| Part of a series on |

| Shaivism |

|---|

|

|

|

Rudraksha (IAST: rudrākṣa) refers to the dried stones or seeds of the genus Elaeocarpus specifically, Elaeocarpus ganitrus.[1] These stones serve as prayer beads for Hindus (especially Shaivas), Buddhists and Sikhs.[2] When they are ripe, rudraksha stones are covered by an inedible blue outer fruit so they are sometimes called "blueberry beads[3]

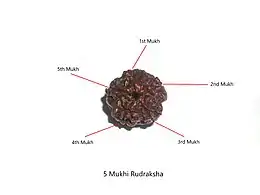

The stones are associated with the Hindu deity Shiva and are commonly worn for protection and for chanting mantras such as Om Namah Shivaya (Sanskrit: ॐ नमः शिवाय; Om Namaḥ Śivāya). They are primarily sourced from India, Indonesia, and Nepal for jewellery and malas (garlands) and valued similarly to semi-precious stones.[1] Rudraksha can have up to fourteen "faces" (Sanskrit: मुख, romanized: mukha, lit. 'face') or locules - naturally ingrained longitudinal lines which divide the stone into segments. Each face represents a particular deity.[4]

Etymology

Rudraksha is a Sanskrit compound word consisting of "Rudra"(Sanskrit: रुद्र) referring to Shiva and "akṣa"(Sanskrit: अक्ष) meaning "eye".[5][lower-alpha 1][6] Sanskrit dictionaries translate akṣa (Sanskrit: अक्ष) as eyes,[7] as do many prominent Hindus such as Sivaya Subramuniyaswami and Kamal Narayan Seetha; accordingly, rudraksha may be interpreted as meaning "eye of Rudra".[8][9]

Description

Rudraksha tree

Of the 300 species of Elaeocarpus, 35 are found in India. The principal species of this genus is Elaeocarpus ganitrus, which has the common name of "rudraksha tree", and is found from the Gangetic plain in the foothills of the Himalayas to Nepal, South and Southeast Asia, parts of Australia, Guam, and Hawaii.[10]

Elaeocarpus ganitrus trees grow to 60–80 ft (18–24 m). They are evergreen trees which grow quickly, and as they mature their roots form buttresses, rising up near the trunk and radiating out along the surface of the ground.

Fruit

The rudraksha tree starts bearing drupes (fruit) in three to four years from germination. It yields between 1,000 and 2,000 fruits annually. These fruits are commonly called "rudraksha fruit", but are also known as amritaphala (fruits of ambrosia).

The pyrena of the fruit, commonly called the "pit" or "stone", is typically divided into multiple segments by seed-bearing locules. When the fruit is fully ripe, the stones are covered with a blue outer fleshy husk of inedible fruit. The blue colour is not derived from a pigment but is due to structural colouration.[11] Rudraksha beads are sometimes called "blueberry beads" in reference to the blue colour of the fruit.

Chemical composition

Rudraksha fruits contain alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, steroids, triterpenes, carbohydrates, and cardiac glycosides. They also contain rudrakine,[12][13] an alkaloid which had been discovered in rudraksha fruit in 1979.[14]

Types of rudraksha stones

Rudraksha stones are described as having a number of facets or "faces" (mukhi) which are separated by a line or cleft along the stone. Stones typically have between 1 and 14 faces. Those with a single face (ekmukhi) are the rarest.[4][15] A Rudraskha with eleven faces is worn by renunciants, those who are married wear a two-faced stone and a five-faced stone is representative of Hanuman.[16] Rudrakshas from Nepal are between 20 and 35 mm (0.79 and 1.38 in) and those from Indonesia are between 5 and 25 mm (0.20 and 0.98 in). Rudraksha stones are most often brown, although white, red, yellow, or black stones may also be found.

Many types of stone are described. Gauri shankar are two stones which are naturally conjoined. Sawar are gauri shankar in which one of the conjoined stones has just one face. Ganesha are stones which have a trunk-like protrusion on their bodies. Trijuti are three stones which are naturally conjoined. Other rare types include veda (4 conjoined sawars) and dwaita (2 conjoined sawars).[17]

Uses

Religious uses in Indian-origin religions

Rudraksha is sacred to and popularly worn by devotees of Shiva.[4]

Rudraksha stones may be strung together as beads on a garland (mala) which can be worn around the neck. The beads are commonly strung on silk, or on a black or red cotton thread. Less often, jewellers use copper, silver or gold wires. The rudraksha beads may be damaged if strung too tightly. The Devi-Bhagavata Purana describes the preparation of rudraksha garlands.[19]

Hindus often use rudraksha garlands aids to prayer and meditation, and to sanctify the mind, body, and soul, much as Christians use prayer beads and rosaries to count repetitions of prayer.[20] There is a long tradition of wearing 108 rudraksha beads in India, particularly within Shaivism, due to their association with Shiva, who wears rudraksha garlands. Most garlands contain 108 beads plus one because as 108 is considered sacred and a suitable number of times to recite a short mantra. The extra bead, which is called the "meru", bindu, or "guru bead", helps mark the beginning and end of a cycle of 108 and has symbolic value as a 'principle' bead. Rudraksha garlands usually contain beads in combinations 27+1, 54+1, or 108+1. The mantra Om Namah Shivaya, associated with Shiva, is often chosen for repetitions (japa) using rudraksha beads.[21]

History

In Hindu religious texts

Upanishads

Several late-medieval Upanishads describe the construction, wearing, and use rudraksha garlands as well as their mythological origin as the tears of Rudra.

तं गुहः प्रत्युवाच प्रवालमौक्तिकस्फटिकशङ्ख रजताष्टापदचन्दनपुत्रजीविकाब्जे रुद्राक्षा इति । आदिक्षान्तमूर्तिः सावधानभावा । सौवर्णं राजतं ताम्रं तन्मुखे मुखं तत्पुच्छे पुच्छं तदन्तरावर्तनक्रमेण योजयेत्[22]

Sage Guha replied: (It is made of any one of the following 10 materials) Coral, Pearl, Crystal, Conch, Silver, Gold, Sandal, Putra-Jivika, Lotus, or Rudraksha. Each head must be devoted and thought of as presided over by the deities of Akara to Kshakara. Golden thread should bind the beads through the holes. On its right silver (caps) and left copper. The face of a bead should face, the face of another head and tail, the tail. Thus a circular formation must be made.[23]

अथ कालाग्निरुद्रं भगवन्तं सनत्कुमारः पप्रच्छाधीहि भगवन्रुद्राक्षधारणविधिं स होवाच रुद्रस्य नयनादुत्पन्ना रुद्राक्षा इति लोके ख्यायन्ते सदाशिवः संहारकाले संहारं कृत्वा संहाराक्षं मुकुलीकरोति तन्नयनाज्जाता रुद्राक्षा इति होवाच तस्माद्रुद्राक्षत्वमिति तद्रुद्राक्षे वाग्विषये कृते दशगोप्रदानेन यत्फलमवाप्नोति तत्फलमश्नुते स एष भस्मज्योती रुद्राक्ष इति तद्रुद्राक्षं करेण स्पृष्ट्वा धारणमात्रेण द्विसहस्रगोप्रदानफलं भवति । तद्रुद्राक्षे एकादशरुद्रत्वं च गच्छति । तद्रुद्राक्षे शिरसि धार्यमाणे कोटिगोप्रदानफलं भवति[24]

Sage Sanatkumara approached Lord Kalagni Rudra and asked him, "Lord, kindly explain to me the method of wearing Rudraksha." What he told him was, "Rudraksha became famous by that name because initially, it was produced from the eyes of Rudra. During the time of destruction and after the act of destruction, when Rudra closed his eye of destruction, Rudraksha was produced from that eye. That is the Rudraksha property of Rudraksha. Just by touching and wearing this Rudraksha, one gets the same effect of giving in charity one thousand cows."[25]

तुलसीपारिजातश्रीवृक्षमूलादिकस्थले । पद्माक्षतुलसीकाष्ठरुद्राक्षकृतमालया[26]

He should count using a rosary (mala) whose beads are either made of the tulsi plant or rudraksha.[27]

हृदयं कुण्डली भस्मरुद्राक्षगणदर्शनम् । तारसारं महावाक्यं पञ्चब्रह्माग्निहोत्रकम्[28]

After prostrating himself before the celebrated form of Sri Mahadeva-Rudra in his heart, adoring the sacred Bhasma and Rudraksha and mentally reciting the great Mahavakya-Mantra, Tarasara, Sage Shuka asked his father Geat Sage Vyasa.[29]

अथ हैनं कालाग्निरुद्रं भुसुण्डः पप्रच्छ कथं रुद्राक्षोत्पत्तिः । तद्धारणात्किं फलमिति । तं होवाच भगवान्कालाग्निरुद्रः । त्रिपुरवधार्थमहं निमीलिताक्षोऽभवम् ।निमीलिताक्षोऽभवम् तेभ्यो जलबिन्दवो भूमौ पतितास्ते रुद्राक्षा जाताः । सर्वानुग्रहार्थाय तेषां नामोच्चारणमात्रेण दशगोप्रदानफलं दर्शनस्पर्शनाभ्यां द्विगुणं फलमत ऊर्ध्वं वक्तुं न शक्नोमि[30]

Sage Bhusunda questioned Lord Kalagni-Rudra: What is the beginning of Rudraksha beads? What is the benefit of wearing them on the body? Lord Kalagni-Rudra answered him thus: I closed my eyes for the sake of destroying the Tripurasura. From my eyes thus closed, drops of water fell on the earth. These drops of tears turned into Rudrakshas. By the mere utterance of the name of 'Rudraksha', one acquires the benefit of giving ten cows in charity. By seeing and touching it, one attains double that benefit. I am unable to praise it anymore.[31]

Tirumurai

Like the Upanishads, the Tirumurai describes the wearing of rudraksha garlands and their use as prayer beads for chanting mantras. Accordingly, the Tirumurai identifies wearing a pair of rudraksha garlands as a sign of piety.

They who walk the twin paths of charya and kriya ever praise the twin feet of the Lord. They wear holy emblems—the twin rings in earlobes, the twin rudraksha garland around the neck—and adopt the twin mudras, all in amiable constancy.

Thinking of Him, great love welling up in their heart, if they finger the rudraksha beads, it will bring them the glory of the Gods. Chant our naked Lord’s name. Say, “Namah Shivaya!”

Cultivation

Herbal and sacred groves

Ch. Devi Lal Rudraksha Vatika, is a 184 acres (0.74 km2) grove dedicated to rudraksha which also has over 400 endangered ayurvedic medicinal herbs in Yamunanagar district of Haryana state in India.[34]

Rudraksha is primarily cultivated in the foothills of the Himalayas, mainly in Nepal and India.[35] The most popular varieties of rudraksha are found in the regions of Kathmandu, Kulu, and Rameshwaram in India. There are several naturally occurring trees of rudrakshas in the alpine forests of Dhauladhar and lower Shivalik ranges of the Himalayas.

Groves are mostly found in Uttarakhand state of India.

Gallery

Tree

Rudraksha tree leaves

Rudraksha tree leaves Rudraksha tree with flowers

Rudraksha tree with flowers Rudraksha flowers

Rudraksha flowers Countries to which Elaeocarpus ganitrus is native.

Countries to which Elaeocarpus ganitrus is native.

Fruit

Unripe rudraksha fruit on the tree

Unripe rudraksha fruit on the tree On drying rudraksha fruits turn black

On drying rudraksha fruits turn black Freshly plucked raw rudraksha fruits; when ripe these are blue in colour

Freshly plucked raw rudraksha fruits; when ripe these are blue in colour Ripe rudraksha fruits with typical blue colour

Ripe rudraksha fruits with typical blue colour

Stones

Handful of rudraksha stones

Handful of rudraksha stones Red 5-faced rudraksha stone

Red 5-faced rudraksha stone Cross-section of a 7-faced rudraksha stone

Cross-section of a 7-faced rudraksha stone X-ray of 10-faced rudraksha stone reveals 10 seeds storing chambers (locules) and one central chamber

X-ray of 10-faced rudraksha stone reveals 10 seeds storing chambers (locules) and one central chamber

See also

- Similar religiously-significant natural objects

- Associated mantras

- Prayer beads

- Garlands and beadwork

Notes

- ↑ Stutley (1985), p. 119:"'Rudra-eyed'. Name of the dark berries of Elaeocarpus ganitrus, used to make Śaiva rosaries (mālā), or necklaces. The berries have five divisions symbolising Śiva's five faces (pañcānana)."

References

- 1 2 Bhattacharyya, Bharati (2015-10-02). Golden Greens: The Amazing World of Plants. The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI). pp. 21–25. ISBN 978-81-7993-441-8.

- ↑ Singh M Parashar (13 November 2019). Inner and Outer Meanings of Hinduism. Xlibris UK. pp. 229–. ISBN 978-1-984592-11-8.

- ↑ Singh, B; Chopra, A; Ishar, MP; Sharma, A; Raj, T (2010). "Pharmacognostic and antifungal investigations of Elaeocarpus ganitrus (Rudrakasha)". Indian J Pharm Sci. 72 (2): 261–5. doi:10.4103/0250-474X.65021. PMC 2929793. PMID 20838538.

- 1 2 3 Lochtefeld, James G. (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. Rosen. p. 576. ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4.

- ↑ Stutley, M. (1985). The Illustrated Dictionary of Hindu Iconography. New Delhi, India: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. pp. 98, 119. ISBN 978-81-215-1087-5.

- ↑ Singh, Ishar B. (2015). "Phytochemical and biological aspects of Rudraksha, the stony endocarp of Elaeocarpus ganitrus". Israel Journal of Plant Sciences. 62 (4): 265–276 – via Brill.

- ↑ "Aksa: English Translation of the Sanskrit word: Aksa-- Sanskrit Dictionary".

- ↑ Subramuniyaswami, Sivaya (1997). Dancing with Siva. USA. Search for "Rudraksha" on the page. ISBN 9780945497974.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Ziegenbalg, Bartholomaeus (1869). Genealogy of the South-Indian Gods: A Manual of the Mythology and Religion of the People of Southern India, Including a Description of Popular Hinduism. Higginbotham. p. 27.

- ↑ Koul, M. K. (2001-05-13). "Bond with the beads". Spectrum. India: The Tribune.

- ↑ Lee, D. W. (1991). "Ultrastructural Basis and Function of Iridescent Blue Color of Fruits in Elaeocarpus". Nature. 349 (6306): 260–262. Bibcode:1991Natur.349..260L. doi:10.1038/349260a0. S2CID 13332325.

- ↑ "Rudrakine chemical". Research gate.

- ↑ Jawla, Sunil; Rai, D. V. (2016-06-08). "QSAR Descriptors of Rudrakine Molecule of Rudraksha (Elaeocarpus ganitrus) Using Computation Servers". German Journal of Pharmacy and Life Science (GJPLS). 1 (1).

- ↑ Ray, A.B.; Chand, Lal; Pandey, V.B. (January 1979). "Rudrakine, a new alkaloid from Elaeocarpus ganitrus". Phytochemistry. 18 (4): 700–701. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)84309-5.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ↑ Dalal, Roshen (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. pp. 1668–1669. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ↑ Blackman, Winifred S. (1918). "The Rosary of Magic and Religion". Folklore. 29 (4): 255–280 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Seetha, Kamal Narayan (2005). Power of rudraksha. India. pp. 15, 20 and 21. ISBN 9788179929810.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ For the five-division type as signifying Shiva's five faces and terminology pañcānana, see: Stutley, p. 119.

- ↑ Seetha, Kamal Narayan (2008). Power of Rudraksha (4th ed.). Mumbai, India: Jaico Publishing House. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-81-7992-844-8.

- ↑ Laatsch, M. (2010). Rudraksha. Die Perlen der shivaitischen Gebetsschnur in altertümlichen und modernen Quellen. Munich: Akademische Verlagsgemeinschaft München. ISBN 978-3-89975-411-7.

- ↑ "Dancing with Siva". www.himalayanacademy.com. Retrieved 2018-04-07.

- ↑ "AkShamalika Upanishad sanskrit\" (PDF).

- ↑ "AkShamalika Upanishad english".

- ↑ "Brihat-Jabala Upanishad sanskrit".

- ↑ "Brihad Jabala Upanishad english".

- ↑ "shrIRamarahasya Upanishad sanskrit".

- ↑ "Rama Rahasya Upanishad english".

- ↑ "Rudrahridaya Upanishad sanskrit".

- ↑ "Rudra Hridaya Upanishad english".

- ↑ "rudrakshajabala sanskrit" (PDF).

- ↑ "Rudraksha Jabala Upanishad english".

- ↑ Dancing with Siva. Himalayan Academy. 1997. ISBN 9788120832657.

- ↑ Dancing with Siva. Himalayan Academy. 1997. ISBN 9780945497479.

- ↑ PM News Bureau. "Herbal Park at Hisar". old.projectsmonitor.com. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ↑ "Breaking the cycle of poverty with education in the most remote parts of the world". The Independent. 2021-05-01. Retrieved 2023-01-25.