| Sadko | |

|---|---|

| Tableau musical, or Musical picture | |

| Tone poem by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov | |

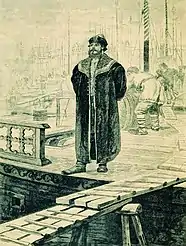

Sadko, painting by Ilya Repin (1876) | |

| Opus | 5 |

| Composed | 1867, revised 1869, 1892 |

| Performed | 1867 |

| Scoring | 3 (+picc), 2, 2, 2–4, 2, 2+bass, 1, timp, harp, strings |

Sadko, Op. 5, is a Tableau musical, or Musical picture, by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, written in 1867 and revised in 1869 and 1892. It is sometimes called the first symphonic poem written in Russia.[1] It was first performed in 1867 at a concert of the Russian Musical Society (RMS), conducted by Mily Balakirev.[2] Rimsky-Korsakov later wrote an opera of the same name which quotes freely from the earlier work.[3] From the tone poem the composer quoted its most memorable passages in the opera, including the opening theme of the swelling sea,[3] and other themes as leitmotifs[4] – he himself set out to "utilize for this opera the material of my symphonic poem, and, in any event, to make use of its motives as leading motives for the opera".[5]

Overview

Scenario

Sadko (Russian: Садко) was a legendary hero of a Russian bylina (a traditional East Slavic oral narrative poem). A merchant and gusli musician from Novgorod, he is transported to the realm of the Sea King. There, he is to provide music to accompany the dance at the marriage of the King's daughter. The dancing grows so frenzied that the surface of the sea billows and surges, threatening to founder the ships on it. To calm the sea, Sadko smashes his gusli. The storm dissipates and he reappears on the shore.

Composition

Mily Balakirev, leader of the Russian nationalist music group "The Five", was long fascinated with Anton Rubinstein's Europeanising Ocean Symphony and wanted to create a more specifically Russian alternative.[6] Music critic Vladimir Stasov suggested the legend of Sadko and wrote a program for this work,[6] giving it to Balakirev in 1861.[7] At first Balakirev relayed the program to Modest Mussorgsky, who did nothing with it.[8] (Mussorgsky's comment to Balakirev on hearing Rubinstein's Ocean Symphony was "Oh Ocean, oh puddle"; he had much preferred Rubinstein's conducting of the work over the work itself.[9]) Mussorgsky eventually offered the program to Rimsky-Korsakov, after he had long given up on it.[8] Balakirev agreed, counting on the naval officer's love of the sea to help him produce results.[6]

Instead of direct experience of the sea, Rimsky-Korsakov fell back on Franz Liszt's symphonic poem Ce qu'on entend sur la montagne for inspiration.[6] Acting as bookends to the middle of the work are two sketches of the calm, gently rippling sea.[6] While Rimsky-Korsakov took the harmonic and modulatory basis of these sections from the opening of Liszt's Montagne,[10] he admitted the chord passage closing these sections were purely his own.[11] The central section comprises music portraying Sadko's underwater journey, the feast of the Sea King and the Russian dance that leads the work to its climax.[6] Typical of Rimsky's modesty and self-criticism, he offers several influences for this section: Mikhail Glinka's Ruslan and Lyudmila, Balakirev's "Song of the Goldfish," Alexander Dargomyzhsky's Russalka and Liszt's Mephisto Waltz No. 1.[12] Rimsky-Korsakov chose the principal tonalities of the piece—a movement in D-flat major, the next in D major and then a return to D-flat major—specifically to please Balakirev, "who had an exclusive predilection for them in those days."[11]

Rimsky-Korsakov began the work in June 1867 during a three-week holiday at his brother's summer villa in Tervajoki, near Vyborg.[13] A month's naval cruise in the Gulf of Finland proved only a temporary interruption; by October 12, he was finished.[13] He wrote Mussorgsky that he was satisfied with it and that it was the best thing he had composed to date, but that he was weak from the intense strain of composition and needed to rest.[14]

Rimsky-Korsakov felt that several factors combined to make the piece a success—the originality of his task; the form that resulted; the freshness of the dance tune and the singing theme with its Russian characteristics; and the orchestration, "caught as by a miracle, despite my imposing ignorance in the realm of orchestration."[11] While he remained pleased with Sadko's form, Rimsky-Korsakov remained discontented with its brevity and sparseness, adding that writing the work in a broader format would have been more appropriate for Stasov's program.[11] He attributed this extreme conciseness to his lack of compositional experience.[11] Nevertheless, Balakirev was pleased with the work, paying Sadko a combination of patronization and encouraging admiration.[15] He conducted its premiere that December.[2]

Reaction

After an encore performance of Sadko at the Russian Musical Society (RMS) under Balakirev in 1868, one critic accused Rimsky-Korsakov of imitating Glinka's Kamarinskaya.[16] This reaction led Mussorgsky to create his magazine Classicist, in which he ridiculed the critic of the "rueful countenance."[16] At Balakirev's behest Rimsky-Korsakov revised the score for a November 1869 concert. Alexander Borodin wrote on the day of that concert, "In this new version, where many slips of orchestration have been righted and the former effects have been perfected, Sadko is a delight. The public greeted the piece enthusiastically and called Korsinka out three times."[17]

Subsequent history

In 1871, RMS program director Mikhail Azanchevsky had Sadko programmed as part of an effort to recruit its composer onto the faculty of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory.[18] (This was also the only time conductor Eduard Nápravník performed an orchestral work by Rimsky-Korsakov for the RMS. Four years later, Azanchevsky asked Nápravník several times to conduct the symphonic suite Antar. Nápravník finally refused, telling Azanchevsky with apparent disdain that Rimsky-Korsakov "might as well conduct it himself."[19])

In 1892, Rimsky-Korsakov reorchestrated Sadko.[20] This was the last of his early works that he revised.[20] "With this revision I settled accounts with the past," he wrote in his autobiography. "In this way, not a single larger work of mine of the period antedating May Night remained unrevised" (italics Rimsky-Korsakov).[20]

Rimsky-Korsakov conducted Sadko several times in Russia during his career, as well as in Brussels in March 1900.[21] Arthur Nikisch conducted it in the composer's presence in a Paris concert given in May 1907.[22]

Harmonic explorations

"The Five" had already been using chromatic harmony and the whole-tone scale before Rimsky-Korsakov composed Sadko.[23] Glinka had used the whole-tone scale in Ruslan and Lyudmila as the leitmotif of the evil dwarf Chernomor.[23] "The Five" continued using this "artificial" harmony as a musical code for the fantastic, for the demonic, and for black magic.[23] To this code Rimsky added the octatonic scale in Sadko.[24] This was a device he adapted from Liszt.[10] In it, semitones alternate with whole tones, and the harmonic functions are comparable to those of the whole-tone scale.[24] Once Rimsky-Korsakov discovered this functional parallel, he used the octatonic scale as an alternative to the whole-tone scale in the musical portrayal of fantastic subjects.[24] This held true not only for Sadko but later for his symphonic poem Skazka ("The Tale") and the many scenes depicting magical happenings in his fairy-tale operas.[24]

Instrumentation

Arrangements

In 1868, Rimsky-Korsakov's future wife Nadezhda Purgold arranged the original version of Sadko for piano four hands.[25] P. Jurgenson published this arrangement the following year, in conjunction with the orchestral score.[26]

References

- ↑ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 79 ft. 21.

- 1 2 Rimsky-Korsakov, 82

- 1 2 Taruskin, R. Sadko. In: The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Macmillan, London and New York, 1997.

- ↑ Abraham, Gerald. Rimsky Korsakov: A Short Biography. Duckworth, London, 1945, p96-97.

- ↑ Rimsky-Korsakoff NA. My Musical Life. translated from the Russian by J A Joffe. Martin Secker, London, 1924, p292.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Maes, Francis, tr. Pomerans, Arnold J. and Erica Pomerans, A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2002), 71.

- ↑ Rimsky-Korsakov, 74 ft. 10.

- 1 2 Rimsky-Korsakov, 74.

- ↑ Brown, David, Mussorgsky: His Life and Works (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 22

- 1 2 Rimsky-Korsakov, 78.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rimsky-Korsakov, 79.

- ↑ Rimsky-Korsakov, 78–79.

- 1 2 Calvocoressi, M.D. and Gerand Abraham, Masters of Russian Music (New York: Tudor Publishing Company, 1944), 350.

- ↑ Calvocoressi and Abraham, 350–351.

- ↑ Rimsky-Korsakov, 79–80.

- 1 2 Rimsky-Korsakov, 103.

- ↑ Rimsky-Korsakov, 109 ft. 26.

- ↑ Rimsky-Korsakov, 115–116.

- ↑ Rimsky-Korsakov, 156.

- 1 2 3 Rimsky-Korsakov, 312.

- ↑ Rimsky-Korsakov, 389–390.

- ↑ Rimsky-Korsakov, 434.

- 1 2 3 Maes, 83.

- 1 2 3 4 Maes, 84.

- ↑ Rimsky-Korsakov, 87.

- ↑ Rimsky-Korsakov, 109.