, eds., The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain: 1557-1695 (Volume 4), 2002, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-66182-X, 9780521661829

- "Chivalry": Jonathan Alexander & Paul Binski (eds), Age of Chivalry, Art in Plantagenet England, 1200-1400, Royal Academy/Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1987

- Doyle, Kathleen, "The Old Royal Library: 'A greate many noble manuscripts yet remaining'", in McKendrick, Lowden and Doyle, below.

- "Genius": British Library Press Release for the exhibition "Royal Manuscripts: The Genius of Illumination" 11 November 2011- 13 March 2012

- Hellinga, Lotte, and Trapp, J. B., eds., The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, Volume 3; 1400-1557, 1999, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-57346-7, ISBN 978-0-521-57346-7

- Kren, T. & McKendrick, S. (eds), Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, Getty Museum/Royal Academy of Arts, 2003, ISBN 1-903973-28-7

- McKendrick, Scott, Lowden, John and Doyle, Kathleen, (eds), Royal Manuscripts, The Genius of Illumination, 2011, British Library, 9780712358156

- Selwyn, David, in Thomas Cranmer: churchman and scholar, Paul Ayris & David Selwyn (eds), Boydell & Brewer Ltd, 1999, ISBN 0-85115-740-8, ISBN 978-0-85115-740-5

- Stratford, Jenny, The early royal collections and the Royal Library to 1461, Chapter 11 in Hellinga and Trapp

Further reading

- Birrell, T.A., English Monarchs and their Books: From Henry VII to Charles II, 1987, British Library

- Carley, James P., The Books of King Henry VIII and His Wives, 2004, British Library

- Doyle, Kathleen; McKendrick, Scot, (eds), 1000 Years of Royal Books and Manuscripts, 2014, British Library Publications, ISBN 9780712357081

- George F. Warner and Julius P. Gilson, Catalogue of Western Manuscripts in the Old Royal and King's Collections, 4 vols, 1921, British Museum - source (?) of the British Library online catalogue entries.

External links

- Royal Manuscripts (c 1100-c 1800) finding aid (includes pdf for download)

- Royal Manuscripts: The Genius of Illumination exhibition at the British Library from November 2011

- British Library "typepad" Medieval and earlier manuscripts blog - several entries on individual manuscripts relating to the 2011 exhibition, with excerpts from the catalogue