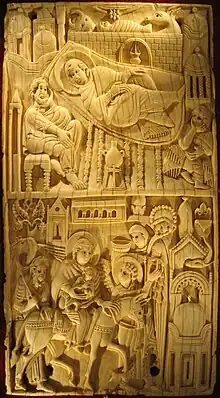

The Salerno Ivories are a collection of Biblical ivory plaques from around the 11th or 12th century that contain elements of Early Christian, Byzantine, and Islamic art as well as influences from Western Romanesque and Anglo-Saxon art.[1] Disputed in number, it is said there are between 38 and 70 plaques that comprise the collection.[2] It is the largest unified set of ivory carvings preserved from the pre-Gothic Middle Ages, and depicts narrative scenes from both the Old and New Testaments.[3] Some researchers believe the Ivories hold political significance and serve as commentary on the Investiture Controversy through their iconographies. The majority of the plaques are housed in the Diocesan Museum of the Cathedral of Salerno, which is where the group's main namesake comes from. It is supposed the ivories originated in either Salerno and Amalfi, which both contain identified ivory workshops, however neither has been definitively linked to the plaques so the city of origin remains unknown. Smaller groups of the plaques and fragments of panels are currently housed in different museum collections in Europe and America, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Louvre in Paris, the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, the Hamburg Museum of Art and Trade, and the Sculpture Collection in the Berlin State Museums.[4][5]

Historical background and ivory

The earliest documentation of the ivories was in the inventories of the Salerno Cathedral during the early sixteenth century.[1] A lack of further written sources causes debate over when and where the ivories were carved, who commissioned them, the arrangement of the panels, and the geographical and cultural origins of the artists.[1] The plaques make up one part of a broad group of ivory artifacts from the same era and region of southern Italy. These consist of collections of objects such as oliphants, bone-and-ivory boxes, chess pieces, Siculo-Arabic boxes, Italo-Byzantine ivories the Farfa Casket, and the Grado Chair ivory series.[6] The dating of the ivories spans from the later eleventh to the mid twelfth century.[7] The original sequence and arrangement for the ivories are unknown.[7] Scholars have proposed the plaques were part of a throne, casket or door, but no evidence has been found to support this.[2] The only documentation discussing an arrangement order for the plaques was at the death of the Archbishop of the Cathedral Lucio Sanseverino in 1623, when he requested them hung on an altar at the cathedral.[7]

While the exact origins are unknown, popular theory suggests that they originated from the Campanian region of Italy opposed to Salerno or Amalfi.[2] The plaques are similar to Sicilian mosaic images found within the Cappella Palatina at Palermo as well as the Cathedral of Monreale.[2] Additionally, this structure is a mix of Fatimid, Norman, and Byzantine styles, which reveals the expansive connections Italy had within the time.[2] These connections are also seen in Amalfi, where the plaques were created.[2] Their relationship with Muslim trade partners connected Italian traders to Egypt and African trade routes.[2] The panels originating from workshops in 12th century Sicily or Levant have been considered along with the Norman court or affiliated with possible monastic bonds.[2]

Another possibility is that they were commissioned by the Archbishop Alfanus after the consecration of the Salerno Cathedral in the last quarter of the eleventh century.[3] Alfanus has been connected with the making of a similar cycle at Monte Cassino.[3] Another theory is that the panels were ordered by the Archbishop of Salerno, William of Ravenna, around 1140 for the refurbishing of the cathedral's altar, an event that was documented in 1137.[1]

Description

It is disputed that there are between 38 and 70 figurative plaques, thirteen medallions, and seventeen border carving fragments.[2][8] The majority of the Salerno Ivory panels are well-preserved and in excellent condition.[3] They are carved in relief into flat segments of ivory. There are eighteen plaques that depict scenes from the Old Testament.[9][10] These plaques are on average 12 cm to 24 cm wide and about 9 cm tall, while many of the New Testament plaques average 24 cm tall and 12 cm wide.[3] Cornices and borders average from 21 to 25 cm long by about 7 cm wide.[11] The supporting columns are about 23 cm by 2 cm and the busts are 6 cm squared.[11] Most of the plaques are divided into an upper half and lower half and contain two separate scenes, with a few exceptions.[3][2] The plaques that depict the Old Testament are oriented horizontally, whereas the plaques that depict the New Testament are oriented vertically.[3]

The plaques illustrate a comprehensive linear narrative of the life of Christ and the most important phases of his life, from his birth and infancy to his Resurrection.[3] The Old Testament series of plaques contains a series of scenes beginning with Creation (pictured at top of page) and then recounting the stories of Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Moses, ending with Moses Receiving the Laws.[3][8] The New Testament series includes scenes such as Healing of the Blind and Lame, Christ Appears at Lake Tiberias, and Mary’s Announcement of the Resurrection to the Apostles.[3] Unlike other late medieval works where episodes from the Old and New Testaments were illustrated side by side, the two Testaments appear on separate plaques in the Salerno Ivories.[3]

Each plaque is carved in high relief, with figures, objects and animals in the scene appearing to come out of the ivory panel.[12] Some of the different figures have glass eyes still intact in colors like blue, black or red.[12] Each scene is bordered around the edges of the ivory and the entire series has detached decorative cornices, borders and colonnettes.[12] The cornices and borders contain inhabited scrolls, plants and cornucopias, while the colonnettes contain a decorative twisting column.[12] There are also small square-and-circle bust portraits of different Apostles and Donors.[12]

Scholars use manuscript illustrations and contemporary ivory monuments as sources for the iconography of the Salerno Ivories.[8] These sources include a sixth century manuscript; Cotton Genesis, Middle Byzantine Octateuch, Grado Chair Ivories, and the Farfa Casket, all of which give a profound stylistic influence on the Salerno Ivories.[3]

Iconographic anomalies

Researchers have found that the Salerno Ivories contain several iconographic anomalies related to Old Testament scenes.[2] These iconographies are considered anomalies due to their unusual imagery and the way in which they stray from usual Old Testament scenes.[2] Typical Old Testament scenes such as those found in the frescos in Sicilian churches at both Monreale and Palermo can be attributed to the Cotton Genesis.[2] However, the Salerno Ivories include scenes that are mostly unexplained.[2] Moreover, there is an illustration derived from Genesis 1:2-5 with spheres entitled ‘Lux’ and ‘Nox,’ another scene of Noah creating an oddly shaped ark, and lastly a depiction of Abraham and God together at an altar.[2] The most interesting of all happens to be a plaque exhibiting the creation of the sun, moon, and stars.[2] Although this scene has a decent amount in common with other Genesis cycles, it still differs significantly from traditional Old Testament depictions.[2]

Significance

Political significance

The Salerno Ivories were thought to be created in the late 11th century when the Normans in Italy were uniting principalities under different authorities.[8]

The Ivories are primarily understood as Christian religious works, but some scholars have also proposed they held a political significance as well.[8] While there is a lack of documentary evidence that explicitly suggests the political message behind the ivories, some researchers believe that the political message lies within the panels themselves.[8] Several aspects of the Old Testaments cycle, such as themes of covenant and iconographic anomalies, may point to the events of the Investiture Controversy which is relevant to the Salerno Ivories’ chronology.[2][8]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Müller, Kathrin. “OLD AND NEW. Divine Revelation in the Salerno Ivories.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz, vol. 54, no. 1, 2010, pp. 1–30. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41414763.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Corey, Elizabeth C. "The Two Great Lights: Regnum And Sacerdotium In The Salerno Ivories." History of Political Thought 34, no. 1, pg. 3, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Bergman, Robert P. The Salerno Ivories : Ars Sacra from Medieval Amalfi. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, pgs.1-2, 1980.

- ↑ Tomasi, Michele (July 2016). "The Salerno Ivories. Objects, Histories, Contexts, Francesca Dell'Acqua, Anthony Cutler, Herbert L. Kessler, Avinoam Shalem, Gerhard Wolf eds, Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag 2016". Convivium. 3 (2): 174–179. doi:10.1484/j.convi.4.000024. ISSN 2336-3452.

- ↑ God the Father and Abraham (inventory number 5952)

- ↑ Bergman, Robert P. (1980-12-31). The Salerno Ivories. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674188235. ISBN 9780674188228.

- 1 2 3 Dell’Acqua, Francesca. The Salerno Ivories: Objects, Histories, Contexts. Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, pg. 211, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Corey, Elizabeth C. "The Purposeful Patron: Political Covenant In The Salerno Ivories." Viator: Medieval And Renaissance Studies, Vol 40, No 2, pg. 55, 2009.

- ↑ Eastmond, The Salerno Ivories: Objects, Histories, Contexts. Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, pgs.99, 97-109, 103-106, 2016.

- ↑ Wixom, William D. "Eleven Additions to the Medieval Collection." The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 66, no. 3, pg. 87-9, 1979.

- 1 2 Kunsthistorisches Institut, Max-Planck-Institut, Iparmüvészeti Múzeum, The Metropolitan Museum, Francesca Dell’Acqua, Foto Scala, Firenze/bpk, Bildagentur für Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte, Museum für Kunst and Gewerbe, pg. 329-38, 339-354. The Salerno Ivories: Objects, Histories, Contexts. Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Museo Diocesano The Salerno Ivories: Objects, Histories, Contexts. Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, pgs. 28-54, 355; 2015.