| Saint Helena scrub and woodlands | |

|---|---|

Cabbage trees on Saint Helena | |

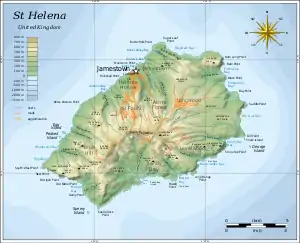

Map of Saint Helena | |

| Ecology | |

| Realm | Afrotropical |

| Biome | tropical and subtropical grasslands, savannas, and shrublands |

| Geography | |

| Area | 122 km2 (47 sq mi) |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Overseas territory | Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha |

| Coordinates | 15.95º S, 5.72º W |

| Conservation | |

| Conservation status | Critical/endangered[1] |

| Protected | 0 km2 (0%)[2] |

The Saint Helena scrub and woodlands ecoregion covers the volcanic island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean. The island's remote location gave rise to many endemic species. First discovered and settled in the 1500s, the island has been degraded by human activities. Most of its native habitat has been destroyed, and many of its unique plants and animals are extinct or endangered.[1]

Geography

Saint Helena is in the South Atlantic Ocean, 1,950 km west of the Angola on the African mainland.

The island is approximately 122 km2 in area. It is the eroded summit of a composite volcano, first formed by the Mid-Atlantic Ridge over 14 million years ago. Volcanic activity ceased about 6 million years ago.[3]

Millions of years of volcanic deposition and erosion have created coastal cliffs and dramatic landscape features. The island's year-round streams have eroded steep-sided valleys. Diana's Peak is the highest point on the island at 823 meters elevation.[1]

The island's capital and principal port is Jamestown. The island, together with Ascension Island to the northeast and Tristan da Cunha and Gough Island to the south, makes up the British Overseas territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha.

Climate

The climate of the island is dry and subtropical. Average monthly temperatures range from 15 to 32 °C. Mean annual rainfall is 152 mm, and higher in the island's windward hills.[1]

Flora

The island has about 45 species of native vascular plants. The genera Trochetiopsis, Nesohedyotis, Mellissia, Commidendrum, Melanodendron, Lachanodes, Pladaroxylon, and Petrobium are endemic.[3]

The middle elevations of the island were once covered with dry woodlands and forests. Principal trees included gumwood (Commidendrum robustum), bastard gumwood (Commidendrum rotundifolium), dwarf ebony (Trochetiopsis ebenus), and false gumwood (Commidendrum spurium). The Saint Helena olive (Nesiota elliptica) became extinct in the wild in 1994, and the last living specimen died in 2003. The native tree fern Dicksonia arborescens grows up to 3 metres high. The island is notable for native species in the composite family (Asteraceae). The composites are mostly herbaceous, but on St. Helena evolved woody into woody trees and shrubs. The native composite trees and shrubs include species of Pladaroxylon, Lachanodes, Commidendrum, Melanodendron, and Petrobium.[3]

Native plants are now limited to a few sheltered and inaccessible locations, including a small gumwood stand at Peak Dale. Prosperous Bay Plain is a 150-hectare semi-desert area which is home to the native shrub Suaeda fruticosa, the endemic annual plant Hydrodea cryptantha, most of the remaining habitat of the endemic barn fern (Asplenium haughtonii), along with many endemic invertebrates, some of which are known only from this location. A portion of the plain was destroyed to build Saint Helena Airport.[1]

The present-day vegetation of the island is mostly of naturalized non-native plants. Approximately 260 species of non-native plants are now naturalized on the island. Over half the island is covered by wasteland of bare soil and sparse scrub of mostly exotic plants. Other areas are covered with pasture and abandoned flax plantations. Regenerating shrubland and woodland includes many exotic species, with prickly pear (Opuntia ficus-indica), common lantana (Lantana camara), Brazilian pepper tree (Schinus terebinthifolia), Chrysanthemoides monilifera, Bermuda cedar (Juniperus bermudiana), green-aloe (Furcraea gigantea), maritime pine (Pinus pinaster), cape cheesewood (Pittosporum viridiflorum), iceplant (Carpobrotus edulis), yellow trumpetbush (Tecoma stans), and wattle (Acacia longifolia) prominent. The Millennium Forest, on the east side of the island, is a 250-hectare reserve where thousands of native trees have been replanted.[1]

Fauna

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

The Saint Helena plover or wirebird (Charadrius sanctaehelenae) is the island's sole surviving endemic bird species. It is found on interior pasturelands and the Prosperous Bay Plain's shrublands.[1]

Fossil and subfossil remains of several extinct land birds have been found on the island – the Saint Helena rail (Aphanocrex podarces), Saint Helena crake (Zapornia astrictocarpus), Saint Helena dove (Dysmoropelia dekarchikos), Saint Helena cuckoo (Nannococcyx psix), and Saint Helena hoopoe (Upupa antaios). Most are thought to have been present when the first human settlers arrived there.[1][3]

The islands have no known native mammals, amphibians, or terrestrial reptiles. There are many native and endemic invertebrates. 157 endemic beetles have been recorded, including the endangered ground beetle Aplothorax burchelli.[1] The giant Saint Helena earwig (Labidura herculeana) is likely extinct.

History

The island was discovered by Portuguese navigator João da Nova in May 1502, close to the feast day for St. Helena. Goats were introduced soon afterwards to provide food for passing ships. In 1588 the English seacaptain Thomas Cavendish visited the island, and discovered large herds of goats. It soon became a port of call for vessels traveling between Europe and ports on the Indian Ocean. In 1659 the East India Company claimed control of the island and established a fort and settlement near the site of present-day Jamestown. The island's first inhabitants were English traders and settlers, along with slaves from South and Southeast Asia and Madagascar. In 1673 nearly half of the island's inhabitants were slaves. The island's slaves were emancipated between 1826 and 1836.[1]

In 1659 the woodlands were fragmented by overgrazing, although large wooded areas still remained, including the Great Wood on the northeastern corner of the island. Portions of the island were cleared for agriculture, including orchards and fields, and native woodlands harvested for timber and firewood. Pigs, sheep, and cattle were also introduced to the island.[1]

In 1709 Governor Roberts reported to the East India Company's Court of Directors that the island's native timber, notably the endemic Saint Helena ebony (Trochetiopsis ebenus) was rapidly disappearing, and recommended limiting the grazing of goats on the island. The Directors refused to order the goats' removal.[4]

Between 1723 and 1727 a stone wall was constructed around a remnant of the Great Wood to protect it from grazing cattle, goats, and timber harvesting. The Great Wood Wall enclosed 6 km2, but proved ineffective in protecting the wood. The wood was mostly cleared of trees, and maintenance of the wall was abandoned.[4]

Napoleon was exiled to St. Helena from 1815 to 1821. Other prisoners exiled there included Zulu warriors after the Anglo-Zulu War in the 1870s, and Boer prisoners during the Boer Wars at the end of the 19th century.[1]

By the 19th century the native woodlands had mostly disappeared. Plantations of New Zealand flax (Phormium tenax) were established after 1900 to produce fiber for string and rope. Demand for flax fiber collapsed in the 1960s, and most of the flax plantations were abandoned.[1]

Conservation and threats

Most of the wild habitat on the island has been lost to overgrazing, conversion to pasture and agriculture, and introduced species. Some interior areas are still covered in New Zealand flax.[1]

A portion of the Prosperous Bay Plain's native shrublands were displaced by construction of Saint Helena Airport between 2012 and 2016.[1]

Protected areas

Peaks National Park was created in 1996, and protects 81 hectares on the central ridge of the island, including the island's three highest peaks, Diana's Peak, Cuckold Point, and Mount Actaeon. The park protects forests of black cabbage tree (Melanodendron integrifolium) and other native plants. The park has an endemic plant nursery that propagates island native plants.

In 2000 the Millennium Forest project was initiated. It involves reforesting a denuded area on the eastern side of the island with native trees, to restore a portion of the Great Wood which once covered the middle of the island. About 250 hectares have been planted with thousands of gumwood and other native trees.[5]

See also

External links

- "St. Helena scrub and woodlands". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "St. Helena scrub and woodlands". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- ↑ Dinerstein, Eric; Olson, David; et al. (June 2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) Supplemental material 2 table S1b. - 1 2 3 4 Cronk, Q. C. B. (1987). "The History of Endemic Flora of St Helena: A Relictual Series". New Phytologist Volume 105, Issue 3, March 1987, Pages 509-520. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.1987.tb00888.x

- 1 2 "The Great Wood Wall". Saint Helena Island Info. Accessed 3 November 2020.

- ↑ "Millennium Forest". StHelenaIsland.info. Accessed 3 November 2020.