| Richmond Palace | |

|---|---|

Richmond Palace, west front, drawn by Antony Wyngaerde, dated 1562 | |

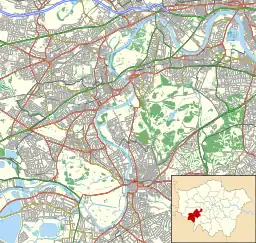

Shown in Richmond upon Thames | |

| General information | |

| Coordinates | 51°27′40″N 0°18′32″W / 51.46117°N 0.30888°W |

| Destroyed | 1649–1659 |

Richmond Palace was a royal residence on the River Thames in England which stood in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Situated in what was then rural Surrey, it lay upstream and on the opposite bank from the Palace of Westminster, which was located nine miles (14 km) to the north-east. It was erected in about 1501 by Henry VII of England, formerly known as the Earl of Richmond, in honour of which the manor of Sheen had recently been renamed "Richmond". Richmond Palace therefore replaced Shene Palace, the latter palace being itself built on the site of an earlier manor house which had been appropriated by Edward I in 1299 and which was subsequently used by his next three direct descendants before it fell into disrepair.

In 1500, a year before the construction of the new Richmond Palace began, the name of the town of Sheen, which had grown up around the royal manor, was changed to "Richmond" by command of Henry VII.[1] However, both names, Sheen and Richmond, continue to be used, not without scope for confusion. Curiously, today's districts of East Sheen and North Sheen, now under the administrative control of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, were never in ancient times within the manor of Sheen, but were rather developed during the 19th and 20th centuries in parts of the adjoining manor and parish of Mortlake. Richmond remained part of the County of Surrey until the mid-1960s, when it was absorbed by the expansion of Greater London.

Richmond Palace was a favourite home of Queen Elizabeth I, who died there in 1603. It remained a residence of the kings and queens of England until the death of Charles I of England in 1649. Within months of his execution, the Palace was surveyed by order of the Parliament of England and was sold for £13,000. Over the following ten years it was largely demolished, the stones and timbers being re-used as building materials elsewhere. Only vestigial traces now survive, notably the Gate House.[2] (51°27'41"N 0°18'33"W). The site of the former palace is the area between Richmond Green and the River Thames, and some local street names provide clues to existence of the former Palace, including Old Palace Lane and Old Palace Yard.

History

Norman

Henry I divided the manor of Shene from the royal manor of Kingston and granted it to a Norman knight.[3] The manor-house of Sheen was established by at least 1125.

1299 to 1495

In 1299 Edward I took his whole court to the manor-house at Sheen, close by the river side. In 1305, he received at Sheen the Commissioners from Scotland to arrange the Scottish civil government.[4]

The house returned to royal hands in the reign of Edward II and after his deposition it was held by his wife, Queen Isabella. When the boy-king Edward III came to the throne in 1327, he gave the manor to his mother Isabella. After her death he extended and embellished the manor house and turned it into the first Shene Palace. Edward III died at Shene on 21 June 1377.[3] In 1368 Geoffrey Chaucer served as a yeoman at Sheen.

Richard II was the first English king to make Sheen his main residence in 1383. He took his bride Anne of Bohemia there. Twelve years later Richard was so distraught at the death of Anne at the age of 28, that he, according to Holinshed, "caused it [the manor] to be thrown down and defaced; whereas the former kings of this land, being wearied of the citie, used customarily thither to resort as to a place of pleasure, and serving highly to their recreation." For almost 20 years it lay in ruins until Henry V undertook rebuilding work in 1414.[3] The first, pre-Tudor, version of the palace was known as Sheen Palace. It was positioned roughly at 51°27′37″N 0°18′37″W / 51.460388°N 0.310219°W, in what is now the garden of Trumpeters' House, between Richmond Green and the River. In 1414 Henry V also founded a Carthusian monastery there known as Sheen Priory, adjacent on the N. to the royal residence.

Henry VI continued the rebuilding in order that the palace might be worthy of the reception of his queen, Margaret of Anjou. Edward IV granted it to his queen Elizabeth Woodville for life.[4]

Tudor

Henry VII, builder of Richmond Palace

In 1492, a great tournament was held at the Palace by Henry VII.[1] On 23 December 1497 a fire destroyed most of the wooden buildings. Henry rebuilt it and named the new palace "Richmond" Palace after his title of Earl of Richmond. The earldom was seated at Richmond Castle, Yorkshire, from which it took its name. In 1502, the new palace witnessed the betrothal of Princess Margaret, daughter of Henry VII, to King James IV of Scotland. From this line eventually came the House of Stuart. In 1509 Henry VII died at Richmond Palace.

The fire of 1497

At Christmastide in 1497, a great fire broke out in the king's private chambers, destroying a large portion of the palace. The Milanese ambassador, Raimondo Soncino, witnessed the blaze, and estimated the damage at 60,000 ducats, in modern money about $10 million or £7 million. The fire lasted three hours and tore through the rest of the palace, causing hundreds to flee in panic.[5] Hammerbeam roofs of the Middle Ages were a structural necessity as much as they were pretty architecture, as they kept the heavy timbered roofs from caving in; they were the carpenter's equivalent of the stone vaulting found in Gothic cathedrals of the Middle Ages because, as in famous examples like Westminster Hall, they let the architect achieve higher heights with thinner walls, and evenly distributed the lateral weight.[6] In as large a fire as described by Soncino the English oak beams of the great hall, a centrepiece of a royal Christmas, would have stood no chance of remaining upright and intact. They would have been engulfed in flames at a temperature of over 270 °C (518 °F). Much of the tapestry work of earlier ages was burnt to cinders, and losses included crown jewels and much of the royal wardrobe, including a large amount of cloth of gold, at this time a luxury item only wearable by royalty; and in the case of Sheen Palace it was a feature of the bedding.[7]

Accounts refer to Henry VII, his mother, Margaret Beaufort, and his wife, Queen Elizabeth, running for their lives, with the king barely making it out in time: one of the corridors nearly collapsed on top of him. As it was the time of the Christmas revels, also present during the disaster were all but one of the royal children, and all under the age of 10: Margaret, Mary, and a six-year-old Henry VIII, each of them described as being hurried out in the arms of their nursemaids. For Queen Elizabeth, this would have been a horrible blow: records show that as a child in the 1470s this was where she spent much of her childhood; the palace would also have had strong associations with her mother Elizabeth Woodville: Edward IV left Sheen to his wife in his will. Soncino reports all of the events outlined above, and also states in his accounts that the king "does not attach much importance to this loss. He purposes to build the chapel all in stone, and much finer than before."[8]

The new Richmond Palace

Construction of the new palace began in 1498. Henry named his creation Richmond Palace, in honour of the title he had held before acceding to the throne which he had inherited from his father: Earl of Richmond. Though the palace did not survive the English Civil War, fragments of the edifice still remain along the bank of the Thames, as does Richmond Park, originally a royal hunting reserve that Henry Tudor and all members of the Tudors and early Stuarts used for their personal entertainment. Henry Tudor built a large and grand palace that became the centre of royal life for many years to come, a very important centre of the court of each Tudor monarch and also James I. Drawings and descriptions of the palace survive, as does the documentation of a 1970s excavation of the grounds; thus posterity has a fairly accurate idea of the contents and features of the building.

Richmond Palace was largely a building of brick and white stone in the latest styles of the times, with geometric octagonal towers, pepper-pot chimney caps, and ornate weather vanes made of brass.[9] Though it retained the layout of Sheen Palace, it had new additions that would mark the Renaissance: for example, long galleries to display sculpture and portraiture. Henry VII also established a library and a richly appointed chapel.[10] The windows were panelled, built to bring in more light than the tiny slit-like windows of a castle, built for defence. From its earliest it had inner courtyards designed for leisure, with several portions built for the royal family overlooking a large green. Richmond Palace covered 10 acres (4 ha) of land and was large and well appointed enough to have its own orchards and walled gardens. It is known that Henry Tudor decorated his home with many gifts he accepted from Italian bankers in Venice, and the evidence for this and the other accoutrements survives in a 17th-century inventory taken of the palace that is now held in the National Archives. The inventory also describes new tapestries he commissioned to replace the ones lost in the fire.

Henry VIII

Later the same year, Henry VIII celebrated Christmas to Twelfth Night at Richmond with the first of his six wives, Catherine of Aragon. During those celebrations, says Mrs. A. T. Thomson, in her Memoirs of the Court of Henry the Eighth:

On the night of the Epiphany (1510), a pageant was introduced into the hall at Richmond, representing a hill studded with gold and precious stones, and having on its summit a tree of gold, from which hung roses and pomegranates. From the declivity of the hill descended a lady richly attired, who, with the gentlemen, or, as they were then called, children of honour, danced a morris before the king. On another occasion, in the presence of the court, an artificial forest was drawn in by a lion and an antelope, the hides of which were richly embroidered with golden ornaments; the animals were harnessed with chains of gold, and on each sat a fair damsel in gay apparel. In the midst of the forest, which was thus introduced, appeared a gilded tower, at the end of which stood a youth, holding in his hands a garland of roses, as the prize of valour in a tournament which succeeded the pageant!"

Henry's son, Henry, Duke of Cornwall, was born there on New Year's Day, 1511, but died on 22 February. Some years later, the king received a present of Hampton Court from Wolsey, and in return the cardinal received permission to reside at the royal manor of Richmond, where he kept up so much state as to increase the growing ill-feeling against him. When he fell into disfavour he took up his residence at the Lodge in the 'great' park, and subsequently moved to the Priory.[4]

In 1533 Richmond became the principal residence of Henry's daughter Mary after she was evicted from her previous residence of Beaulieu. Mary stayed at the palace until December of that year when she was ordered to Hatfield House to wait on the newly born Princess Elizabeth.

In 1540 Henry gave the palace to his fourth wife, Anne of Cleves, as part of her annulment settlement.

Mary I

In 1554 Queen Mary I married Philip II of Spain. Forty-five years after her mother Catherine of Aragon had spent Christmas at Richmond Palace, they spent their honeymoon there (and at Hampton Court). Later that same year, her sister Elizabeth I was taken to Richmond as a prisoner on her way to Woodstock.

Elizabeth I

Once Elizabeth I became queen she spent much of her time at Richmond, as she enjoyed hunting stags in the "Newe Parke of Richmonde" (now the Old Deer Park). Elizabeth I died there on 24 March 1603.

Stuart

James I

King James I preferred the Palace of Westminster to Richmond, but his eldest son Prince Henry was able to commission water-works for the garden designed by the French Huguenot, Salomon de Caus, and the Florentine Costantino de' Servi, shortly before his death in 1612.[11] Before he became king, Charles I owned Richmond Palace and started to build his art collection whilst living there. Like Elizabeth I, Charles I enjoyed hunting stags, and in 1637 created a new area for this now known as Richmond Park, renaming Elizabeth's "Newe Parke" the "Old Deer Park". There continue to be red deer in Richmond Park today, possibly descendants of the original herd, free from hunting and relatively tame.

Charles I, the Commonwealth and demolition

Charles I gave the palace with the manor to Queen Henrietta Maria, probably in 1626, and it became the home of the royal children. Within months of the execution of the king in 1649, Richmond Palace was surveyed by order of Parliament to see what it could fetch in terms of raw materials, and was sold for £13,000. Over the next ten years it was largely demolished, the stones being re-used as building materials.

Restoration of the monarchy

Following the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, the Palace and manor were restored to Queen Henrietta Maria (d.1669), the mother of Charles II of England and widow of the beheaded King Charles I, who during the Civil War had lived in exile in France. It was then in a dismantled condition, having suffered much dilapidation during the inter-regnum. The ruined palace was never rebuilt.

Architecture and internal decoration

All the accounts which have come down to us describe the furniture and decorations of Richmond Palace as superb, exhibiting in tapestries the deeds of kings and heroes.

Survey of 1649

The survey taken in 1649 affords a minute description of the palace. The great hall was 100 ft (30 m) in length, and 40 ft (12 m) in breadth, having a screen at the lower end, over which was "fayr foot space in the higher end thereof, the pavement of square tile, well lighted and seated; at the north end having a turret, or clock-case, covered with lead, which is a special ornament to this building." The prince's lodgings are described as a "freestone building, three stories high, with fourteen turrets covered with lead," being "a very graceful ornament to the whole house, and perspicuous to the county round about." A round tower is mentioned, called the "Canted Tower," with a staircase of 124 steps. The chapel was 96 ft (29 m) long and 40 ft (12 m) broad, with cathedral-seats and pews. Adjoining the prince's garden was an open gallery, 200 ft (61 m) long, over which was a close gallery of similar length. Here was also a royal library. Three pipes supplied the palace with water, one from the white conduit in the new park, another from the conduit in the town fields, and the third from a conduit near the alms-houses in Richmond.

Archaeology

During 1997 the site was investigated in the Channel 4 programme Time Team which was broadcast in January 1998.[12]

Lavatory innovation

This palace was one of the first buildings in history to be equipped with a flushing lavatory, invented by Elizabeth I's godson, Sir John Harington.[13] Henry VIII had earlier installed flushing latrines at Hampton Court.[14]

Richmond Palace today

Structures of the former palace that have survived include the Wardrobe, Trumpeters' House and the Gate House, all three of which are Grade I listed.[2][15][16] The Gate House was built in 1501, and was let on a 65-year lease by the Crown Estate Commissioners in 1986. It has five bedrooms.

References

- 1 2 "Richmond", in Encyclopædia Britannica, (9th edition, 1881), s.v.

- 1 2 Historic England (10 January 1950). "The Gate House The Old Palace (1065318)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- 1 2 3 "The mediaeval palace", London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

- 1 2 3 'Parishes: Richmond (anciently Sheen)', in A History of the County of Surrey: Volume 3, ed. H E Malden (London, 1911), pp. 533-546. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/surrey/vol3/pp533-546 [accessed 19 July 2020].

- ↑ Cumming, Ed (9 April 2014). "Inside the £3 Million Wren Wardrobe". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ↑ Ross, David. "Perpendicular Gothic architecture in England". Britain Express.

- ↑ Arnopp, Judith (7 December 2015). "English Historical Fiction Authors: A Not-So-Cool-Yule at Sheen Palace 1497". English Historical Fiction Authors.

- ↑ Weir, Alison (13 December 2013). Elizabeth of York: A Tudor Queen and Her World (1st ed.). Ballantine Books. p. 215. ISBN 978-0345521385. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ↑ Davison, Anita (5 July 2012). "English Historical Fiction Authors: The Lost Palace of Richmond".

- ↑ Weir, A. (2008). Henry VIII: The King and His Court. New York: Ballantine Books. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-345-43708-2.

- ↑ Colvin, Howard, ed., History of the King's Works, vol. 3 part 1, HMSO (1975), pp. 124-6

- ↑ "History". Channel 4. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ↑ Cloake, John (1995). Palaces and Parks of Richmond and Kew, Volume 1: The Palaces of Shene and Richmond. Chichester: Phillimore & Co. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-0850339765.

- ↑ Thurley, Simon. The Royal Palaces of Tudor England: Architecture & Court Life 1460-1547, London, 1993, p.177

- ↑ Historic England (25 June 1983). "The Wardrobe (1357730)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ↑ Historic England (10 January 1950). "The Trumpeters' House, Old Palace Yard (1357749)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 July 2020.