| Sørup runestone | |

|---|---|

| |

| Created | 1050-1250[1] |

| Discovered | Currently Copenhagen, originally Sørup, Currently Zealand, originally Funen, Denmark |

| Rundata ID | DR 187 |

| Text – Native | |

| See article. | |

| Translation | |

| See article. | |

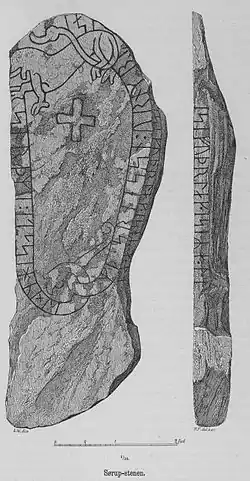

The Sørup runestone (Danish: Sørup-stenen) is a runestone from Sørup close by Svendborg on southern Funen in Denmark. The stone has a relatively long and very debated runic inscription, which has been seen as an unsolved cipher or pure nonsensical, but also has been suggested to be written in Basque.

History and inscription

The age of the Sørup stone is uncertain, but it is thought to be from the period 1050–1250. The stone is made of granite and is approximately 2,14 meters tall, 75 cm broad and 22 cm thick. In written sources it is mentioned for the first time in 1589. In 1816 it was moved to Copenhagen, where it was placed by Rundetårn and later, in 1876, brought to the National Museum. Today it is not part of any exhibition, but is kept in the archive of the museum.

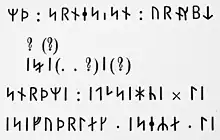

The Sørup runestone is decorated with a cross and an animal figure (possibly a lion) on the front, and has a runic inscription with some 50 runes, divided between two lines on the front and one line on one of the sides. Some of the runes are not found in the usual futhark and are thereby hard to interpret. Furthermore, there are two bind runes with uncertain reading order. Since parts of the stone are damaged, the reading is made even more difficult. A transliteration of the text can be:

Side A: m- : srnes-sn : urn=u=kb(h) | -a=si | s(n)rþmi : itcsih(k)i : li

Side B: isifuþrlak : iseya : li[3]

Non-lexical interpretation

The inscription of the Sørup stone is usually described as non-lexical, that is a text without semantic content. The runologist Ludvig Wimmer chose to make no transliteration of the signs of the Sørup stone in his book De danske runemindesmærker. Instead he only reproduced the appearance of the carvings, which has been interpreted to mean that he thought that the "text" itself did not have any meaning.[4] Bæksted imagined that the carvings could be made by a "skilful but illiterate travelling (judging by the ornament: Swedish) sculptor, who did not want to miss the commission for a monument with an inscription made by an as illiterate art-lover in Funen."[5] The web database Danske Runeindskrifter states that the Sørup stone "with its mixture of readable and dubious signs" gives "the impression of being a nonsensical inscription or an imitation of an inscription".[6]

The equal distribution between vowels and consonants has been used as an argument against the non-lexical interpretation. The longest consonant cluster of the inscription is s(n)rþm. If an illiterate person randomly would have carved 50 runes, it is likely that there would have been more and longer accumulations of either vowels or consonants.[7]

Cipher hypothesis

It has been suggested that the Sørup inscription is encrypted, but the deciphering attempts that have been under taken (for example replacing each sign with the next rune in the futhark) have not given any meaningful results. Another hypothesis is that the text is so heavily abbreviated that it is impossible to recreate.[8]

Nordic and Latin interpretations

The philologist Fr. Orluf read the inscription as a heavily abbreviated Latin text starting with a few words in Old Danish. He began on side B, where he translated isifuþrlak : iseʀa with "*Isifa's Þorlak in *Sera". The segment isifu would then be the genitive case of the unattested name *Isifa, while *Sera would be an old form of the toponym Sørup. Orluf interpreted the segments li, which are found in the end of two of the lines, as an abbreviation for libera nos 'redeem us'. Both the Danish and Latin parts of this interpretation have been rejected by other runologists.[9]

The linguist Rasmus Rask meant that it was possible to discern the Danish female name Signe at the end of side A, sih(k)i, but that the text otherwise was written in a grammatically corrupt language form.[10] Wimmer questioned whether it was possible to read any word at all in that segment, but meant that in that case it was more likely to be the verb signe "bless" than a name.[11]

Basque interpretation

Professor emeritus Stig Eliasson has suggested that the text could be written in Basque. Unlike a dozen other European languages that he has compared it to, the Basque structure showed many similarities with the text of the Sørup stone. Eliasson's reading is presented in the table below.[12]

| Text fragment | mþ | • | s | r | nes | .s | n | : | urn | u | k | b(h)… | is | a | … | | | snrþmi | : | itcsihķi | × | li | isifuþrl | a | k | • | iseya | • | li | ||

| Function or meaning | aff. | pret. 3rd pers. | non-pres. ind. | causative prefix | verb root | dative flag | 3rd pers. sing. dative | pret. ending | rune | proximal suffix | pl. | name? | patronymic suffix? | det.? | Ergative case ending? | husband + name? | surname | dative ending | name? | det. | ergative ending | aunt or *Izeba (name) | dative ending | |||||||

| Modern Basque equivalent | ba | z | e | ra | - | ts | o | n | errun | o | k | - | iz? | a? | k? | senar - | Etxehegi | ri | - - | a | k | izeba | ri |

With this analysis, the text would mean that someone (whose name is damaged; b(h)…isa…) let do/carve/cut (mþ•srnes.sn) these runes (urnuk) to her husband whose surname was Etxehegi (snrþmi : itcsihķi×li). On the side of the stone, an elliptical construction states that someone (isifuþrlak) did the same thing for his or her aunt or for someone with the unattested name Izeba (iseya•li).[13] The interpretation agrees with both Basque grammar and vocabulary, and with the semantic content of many other memorial commemorative formulas of the Viking Age. A commemorative formula is a genre typical for runic inscriptions, where someone (in this case b(h)…isa… and isifuþrlak) did something (runes) to someone's honour or memory (the husband Etxehegi and an aunt or Izeba respectively).[14] If the theory is correct it would mean that the oldest preserved relatively long text in Basque is kept in Denmark and is centuries older than the first book printed in Basque in year 1545.[15]

Within popular science, the interpretation has generated translations such as "Basa let cut these runes to her husband Etxehegi, and Isifus to his aunt Izeba".[16] However, parts of these translations, for example the names *Basa and *Isifus, do not find any support in Eliasson's articles. Neither does the part "aunt Izeba" has any foundation in the runic inscription, since iseya is either being interpreted as aunt or as a name, not as both.

Historic contacts between the Nordic countries and the Basque Country

A Basque reading of the Sørup stone presupposes Basque presence in Funen during the Middle Ages. However, there are no historical or archeological evidence for this, but in an appendix to his second article on the Sørup stone, Eliasson mentions some examples of Medieval connections between Northern and Southern Europe. Among other things, the discovery of 24 Spanish-Umayyad dirhams from around year 1000 at the island of Heligholmen outside of Gotland is mentioned. He also brings up the Vikings' capture of García Íñiguez of Pamplona in 861.[17] According to the American journalist Mark Kurlansky, Basque sailors reached the Faroe Islands already in 875.[18]

Critique

The reading has received mixed response. Apart from the difficulties that Eliasson brings up (for example the lack of a verb with the root *nes),[19] there are few objections to the morphological analysis. Hellberg states that "methodically, one cannot show that a text is nonsense without trying to exhaust the possibilities of other readings".[20] However, many reject the Basque reading on language-external grounds. For example, Quak writes that "even though Eliasson gives a precise and extensive foundation for his thesis, one still has difficulties with the assumption of such a distant foreign language in a Danish runic inscription."[21] At the web database Danske Runeindskrifter the interpretation is described as "rather speculative" "because of objective reasonableness criteria and the lack of comparative material".[22] Also Marco Bianchi, Ph.D. in Nordic languages, questions the "reasonableness of the assumption that a Basque inscription would show up in Funen".[23] Instead, Bianchi maintains that the inscription of the Sørup stone most likely is non-lexical and thereby an example of the fascination that people felt for writing in a society where the majority were illiterates.[24]

References

This article is based on the Swedish Wikipedia article Sørupstenen.

Notes

- ↑ Danske Runeindskrifter

- ↑ Wimmer (1898–1901:502).

- ↑ Danske Runeindskrifter Brackets indicate uncertain reading, while dashes represent damaged runes and equality signs represent bind runes. The rune c is a variant of the s rune. Colons and vertical bars are dividers.

- ↑ Danske Runeindskrifter Wimmer (1898–1901:502) himself did not explicitly state that the inscription is meaningless, but rather cautiously abstained from an interpretation and offered a suggestion "for the one who possibly will find the key to the interpretation of the inscription" (Danish original: "for den, som mulig en gang finder nøglen til indskriftens tolkning").

- ↑ Bæksted (1952:45f). Danish original: "en habil, men illitterær rejsende (efter ornamentikken at dømme: svensk) billedhugger, der ikke har villet gå glip af en lige så illitterær fynsk kunstelskers bestilling af et monument med indskrift."

- ↑ Danske Runeindskrifter Danish original: "Sørup-stenen giver med sin blanding af læselige og tvivlsomme tegn indtryk af af at være en nonsensindskrift eller indskriftimitation."

- ↑ Eliasson (2007:54–55 & 2010:57–59).

- ↑ Wimmer (1898–1901:500–502); Eliasson (2007:52–54).

- ↑ Jacobsen & Moltke (1941–1942); Eliasson (2010:51–53).

- ↑ Eliasson (2010:50–51).

- ↑ Wimmer (1989–1901:500).

- ↑ On the basis of Eliasson (2007:73). Brackets indicate uncertain reading, while three dots represent damaged runes. The runes .s and c are variants of the s rune, while ķ stands for a k rune turned upside down. Interpuncts, slashes and crosses are dividers.

- ↑ Basque kinship terms used as given names are, however, well attested in the Middle Ages, even though *Izeba does not happen to be attested as a name (Eliasson 2007:73).

- ↑ Eliasson (2007:73–76).

- ↑ Eliasson (2007:59).

- ↑ Runskrift får ny mening Olle Josephson in SvD, 2008-01-19 (read 2012-08-19). Swedish original: "Basa lät hugga dessa runor åt sin make Etxehegi, och Isifus åt sin faster Izeba."

- ↑ Eliasson (2010:74–75).

- ↑ Kurlansky (2000:58).

- ↑ Eliasson (2010:71–72).

- ↑ Hellberg (2007:226). Swedish original: "metodiskt kan man ju inte heller visa att en text är nonsens annat än genom att försöka uttömma möjligheterna av andra läsningar."

- ↑ Quak (2009:309). German original: "Obwohl Eliasson eine genaue und ausführliche Begründung für seine These gibt, hat man doch Schwierigkeiten mit der Annahme einer sehr entfernten Fremdsprache in einer dänische Runeninschrift."

- ↑ Danske Runeindskrifter. Danish original: "ret spekulativt" "på grund af saglige rimelighedskriterier og manglen på sammenligningsmateriale"

- ↑ Bianchi (2010:168). Swedish original: "rimligheten i antagandet att en baskisk inskrift skulle dyka upp på Fyn".

- ↑ Bianchi (2011).

Literature

- Bianchi, Marco (2010). Runor som resurs: Vikingatida skriftkultur i Uppland och Södermanland (Runrön. Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet, 20.) Uppsala: Institutionen för nordiska språk, Uppsala universitet.

- Bianchi, Marco (2011). Runinskrifter som inte betyder någonting Archived 2012-03-16 at the Wayback Machine. Sprogmuseet, 2011-05-12 (read 2012-08-19).

- Bæksted, Anders (1952). Målruner og troldruner. Runemagiske studier. (Nationalmuseets Skrifter, Arkæologisk-historisk Række, 4.) København: Gyldendalske Boghandel/Nordisk Forlag.

- Danske Runeindskrifter, web data base, containing photos of the Sørup monument.

- Eliasson, Stig (2007). 'The letters make no sense at all ...': Språklig struktur i en 'obegriplig' dansk runinskrift? In: Lennart Elmevik (ed.), Nya perspektiv inom nordisk språkhistoria. Föredrag hållna vid ett symposium i Uppsala 20–22 januari 2006, pp. 45–80. (Acta Academiae Regiae Gustavi Adolphi 97.) Uppsala: Kungl. Gustav Adolfs Akademien för svensk folkkultur.

- Eliasson, Stig (2010). Chance resemblances or true correspondences? On identifying the language of an ‘unintelligible’ Scandinavian runic inscription. In: Lars Johanson & Martine Robbeets (eds.), Transeurasian verbal morphology in a comparative perspective: Genealogy, contact, chance, pp. 43–79. (Turcologica 78.) Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. (Most of the article is available at Google Bücher.)

- Hellberg, Staffan (2007). "Nya perspektiv inom nordisk språkhistoria. Föredrag hållna vid ett symposium i Uppsala 20–22 januari 2006, red. av Lennart Elmevik. (Acta Academiae Regiae Gustavi Adolphi 97.) 208 s. Uppsala 2007. ISSN 0065-0897 ISBN 91-85352-69-1." Språk & stil: Tidskrift för svensk språkforskning 17, pp. 224–227.

- Jacobsen, Lis & Moltke, Erik (1941–1942). Danmarks runeindskrifter. København: Ejnar Munkgaards Forlag.

- Kurlansky, Mark (2000). The Basque History of the World. London: Vintage.

- Quak, Arend (2009). "Nya perspektiv inom nordisk språkhistoria. Föredrag hållna vid ett symposium i Uppsala 20–22 januari 2006. Utgivna av Lennart Elmevik. (Acta Academiae Regiae Gustavi Adolphi XCVII.) -Kungl. Gustav Adolfs Akademien, Uppsala 2007. 208 S. (ISBN 91-85352-69-1)." Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik 65, pp. 309–310. (The review is available at Google Bücher.)

- Wimmer, Ludvig (1898–1901). De danske runemindesmærker: Runstenene i Jylland og på øerne. København: Gyldendal.