Samuel Henzi (19 April 1701 in Bümpliz of Bern – executed 17 July 1749 in Bern) was a Swiss writer, politician and revolutionary. He is chiefly known for his role in the "Henzi conspiracy" of June 1749, which aimed to overthrow the patrician government of Bern.

Life

Samuel Henzi was born the son of the pastor Johannes Henzi (1667-1740) and Maria Katharina Herzog. In his position as a copyist and bookkeeper at the Bern salt chamber, he was self-taught and possibly taught the patrician daughter Julie Bondeli as a private tutor. In the hope of a career and fortune, he bought himself a captain's position in the service of the Duke of Modena and Reggio, but failed miserably.[1]

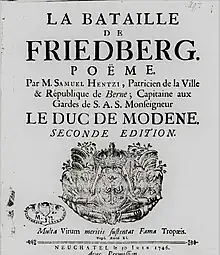

In 1744, Samuel Henzi, who had signed a memorial for the restoration of Bern's old constitution, was expelled by resolution of the country's Great Council. In Neuchâtel he was editor of the Mercure Suisse and a contributor to the Journal hélvetique. Henzi wrote several French poems, some under the pseudonym M.O.L.E.E.B.H. From 1747 he published the three-volume La messagerie de Pinde, which contains an ode and a sonnet on the election of the Bernese mayor Christoph Steiger. He wrote an ode to Frederick the Great and supported Johann Jakob Bodmer in his polemics against Johann Christoph Gottsched. In 1748 he was pardoned and worked in Bern as a sub-librarian. Johann Rudolf Sinner, who was only 18 years old at the time, was given preference when he applied to be senior librarian.

In 1749, together with his brother-in-law, the merchant Samuel Niklaus Wernier, he got involved in a conspiracy that aimed to overthrow the Bernese government and that was known as Burgerlärm, later known as the "Henzi conspiracy" (Henzi-Verschwörung). The group remained relatively small and divided. Henzi himself described himself on one of his book covers as Patricien de la Ville et République de Berne. The group was betrayed by the theology student Friedrich Ulrich (1720-1781) and Henzi was executed along with the two other participants, Samuel Niklaus Wernier and Emanuel Fueter, lieutenant of the city guard.

In 1762 his drama Grisler ou l'ambition punie about Albrecht Gessler (= Grisler) and Wilhelm Tell was published posthumously and anonymously. The directory for bankruptcy auction [Geltstagsrodel] listed among his remains 52 titles of books in German, French, Italian and Latin.

Family

The Henzi family, which had been based in Bern since the mid-16th century, produced numerous theologians. Samuel Henzi's godparents were the later mayor Christoph Steiger I], his uncle and town doctor Samuel Herzog (1673–1743) and Maria Magdalena Zeerleder.[2] His grandfather was the tanner Johannes Henzi (1637–1706), Kastlan zu Zweisimmen. In his first marriage he was married to Rosina Wernier (1709-1738), in his second marriage to Esther Fischer (1719-1738) and in his third marriage to Katharina Malacrida (1707-1751), daughter of Niklaus Malacrida (1658–1742), watchmaker and banker.[3] Katharina Malacrida was the cousin of Maria Magdalena Malacrida, married to Samuel Güldin (1664–1745), pastor in Stettlen and Bern. Güldin was removed from office in 1699 as a co-founder of the within-church pietistic reform movement, and expelled from the country in 1702.[4] Christoph Steiger I was also godfather to Güldin's third child.[5] Samuel Henzi's godmother Maria Magdalena Zeerleder[6] was in his first marriage with the pietistic vicar Johannes Müller (1668–1705) married, second marriage to Daniel Knopf (1666–1738), agent of the Bank of Malacrida. Like Malacrida, Daniel Knopf also belonged to the pietistic circles.[7]

Henzi had two sons from his first marriage, Rudolf Samuel Henzi (1731-1803), steward of the pages of the prince governor in The Hague, publisher and writer in Paris; the other lived in Noyon. Ludwig Niklaus Henzi (1748–?), lieutenant colonel in Hungary, survived as a child from his third marriage.

Reception

The conspiracy attracted a great deal of attention in the foreign press and was sometimes glorified.[8] Gotthold Ephraim Lessing made Samuel Henzi the subject of one of his unfinished dramas, dated 1749 and first published in 1753, entitled Samuel Henzi. Lessing has explained his concept as follows: I will tell you what my intention was with it: It was this: to depict the rebel as opposed to the patriot, and the oppressor as opposed to the true leader. Henzi is the patriot, Ducret the rebel, Steiger the true leader, and this or that councilor the oppressor. Henzi, as a man whose heart was as excellent as his spirit, is driven by nothing but the welfare of the state; no self-interest, no mere lust for change, no revenge inspires him; he seeks nothing but to expand freedom to its old limits again, and seeks to do so by the most lenient means, and when these should not work, by the most cautious force. Duecret is the complete opposite. Hatred and thirst for blood are his virtues, and foolhardiness is his entire merit.[9]

Johann Caspar Lavater, in his periodical Der Erinnerer in 1766, compared Samuel Henzi to Socrates, stating, Henzi found the robe of the magistrate present at his execution so comical that he had to laugh about it.' '[10] Due to criticism, Lavater withdrew the statement shortly after publication, pointing out that it was merely an unconfirmed anecdote.[11]

There is no known contemporary portrait of Henzi. The portrait of Samuel Henzi by Sigmund Barth, which is often shown in connection with Samuel Henzi, is a depiction of the Bernese wood turner Samuel Cornelius Henzi (1718–1777).[12] In 1942, Samuel Henzi was given a monument as a stucco relief on the ceiling of the lobby of the Bern Town Hall, placed in a gallery of historical personalities from Bern's history.

Samuel Henzi inspired the Bernese author Martin Bieri to write his literary work Henzi Sulgenbach. A Lessing implant.[13] The Sulgenbach is mentioned in the title because the conspirators met in 1749 at the Sulgenbach at Giessereiweg 22.[14]

Lore

The historian Johann Anton von Tillier (1792–1854) complained about the lack of documents on civil unrest in the archives of the Bernese government.[15] The archive inventory from 1826 names the Cabinet No. 3 of documents «Cahier because of the discovered conspiracy of 1749, 2 volumes. Also: Manual concerning the conspiration discovered in 1749.»[16] The historian and politician Bernhard Rudolf Fetscherin[17] noted the missing files in 1834, when the state archive was handed over by the state clerk Albrecht Friedrich May.

In 1837 the absence was confirmed to his successor Gottlieb Hünerwadel.[18] Fetscherin kept the tower book from 1749 for a long time,[19] which he returned in 1849 at the request of Ulrich Ochsenbein.[20] In 1892 Heinrich Türler stated that these files had been missing since 1837.

In July 2019, the State Archives Bern announced that the "Manual ansehend die im Julio 1749 in der Statt Bern entdekte Conspiration [...]" was returned to the inventories of the canton of Bern.[21]

References

- ↑ "Henzi, Samuel". hls-dhs-dss.ch (in German). Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ↑ Burger Taurodel 1689 -1711, VA BK 331, p. 397. in the Catalog of the Burgerbibliothek of Berne

- ↑ Jolanda Leuenberger-Binggeli: Nikolaus Malacrida in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ↑ Rudolf Dellsperger: Samuel Güldin in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ↑ Noth 2005, p. 65; the Burgerbibliothek Bern keeps a letter from Güldin to Christoph Steiger (I.), see Mss.h.h.XIII.102 (21).

- ↑ Daughter of Niklaus Zeerleder (1628–1691), provost in Bern, cantor, pastor in Kirchberg/BE, dean in Burgdorf and Katharina Dürrholz.

- ↑ Dellsperger 1984, p. 122.

- ↑ Anne-Marie Dubler: Henzi conspiracy in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ↑ Albert Meier (2008). "Gotthold Ephraim Lessing; Lessing as a Gottschedian; Samuel Henzi/The Young Scholar" (PDF). Literaturwissenschaft-online. lecture summer semester. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-05. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- ↑ Baum 2012 II, p. 861.

- ↑ Baum 2012 II, p. 861.

- ↑ See Wikimedia Commons

- ↑ "Martin Bieri – Henzi Sulgenbach". abendschein.ch. Retrieved 2020-02-26.

- ↑ Berchtold Weber. "Giessereiweg". Historisch-Topografies Lexikon der Stadt Bern, Bern, 2016. Retrieved 2020-02-26.

- ↑ Henzi 1951, p. 41.

- ↑ Henzi 1951, p. 41.

- ↑ Fetscherin's son Rudolf Friedrich Fetscherin was married to Eugenie Louise Fueter (1833 –1900), great-great-granddaughter of the “conspirator” Gabriel Fueter (1714–1785).

- ↑ Henzi 1951, p. 41.

- ↑ Tower book, volume 1749, B IX 493 in the Catalog of the State Archives Bern.

- ↑ Henzi 1951, p. 41.

- ↑ https://www.be.ch/start/starten/medien/medienmitteilungen.html?newsid=4BC8313E-34CA-B5DA-09F97B560138