.jpg.webp)

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.[1][2]

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who often faced displacement, subjugation, slavery, rape and execution) was often as unapologetic as "because we can" treading on the philosophical grounds of might makes right.

As political conceptions of the nation state evolved, especially in reference to the inherent rights of the governed, more complex justifications arose. State-collapse anarchy, reunification or pan-nationalism are sometimes used to justify and legitimize expansionism when the explicit goal is to reconquer territories that have been lost or to take over ancestral lands.

Lacking a viable historical claim of this nature, would-be expansionists may instead promote ideologies of promised lands (such as manifest destiny or a religious destiny in the form of a Promised Land), perhaps tinged with a self-interested pragmatism that targeted lands will eventually belong to the potential invader anyway.[3]

Theories

Ibn Khaldun wrote that newly established dynasties, because they have social cohesion or Asabiyyah, are able to seek "expansion to the limit."[4]

The Soviet economist Nikolai Kondratiev theorized that capitalism advances in 50-year expansion/stagnation cycles, driven by technological innovation. The UK, Germany, the US, Japan and now China have been at the forefront of successive waves.

Crane Brinton in The Anatomy of Revolution saw the revolution as a driver of expansionism in, for example, Stalinist Russia, the United States and the Napoleonic Empire.

Christopher Booker believed that wishful thinking can generate a "dream phase" of expansionism such as in the European Union, which is short-lived and unreliable.

According to a 2023 study, important historical instances of territorial expansion have frequently happened because actors on the periphery of a state have acted without authorization from their superiors at the center of the state. Leaders subsequently find it difficult to withdraw from the newly captured areas due to "sunk costs, domestic political pressure, and national honor."[5]

Examples

Every part of the world has experienced expansionism.[6][7] The religious imperialism and colonialism of Islam started with the early Muslim conquests, was followed by the religious Caliphate expansionisms, and ended with the Partition of the Ottoman Empire. In the 15th and 16th centuries, the Ottoman Empire entered a period of expansion. The Ottomans ended the Eastern Roman Empire with the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by Mehmed the Conqueror.[8]

The militarist and nationalistic reign of Russian Czar Nicholas I (1825–1855) led to wars of conquest against Persia (1826–1828) and Turkey (1828–1829). Various rebel tribes in the Caucasus region were crushed. A Polish revolt in 1830 was ruthlessly crushed. Russian troops in 1848 crossed into Austria-Hungary to put down the Hungarian Revolt. Russification policies were implemented to weaken minority ethnic groups. Pan-Slavist solidarity led to further war with Turkey (the sick man of Europe) in 1853 provoked Britain and France into invading Crimea.[9]

In Italy, Benito Mussolini sought to create a New Roman Empire, based around the Mediterranean. Italy invaded Ethiopia as early as 1935, Albania in early 1938, and later Greece. Spazio vitale ("living space") was the territorial expansionist concept of Italian Fascism. It was analogous to Nazi Germany's concept of Lebensraum and the United States' concept of "Manifest Destiny". Fascist ideologist Giuseppe Bottai likened this historic mission to the deeds of the ancient Romans.[10]

After 1937, Nazi Germany under Hitler laid claim to Sudetenland, unification (Anschluss) with Austria in 1938 and the occupation of the whole of the Czech lands the following year. After war broke out, Hitler and Stalin divided Poland between Germany and the Soviet Union. In a Drang nach Osten aimed at achieving Lebensraum for the German people, Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941.[11]

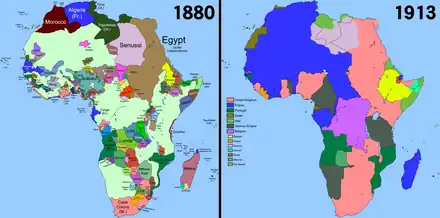

Expansionist nationalism is an aggressive and radical form of nationalism that incorporates autonomous patriotic sentiments with a belief in expansionism. The term was coined during the late 19th century as European powers indulged in the Scramble for Africa, but it has been most associated with militarist governments during the 20th century including Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany, the Japanese Empire, and the Balkans countries of Albania (Greater Albania), Bulgaria (Greater Bulgaria), Croatia (Greater Croatia), Hungary (Greater Hungary), Romania (Greater Romania) and Serbia (Greater Serbia).

In American politics after the War of 1812, Manifest Destiny was the ideological movement during America's expansion West. The movement incorporated expansionist nationalism with continentalism, with the Mexican War in 1846–1848 being attributed to it. Despite championing American settlers and traders as the people whom the government's military would be aiding, the Bent, St. Vrain and Company stated to be the most influential Indian trading company prior to the Mexican War, underwent a decline because of the and of traffic from American settlers by Beyreis. The company also lost the partner Charles Bent on January 19, 1847, to a riot caused by the Mexican War. Many in the Cheyennes, Comanches, Kiowas, and Pawnees tribes died from smallpox in 1839–1840, measles and whooping cough in 1845, and cholera in 1849, which had been brought by American settlers. The buffalo herds, sparse grasses, and rare waters were also depleted following the war as increased traffic by settlers moving to California during the Gold Rush.[12]

21st century

China

The People's Republic of China is accused of expansionism through its operations and claims in the South China Sea, which are concurrently claimed by Vietnam.[13]

Israel

Israel was established on reacquired lands under international law and a manifest of original ownership on May 14, 1948, after the end of World War II and the Holocaust. Its government has occupied the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights, and the Sinai Peninsula since the Six-Day War, although the Sinai was later returned to Egypt in 1982[14][15][16] and Israel disengaged from the Gaza Strip in 2005.

Iran

Iran, the largest Shi'ite state, has extended its influence across the entire Middle East, including Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Yemen and Afghanistan by arming local militias.[17]

Russia

Russia under Vladimir Putin has had an aggressive posture since 2008, especially since 2014.[18] Events associated with Russia are the 2008 Russo-Georgian War and Russia's occupation of South Ossetia and Abkhazia; the Russo-Ukrainian War, which began in 2014 with the Annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas and escalated into the ongoing full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022; and the military intervention in Syria.

Turkey

Turkey's foreign policy is characterized, especially since 2010s by an aggressive expansionism, irredentism and interventionism in the Eastern Mediterranean and the neighboring Cyprus, Greece, Iraq, Syria, as well as in Africa, including Libya, and Nagorno-Karabakh.[lower-alpha 1] Turkey has occupied foreign territories and stationed troops in them, following the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus, the Turkish occupation of northern Syria since 2016 and the Turkish presence in northern Iraq since 2018.[25]

United States

The US retains military bases in some of the sovereign countries that it once occupied on a notionally-voluntary basis, including in Germany, Italy, Japan, Greenland, Iceland, Iraq, and formerly in Afghanistan. Guantanamo Bay Naval Base is retained despite the protests of the Cuban government, and the US has military bases in various other countries with which it has allied.

Ideologies

In the 19th century, theories of racial unity evolved such as Pan-Germanism, Pan-Slavism, and Pan-Turkism and the related Turanism. In each case, the dominant nation (respectively, Prussia; the Russian Empire;[26] and the Ottoman Empire, especially under Enver Pasha) used those theories to legitimise their expansionist policies.

American ideology

In terms of Ideological reasons for American expansion, this goes back to the 19th century when Frederick Turner produced his Frontier Thesis which made the case for American expansionism on the North American continent and that this turning point marked the beginning of a new epoch.[27] The case for expansionism was made under the umbrella of advances in the American economy and democracy. Furthermore, this was aided at the latter end of the 19th century by the belief of Anglo Saxon and subsequent American superiority. This was exacerbated by a recession for the first time in 20 years and the Americans believed that they could unload their goods on to people because they had a God given right to do so.[28] Their economic intentions were also supplemented by the fact that the Anglo Saxon race believed that they were simply better at governing a nation.[29] Furthermore, there was also a belief that white people were simply superior.[29] This racial superiority complex meant that some believed they had a right to enact their beliefs upon people who did not agree, such as Cuba, Guam and the Philippines.

Pan Americanism was a driver of governmental actors in the period, as the Harrison administration attempted to push through Pan American and tariff policies through the house and senate, however, their efforts were to no avail,[28] but this showed that Pan Americanism was a driver in the efforts of the government for American expansion.

Further expansion came off the American continent, in the Philippines, at the turn of the century which was arguably driven by a paternalistic United States as McKinley’s objectives, he declared in mid-1899, were fourfold: “Peace first, then a government of law and order honestly administered, full security to life, property, and occupation under the Stars and Stripes.”[30] However, the Philippines government was dictated by the Americans and ordinary Filipino people were not afforded the same privileges as the Americans that had been sent there.

It has also been posited that American leaders were pressured under traditional gender roles, which in turn made expansionism more likely. By the end of the 19th century President McKinley had been accustomed to being evaluated in terms of his manliness.[31] This also played in to the fact that in the late nineteenth century, men saw supporting the military as the ultimate test of being a man.[31] As a result, expansionism was a way of projecting manliness onto the electorate and in to society.

In popular culture

George Orwell's satirical novel Animal Farm is a fictional depiction, based on Stalin's Soviet Union, of a new elite seizing power, establishing new rules and hierarchies, and expanding economically while they compromise their ideals.

Robert Erskine Childers's novel The Riddle of the Sands portrays the threatening nature of the German Empire.

Elspeth Huxley's novel Red Strangers shows the effects on local culture of colonial expansion into Sub-Saharan Africa.

See also

- American imperialism

- British Empire

- French colonial empire

- Colonialism

- Early Muslim conquests

- Ethnic cleansing

- European colonization of the Americas

- Expansionist nationalism

- Greater Israel

- Irredentism

- List of irredentist claims or disputes

- Manifest Destiny

- Scramble for Africa, late 19th century

- Spread of Islam

References

- ↑

An alternative definition sees "expansionism" as "a desire to annex additional territory" for reasons such as perceived needs for Lebensraum or resources, the intimidation of rivals, or the projection of an ideology.May, Ronald James, ed. (1979). The Indonesia-Papua New Guinea Border: Irianese Nationalism and Small State Diplomacy. Department of Political and Social Change, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. p. 43. ISBN 9780908160334. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

At this point, however, we must define 'expansionism' a little more precisely. I am interpreting it to mean a desire to annex additional territory either

[...]- for the sake of more lebensraum (living space) or resources (oil, copper, timber, etc.);

- for the sake of demonstrating the national power so as to intimidate neighbours;

- because of an ideology of national greatness, power

- ↑ Knorr, Klaus (1952). Schumpeter, Joseph A.; Arendt, Hannah (eds.). "Theories of Imperialism". World Politics. 4 (3): 402–431. doi:10.2307/2009130. ISSN 0043-8871. JSTOR 2009130. S2CID 145320143.

- ↑ "Manifest Destiny | History, Examples, & Significance". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- ↑ The Muqadimmah, 1377, pages 137-256

- ↑ Anderson, Nicholas (2023). "Push and Pull on the Periphery: Inadvertent Expansion in World Politics". International Security. 47 (3): 136–173. doi:10.1162/isec_a_00454. S2CID 256390941.

- ↑ See Abernethy (2009); Darwin (2008)

- ↑ Wade, (2014).

- ↑ Quataert, Donald (2005). The Ottoman Empire, 1700–1922 (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-521-83910-5.

- ↑ Orlando Figes, Crimea (Penguin, 2011), chapter one

- ↑ Rodogno, Davide (2006). Fascism's European Empire: Italian Occupation During the Second World War. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-0-521-84515-1.

- ↑ Sebastian Haffner, The Meaning of Hitler, Phoenix, 2000, chapters 2, 3 and 4

- ↑ Beyreis, David (Summer 2018). "The Chaos of Conquest: The Bents and the Problem of American Expansion". Kansas History. 41 (2): 72–89 – via History Reference Center.

- ↑ Simon Tisdall, 'Vietnam's fury at China's expansionism can be traced to a troubled history', The Guardian, 15/5/2004

- ↑ "Carter Says Error Led U.S. to Vote Against Israelis". Washington Post. 4 March 1980. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ↑ Masalha, Nur (2000). Imperial Israel and the Palestinians: politics of expansion. Sterling, VA: Pluto Press.

- ↑ "Golan Heights Law". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 14 December 1981. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ↑ Arango, Tim (15 July 2017). "Iran Dominates in Iraq After U.S. 'Handed the Country Over'". New York Times. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ↑ Walker, Peter (2015-02-20). "Russian expansionism may pose existential threat, says NATO general". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-10-04.

- ↑ Antonopoulos, Paul (2017-10-20). "Turkey's interests in the Syrian war: from neo-Ottomanism to counterinsurgency". Global Affairs. 3 (4–5): 405–419. doi:10.1080/23340460.2018.1455061. ISSN 2334-0460. S2CID 158613563.

- ↑ Danforth, Nick (23 October 2016). "Turkey's New Maps Are Reclaiming the Ottoman Empire". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- ↑ "Turkey's Dangerous New Exports: Pan-Islamist, Neo-Ottoman Visions and Regional Instability". Middle East Institute. 21 April 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ↑ Sinem Cengiz (7 May 2021). "Turkey's militarized foreign policy provokes Iraq". Arab News. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ↑ Asya Akca (8 April 2019). "Neo-Ottomanism: Turkey's foreign policy approach to Africa". Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ↑ Slaviša Milačić (23 October 2020). "The revival of neo-Ottomanism in Turkey". World Geostrategic Sights. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ↑ Yousif Ismael (18 May 2020). "Turkey's Growing Military Presence in the Kurdish Region of Iraq". Washington Institute. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ↑ Orlando Figes, Crimea, Penguin, 2011, p.89

- ↑ LaFeber, Walter (1963). The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion 1860 - 1898. United States of America: Cornell University Press. p. 95. ISBN 0-8014-9048-0.

- 1 2 LaFeber, Walter (1963). The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion 1860 - 1898. United States of America: Cornell University Press. p. 112. ISBN 0-8014-9048-0.

- 1 2 Burnett, Christina; Marshall, Burke (2001). Foreign in a Domestic Sense: Puerto Rico, American Expansion, and the Constitution. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 26. ISBN 1-283-06210-0.

- ↑ LaFeber, Walter (2013-04-08). The New Cambridge History of American Foreign Relations (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139015677. ISBN 978-1-139-01567-7.

- 1 2 Hoganson, Kristin (1998). Fighting for American Manhood. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-300-08554-9.

Further reading

- Abernethy, David B. The dynamics of global dominance: European overseas empires, 1415-1980 (Yale University Press, 2000).

- Darwin, John. After Tamerlane: the global history of empire since 1405 ( Bloomsbury, 2008).

- Edwards, Zophia, and Julian Go. "The Forces of Imperialism: Internalist and Global Explanations of the Anglo-European Empires, 1750–1960." Sociological Quarterly 60.4 (2019): 628–653.

- MacKenzie, John M. "Empires in world history: characteristics, concepts, and consequences." in The Encyclopedia of Empire (2016): 1-25.

- Wade, Geoff, ed. Asian Expansions: The Historical Experiences of Polity Expansion in Asia (Routledge, 2014).

- Wesseling, Hendrik. The European Colonial Empires: 1815-1919 (Routledge, 2015).