Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) is a suite of instruments on the Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity rover. The SAM instrument suite will analyze organics and gases from both atmospheric and solid samples.[1][2] It was developed by the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, the Laboratoire des Atmosphères Milieux Observations Spatiales (LATMOS) associated to the Laboratoire Inter-Universitaire des Systèmes Atmosphériques (LISA) (jointly operated by France's Centre national de la recherche scientifique and Parisian universities), and Honeybee Robotics, along with many additional external partners.[1][3][4]

Instruments

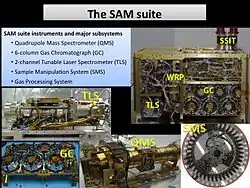

The SAM suite consists of three instruments:

- The quadrupole mass spectrometer (QMS) detects gases sampled from the atmosphere or those released from solid samples by heating.[1][5]

- The gas chromatograph (GC) is used to separate out individual gases from a complex mixture into molecular components. The resulting gas flow is analyzed in the mass spectrometer with a mass range of 2–535 daltons.[1][5]

- The tunable laser spectrometer (TLS) performs precision measurements of oxygen and carbon isotope ratios in carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) in the atmosphere of Mars in order to distinguish between their geochemical or biological origin.[1][4][5][6][7]

Subsystems

The SAM has three subsystems: the 'chemical separation and processing laboratory', for enrichment and derivatization of the organic molecules of the sample; the sample manipulation system (SMS) for transporting powder delivered from the MSL drill to a SAM inlet and into one of 74 sample cups.[1] The SMS then moves the sample to the SAM oven to release gases by heating to up to 1000 °C;[1][8] and the pump subsystem to purge the separators and analysers.

The Space Physics Research Laboratory at the University of Michigan built the main power supply, command and data handling unit, valve and heater controller, filament/bias controller, and high voltage module. The uncooled infrared detectors were developed and provided by the Polish company VIGO System.[9]

Timeline

- 9 November 2012: A pinch of fine sand and dust became the first solid Martian sample deposited into the SAM. The sample came from the patch of windblown material called Rocknest, which had provided a sample previously for mineralogical analysis by CheMin instrument.[10]

- 3 December 2012: NASA reported SAM had detected water molecules, chlorine and sulphur. Hints of organic compounds couldn't be ruled out as contamination from Curiosity itself, however.[11][12]

- 16 December 2014: NASA reported the Curiosity rover detected a "tenfold spike", likely localized, in the amount of methane in the Martian atmosphere. Sample measurements taken "a dozen times over 20 months" showed increases in late 2013 and early 2014, averaging "7 parts of methane per billion in the atmosphere." Before and after that, readings averaged around one-tenth that level.[13][14] In addition, high levels of organic chemicals, particularly chlorobenzene, were detected in powder drilled from one of the rocks, named "Cumberland", analyzed by the Curiosity rover.[13][14]

- 24 March 2015: NASA reported the first detection of nitrogen released after heating surface sediments on the planet Mars. The nitrogen in nitrate is in a "fixed" state, meaning that it is in an oxidized form that can be used by living organisms. The discovery supports the notion that ancient Mars may have been habitable for life.[15][16][17]

- 4 April 2015: NASA reported studies, based on measurements by the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument on the Curiosity rover, of the Martian atmosphere using xenon and argon isotopes. Results provided support for a "vigorous" loss of atmosphere early in the history of Mars and were consistent with an atmospheric signature found in bits of atmosphere captured in some Martian meteorites found on Earth.[18]

- 15 November 2020, NASA scientists including Joanna Clark, were able to replicate a Mars simulant based soil using SAM, on Earth called JSC-Rocknest which is being used for a series of tests including heating it to different temperatures to determine its water re-absorption rate and ability to be broken down into compounds needed for liveable conditions.[19]

- 1 November 2021: Astronomers reported detecting, in a "first-of-its-kind" process based on SAM instruments, organic molecules, including benzoic acid, ammonia and other related unknown compounds, on the planet Mars by the Curiosity rover.[20][21]

by the Curiosity rover (August 2012 to September 2014).

Gallery

Videos

See also

- Thermal and Evolved Gas Analyzer (Phoenix lander)

- Urey instrument

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "MSL Science Corner: Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM)". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ↑ Overview of the SAM instrument suite

- ↑ Cabane, M.; et al. (2004). "Did life exist on Mars? Search for organic and inorganic signatures, one of the goals for "SAM" (sample analysis at Mars)" (PDF). Advances in Space Research. 33 (12): 2240–2245. Bibcode:2004AdSpR..33.2240C. doi:10.1016/S0273-1177(03)00523-4.

- 1 2 "Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) Instrument Suite". NASA. October 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- 1 2 3 Mahaffy, Paul R.; et al. (2012). "The Sample Analysis at Mars Investigation and Instrument Suite". Space Science Reviews. 170 (1–4): 401–478. Bibcode:2012SSRv..170..401M. doi:10.1007/s11214-012-9879-z.

- ↑ Tenenbaum, D. (9 June 2008). "Making Sense of Mars Methane". Astrobiology Magazine. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ↑ Tarsitano, C. G.; Webster, C. R. (2007). "Multilaser Herriott cell for planetary tunable laser spectrometers". Applied Optics. 46 (28): 6923–6935. Bibcode:2007ApOpt..46.6923T. doi:10.1364/AO.46.006923. PMID 17906720.

- ↑ Kennedy, T.; Mumm, E.; Myrick, T.; Frader-Thompson, S. (2006). "Optimization of a mars sample manipulation system through concentrated functionality" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-27. Retrieved 2012-08-03.

- ↑ "Vigo System / Vigo IR Detectors on Mars". Vigo.com.pl. 13 December 2011. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ "Rover's 'SAM' Lab Instrument Suite Tastes Soil". JPL-NASA. 13 November 2012.

- ↑ Brown, Dwayne; Webster, Guy; Neal-Jones, Nancy (3 December 2012). "NASA Mars Rover Fully Analyzes First Martian Soil Samples". NASA. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ↑ "'Complex chemistry' found on Mars". 3 News NZ. 4 December 2012. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- 1 2 Webster, Guy; Neal-Jones, Nancy; Brown, Dwayne (16 December 2014). "NASA Rover Finds Active and Ancient Organic Chemistry on Mars". NASA. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- 1 2 Chang, Kenneth (16 December 2014). "'A Great Moment': Rover Finds Clue That Mars May Harbor Life". New York Times. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ↑ Neal-Jones, Nancy; Steigerwald, William; Webster, Guy; Brown, Dwayne (24 March 2015). "Curiosity Rover Finds Biologically Useful Nitrogen on Mars". NASA. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ↑ "Curiosity Mars rover detects 'useful nitrogen'". NASA. BBC News. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 2015-03-25.

- ↑ Stern, Jennifer C. (24 March 2015). "Evidence for indigenous nitrogen in sedimentary and aeolian deposits from the Curiosity rover investigations at Gale crater, Mars". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (14): 4245–50. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.4245S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1420932112. PMC 4394254. PMID 25831544.

- ↑ Brown, Dwayne; Neal-Jones, Nancy (31 March 2015). "RELEASE 15-055 Curiosity Sniffs Out History of Martian Atmosphere". NASA. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ "JSC-Rocknest: A large-scale Mojave Mars Simulant (MMS) based soil simulant for in-situ resource utilization water-extraction studies". Icarus. 351. November 15, 2020.

- ↑ Rabie, Passant (1 November 2021). "Organic Molecules Found On Mars For The First Time - The Curiosity rover demonstrated a useful technique to search for Martian biosignatures". Inverse. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ↑ Millan, M.; et al. (1 November 2021). "Organic molecules revealed in Mars's Bagnold Dunes by Curiosity's derivatization experiment". Nature Astronomy. 6: 129–140. doi:10.1038/s41550-021-01507-9. S2CID 256705528. Retrieved 2 November 2021.