The Ruhr Question was a political topos put on the agenda by the Allies of World War I and the Allies of World War II in the negotiations following each respective war, concerning how to deal with the economic and technological potential of the area where the Rhine and Ruhr intersect. France was heavily in favor of monitoring this region, due to the perception that the economic and technological potential of the region had allowed the German Reich to threaten and occupy France during the Franco-Prussian War, World War I, and World War II. The Ruhr question was intimately associated with the Saar Statute and the German Question. There was also a close relationship between the Ruhr Question and the Allied occupation of the Rhineland (1919-1930), the Occupation of the Ruhr (1923-1924, 1925), the founding of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia (1946), the International Authority for the Ruhr (1949-1952), the Schuman Declaration (1950), and the founding of the European Coal and Steel Community (1951). The political treatment of the Ruhr question is known as Ruhrpolitik in German. When one looks at the Rhineland as a whole or the attempted establishment of the Rhenish Republic in 1923, the terms Rhein- und Ruhrfrage or Rhein-Ruhr-Frage are used in German.[1][2]

History

Ruhr Occupation

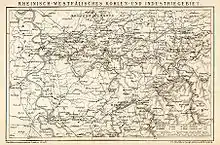

As early as the beginning of the 1920s, the Ruhrfrage was an important subject of dispute between France and Germany. From the French perspective, the region and a big portion of the industries of the Rhein and Ruhr, such as the arms industry of Krupp in Essen and Rheinmetall in Düsseldorf, was known as the "Armory of Germany". After France had suffered at the hands of this "armory" in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 and the First World War of 1914–1918, the negotiations leading to the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 resulted in the creation of a "security glacis" against Germany in the form of the cessation of the Left Bank of the Rhine, extensive demilitarization, armament restrictions, and the Allied occupation of the Rhineland. In addition, France was able to achieve considerable reparations from Germany after the first World War. If the German Reich could not meet the requirements of the reparations, the negotiation terms of the Londoner Zahlungsplan threatened to divide the Ruhr through forced occupation. At this time, the Ruhr was known as the Rhine-Westphalian coal and industrial area, including Lippe in the north, Dortmund in the east, and Düsseldorf in the south. Germany defaulted on reparations, causing France and Belgium to occupy the cities of Düsseldorf, Duisburg, and Ruhrort in 1921 and the remaining Ruhr area stretching east to Dortmund in 1923. The occupation of the Ruhr, including control of the factories and coal mines, lasted until the agreement of the Dawes Plan in 1924. The confiscated Stahlhof (lit. "Steel Court") of Düsseldorf served as the command center of the occupation of the Ruhr until the French withdrew on August 25, 1925.

Reorganization of Germany and Europe after the Second World War

At the end of the Second World War, the Allies once again asked themselves how to deal with the economic and technological potential of the Rhine and Ruhr. When the French were deliberating the future of Germany, the Ruhr Question was their top priority. The industrialized area of the Rhine and Ruhr, highly stylized in Nazi propaganda as the "armory of the empire", represented for France at the end of World War II far more than merely an Industrial region. Rather, the Ruhr was "a symbol of German Power and a source of French humiliation".[3] As early as February 5, 1945, France's provisional head of government Charles de Gaulle broadcast a speech introducing the vision of a "Ruhr basin" ("Ruhrbecken") as free from a future German state or German states. At the conferences of the Allies, the question of the Ruhr came more and more into the agenda, mostly due to French proposals. At the Foreign Minister's Conference, which took place in London from September 11, 1945, until October 2, 1945, French foreign minister Georges Bidault issued a memorandum of 13 September 1945. This memorandum stated that the separation of the Rhineland and Westphalia, including the Ruhr area of the German Reich, as "indispensable for the protection of the frontier and an essential prerequisite for the security of Europe and the world."[4] The Soviet Union wanted the industrial area on the Rhine and Ruhr placed under common control of all four powers, as stipulated by the Berlin Declaration (1945). The three Western Allies disliked the idea of the Soviet Union reaping the benefits of the industrial area of the Rhine and the Ruhr. Basic differences of opinion led to tensions between the Soviet Union and Western Allies over various questions concerning the re-organization of Europe and the World. These tensions caused the Allied Control Council to break down, leading to the beginning of the Cold War.

A decisive opponent of French annexation or supremacy of the Rhine and Ruhr was British Foreign Minister, Ernest Bevin. In a memorandum issued on June 13, 1946, Bevin wrote about the Ruhr question with a historical view of the Ruhr occupation from 1923 to 1925 and its consequences for the Weimar Republic:[5]

Finally, it is impossible to consider this question without reference to the disastrous Ruhr experiment of 1923, when the French tried to put into operation similar plans to those which they have now put forward and for the same reasons. This experiment retarded the recovery of Europe after the last war, precipitated the great inflationary wave of 1923–25 and stifled the infant Republic of Weimar and so contributed to paving the way of National Socialism. The fact that the French forget this experiment in their present arguments is yet another proof, that, as a result of their experiences at the hand of the Germans they are unable to view this question in a balanced and objective manner. Because we sympathise with sufferings there is no reason why we should adopt the restated view which results from them.

_01_ies.jpg.webp)

The French side often encountered resistance to their proposals for the solution of the Ruhr Question. This was especially true in the case of the British and Americans. The British had pursued their own concept when founding the state of Northrhine-Westphalia by nearly socializing the coal and steel industry. The Americans had operated under the containment of the Truman Doctrine with the objectives of the Marshall Plan. Thus, the Americans refused to dismantle, and defused the socialization plans of the British. The Americans first came up with the concept of a "Ruhr Charter" in 1948, providing for international supervision of and international access to coal and steel products from the Rhine and Ruhr. The Soviets, however, were left out of the American-born "Ruhr Charter" concept, given no access nor oversight. The "Ruhr Charter" was the idea that served as the basis for further discussion among the Western allies. The final resolution of the Ruhr question came with the London 6-Power Conference in 1948. The three western allies and the Benelux countries agreed on the joint development of a concept for an international authority providing international access to the German coal and steel market. The next step was creating a German central government in West Germany in accordance with the Frankfurt Documents.[6] The Ruhr office became official in 1949, setting up the International Authority for the Ruhr in Düsseldorf. This agency controlled about 40% of German industrial production. The Parlamentarischer Rat of West Germany rejected the International Authority for the Ruhr as discrimination. Karl Arnold, the Prime Minister of North Rhine-Westphalia, agreed with the other Prime Ministers of the German states to accept the International Authority for the Ruhr on the condition that other coal and steel locations in the West of Europe were put under the same control. This condition was not met by the Ruhr statute, but discussions subsequently went in the direction of an economic union of European countries.[7] With the Petersberg Agreement on November 22, 1949, the first federal government under Konrad Adenauer accepted the International Authority for the Ruhr.[8] In December 1949, West Germany officially gained voting rights in the International Authority for the Ruhr. This laid the foundations for the Schuman Declaration of 1950, which laid the groundwork for the founding of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951. This French-born idea of the ceding of French political authority towards the creation of a "European structure" was previously laid out in a memorandum written by Jean Monnet in Algiers on August 5, 1943.[9] This 1943 memorandum envisaged a prototype of the current Community method used to make decisions in the modern day European Union.

Historical interpretation

The shift of France concerning Ruhr and German policy after the Second World War towards a "communalization" of the coal and steel industries, which was opened by the Schuman Plan, is explained by a cognitive process on the French side. France had gradually realized that their harsh Germany policy under the foreign minister Raymond Poincaré was ultimately the result of a personal vendetta, thus failing the ultimate goals of the French state. Another explanation of the shift in French attitudes can be found in the Marshall Plan. In order to finance their own reconstruction, France had to take part in the Westintegration of West Germany. France's participation in the "Westintegration" was laid down by the American policy of containment in particular.[10][11]

References

- Raymond Poidevin: Frankreich und die Ruhrfrage 1945–1951. In: Historische Zeitschrift, 228, 2 (April 1979), Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, P. 317–334

- Raimond Poidevon: Der Faktor Europa in der Deutschland-Politik Robert Schumans (Sommer 1948 bis Frühjahr 1949). In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, 1985, 3, S. 406 ff. Full Text

- John Gillingham: Die französische Ruhrpolitik und die Ursprünge des Schuman-Plans. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, 1987, 1, P. 1 ff. Full Text

- Rolf Steininger: Die Ruhrfrage 1945/1946 und die Entstehung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen. Britische, französische und amerikanische Akten. In: The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 62, No. 3 (September 1990), University of Chicago Press, P. 665–667

- Ursula Rombeck-Jaschinski: Nordrhein-Westfalen, die Ruhr und Europa. Föderalismus und Europapolitik 1945–1955. Düsseldorfer Schriften zur Neueren Landesgeschichte und zur Geschichte Nordrhein-Westfalens, Tape 29, Düsseldorf 1990

- Gaston Haelling: Importance de la Ruhr pour le Bénélux. In: Politique étrangère, 1949, Vol. 14, No. 1, P. 49–62 Digitalisat

References

- ↑ Vgl. etwa Theodor Schieder: Die Probleme des Rapallo-Vertrags. Eine Studie über die deutsch-russischen Beziehungen 1922–1926. Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Forschung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen, Abhandlung, Heft 43, Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1956, ISBN 978-3-663-00298-7, S. 53

- ↑ Vgl. auch Akten der Reichskanzlei: Weimarer Republik: Die Kabinette Marx I/II: Ministerbesprechung vom 24. Januar 1924 (Band 1, Dokumente, Nr. 73, Abschnitt Nr. 4, Buchstabe a: Rhein-Ruhr-Frage: Verhandlungen des Wirtschaftsausschusses), Webseite im Portal bundesarchiv.de, retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ↑ John Gillingham, S. 4

- ↑ Rolf Steininger: Reform und Realität. Ruhrfrage und Sozialisierung in der anglo-amerikanischen Deutschlandpolitik 1947/48. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte. Heft 2 (April 1979), S. 168 (PDF)

- ↑ Ernest Bevins Memorandum vom 13. Juni 1946. In: Rudolf Steininger: Die Ruhrfrage 1946/47 und die Entstehung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen. Britische, französische und amerikanische Akten. Düsseldorf 1988, Dokument 188, S. 883–887. Zitiert nach: Wilhelm Ribhegge: Braucht Nordrhein-Westfalen ein Haus der Geschichte? In: Saskia Handro, Bernd Schönemann (Hrsg.): Raum und Sinn. Die räumliche Dimension der Geschichtskultur. LIT Verlag Dr. W. Hopf, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-643-12483-8, S. 134 (Google Books)

- ↑ Rolf Steininger, S. 236 f.

- ↑ Raymond Poidevin: Der Faktor Europa in der Deutschlandpolitik Robert Schumans. S. 418

- ↑ Klaus Joachim Grigoleit: Bundesverfassungsgericht und deutsche Frage. Schriftenreihe Jus Publicum, Heft 107, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2004, ISBN 3-16-148367-7, S. 227 (Google Books)

- ↑ Fondation Jean Monnet pour l'Europe, Lausanne, Archives Jean Monnet, Fonds AME. 33/1/4: "Note de réflexion de Jean Monnet," 5 August 1943, Volltext, hier S. 2 (scrollen): wörtlich "entité européenne". Vgl. John Gillingham, S. 4

- ↑ Franz Knipping: Que faire de l'Allemagne? Die französische Deutschlandpolitik 1945–1950. In: Franz Knipping, Ernst Weisenfeld (Hrsg.): Eine ungewöhnliche Geschichte: Deutschland – Frankreich seit 1870. Europa Union Verlag, Bonn 1988, S. 148

- ↑ Anne-Kristin Krämer: Die Angst in Frankreich vor Deutschland als Motor der europäischen Integration. Diplomarbeit, Fachhochschule Köln, Bochum 1999, S. 23 (PDF)

External links

- Die Ruhrfrage, Website at the URL cvce.eu