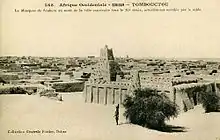

| Sankore Madrasa | |

|---|---|

Médersa de Sankoré | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Location | |

| Location | Timbuktu, Mali |

Shown within Mali | |

| Geographic coordinates | 16°46′33″N 3°00′20″W / 16.7758876°N 3.0056351°W |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Mosque / University |

| Style | Sudano-Sahelian architecture |

| Funded by | Mansa Musa |

Sankoré Madrasa (also called the University of Sankoré, or Sankore Masjid, French: Université de Sankoré) is one of three ancient centers of learning located in Timbuktu, Mali. It is believed to have been established by Mansa Musa,[1] who was the ruler of the Mali Empire, though the Sankoré mosque itself was founded by an unknown Malinke patron. The three mosques of Sankoré: Sankoré, Djinguereber, and Sidi Yahya comprise the University of Timbuktu. The madrasa went through multiple periods of patronage and renovation under both the Mali Empire and the Songhai Empire until the Battle of Tondibi in 1591 led to its looting. Madrasa (مدرسة) means school/university in Arabic and also in other languages that have been influenced by Islam.

History

The University of Sankoré has its roots in the Sankoré Mosque, which was built in 988 AD with the financial backing of a Malinke woman.[2] It was later restored between 1578 and 1582 AD by Imam Al-Aqib ibn Mahmud ibn Umar, the Chief Qadi of Timbuktu. Imam al-Aqib demolished the sanctuary and had it rebuilt with the dimensions of the Kaaba in Mecca. The Sankoré University prospered and became a very significant point of learning in the Muslim world, especially under the reign of Mansa Musa (1307–1332) and the Askia dynasty (1493–1591).[3]

Growth as a center of learning

.svg.png.webp)

Timbuktu had long been a destination for merchants from the Middle East and North Africa. It was not long before ideas as well as merchandise began passing through the fabled city. Since most, if not all, of these traders were Muslim, the mosque would see visitors constantly. The temple accumulated a wealth of books from throughout the Muslim world becoming not only a center of worship but a center of learning. The reputation of Timbuktu brought greater audiences in and bolstered the population of the madrasa. Books became more valuable than any other commodity in the city, and private libraries sprouted up in the homes of local scholars. The manuscripts and books found in Sankoré Madrasa spoke to its relationship with other Islamic centers of learning, with its importance to Timbuktu being realized with the existence of a whole class that lived at the mosque of Sankoré and were held in high regard by the people and foreign signatories. Even the Songhai Kings’ would bestow numerous gifts upon them during Ramadan.[4]

Apex and Fall

By the end of Mansa Musa's reign (early 14th century CE), the Sankoré Masjid had been converted into a fully staffed madrasa (Islamic school, or in this case, university) with the largest collections of books in Africa since the Library of Alexandria. With the rise of the Songhai Empire under Askia Muhammad, the empire ushered in the golden age of the Sankoré madrasa, drawing in scholars from as far as Cairo and Syria. The madrasa at one point enrolled more foreign students than New York University did in 2008.[4] The level of learning at Timbuktu's Sankoré University was superior to that of many other Islamic centers in the world. Scholars from Sankoré would engage in learning or teaching while completing the Hajj. The trade in books within the Islamic world was one of the most important aspects of the university where thousands upon thousands of manuscripts were written.[5] The Sankoré Masjid was capable of housing 25,000 students and had one of the largest libraries in the world, housing between 400,000 and 700,000 manuscripts. In 1591 AD, an invasion by[4] Ahmad al-Mansur of Morocco plundered Songhai for its wealth after the Battle of Tondibi, including the Sankoré Madrasa, starting a long decline of the West African states.[6] A few days after the death of Askia Daoud, the last monarch of the Songhai Empire, IImam al-Aqib, the restorer of the mosque and chief Qadi of Timbuktu, died of natural causes.[7]

Modern Day

The integrity of the Sankoré Madrasa has been at risk with increased urbanization and contemporary construction in Timbuktu. Irreversible damage has been done to the mosque due to the erection of the Ahmad Baba Center, as well as flooding and a lack of restoration work. As a result, the integrity of the traditional building techniques are at risk. However, there are currently several restoration and protective committees being funded by the government to prevent further damage. The Management and Conservation Committee of the Old Town, in coordination with the World Heritage Center, held long term plans to create a 500 foot buffer zone to protect the madrasa and create a sustainable urban development framework.

Organization

The University of Sankoré managed to effectively house over 25,000 students, which was a fourth of the entire Timbuktu population at the time, in its 180 facilities.[1]

Academic Administration

As the center of an Islamic scholarly community, the university was very different in organization from medieval universities, where students studied in one institution and were awarded degrees by the college. In contrast, the early Sankoré university had no central administration, student registers, or prescribed course of study. The school was divided into several individual madrasas, each run by an imam or ulema, a single headmaster that had a role similar to that of a dean. As such, it is one of the earliest examples of a system reminiscent of the modern residential college system. Most students learned from a single teacher throughout their entire 10-year education, having a relationship akin to that of an apprenticeship, but some were given the option to study at multiple madrasas under a series of teachers. Classes were held either at the mosque or at the teacher's home. While most madrasas were funded by benefactors through endowments in the Muslim tradition of waqf (charitable giving), the students at the Sankoré Madrasa had to finance their own tuition with money or bartered goods.[2]

Architecture

The courtyard was constructed to exactly match the dimensions of the Kaaba in Mecca, one of Islam's most holy sites.[2] Classes took place in the open courtyards of the mosque-like structure, made entirely of clay and stone beams. The university still stands intact today, likely due to Al-Sahili's directive to incorporate a wooden framework into the mud walls in order to facilitate repairs after the rainy season.[8] As worship was not its main focus, the Sankoré University was smaller and less intricate than earlier Malian mosques such as the Great Mosque of Djenné.[9]

Curriculum

Islamic schooling had existed in West Africa since the 11th century, and although it was initially intended for elites, the Qur’anic emphasis on equality in education allowed for the spread of the institution and increased literacy rates.[10] The Qur'an itself and the hadiths[10] stress the search for knowledge, and Islamic scholarship, especially in the Golden Age of Islam, focused heavily on education.[11] Al-Kābarī, a scholar that descended from Timbuktu, Mali, and a professor at the Sankoré Madrasa helped create the curriculum, focusing on religious teachings.[12] The Songhai Empire developed Mali as a center for trade and used the growing economic power to further Islamic learning. Timbuktu itself housed 150 Qur'anic schools and became a major educational center in the Muslim world, producing influential jurists, historians, doctors, and theologians.[13] There existed no thorough curriculum for Islamic and Qur’anic studies in the Muslim world until schools like Sankoré Madrasa standardized a method of education.[14]

With the Qur'an being the foundation of all teachings, arguments that could not be backed by the Qur'an were inadmissible in discussions and debates. Madrasas differed in curriculum from traditional Qur’anic schools in that they focused primarily on Arabic grammar to understand holy texts and Islamic scholarship.[15] However, Sankoré Madrasa later expanded to teaching geometry, astronomy, mathematics, and history, drawing from its diverse library containing hundreds of thousands of manuscripts. At the height of Islamic education around the 16th century, Sankoré Madrasa educated between 15,000 and 25,000 students[10] in 180 schools, as well as became a center for the crafting and trading of manuscripts.[16] Between the 14th and 16th centuries, Sankoré Madrasa enrolled large numbers of students and continued to expand its curriculum and influence. The curriculum of Sankoré and other masjids in the area had four levels of schooling or "degrees". When graduating from each level, students would receive a turban symbolizing their level.

Degree of Studies

The first or primary degree (Qur'anic school) required a mastery of Arabic and certain African languages and writing along with complete memorization of the Qur'an. Students were also introduced to basic sciences at this level.

The secondary degree (general studies) degree focused on full immersion in the basic sciences. Students learned grammar, mathematics, geography, history, physics, astronomy, chemistry alongside more advanced learning of the Qur'an. At this level, they learned the hadiths, jurisprudence, and the sciences of spiritual purification according to Islam. Finally, they began an introduction to trade school and business ethics. On graduation day, students were given turbans symbolizing divine light, wisdom, knowledge and excellent moral conduct. After receiving their diplomas, the students would gather outside the examination building or the main campus library and throw their turbans high into the air and cheering.

The superior degree required students to study under specialized professors and to complete research work. Much of the learning centered on debates to philosophic or religious questions. Before graduating from this level, students attached themselves to a Sheik (Islamic teacher) and had to demonstrate a strong character.

Senior Roles

The last level of learning at Sankoré or any masjid was the level of judge or professor. These men worked mainly as judges for the city and throughout the region, dispersing learned men to all the principal cities in Mali. A third level student who had impressed his Sheik enough was admitted into a "circle of knowledge" and valued as a truly learned individual and expert in his field. The members of this scholar's club similar to the modern concept of tenured professors. Those who did not leave Timbuktu remained to teach or counsel the leading people of the region on important legal and religious matters. The scholars would receive questions from the region's kings or governors, and distribute them to the third level students as research assignments. After discussing the findings among themselves, the scholars would issue a fatwa on the best way to deal with the problem at hand.

Scholars of Sankoré

The African civilizations had a rich history in literature and the arts, long before their contact with the Arabian and Western worlds. The scholars employed at the Sankoré university were of the highest quality, "astounding even the most learned men of Islam".[17] As such, many scholars were later inducted as professors at universities in Morocco and Egypt.[4] Scholars were accomplished in multiple disciplines and employed to not only teach the students at the university, but to spread the madrasa's influence to other parts of the Islamic world.[18][9] Under the direction of Askia Daoud, ruler of the Songhai empire from 1549 to 1583, the university grew to encompass 180 facilities and house 25,000 students. Each facility was led by one Ulema, for a total of 180 scholars.

Notable Scholars

Some significant scholars include Abu Abdallah, Ag Mohammed ibn Utman, Ag Mohammed Ibn Al-Mukhtar An-Nawahi.[1] Most came from wealthy and religious families that were members of the Sufi Qadiriyya. The most influential scholar was Ahmad Bamba who served as the final chancellor of Sankoré Madrasa. His life is a brilliant example of the range and depth of West African intellectual activity before colonialism. He was the author of over forty books, with nearly each one constituting of a different theme. He was also one of the first citizens to protest the Moroccan conquest of Timbuktu in 1591. Eventually, he, along with his peer scholars, was imprisoned and exiled to Morocco. This led to the loss of his personal collection of 1600 books, which was one of the richest libraries of his day.[4]

Religious Pilgrimage

Apart from their time working in their theoretical studies and the preservation of knowledge, the scholars of Timbuktu were extremely pious. Many embarked on the Hajj, the religious pilgrimage to Mecca, and used this opportunity to hold discussions with scholars from other parts of the Muslim world. On the way home, the scholars showed their humble nature by both learning from other leading scholars in Cairo, and volunteering to teach pupils of other schools in Kano, Katsina, and Walata.[4] Mohammed Bagayogo received an honorary doctorate in Cairo on his holy pilgrimage to Mecca.[7]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "The University of Sankore, Timbuktu". Muslim Heritage. 2003-06-07. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- 1 2 3 "The University of Sankore Is Founded in Timbuktu." In Africa, edited by Jennifer Stock, 95-98. Vol. 1 of Global Events: Milestone Events Throughout History. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2014.

- ↑ Woods, Michael (2009). Seven wonders of ancient Africa. Mary B. Woods. London: Lerner. ISBN 978-0-7613-4320-2. OCLC 645691064.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Henrik Clarke, John. “The University of Sankore at Timbuctoo: A Neglected Achievement in Black Intellectual History.” The Western journal of black studies 1.2 (1977): 142–. Print.

- ↑ Hunwick, John (1999). Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire. Al-Sa'dī's Ta'rīkh al-sūdān down to 1613 and other Contemporary Documents. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

- ↑ Kobo, Ousman Murzik. “Paths to Progress: Madrasa Education and Sub-Saharan Muslims’ Pursuit of Socioeconomic Development.” In The State of Social Progress of Islamic Societies, 159–177. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016.

- 1 2 Michael A. Gomez. African Dominion : A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018, pg. 357.

- ↑ Hunwick, John (2003). "Timbuktu: A Refuge of Scholarly and RIghteous Folk". Sudanic Africa. 14 – via JSTOR.

- 1 2 "Wonders of the African World - Episodes - Road to Timbuktu - Wonders". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- 1 2 3 Hima, Halimatou (2020). "'Francophone' Education Intersectionalities: Gender, Language, and Religion". The Palgrave Handbook of African Education and Indigenous Knowledge. pp. 463–525.

- ↑ Thomas-Emeagwali, Gloria (January 1, 1988). "Reflections on the Development of Science in the Islamic World - and its diffusion into Nigeria Before 1903". Journal of the Pakistan Historical Societyb. 36: 41.

- ↑ Wright, Zachary V. (2020), "The Islamic Intellectual Tradition of Sudanic Africa, with Analysis of a Fifteenth-Century Timbuktu Manuscript", The Palgrave Handbook of Islam in Africa, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 55–76, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-45759-4_4, ISBN 978-3-030-45758-7, S2CID 226523945, retrieved 2021-12-05

- ↑ Olasupo Adeleye, Mikail (January 1, 1983). "Islam and Education". Islamic Quarterly. 27: 140.

- ↑ Abikan Abdulqadi, Ibrahim; Ahmad Folorunsho, Hussein (January 1, 2016). "THE STATUS OF SHARI'AH IN THE NIGERIAN LEGAL EDUCATION SYSTEM: AN APPRAISAL OF THE ROLE OF MADA'RIS". IIUM Law Journal. 24: 453.

- ↑ Kobo, Ousman Murzik (2016), "Paths to Progress: Madrasa Education and Sub-Saharan Muslims' Pursuit of Socioeconomic Development", The State of Social Progress of Islamic Societies, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 159–177, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-24774-8_7, ISBN 978-3-319-24772-4, retrieved 2021-12-05

- ↑ "Timbuktu". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2021-12-05.

- ↑ Dubois, Félix (1896). Timbuctoo the mysterious. New York, Longmans, Green and Co.

- ↑ Lawton, Bishop (2020-06-27). "Sankore Mosque and University (c. 1100- ) •". Retrieved 2021-11-30.

Further reading

- Saad, Elias N. (1983). Social History of Timbuktu: The Role of Muslim Scholars and Notables 1400–1900. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24603-2.

- Gomez, Michael A. (2018). African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691177427

External links

- Ancient Manuscripts from the Desert Libraries of Timbuktu, Library of Congress — exhibition of manuscripts from the Mamma Haidara Commemorative Library