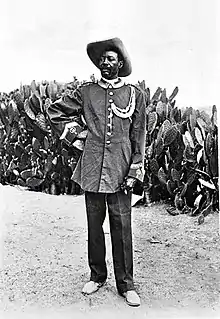

Samuel Maharero (1856 – 14 March 1923) was a Paramount Chief of the Herero people in German South West Africa (today Namibia) during their revolts and in connection with the events surrounding the Herero genocide. Today he is considered a national hero in Namibia.

Life

Samuel Maharero was son to Maharero, an important Herero warrior and cattle raider. He was baptised in 1869[1] and went to the local Lutheran schools, where he was seen as a potential priest. When his father died in 1890, he gained the chieftainship in the area of Okahandja, although he did not gain much of his father's wealth and cattle according to Herero inheritance customs. Initially, he maintained fairly good relations with the German colonial administration under Theodor Leutwein. However, increasing problems, involving attacks by German farmers, economic difficulties and pests, and the use of Herero land for railroads, all lead to diminished relations. Angered by the ill-treatment of the Herero people by German settlers and colonial administrators, who viewed the tribes as a cheap source of labor for cotton and other export crops, Maharero secretly planned a revolt with the other chiefs against the German presence, though he was well aware of the odds against him. In a famous letter to Hendrik Witbooi, the Namaqua chief, Maharero sought to build alliances with the other tribes, exclaiming "Let us die fighting!"[2]

War against Germany

The initial attacks in the revolt, begun on January 12, 1904, were successful and involved the killings of 123 persons, mostly German landowners (Marero had issued an order to his forces to avoid harming Boers, English, missionaries, and other non-German whites).[3] By January 14, mounted Herero raiders had reached Omarasa, and the Waldau and Waterberg post offices were destroyed. The Waterberg military station was occupied by Herero and all soldiers under the command of Unteroffizier Gustav Rademacher were killed. Maharero allowed missionaries with a small number of German women and children free passage to Okahandja. They reached their destination on April 9, 1904. On January 16, Gobabis was besieged and a German military company was ambushed and destroyed near Otjiwarongo. After this loss, Leutwein was replaced as military leader by Lothar von Trotha, who brought 15,000 troops and created a bounty of 5,000 marks for the capture of Maharero. Herero forces were defeated by colonial forces using breech-loading artillery and 14 Maxim belt-fed machine guns at the Battle of Waterberg on August 11, 1904, and the remaining Hereros (including women, children, and the elderly) were driven into the deserts of the Omaheke Region. Tens of thousands of the Herero died of thirst, starvation, or disease. Those who attempted surrender were shot. After the extermination order was countermanded by Berlin, captured survivors were sent to a concentration camp at Shark Island.

Maharero succeeded in leading around 1000 of his people to the British Bechuanaland Protectorate (today Botswana). He remained leader of the exiled Herero, and became an important vassal of Sekgathôlê a Letsholathêbê, a chief in northern Bechuanaland.

Samuel Maharero died there in March 1923, and his body was temporarily buried in Bechuanaland.[4] On August 23, 1923, his body was returned to Okahandja and was ceremoniously reburied alongside his ancestors, an occasion that the Herero people still celebrate on Herero Day.

Recognition

Samuel Maharero is one of nine national heroes of Namibia that were identified at the inauguration of the country's Heroes' Acre near Windhoek. Founding president Sam Nujoma remarked in his inauguration speech on 26 August 2002 that:

Chief Samuel Maharero [...] started to make plans for an uprising against the German colonial authorities and white German settlers in the country. As a result, in January 1904 the uprising began and chief Maharero's forces surrounded the German colonial settlers at Okahandja, Omaruru, and the famous Battle of Ohamakari near the Waterberg Mountain. The strength of his forces compelled the German colonial troops to send in reinforcements under the notorious General Lotha von Trotha who carried out an extermination order to wipe out all women, children and elderly persons. [...] To his revolutionary spirit and his visionary memory we humbly offer our honor and respect.[5]

Maharero is honoured in form of a granite tombstone with his name engraved and his portrait plastered onto the slab.[5]

References

Notes

- ↑ Nils Ole Oermann (1999). Mission, Church and state relations in South West Africa under German rule (1884-1915). F. Steiner. ISBN 351507578X. OCLC 611198756.

- ↑ Gewald, Jan-Bart, Herero Heroes: A Socio-political History of the Herero of Namibia, 1890-1923, London: James Curry Ltd (1999), ISBN 0852557493, p. 156

- ↑ Chalk, Frank Robert (1990). The history and sociology of genocide : analyses and case studies. Jonassohn, Kurt., Montreal Institute for Genocide Studies. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300044461. OCLC 20422757.

- ↑ Silvester, Jeremy, ed. (13 July 2015). Re-viewing resistance in Namibian history. African Books Collective. ISBN 9789991642284. OCLC 961903227.

- 1 2 Nujoma, Sam (26 August 2002). "Heroes' Acre Namibia Opening Ceremony - inaugural speech". via namibia-1on1.com.

Literature

- Harring, Sidney. "Herero." Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity. Ed. Dinah Shelton. Vol. 1. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005. 436–438. 3 vols. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Thomson Gale.

External links

![]() Media related to Samuel Maharero at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Samuel Maharero at Wikimedia Commons