Sam Steiger | |

|---|---|

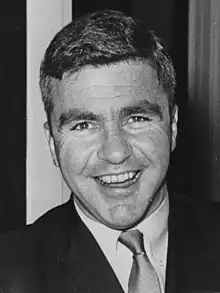

Steiger in November 1973 | |

| Mayor of Prescott, Arizona | |

| In office November 23, 1999 – November 21, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Paul Daly |

| Succeeded by | Rowle Simmons |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Arizona's 3rd district | |

| In office January 3, 1967 – January 3, 1977 | |

| Preceded by | George F. Senner Jr. |

| Succeeded by | Bob Stump |

| Member of the Arizona Senate from the Yavapai County district | |

| In office January 1, 1961 – January 1, 1965 Serving with David H. Palmer | |

| Preceded by | Charles H. Orme Sr. |

| Succeeded by | Boyd Tenney |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Samuel Steiger March 10, 1929 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | September 26, 2012 (aged 83) Prescott, Arizona, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Other political affiliations | Libertarian |

| Alma mater | Colorado A&M |

| Occupation | Rancher |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Battles/wars | Korean War |

| Awards | Silver Star Purple Heart |

Samuel Steiger (March 10, 1929 – September 26, 2012) was an American politician, journalist, political pundit. He served five terms as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, two terms in the Arizona State Senate, and one term as mayor of Prescott, Arizona. Steiger also made an unsuccessful run for the U.S. Senate, served as a special assistant to Arizona Governor Evan Mecham, and hosted political talk shows on both radio and television. Despite these accomplishments, Steiger is best known for two incidents: The first, while he was a sitting Congressman, was the 1975 killing of two burros. The second was painting a crosswalk between Prescott's courthouse and nearby Whiskey Row.

Early life

Steiger was born March 10, 1929, in New York City to Lewis and Rebecca (Klein) Steiger.[1] He was educated in local schools before attending college.[2] His first trip to Arizona occurred at age 14 when he visited a dude ranch.[3] Steiger attended Cornell University before graduating in 1950 with a Bachelor of Science from Colorado A&M.[4]

Following college, Steiger was commissioned into the United States Army. Serving during the Korean War as a tank platoon leader, he was awarded the Purple Heart for his actions.[5] After leaving the army, Steiger settled in Prescott, Arizona.[2]

Steiger married his first wife, Cynthia Jean Gardner, in 1954. The couple had three children: twins Lewis and Gail in April 1956, followed by Delia Rebecca in May 1959.[1] His first marriage would end in divorce, as would Steiger's marriage to his second wife, Lynda, in January 1979.[6]

Legislative career

In 1959, Steiger entered politics on a wager. While working as a ranch hand in Springerville, he and several friends observed that Yavapai County had never elected a Republican representative. Steiger theorized that this was because the right Republican had not yet run for office. His friends challenged him to run for office and in 1960 Steiger was elected to the Arizona State Senate.[3] While a freshman senator he wrote a column claiming that other members of the legislature had sold their votes for money and challenged senate leaders over perceived backroom deals.[7][8] Steiger also likened himself to a tiger and used a black and orange motif on his campaign signs.[9]

After two terms in the statehouse, in 1964, Steiger ran against incumbent George F. Senner, Jr. for Arizona's 3rd district seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. He was endorsed by all the newspapers within the district,[10] with the Arizona Republic saying "Sam is independent, friendly, quick-witted, very out-spoken, crazy over horses, and wears an infectious smile".[9] Despite these endorsements, Steiger lost a close election.[11] He then served as a correspondent on the Vietnam War before making a second run for the congressional seat in 1966.[12] Benefiting from a mid-decade reapportionment which pushed the district into a heavily Republican section of Maricopa County, near Phoenix, as well as Democratic voters defecting to other party candidates, Steiger defeated Senner on his second attempt.[13][14]

As a congressman, Steiger continued his outspoken ways. During his first term he delivered a speech from the floor of the House claiming it is "an irrefutable fact of life that the elected official is regarded by those who elect him as capable of the most flagrant dishonor," and calling for a "code of ethics" which included "full disclosure of assets, liabilities, honorariums, etc., by members, their spouses, and staff members."[9] Steiger would later claim a number of his colleagues were frequently drunk and that "there are members of Congress you wouldn't hire to wheel a wheelbarrow."[15] As a result of these comments, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall, previously an Arizona congressman himself, labeled Steiger as "a bomb thrower".[16]

Steiger's voting record in the House was staunchly conservative, earning him, in 1974, a zero rating Americans for Democratic Action and a 100% rating from Americans for Constitutional Action.[17] Additionally, the congressman won a Distinguished Service Award from Americans for Constitutional Action for his "devotion to those fundamental principles of good government which serve to promote individual rights and responsibilities, a sound dollar, a growing economy, and a desire for victory over communist aggression."[18] His opposition to legislation favored by conservationists earned him membership to the League of Conservation Voters's "Dirty Dozen" list.[19] These efforts included Steiger's opposition to controls on strip mining and support of coal companies.[17]

Steiger was very popular at home. He only faced one close reelection contest, in 1974. That year, he only held onto office by 3,073 votes. He only survived due to a 3,291-vote margin in the district's share of Maricopa County, which had as many people as the rest of the district combined.[20] A number of Republicans were either defeated or faced tight races due to voter anger at the Watergate Scandal.

Burro shooting

A defining moment for Steiger came in 1975. A herd of about 150 burros had been running loose near Paulden, scaring children at bus stops and causing the Congressman to receive numerous complaints.[9] On August 9, 1975, Steiger went to investigate the complaints and found a group of 14 burros that had been placed in an enclosure along a highway, until their owner could come to claim them. Entering the enclosure with a .30 caliber carbine, the Congressman went to check the animals' brands to determine who owned them. In a report to the local sheriff, Steiger later claimed the burros charged him and he shot the two lead animals in self-defense.[21] The incident was forwarded to the county attorney's office for consideration before the burros' owner brought a pair of civil suits against Steiger.[22][23]

In addition to the official investigation of the incident, Steiger suffered other repercussions. Children picketed outside Phoenix's federal building, carrying signs reading "Steiger joins the murderers of innocent animals", and the once political tiger was re-branded "the jackass killer."[9] The Congressman later observed, "I could find a cure for cancer and they'd remember me as the guy who shot the burros."[24]

U.S. Senate run

In 1976, Steiger decided to run for the U.S. Senate seat opened up by Paul Fannin's retirement. His opponent during the Republican primary was fellow congressman John Bertrand Conlan. The campaign between the two congressmen became ugly with Conlan saying "We are both conservatives, but our style is different. He uses a meat ax and I use a scalpel"[25] and asking voters if they desired "a Jew from New York telling Arizona what to do".[9] Steiger countered with "John thinks of himself as a scalpel. I prefer to think of him as a Roto-Rooter,"[25] and claiming "Godzilla would make a better Senator than John Conlan."[9]

Steiger defeated Conlan in a tight race, but the effects of the primary left him severely wounded in the general election. Many of Conlan's supporters abandoned their party's candidate and instead supported Democratic Pima County Attorney Dennis DeConcini.[26] In the November 2 election, Steiger lost to DeConcini, 43–54%.[27]

Following his unsuccessful run for the U.S. Senate, Steiger attempted to return to the Arizona State Senate in 1978.[28] This was followed in 1982 with him running for governor as a member of the Libertarian Party. His goal during the campaign was to obtain five percent of the vote and establish ballot access for the Libertarian party.[29] He succeeded with 5.1% of the vote, the fourth-best result for any Libertarian gubernatorial candidate.[30] During this time, Steiger saw a steady erosion of his approval. As Prescott Councilman Ken Bennett explained, Steiger was popular in his hometown as a "brash young congressman out in Washington telling people what to do. But they liked him less when he came back here and started telling our people what to do. Sam was the kiss of death in Prescott for a while. His popularity was at an all-time low. But he was back to being a hero with that crosswalk."[31]

Crosswalk caper

In 1986, the Prescott city council decided to eliminate a crosswalk as part of a road resurfacing project.[6] The crosswalk connected the local courthouse with an adjacent line of saloons known as Whiskey Row.[31] Public resentment over the removal soon developed and Steiger decided to take matters into his own hands.[32] According to local legend he used a paint brush to replace the crosswalk at night after visiting the nearby bars. In fact, he performed the action with a parking lot striping machine during the day.[6] As a result of the May 2, 1986, incident, Steiger was arrested and charged with criminal damage and disorderly conduct,[32] The disorderly conduct count was dropped but the criminal damage charge went to trial.[33] Steiger defended himself, arguing "it wasn't criminal damage, it was historic preservation."[6] He was acquitted by the jury after they had deliberated for 25 minutes.[33]

Governor's assistant

In 1987, Governor Evan Mecham appointed Steiger as a special assistant overseeing thirteen state agencies. One of these agencies was the Arizona Board of Pardons and Paroles. While working as special assistant, Steiger ordered pardons board member Ron Johnson to vote against requiring the resignation of fellow board member Patricia Castillo. As part of his instructions, Steiger informed Johnson that his appointment as a justice of the peace would be revoked if he did not comply. Johnson did not vote as instructed and Steiger had Johnson's judicial appointment revoked. Johnson responded by contacting Attorney General Bob Corbin who instructed Johnson to record a follow-up conversation between Johnson and Steiger confirming what had occurred.[6]

As a result, Steiger was charged with extortion.[34] Claiming he had been singled out for prosecution due to past differences with Attorney General Corbin, Steiger was found guilty of the charge on April 7, 1988, and sentenced to four years probation, a fine of US$5,500, and 700 hours of community service. Prior to the sentencing over 170 letters had been sent to the court in support of the defendant.[35] On September 21, 1989, the conviction was overturned by the Arizona Court of Appeals. In a 3–0 ruling, the court found the law Steiger was convicted under to be "unconstitutionally vague both because it provided insufficient guidance to those who make demands on others and because it permits arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement."[36]

Later life

In 1990, Steiger changed his party affiliation back from Libertarian to Republican and made a second run for governor.[37] The campaign was unsuccessful, with Steiger losing to Fife Symington III in the Republican primary.[38] The same year he released his book, Kill the Lawyers!, in which he discussed his various legal problems in a humorous manner.[39]

Steiger then became a local talk show host, his show being broadcast on both radio and television. In addition he published a political newsletter, The Burro Chronicles.[24] In 1999, Steiger ran for Mayor of Prescott, Arizona, on a slow-growth platform.[40] Following a single term in office, he left to return to the private sector.[41] Steiger suffered a stroke on September 20, 2002, that led him to be placed in an assisted living facility.[42][5] Steiger died in Prescott, Arizona, on September 26, 2012.[43]

See also

References

- 1 2 Boddie, John Bennett (1969). Historical Southern Families. Vol. 13. Clearfield. pp. 224–25. ISBN 0-8063-0524-X.

- 1 2 Johnson pp. 95

- 1 2 Rushlo, Michelle (April 28, 2000). "Sam Steiger still shooting from the hip, now as mayor of Prescott". Kingman Daily Miner. p. 11A. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ↑ Maisel, Louis Sandy; et al. (2001). Jews in American politics. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 425. ISBN 978-0-7425-0181-2.

- 1 2 Reinhart, Mary K. (June 2, 2014). "Former Arizona congressman Sam Steiger dies". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved June 29, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Duncan, Mark (December 12, 1999). "'Kill the Lawyers', unless you need one". The Daily Courier. pp. 1, 15.

- ↑ Bermane, David R. (1998). Arizona politics & government : the quest for autonomy, democracy, and development. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-8032-6146-2.

- ↑ "Glenn Makes Senate Look Petty: Steiger". Evening Prescott Courier. February 23, 1962. p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Barks, Cindy (December 12, 1999). "'The Tiger' grabs politics by the tail". The Daily Courier. pp. 1, 14–15.

- ↑ "All Dailies in Dist. 3 for Steiger". Evening Prescott Courier. October 23, 1964. p. 2.

- ↑ Timberlake, Roger (November 5, 1964). "Voting is Nearly Even for Barry". Evening Prescott Courier. p. 1.

- ↑ "Steiger Uncorks Verbal Poke". Evening Prescott Courier. May 26, 1966. p. 1.

- ↑ Hill, Gladwin (November 1, 1966). "Democrats Fear Arizona 'Pintos'". New York Times. p. 21.

- ↑ Chanberlain, John (November 16, 1966). "Labor Bosses Were Election Casualty". The Evening Independent. p. 12A.

- ↑ "House Hits Back at Critic Who Chided Colleagues". New York Times. February 6, 1968. p. 25.

- ↑ Johnson pp. 96

- 1 2 Lichtenstein, Grace (September 9, 1976). "Arizona Republicans Select Steiger, Slain Reporter's Friend, for Senate". New York Times. p. 33.

- ↑ "Steiger honored by national group". The Prescott Courier. December 16, 1971. p. 10.

- ↑ Hill, Gladwin (November 7, 1974). "Environmental Activists Hail Wide Victories of Their Candidates". New York Times. p. 31.

- ↑ "Our Campaigns – AZ District 3 Race – Nov 05, 1974". Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Steiger claims self defense in killing of burros". The Prescott Courier. August 11, 1975. p. 1.

- ↑ Thompkins, Tomy (August 17, 1975). "Burro shooting part of lengthy hassle". The Prescott Courier. p. 1.

- ↑ "$76,200 suit filed against Sam Steiger". The Prescott Courier. August 31, 1975. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- 1 2 Kim, Eun-Kyung (November 27, 1995). "Burro chronicles kicks politicos". The Daily Courier. p. 1B. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- 1 2 "Arizona Shootout". Time. September 20, 1976. Archived from the original on June 8, 2008.

- ↑ Lichtenstein, Grace (October 28, 1976). "Arizona Polls Show a Democrat Leading Steiger in Senate Race". New York Times. p. 48.

- ↑ "Deconcini Bumps Steiger". Kingman Daily Miner. November 3, 1976. pp. 1, 6A.

- ↑ Waters, Charlie (May 23, 1978). "Steiger challenges Tenney for Senate seat". The Prescott Courier. p. 1.

- ↑ Millman, Joel (October 20, 1982). "Candidates disagree on secretary of state's role". The Courier. p. 3.

- ↑ "Official Canvas - 1982 General Election" (PDF). Phoenix, Arizona: Arizona Secretary of State. November 1982. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-02.

- 1 2 Johnson pp. 97

- 1 2 Holquist, Robert C. (June 4, 1986). "Citizens Cross Council On Walkway". The Courier. p. 1.

- 1 2 Holquist, Robert C. (June 20, 1986). "Jury acquits crosswalk painter". The Courier. pp. 1, 5.

- ↑ "Aid to governor charged". Eugene Register-Guard. October 17, 1987. p. 3A.

- ↑ "Bully Steiger Sentenced To 4 Years Probation". The Prescott Courier. June 3, 1988. p. 3A.

- ↑ "Court reverses Steiger conviction". Mohave Daily Miner. September 22, 1989. p. 5.

- ↑ Hostetler, Darrin (July 25, 1990). "Steiger to Libertarians: I Switched". Phoenix New Times. Archived from the original on 2010-07-19. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ↑ Alexieff, Michael (September 12, 1990). "Symington to face Goddard for governor". The Prescott Courier. pp. 1, 5.

- ↑ Johnson pp. 99

- ↑ Barks, Cindy (August 24, 1999). "Steiger speaks his mind on property rights, other issue". The Daily Courier.

- ↑ Barks, Cindy (December 28, 2001). "Prescott's first mail-in election seats Mayor Simmons, three on City Council". The Daily Courier. pp. 1, 12. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ↑ Herbert, C Murphy (September 25, 2002). "Steiger's spirits are high; he's 'doing better' after stroke". The Daily Courier. pp. 1, 13. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ↑ "5-term Arizona congressman Sam Steiger dies at age 83". The Republic. Columbus, Ohio. Associated Press. September 28, 2012.

- Johnson, James W. (2002). Arizona Politicians: The Noble and the Notorious. illustrations by David `Fitz' Fitzsimmons. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-2203-0.

External links

- United States Congress. "Sam Steiger (id: S000846)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- "Interview with Sam Steiger" (PDF). (48 KB) from The Morris K. Udall Oral History Project, University of Arizona Library, Special Collections