Samuel Chidley | |

|---|---|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1616 Shrewsbury |

| Died | 1672 or later. Shrewsbury |

| Political party | Leveller |

| Spouse | Mary |

| Relations |

|

| Profession | Haberdasher |

| Signature | |

Samuel Chidley (1616–c. 1672) was an English Puritan activist and controversialist. A radical separatist in London before and during the English Civil War, he became a leading Leveller, a treasurer of the movement. A public servant and land speculator under the Commonwealth and Protectorate, he became rich and campaigned for social, moral and financial reform. He was ruined by the Restoration and returned to live in relative poverty in his native Shrewsbury.

Origins and early life

| Part of a series on |

| Puritans |

|---|

|

Samuel Chidley was the first surviving son of

- Daniel Chidley, listed in 1621 by the Shrewsbury Burgess Roll, under the spelling Chidloe, as a tailor and the son of William, a yeoman of Burlton, a village to the north of Shrewsbury.[1]

- Katherine Chidley, Daniel's wife, whose origins are unknown.[2]

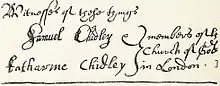

The Burgess Roll records Samuel himself as being four years of age. Assuming this is correct, he was about two years old when his christening was recorded in the parish register of St Chad's Church, Shrewsbury on 13 April 1618:[3] Here his father is called "Daniell Chedler:" although earlier documents record the surname with numerous spellings, Katherine and Samuel consistently used the form Chidley in their signatures and title pages. It has been suggested that the naming of Samuel was a deliberate allusion to the Biblical story of Hannah, who in 1 Samuel 1:21–28 dedicated her first child, Samuel, to God and refused the traditional purification ritual until the child was weaned.[4] This suggests that Samuel was intended from the outset as the child who would be dedicated to God's work.

Daniel and Katherine Chidley were denounced as separatists by the Puritan public preacher of Shrewsbury, Julines Herring,[5] and this separatism may account for their reluctance to have their children baptised at their parish church. However, by 1629 St Chad's had baptised a further seven Chidley children and buried one, Daniel, who died in infancy.[6] The second Daniel's baptism was recorded on 12 February 1626,[7] and after this birth, at least, Katherine refused to undergo the Churching of women, although this may not have been the first time, and she was not unique. She and six other women were cited for refusing to take part later in the year during an episcopal visitation.[8] This was part of protracted hostilities between the High Church incumbent, Peter Studley, and his Puritan parishioners in which both the separatists and the moderate Presbyterians around Herring were accused of absenting themselves from the Eucharist and setting up conventicles.

Separation and advancement in London

The decision of the Chidley's to move to London has been attributed to both religious persecution.[9] and a desire for relative anonymity.[2] In 1630 Daniel Chidley, described as the Elder, together with John Dupper or Duppa and Thomas Dye, helped to form a separatist church in London.[10][11] Frequently referred to by historians as the Duppa church, this splinter group rejected the baptism of Anglican parish churches and on these grounds broke away from an Independent church led by John Lothropp.[12] The initiative seems originally to have stemmed from Duppa's demand that Lothropp's church, in renewing its covenant, should "Detest & Protest against ye Parish Churches." The splinter group were lucky to avoid the wave of arrests that struck the more visible parent body in 1632.[13] Samuel Chidley lived with his parents as an adult in London, and with his mother until at least 1652.[9] He seems to have been active with his parents in their separatist group, supporting John Lilburne from the 1630s, during the period of Thorough, the attempt by Charles I to practise absolute monarchy. David Brown, a veteran of the group led by Duppa and the Chidleys reminisced about tearing a surplice as a deliberate act of iconoclasm one St Luke's Day (18 October) at Greenwich, a place made notorious in their eyes for the Catholic chapel that Queen Henrietta Maria had installed in her house there.[14]

The Chidleys seem also to have been very open to the economic opportunities afforded by the capital. Daniel became a freeman of the Worshipful Company of Haberdashers in 1632.[15] Samuel, was admitted to the company as an apprentice in 1634.[16]

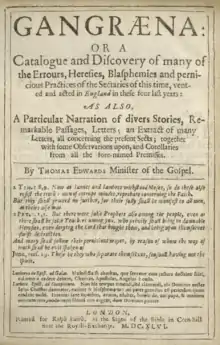

The Chidleys' anonymity was decisively ended with the collapse of Thorough and the king's reluctant decision to call Parliaments. The Scottish Covenanters had defeated the king in the Bishops' Wars and when Parliament entered into negotiations for an alliance, pressed for a Presbyterian reformation of the Church of England.[17] At this juncture, Thomas Edwards, an irascible English Presbyterian controversialist, published Reasons Against the Independent Government of Particular Congregations, an attack on the Congregational polity. In October 1641, Katherine Chidley issued a counterblast: The Justification of the Independant Churches of Christ. Being an Answer to Mr. Edwards his Booke.[2] The Biblical texts she placed on the title page both attested her preference for thinking through the experience of the Judges and the early Israelite monarchy, tending to confirm the significance of Samuel's name. 1 Samuel 17:45, allowed her to take on the role of David, while Judges 4:21allowed her to be Jael.[18]

Samuel had begun his pamphleting career by 1643/4, when he released A Christian plea for Christians baptisme, a defence of infant baptism against the Particular Baptist Andrew Ritor's A Treatise of the Vanity of Childish Baptism, which had also strongly upheld baptism by immersion.[19]

The high places

Samuel Chidley acted as spokesman for his church repeatedly in the 1640s, invariably on a variation of Duppa's founding principle of "Detest & Protest against ye Parish Churches." The first recorded instance seems to have been in June 1645, when he, together with two other members, John Duppa and David Brown, took part in a conference with Henry Burton of St Matthew Friday Street.[20] At the time, they were calling their group the Separation. The key tenet they wished to defend in the debate was that the former parish churches were to be shunned and demolished as were the "high places" of the Ancient Canaanite religion by the kings of Judah. Brown helpfully included a list of what the Separation regarded as relevant texts in his report of the conference,[21] including 2 Chronicles 14:2–5, an account of Asa's destruction of the Canaanite shrines. The separatist position was in direct contradiction to the concluding statement of the Directory for Public Worship, adopted by an act of parliament in January 1645 to replace the Book of Common Prayer.

- As no place is capable of any holiness under pretence of whatsoever Dedication or Consecration, so neither is it subject to such pollution by any superstition formerly used and now laid aside, as may render it unlawfull or inconvenient for Christians to meet together therein for the publique worship of God. And therefore we hold it requisite that the places of publique assembling for worship among us should be continued and imployed to that use.[22]

Thomas Edwards, in the first part of Gangraena, related an incident two months later in which Katherine Chidley debated at Stepney Meeting House with the moderate Independent William Greenhill, noting the Chidleys' distinctive avoidance of places previously dedicated to Saints and Angels, which they regarded as sites of idolatry.[23]

Samuel Chidley emerged as his mother's key assistant in her evangelism, helping her to plant new separatist churches. One of these was at Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk and its covenant of 1646 has survived. It was affirmed in the names of eight adults and six children, with both Katherine and Samuel Chidley signing as witnesses. The covenant was radically separatist and strongly reflects the Chidleys' preoccupation with boycotting the old parish churches. Its members were "conuinced in conscience of the evill of ye Church of England, and of all other states wch are contrary to Christs institution."[24] They declared themselves "fully separated" not only from Anglicans but also those who had dealings with them, as well as the "high places" they had used for worship. Beside their signatures, Samuel and Katherine Chidley described themselves as "members of the Church of God in London."

Edwards specifically mentioned the Suffolk mission in the third part of Gangraena:

- There is one Katherine Chidly an old Brownist, and her sonne a young Brownist, a pragmaticall fellow, who not content with spreading their poyson in and about London, goe down into the Country to gather people to them, and among other places have been this Summer at Bury in Suffolke, to set up and gather a Church there, where (as I have it from good hands) they have gathered about seven persons, and kept their Conventicles together[25]

Edwards alleged that the Chidleys worked together "one inditing, the other writing," and that they had issued a polemical pamphlet against him from Bury. He was certain that their work in Suffolk was part of a wider pattern of planting such congregations.

The theme of the high places dominated all of Samuel Chidley's contributions to his own church's mission in this period. Although explicitly directed against the Anglican and former Catholic places of worship, it was used exclusively in debates with other Independent churches which the members of the Separation or Church of God in London regarded as insufficiently rigorous and from which they wished to distinguish themselves. This became increasingly important as the attempt to impose a Presbyterian polity, which had so concerned all Independents, foundered in the face of opposition from within army.[26] The Presbyterian structures that had been built fell into neglect after 1648,[27] mainly because the Second English Civil War, stemming from the king's conspiracy to have himself restored by a Scottish invasion, finally discredited the Presbyterian system and its Parliamentarian supporters and brought effective toleration for the Independents.[26]

In August 1648 Samuel Chidley debated with John Goodwin, the minister of St. Stephen Coleman Street, who had attempted a compromise between a gathered church and a parish church: he used St Stephen's as a teaching and preaching base in this most turbulent and lively part of the capital, while administering communion only to the select group, not necessarily from the area, approved by himself and his elders.[28] Differences between Chidley and Goodwin initially centred on the domestic problems of the Goodsones: the husband, William Goodsone, an officer in the navy, attended Chidley's Separation, while his wife worshipped at St Stephen's, as Chidley outlined in a letter to Goodwin.[29] It seems likely the two churches were close and to some extent competitors for local support. According to Brown's report, which was bundled with his notes on the earlier conference with Burton, the discussion began with Goodwin making the eirenic gambit:

- Suppose it be granted that all our matter be so corrupt, as you presuppose it is, yet it is lawfull for your Members to communicate with ours; for saith he, it is lawfull for a man to communicate with one whom he doubts whether he be a Believer or not.[30]

This was contested by Chidley who took the rigorist position:

- First, That whatsoever is doubtfull is not to be practised, though it be a thing indifferent, because it is not of faith, and therefore a sin, because whatsoever is not of faith is sin. Secondly, much more is he to forbeare that which is contrary to the word of God, as to communicate with one of whom we have not good testimony of his life and conversation, and that the work of grace is wrought upon him, that he is effectually called, and separated from Idolatry, and cleaveth unto the Way of Christ in purity.

William Goodsone himself said that he could not be in communion with Goodwin's church "because Mr. Goodwins Peoples practice was to preach and heare in the Parrish-Churches of England, and to Worship in the Idolls Temples, and to Baptize the Children of unbelievers, and such like." Almost immediately the debate moved on to the question of the high places,[31] the separatists' distinctive theme, and did not stray from it until the end.

Leveller

.jpg.webp)

By the time of his debate with John Goodwin, Samuel Chidley had earned a reputation as a prominent Leveller. He and Thomas Prince became the treasurers of the movement, which was based on Independents within the army. With the key leaders, John Lilburne and Richard Overton in prison, Chidley and Prince were especially important in the latter part of 1647, as capable and literate proponents of the cause.[32] During this period, the first Agreement of the People took shape among the Agitators, the representatives of the soldiers, setting out a series of demands that they considered would protect the gains made in the Civil War and constituting a rejection of the army commanders' Heads of Proposals. The Agreement provided part of the agenda for the Putney Debates in October, between the army and its commanders. With the inconclusive ending of the debates, Samuel Chidley was one of those who took forward the Agreement[9] as a propaganda document to a rendezvous of the army at Corkbush Field, near Ware, Hertfordshire, where the commanders hoped for a decision in favour of the Heads of Proposals and of Thomas Fairfax personally. It was rumoured that the army radicals were to be joined by a large force, up to 20,000, of London weavers,[33] a constituency to which Chidley had ready access. The resulting Corkbush Field mutiny of 15 November 1647 was suppressed mainly by the prompt action of Oliver Cromwell, who ordered the immediate execution by shooting of a single Leveller, Richard Arnold of Robert Lilburne's regiment.[34]

Chidley seems to have been greatly exercised by the issue of capital punishment even at this stage, and an "inquisition for the blood"[35] of Private Arnold was one of the requests he and small delegation now took in a petition to Parliament, presented on 23 November 1647, and entitled "The humble Petition of many free-born People of England."[36] The petition was included in a letter to the Speaker, William Lenthall, and sent to a committee, which quickly rejected it, on the ground that it was

- a seditious and contemptuous Avowing and Prosecution of a former Petition, and Paper annexed, stiled, "An Agreement of the People," formerly adjudged by this House to be destructive to the Being of Parliaments, and fundamental Government of the Kingdom.

The Petition of the People had been submitted to the House two weeks earlier, on 9 November, when the expression "destructive to the Being of Parliaments, and to the fundamental Government of the Kingdom" was first used.[37] The document made numerous demands about the conduct of Parliament and of elections, including that a dissolution of the Parliament be scheduled for 30 September 1648[38] and that Parliaments thereafter be of a fixed two-year term, with elections on the first Thursday in March.[39] The petition also challenged Parliamentary sovereignty by asserting that "the power of this, and all future Representatives of this Nation, is inferior only to theirs who choose them,"[40] and proposing to exclude from political control "matters of religion and the ways of God's worship." Having rejected these demands already as seditious, the House was now able to hold the Leveller petitioners as guilty of sedition and contempt of court. Chidley and Prince, described as a Cheesemonger, were imprisoned in the gatehouse of Parliament during the pleasure of the house.[41] The three Levellers accompanying the, Jeremy Ives, Thomas Taylor, and William Larner were committed to Newgate Prison. To rub salt in the wound, the House also deputed Sir John Evelyn to write a letter thanking Cromwell for the summary execution of Arnold and urging him to carry out further "condign and exemplary Punishment."

Chidley and Prince had escaped fairly lightly, in view of the possibility of a prosecution for sedition. It seems that Chidley's incarceration was short, as he was involved in organising a Leveller petition again in January 1648.[9] The documents at the forefront of Leveller agitation at that time were John Lilburne's Earnest Petition,[42] which called for a greatly extended suffrage, election of magistrates and other constitutional innovations,[43] and The mournful cries of many thousand poor tradesmen, which drew attention to widespread economic distress.[44] It seems likely that Chidley played his part in arguing for these. He was almost certainly involved also in the 1649 petitioning of Parliament after the arrest of four Leveller leaders, Lilburne, Overton, William Walwyn and Prince: it is thought that his mother wrote the women's petition on this occasion.[45] However, the movement was effectively defeated or sidelined during the course of that year and Chidley's only other major involvement was when Lilburne was imprisoned for a final time in 1653.[46] When Katherine Chidley organised a women's petition, Edward Hyde, the royalist commentator, was told that it gathered over 6000 female signatures[47] and that "the ringleader was the wife of one Chidley, a prime Leveller." It is likely that Hyde mistook the relationship and meant Samuel Chidley: his father, Daniel, was by this time dead and had never been a "prime Leveller."

Businessman

Although committed to an austere and rigorous Puritan sect and a radical political movement, Samuel Chidley found opportunities to prosper as a businessman and administrator. He became a Freeman of the Haberdasher's Company in 1649.[48] His father became a Master of the Company in the same year[49] but does not seem to have long survived.[2] Katherine Chidley continued her husband's business, probably with Samuel's help, and it was she who was named as payee for over £350 worth of stockings for the army involved the final phases of the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland.[50][51]

In 1649, the year he became a freeman of the Haberdashers' Company, Samuel Chidley was appointed Register of Debentures,[9] a post he acquired allegedly with the assistance of David Brown.[14] This was part of Parliament's scheme to use the value of Crown Estates in England and Wales to meet the huge pay arrears of the New Model Army. The troops received, in lieu of pay, debentures that allowed them to purchase portions of the royal estates left owner-less by the execution of Charles I.[52] The scheme was ultimately to realise £1,434,239. The necessary legislation for the sale of the royal family's property was passed on 11 July 1649,[53] acknowledging in its preface that Parliament was "engaged both in Honor and Justice to make due satisfaction unto all Officers and Soldiers for their Arrears,"[54] although Chidley's post had already been established on 22 June. He was based in Worcester House,[9] then a prestigious address near St James Garlickhythe, used by the Worshipful Company of Fruiterers and with a notable view across the River Thames.

Chidley used his post as an access point for private business, buying debentures speculatively on his own account and buying fifteen lots of crown land, not all for his own possession: the manor of Greens Norton in Northamptonshire was sold back to thirteen of the tenants. He did, however, build up a substantial property portfolio in London, mainly in the St Giles in the Fields and High Holborn areas. Accusations of fraud and lawsuits followed. It seems that David Brown, now disillusioned with Chidley's leadership of the Separation as well his personal probity, was behind some of the disquiet.[14] In the resultant internal power struggle, Brown, who claimed to be one of the longest-serving members, was excommunicated from the sect. In 1652 Brown and Chidley clashed in print, with Chidley publishing a riposte to an attack by Brown on the Leveller leadership: The Dissembling Scot Set Forth in his Coulours. Chidley continued to prosper throughout the Protectorate.

Campaigner and pamphleteer

Chidley had written pamphlets earlier in his career. In the 1650s, however, he released a series of short leaflets, pamphlets and books, creating controversy and discussion.

Capital punishment

Chidley's campaign against the death penalty for theft was launched well before his 1652 book Retsah, a cry against a crying sinne, as it is made up documents he had already submitted in furtherance of his aims. Retsah was the transliteration, accepted at the time, of the Hebrew word for killing or murder in the Ten Commandments. Chidley's preface stated his position immediately:

- THis little Book reflecteth upon all those who have broken the Statute Lawes of God, by killing of men merly for Theft, Let such sinners who are the Judges, or Executioners of such over-much Justice, be ashamed, and confounded for defiling the Land with Bloud;[55]

There followed documents he had presented to the City of London Corporation, to Thomas Andrewes, who had been Lord Mayor of London for the year 1650–1, to the English Council of State and to Parliament's own committee on law reform. In his submission to London's councillors, Chidley made clear his contention that the lex talionis was a strict limit, not a minimum demand:

- According to the rule of Equity, there is required life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burning for burning, wound for wound, stripe for stripe, Exod. 21:23–25. It is not life for eye, but eye for eye; not eye for tooth, but tooth for tooth; so that if a man require more it is iniquity, Prov. 30:6.[56]

However, the most substantial document was that presented to the Army Council by Colonel Thomas Pride, the instigator in 1648 of the famous Pride's Purge that cleared the Commons of its Presbyterian majority. Pride was a member of the Separation[57] and seems to have been willing at this stage to associate himself with Chidley. The basic argument was set out as a near-syllogism.

- That God is the only lawmaker;…

- God hath no where given liberty, but hath prohibited, that the life of any Man should be taken away for stealing…

- The putting them to death is expresly against the Law of God…[58]

He added that the death penalty for theft permanently prevented the victim ever receiving due compensation. At several points in the argument, Chidley appeals not just to Biblical authority but to reason against what he calls "the irrationall and irregular proceedings of men."[59] It had now been established by the courts, claimed Chidley, that only 13 pence need be stolen for the convicted thief to be hanged.

- THis murdering Law is the cause wherefore many murders are committed by Robbers in the act of stealing, for the Theeves know its a hanging matter to steale, and its no more to commit murder.[60]

Even more perversely, it discouraged prosecution, as the injured party knew the litigation might be costly and troublesome, without hope of recovering any losses.[61] Noting that the Biblical solution to the problem was enslavement for theft, Chidley suggested a period of forced labour to compensate the victim, as already practised in the Dutch Republic, mentioning plantation slavery or employment in the mines. However, this was presumably intended only for very serious cases, as he argued "They are not sold for ever, but only for their Theft, and its a worser slavery, and a great tyranny indeed, to take away their lives."[62] He suggested a thief should generally be expected to make double restitution, but four-fold if the money had already been spent. Chidley did not take up fully the more difficult issue of capital punishment for murder, but was confident that "If this course were well followed, Tyburne would lose many Customers, for it would much abate the number of Theeves, and Murderers."[63]

Public debt

Chidley's campaign on public debt quickly led to a breach with Colonel Pride, the most prominent member of the Separation. Pride had both a professional and a personal interest in the issue of arrears in the army. He received debentures but also bought them from the men of his regiment, presumably using Chidley's good offices, and used them to acquire Nonsuch Great Park or Worcester Park in Surrey for £11,591.[57] However, Chidley launched a campaign in December 1652 for a more prompt settlement between the Rump Parliament and state creditors, who were offered repayment only if they "doubled", i.e. immediately advanced the identical sum again. He issued a leaflet announcing a mass petition to be organised at the Bell Savage Inn on Ludgate Hill. This and explicitly recommended the petition to those "are desirous to bee satisfied out of that Security which is propounded to the Parliament by Collonel PRIDE, D. GEURDAIN, and the rest of the UNDER-TAKERS on behalfe of the COMMON-WEALTH,"[64] suggesting, perhaps intentionally, that Chidley's agitation was aligned with Pride's initiative. Moreover, the use of upper case type turned this into a major selling point. Pride, however, publicly dissociated himself from Chidley's venture,[57] and the breach between the two men seems to have been permanent.

Chidley continued his attempt to build a popular movement of creditors. In December 1653, after the dissolution of the Rump, he issued another pamphlet, A Remonstrance to the Creditors of the Common-Wealth of England, giving a critique of Parliament's arrangements for settling public debt, particularly its concentration of efforts on those who had served in Ireland rather the much older debts accrued in the English Civil War.[65]

Thunder from the Throne of God

In 1656 Chidley returned to an old theme, presenting to the Second Protectorate Parliament Thunder from the Throne of God Against the Temples of Idols, a denunciation of the "high places", packed with supporting Biblical texts and fiery rhetoric.[66] Chidley inveighed in particular against bell towers and steeples as relics of the Catholic past, demanding their complete destruction: "Down with them and their Babylonish Bells, to the very ground, and let not a stone of them remain upon another."[67] The title was apparently inspired by a recent lightning strike at St Botolph's Church, Boston, a very prominent Lincolnshire landmark. The book is generally reckoned to have been written some years earlier, perhaps in early 1653. However, it certainly came before Parliament only in 1656. It seems that Chidley had the book delivered to the House of Commons, accompanied by a letter to Cromwell. It was drawn to the members' attention on 20 October 1656 by Colonel Jephson.[68] Chidley was summoned to the bar of the House and the book and letter shown to him: "Who acknowledged he wrote the Epistle; and doth own it, and all that is in it; and owns the Book too, and all in it, the Printer's Errors excepted." The book was then referred to a committee, which included Jephson and Colonel Shapcott, an MP who had complained to the previous parliament when he became the subject of a scurrilous publication.[69] Later in the session, the House decided to use the same committee for a more general review of censorship. It committed Chidley to the custody of the Serjeant at Arms.[70] As on the previous occasion, he was not detained long: the House released him after hearing his humble petition on 28 October.[71]

To His Highness

The following year Chidley issued a general diatribe addressed To his Highness the Lord Protector, and the Parliament of England, &c. Beginning with a ringing announcement of the brotherhood of all humans in the image of God,[72] he went on to bemoan the inactivity of Parliament:

- You have sate now above these 40 days twice told, and passed some Acts for transporting Corn and Cattel out of the Land, and against Charls Stuart's, &c. but (as I humbly conceive) have left undone matters of greater concernment...[73]

These lapses, he predictably announced, included a failure to abolish the death penalty for theft and leaving the public debt unpaid.[74] This allowed him to unite both issues in a picture of a land where there was no support for the poor, who were excluded from the enclosed fields and orchards, justice was denied, lawyers prospered by lying, while beggars and thieves swarmed.[75] He concluded by pointing out the responsibility for the state of the nation lay with Parliament, urging it to "unbinde, loosing the bnds of wickedness, undoing the heavy burdens, and letting the oppressed go free, and breaking every yoke."

Increasing difficulties

And because, in the continued Distractions of so many Years, and so many and great Revolutions, many Grants and Purchases of Estates have been made, to and by many Officers, Soldiers, and others, who are now possessed of the same, and who may be liable to Actions at Law upon several Titles: We are likewise willing, that all such Differences, and all Things relating to such Grants, Sales, and Purchases, shall be determined in Parliament, which can best provide for the just Satisfaction of all Men who are concerned.

The Declaration of Breda, according to the House of Lords Journal.[76]

Chidley seems to have become increasingly dogged by ill-fortune and political change as well as his own mistakes in the later years of the Protectorate: a pattern that continued after 1660. On 9 May 1657 he again clashed with the House of Commons. Although the circumstances are unclear, the House noted that Chidley was involved in legal action against Robert Fenwick, an MP for Northumberland, and Ralph Darnall, a Commons official and brother of the prominent lawyer Philip Darnall. By bringing against them Subpoenas from the Court of Chancery while the House was in session, Chidley had breached parliamentary privilege. Once again the House committed him to custody as a delinquent.[77] In 1659 Chidley and his wife, Mary, were summoned to the Court of King's Bench, charged with a serious assault on a servant girl.[9]

The return of the monarchy in 1660 brought far greater difficulties. Crown lands were taken back into royal ownership, despite an apparent promise to the contrary in the Declaration of Breda. This effectively ruined Chidley and many like him, whose fortunes were founded on land speculation under the Commonwealth. The publication information he attached to Retsah[78] and the Remonstrance on public debt[65] both showed Chidley living on Bow Lane, near St Mary-le-Bow. A decade later, in 1662, he was in a house of two hearths in Chequer Alley in the Bishopsgate Ward,[79] part of the densely populated area[80] to the east of Coleman Street.

Chidley seems to have suffered all the vicissitudes of Restoration London. In 1664 he was imprisoned as a Nonconformist, for refusing to take the oaths of allegiance and supremacy.[9] Although the details are unknown, he is said to have lost his family in 1665's Great Plague of London and much of his remaining property in 1666's Great Fire of London. In 1668 he was imprisoned again as a disturber of the peace.

Last years and death

Chidley is known to have spent his last years in his native Shrewsbury, where he occupied a house with a single hearth in 1672. He died some time thereafter.

Footnotes

- ↑ Shrewsbury Burgess Roll, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 4 Gentles, Ian J. "Chidley, Katherine". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37278. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Register of St Chad's, Shrewsbury, p. 7.

- ↑ Gillespie, p. 80.

- ↑ Clarke. p. 465.

- ↑ Coulton, p. 82-3.

- ↑ Register of St Chad's, Shrewsbury, p. 46.

- ↑ Coulton, p. 83.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Gentles, Ian J. "Chidley, Samuel". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37279. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Burrage, volume 1, p. 321.

- ↑ Burrage, volume 2, p. 299.

- ↑ Burrage, volume 2, p. 301-2.

- ↑ Burrage, volume 1, p. 322-3.

- 1 2 3 Brown (1652), p. 14.

- ↑ Haberdashers' register of Apprentices and Freemen 1526-1933.

- ↑ Haberdashers' register of Apprentices and Freemen 1526-1933.

- ↑ Shaw, volume 1, p. 128-9.

- ↑ The Justification of the Independant Churches, Title page.

- ↑ Ritor (1642).

- ↑ Brown (1650), p. 1.

- ↑ Brown (1650), p. 8.

- ↑ Acts and Ordinances of the Interregnum, 1642-1660: An Ordinance for taking away the Book of Common Prayer, and for establishing and putting in execution of the Directory for the publique worship of God.

- ↑ Edwards (1646), p. 79-80.

- ↑ Bury St Edmund's Church Covenants, p. 334.

- ↑ Edwards (1646), p. 170

- 1 2 Shaw, volume 2, p. 34ff.

- ↑ Shaw, volume 2, p. 28.

- ↑ Johns, p. 41.

- ↑ Brown (1650), p. 9.

- ↑ Brown (1650), p. 10.

- ↑ Brown (1650), p. 11.

- ↑ Brailsford, p. 256.

- ↑ Brailsford, p. 289.

- ↑ Brailsford, p. 296-7.

- ↑ Brailsford, p. 311.

- ↑ House of Commons Journal Volume 5: 23 November 1647: Petition from free-born People of England.

- ↑ House of Commons Journal Volume 5: 9 November 1647: Petition of the People.

- ↑ The Agreement of the People, as presented to the Council of the Army, s. 2.

- ↑ The Agreement of the People, as presented to the Council of the Army, s. 3.

- ↑ The Agreement of the People, as presented to the Council of the Army, s. 4.

- ↑ House of Commons Journal Volume 5: 9 November 1647: Persons committed.

- ↑ Brailsford, p. 320.

- ↑ Brailsford, p. 321.

- ↑ Brailsford, p. 324.

- ↑ Brailsford, p. 317.

- ↑ Brailsford, p. 616.

- ↑ Calendar of Clarendon State Papers, volume 2, p. 236-7

- ↑ Haberdashers' register of Apprentices and Freemen 1526-1933.

- ↑ Haberdashers' register of Apprentices and Freemen 1526-1933.

- ↑ Calendar of State Papers Domestic Series 1651–1652, p. 578.

- ↑ Calendar of State Papers Domestic Series 1651–1652, p. 586.

- ↑ Gentles (1976)

- ↑ House of Commons Journal Volume 6: 16 July 1649: Crown Lands.

- ↑ Acts and Ordinances of the Interregnum, 1642-1660: July 1649: An Act for sale of the Honors, Manors, Lands heretofore belonging to the late King, Queen and Prince.

- ↑ Chidley (1652). Retsah, p. 2.

- ↑ Chidley (1652). Retsah, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Gentles, Ian J. "Pride, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22781. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Chidley (1652). Retsah, p. 14.

- ↑ Chidley (1652). Retsah, p. 13.

- ↑ Chidley (1652). Retsah, p. 15.

- ↑ Chidley (1652). Retsah, p. 16.

- ↑ Chidley (1652). Retsah, p. 17.

- ↑ Chidley (1652). Retsah, p. 19.

- ↑ Chidley (1652). All those wel-affected Creditors of the Commonwealth.

- 1 2 Chidley (1653), page unnumbered.

- ↑ Woodford, p. 9.

- ↑ Gaunt. Cromwellian Britain - Widecombe-in-the-Moor, Devon.

- ↑ House of Commons Journal Volume 7: 20 October 1656: Obnoxious Publication.

- ↑ Woodford, p. 8.

- ↑ House of Commons Journal Volume 7: 20 October 1656: Regulating the Press.

- ↑ House of Commons Journal Volume 7: 28 October 1656: A Person discharged.

- ↑ Chidley (1657), p. 1.

- ↑ Chidley (1657), p. 1-2.

- ↑ Chidley (1657), p. 2.

- ↑ Chidley (1657), p. 3-4.

- ↑ House of Lords Journal Volume 11: 1 May 1660: The King's Declaration.

- ↑ House of Commons Journal Volume 7: 9 May 1657: Privilege.

- ↑ Chidley (1652). Retsah, p. 1.

- ↑ Hearth Tax: City of London 1662, Bishopgate ward, Chequer Alley.

- ↑ Johns, p. 33.

References

- "74. The Agreement of the People, as presented to the Council of the Army". Constitution Society. 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Brailsford, Henry Noel (1961). Hill, Christopher (ed.). The Levellers and the English Revolution (1983 ed.). Nottingham: Spokesman. ISBN 0851241549.

- Brown, A. J. (1906). Crippen, T. G. (ed.). "Bury St. Edmund's Church Covenants". Transactions of the Congregational Historical Society. Congregational Historical Society. 2: 332–6. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Brown, David (1650). Two Conferences between some of those that are called Separatists & Independents. Ann Arbor and Oxford: Early English Books Online - Text Creation Partnership. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Brown, David (1652). The Naked Woman. Ann Arbor and Oxford: Early English Books Online - Text Creation Partnership. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Burrage, Champlin (1912). The Early English Dissenters in the Light of Recent Research (1550–1641). Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Burrage, Champlin, ed. (1912). The Early English Dissenters in the Light of Recent Research (1550–1641). Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Chidley, Katherine (1641). The Justification of the Independant Churches. Ann Arbor and Oxford: Early English Books Online - Text Creation Partnership. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Chidley, Samuel (1652). Retsah, a cry against a crying sinne. Ann Arbor and Oxford: Early English Books Online - Text Creation Partnership. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Chidley, Samuel (1652). All those wel-affected Creditors of the Commonwealth. Ann Arbor and Oxford: Early English Books Online - Text Creation Partnership. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Chidley, Samuel (1653). A Remonstrance to the Creditors of the Common-Wealth of England, Concerning The Publique Debts of the Nation. Ann Arbor and Oxford: Early English Books Online - Text Creation Partnership. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Chidley, Samuel (1657). To His Highness the Lord Protector, and the Parliament of England, &c. Ann Arbor and Oxford: Early English Books Online - Text Creation Partnership. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- "City Of London, Haberdashers, Apprentices and Freemen 1526-1933". Findmypast. 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- Clarke, Samuel (1651). A Generall Martyrologie … Whereunto are added, The Lives of Sundry Modern Divines. London: Underhill and Rothwell. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Coulton, Barbara (2010). Regime and Religion: Shrewsbury 1400-1700. Little Logaston: Logaston Press. ISBN 978-1-906663-47-6.

- Dunn Macray, W., ed. (1869). Calendar of the Clarendon State Papers Preserved in the Bodleian Library. Vol. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Edwards, Thomas (1646). Gangraena. London: Ralph Smith. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Firth, C. H.; Rait, R. S., eds. (1911). Acts and Ordinances of the Interregnum, 1649–1660. London: Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Fletcher, William George Dimock, ed. (1913). Shropshire Parish Registers: Diocese of Lichfield: St Chad's, Shrewsbury. Vol. 1. London: Shropshire Parish Register Society. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- H. E. Forrest (1924). "Shrewsbury Burgess Roll". Hathi Trust Digital Library. Shropshire Archaeological and Parish Register Society. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Peter Gaunt. "City Of London, Haberdashers, Apprentices and Freemen 1526-1933". Oliver Cromwell Website. Cromwell association. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- Gentles, Ian (1976). "The Purchasers of Northamptonshire Crown Lands 1649–1660 (Abstract)". Midland History. Maney. 3 (3): 206–32. doi:10.1179/mdh.1976.3.3.206.

- Gentles, Ian J. "Chidley, Katherine". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37278. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Gentles, Ian J. "Chidley, Samuel". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37279. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Gentles, Ian J. "Pride, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22781. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Gillespie, Katharine (2004). Domesticity and Dissent in the Seventeenth Century: English Women's Writing and the Public Sphere. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511189548.

- Green, Mary Anne Everett, ed. (1877). Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, 1651–1652. London: Longman. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- Johns, Adrian (2008). "Coleman Street" (PDF). Huntington Library Quarterly. Huntington Library. 71 (1): 33–54. doi:10.1525/hlq.2008.71.1.33.

- Journal of the House of Commons: Volume 5, 1646-1648. Institute of Historical Research. 1802. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Journal of the House of Commons: Volume 6, 1648-1651. Institute of Historical Research. 1802. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Journal of the House of Commons: Volume 7, 1651-1660. Institute of Historical Research. 1802. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- Journal of the House of Lords: Volume 11, 1660-1666. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- "London Hearth Tax: City of London, 1662". British History Online. Centre for Metropolitan History. 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Ritor, Andrew (1642). A treatise of the Vanity of Childish Baptism (PDF). London. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- Shaw, William A. (1900). A History of the English Church during the Civil Wars and under the Commonwealth, 1640–1660. Vol. 1. London: Longmans, Green. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Shaw, William A. (1900). A History of the English Church during the Civil Wars and under the Commonwealth, 1640–1660. Vol. 2. London: Longmans, Green. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Woodford, Benjamin (2014). "Developments and Debates in English Censorship during the Interregnum". Early Modern Literary Studies. Humanities Research Centre, Sheffield Hallam University. 17 (2). Retrieved 9 February 2016.