Saint Melangell of Powys | |

|---|---|

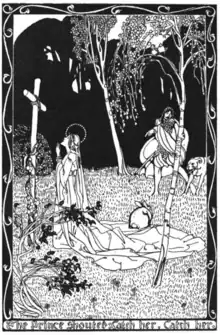

Illustration of Melangell and the hare (1907) | |

| Abbess, Hermit | |

| Born | Ireland |

| Died | Kingdom of Powys, Wales |

| Venerated in | |

| Major shrine | Saint Melangell's Church, Pennant Melangell |

| Feast | 27 May or 31 January |

| Patronage | Hares |

Melangell (Latin: Monacella) was a Welsh hermit and abbess. She possibly lived in the 7th or 8th century, although the precise dates are uncertain. According to her hagiography, she was originally an Irish princess who fled an arranged marriage and became a consecrated virgin in the wilderness of the Kingdom of Powys. She supernaturally protected a hare from a prince's hunting dogs, and was granted land to found a sanctuary and convent.

Melangell's cult has been closely centered around her 12th-century shrine at St Melangell's Church, Pennant Melangell, which was founded at her grave. The church contains the reconstructed Romanesque shrine to Melangell, which had been dismantled in the aftermath of the Reformation. Since the medieval period, she has been venerated as the patron saint of hares; for many centuries, her association with hares was so strong that locals would not kill a hare in the parish of Pennant Melangell.

Life

Melangell's primary hagiography is the Historia Divae Monacellae, written in the 15th century. The Historia survives in three complete and two incomplete manuscripts, with the earliest dating from the late 16th century, along with one printed copy of a 17th-century manuscript.[1] Melangell's chronology is unknown, with some evidence pointing to the 7th or 8th century.[2] Although the Historia gives a date of 604 AD, this date is suspect due to its likely origin in Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica, which is viewed as historically unreliable by scholars.[3] Iolo Morganwg and David Daven Jones list Melangell as a relative or descendant of Roman emperor Macsen Wledig,[4][5] although this is not mentioned in her hagiography.

Jane Cartwright, a professor at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David, draws a parallel between Melangell's hagiography and Welsh apocryphal legends about Mary Magdalene; both having become penitents deep in the woods and not seeing men for many years. In their respective tales, men who attempt to approach them in the wilderness are struck by their divinity.[6]

Hagiographical account

The Historia depicts Melangell's life with heavy emphasis on her virginity, placing it as the essence of her sanctity.[7] A lesson that the narrative puts forth is that divine retribution awaits those who attempt to violate a virgin, a moral also found in the hagiography of Winefride and legends surrounding other Welsh virgin martyrs.[8]

According to the Historia, Melangell was a princess of Ireland who fled an arranged marriage. She lived in the wilderness of Powys as a consecrated virgin for fifteen years before being discovered by a prince by the name of Brochwel Ysgithrog. In 604 AD, Brochwel was hunting near Pennant (now Pennant Melangell). His dogs, chasing a hare, led him to a "virgin beautiful in appearance" devoutly praying,[9] with the hare lying safe under the hem of her dress. The prince urged the dogs on, but they retreated and fled from the hare. After hearing Melangell's story, Brochwel donated the land to her, granting perpetual asylum to both the people and animals of the area. Melangell lived for another 37 years in the same place, founding and becoming abbess of a community of nuns. The hares and wild animals behaved towards Melangell as if they were tamed, and miracles were attributed to them. After Melangell's death, someone by the name of Elise attempted to attack the virgins, but "came to an end most wretchedly and perished suddenly."[9]

Veneration

Melangell and Winefride are the only two Welsh female saints to have Latin hagiographies.[2] Melangell's cult likely flourished locally for centuries before the Historia was written; the Romanesque shrine and church built over her grave indicate that her cult had become established in Pennant Melangell by the 12th century, with her grave being a subject of veneration since before the Norman conquest of Wales.[10] Melangell's feast day is 27 May[2] or 31 January.[11][12]

Aside from her shrine at Pennant Melangell, the saint also has a Western Orthodox parish dedicated to her in Benchill, Greater Manchester. The congregation, founded in 2018 as part of the independent Orthodox Church of the Gauls, meets in an Anglican parish church.[13]

Association with hares

Welsh antiquarian Thomas Pennant, in his 1810 work Tours in Wales, describes Melangell's association with hares, noting that they were nicknamed "St Monacella's lambs" (Welsh: Wyn Melangell).[14][15] Pennant also remarks that "till the last century, so strong a superstition prevaled [sic], that no person would kill a hare in the parish; and even later, when a hare was pursued by dogs, it was firmly believed, that if anyone cried 'God and St. Monacella be with thee,' it was sure to escape."[14] As late as the year 1900, the locals of Pennant Melangell were noted for their refusal to kill hares.[16] Archaeologist Caroline Malim posits a connection between the local veneration of hares (along with other local traditions) and pre-Christian Celtic religion, noting that hares have historically been associated with the moon goddess in mythologies around the world.[17]

Shrine at Pennant Melangell

The settlement of Pennant itself was likely an 8th-century foundation, and the earliest part of the church dates to the 12th century. At the east end of the church, behind the chancel, is a small chamber known as the cell-y-bedd (cell of the grave), which housed the original shrine. The grave was that of Melangell, and it would have served as a reliquary, displaying her remains for visiting pilgrims.[18] The ornate Romanesque carving on the shrine, now located in the chancel, is characteristic of local work of the late 12th century.[19]

In the Reformation period and the centuries afterwards, the cell was turned into a schoolroom and the shrine was dismantled. The sculptured stones of the shrine were reused in the walls of the church and in the lychgate.[20] In 1958, restoration work was undertaken on the church, which included reconstructing the shrine in its original location, the cell-y-bedd. In 1991, the reconstructed shrine was moved to its present location in the chancel.[21]

Melangell is also represented in an effigy traditionally identified as the saint, and in the carved rood screen. The effigy depicts a woman wearing 14th-century clothing, with animals (possibly hares) at her feet. If the animals are indeed hares, then it would likely be a cult effigy to Melangell, similar to those found at St Pabo's Church, Llanbabo and St Iestyn's Church, Llaniestyn. The late 15th-century rood screen illustrates the story of Melangell and the hare.[22]

In literature

Agnes Stonehewer published a long poem about Melangell in 1876.[23] Another poem about Melangell was published in the poetry journal Agenda in 2014.[24]

The story of Melangell and the hare has appeared in compilations of Welsh fairy tales. William Jenkyn Thomas's 1907 The Welsh Fairy Book[25] and William Elliot Griffis' 1921 Welsh Fairy Tales[26] both include short stories about Melangell's encounter with the prince.

See also

- Ann Griffiths, a Welsh hymn-writer and poet from Llanfihangel-yng-Ngwynfa, near Pennant Melangell

References

Citations

- ↑ Pryce 1994, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 Farmer, David (2011). Oxford Dictionary of Saints (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-19-959660-7.

- ↑ Ralegh Radford & Hemp 1959, p. 83.

- ↑ Price, Thomas (1848). Iolo Manuscripts: A Selection of Ancient Welsh Manuscripts, in Prose and Verse, from the Collection Made by the Late Edward Williams, Iolo Morganwg, for the Purpose of Forming a Continuation of the Myfyrian Archaiology. W. Rees; sold by Longman and Company, London. pp. 512–513.

- ↑ Jones, David Daven (1910). The Cymry and their church. Carmarthen: W. Spurrell. p. 76.

- ↑ Cartwright, Jane (2013). Mary Magdalene and Her Sister Martha: An Edition and Translation of the Medieval Welsh Lives. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0-8132-2189-2 – via Project MUSE.

- ↑ Pryce 1994, p. 23.

- ↑ Cartwright, Jane (2002). "Dead Virgins: Feminine Sanctity in Medieval Wales". Medium Ævum. 71 (1): 7. doi:10.2307/43630386. ISSN 0025-8385. JSTOR 43630386 – via JSTOR.

The message put forth in the Historia is crystal clear. Anyone who attempts to violate one of Christ's virgins risks divine retribution. Those who threaten or harm the female saints are frequently cursed, swallowed up by the earth, melted, frozen, or suffer excruciating sudden death. In the Vite sancte Wenefrede, for instance, Beuno curses Gwenfrewy's murderer, who immediately melts and disintegrates.

- 1 2 Pryce 1994, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Pryce 1994, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ The Book of saints; a dictionary of servants of God canonised by the Catholic church; extracted from the Roman & other martyrologies. Compiled by the Benedictine monks of St. Augustine's Abbey, Ramsgate (3rd ed.). New York City: The Macmillan Company. 1934. p. 192.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Bond, Andrew; Mabin, Nicholas (1979). Saints of the British Isles. Bognor Regis, West Sussex: New Horizon. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-86116-211-6.

- ↑ "Saint Melangell's Orthodox Church". www.orthodoxmanchester.org.uk. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- 1 2 Pennant, Thomas (1810). Tours in Wales. Vol. 3. Wilkie and Robinson. p. 174.

- ↑ Pryce 1994, p. 35.

- ↑ Thomas, N. W. (1900). "Animal Superstitions and Totemism". Folklore. 11 (3): 239–240. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1900.9719953. JSTOR 1253113 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Malim, Caroline (2018). "As Above, So Below: St Melangell and the Celestial Journey". In Gheorghiu, Dragoş; Nash, George; Bender, Herman; Pásztor, Emília (eds.). Lands of the Shamans: Archaeology, Landscape and Cosmology. Oxbow Books. p. 98. doi:10.2307/j.ctvh1dx1b.8. ISBN 978-1-78570-954-8. JSTOR j.ctvh1dx1b – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Ralegh Radford & Hemp 1959, pp. 85–88.

- ↑ Ralegh Radford & Hemp 1959, p. 93.

- ↑ Ralegh Radford & Hemp 1959, pp. 89–91.

- ↑ Britnell, W.J.; Watson, K. (1994). "Saint Melangell's Shrine, Pennant Melangell". Montgomeryshire Collections. 82: 148. hdl:10107/1271085 – via National Library of Wales.

- ↑ Ridgeway, Maurice H. (1994). "Furnishings and Fittings in Pennant Melangell Church". Montgomeryshire Collections. 82: 130–135. hdl:10107/1271085 – via National Library of Wales.

- ↑ Stonehewer, Agnes (1876). Monacella: A Poem. London: H.S. King & Co.

- ↑ Lewis, Anna (March 2014). "Melangell". Agenda. 48 (1–2): 78.

- ↑ Thomas, William Jenkyn (1907). The Welsh Fairy Book. T.F. Unwin. ISBN 978-7-250-00548-1.

- ↑ Griffis, William Elliot (1921). "Welsh Rabbit and Hunted Hares". Welsh Fairy Tales. Project Gutenberg.

Bibliography

- Pryce, Huw (1994). "A New Edition of Historia Divinae Monacellae". Montgomeryshire Collections. 82: 23–40. hdl:10107/1271085 – via National Library of Wales.

- Ralegh Radford, C.A.; Hemp, W.J. (1959). "Pennant Melangell: The Church and the Shrine". Archaeologia Cambrensis. 108: 81–113. hdl:10107/4742843 – via National Library of Wales.

Further reading

- Keulemans, Michael; Burton, Lewis (2006). "Sacred place and pilgrimage: modern visitors to the shrine of St Melangell". Rural Theology. Taylor & Francis. 4 (2): 99–110. doi:10.1179/rut_2006_4_2_003. S2CID 192090558. (available with The Wikipedia Library)

- Siôn, Tania ap (2020). "The Power of Place: Listening to Visitors' Prayers Left in a Shrine in Rural Wales". Rural Theology. Taylor & Francis. 18 (2): 87–100. doi:10.1080/14704994.2020.1771904. S2CID 219434607. (available with The Wikipedia Library)