| History of Indonesia |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

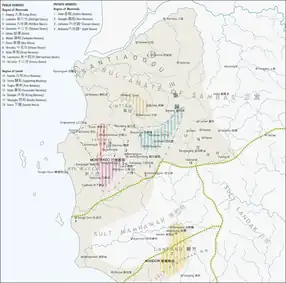

The Santiaogou Republic (Chinese: 三條溝公司, Hakka/Dutch: Sam-Thiao-Keoe; "Three gullies"), sometimes spelled as Santiago Republic in some sources, later renamed as the Sanda futing (Chinese: 三達副廳; "Deputy Hall of Three Reaches"), and lastly as the Hexian zhengting (Chinese: 和現正廳; "Legitimate Parliament of the Harmonies Present"), was a powerful Chinese kongsi federation formerly associated with Monterado (Chinese: 打勞鹿, Hakka: Montradok) district before moving to Sepang (Chinese: 昔邦, Hakka: Sapawang) in West Kalimantan, Borneo. It joined the Heshun Confederation in 1776, but left due to disputes and allied with the sultan of Sambas (and later the Dutch), succeeding in destroying its former ally Heshun and the Dagang kongsi. It was one of several miners' confederations in Borneo that later came into conflict with the Dutch to maintain their form of government, described as democratic.[1]

Despite its alliance with the Dutch, Santiaogou's kongsi was also dissolved and its lands officially handed over to the Dutch in 1854. The remaining Santiaogou miners moved northward into Sarawak, where they continued their mining operations until 1857.

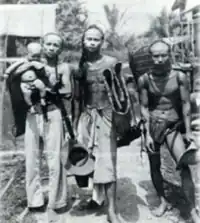

Demographics

Before the establishment of the Heshun Confederation, the Santiaogou Confederation had in its command approximately 800 members,[2] all of whom coming from the modern-day Huilai and Lufeng counties in Guangdong. Its members bore the surnames Wen 温 and Zhu 朱, though their membership diversified throughout the years.[3] Like the other thirteen founders of the Heshun Confederation, Santiaogou was a kaixiang kongsi 开香公司 (lit. "open incense kongsi"), or a kongsi who can trace its roots back to a temple cult organization in mainland China.

Its mining territory comprised originally in the settlements of Banyaoya (Chinese: 半要鴉, Hakka: Pandjawa), Baimangtou (Chinese: 白芒頭, Hakka: Phak-miong-theoe), Sibale (Chinese: 西哇黎, Hakka: Sibaler), and Serukan (Chinese: 凹下港, Hakka: Seroekam), all of which located east of the main town of Montrado. After its disassociation with the Heshun Confederation in the 1830s, Santiaogou's members fled to the more northern towns of Sepang, Seminis (Chinese: 西宜宜), and the port of Pamangkat (Chinese: 邦戛).[3] At its height following the disassociation, the Santiaogou controlled twelve major kongsi-mines with up to forty smaller cooperative mines.[4]

History

Early history

Little is known about Santiaogou's history prior to the formation of the Heshun Confederation in 1776. Its power, compared to the other kongsis, led to Santiaogou becoming an influential member of the Confederation. Santiaogou built an elaborate kongsi house in Montrado, the epicenter of Heshun activities, before 1820. East of Montrado, bordering the Lara region, the Santiaogou built a long stockade along the mountains, so large that it "resembled the Great Wall".[5]

In 1807,[2] the growing Dagang kongsi and Jielian kongsi squabbled over mining rights near the territories of the Shangwu in Montrado (a large fortified building in the south, used often as kongsi houses of the Dagang), the Santiaogou sided with the Dagang, and assisted Dagang in kicking out the Jielian and forcing its members to Pahang (Chinese: 巴亨).[6] In 1808, another quarrel surfaced with Dagang and Xin Bafen, to which the Santiaogou again helped aid the former; Zhu Fenghua, an able commander from Santiaogou, was put in charge of the Dagang and Santiaogou troops. After the conflict, writers at the time recorded that Santiaogou was not given any spoils from Xin Bafen's destruction. Contemporary Sinologists speculate this was probably done to reduce Santiaogou's greatness, as later he would become a bitter enemy of the Dagang. At the end of the conflict, only seven kongsis of Heshun remained, while Dagang and Santiaogou possessed the real power.[5]

Rising Tensions with Dagang

Santiaogou's power steadily increased in the decade that followed, and finally peaked in winning the presidency after the 4th Heshun headman, Dagang-affiliated Liu Zhengbao, abdicated to visit his family in 1818. The Santiaogou affiliated headman, Hu Yalu, has his presidency end in disaster after he attempted to unite the Dagang and Santiaogou, two kongsis wildly differing in their occupations (Dagang was mainly artisan based in the rich bazaars of Montrado, while Santiaogou was rather agricultural), leading him to resign only after three months.[2]

Zhu Fenghua succeeded Hu Yalu's premature reign, probably the main candidate chosen by the Santiaogou in order to save face. After his service in the conflict with Xin Bafen, Fenghua was elected to the highly respected title of the Heshun's secretary (xiansheng). This, along with being the caretaker and foreign representative of the Heshun to the Sambas sultan and the later Dutch diplomats, made him an extremely powerful and affluent man. However, his relations and position in the Confederation made Fenghua want more than a temporary presidency and more than a figurehead that depended on the vote of the Heshun parliament. Fenghua attempted to nominate himself as headman-for-life in the Confederation, an unprecedented action that was considered blatantly disrespectful and almost the entire alliance turned against him. He was forced to concede,[7] and later flee to Sambas in 1820 where he enjoyed the protection of the Sambas sultan.

The opposition to Santiaogou, now headed by Dagang, prepared for conflict with Santiaogou, as they believed their leadership was incompetent. A letter was sent to Liu Zhengbao to request his return to Borneo, and the leaderless Santiaogou could not prevent Zhengbao's ascension to the presidency.[7] Santiaogou has been thoroughly weakened with the absence of its leader; Dagang was now the clear face of the alliance and had to request Dagang's protection for its assets that were now in jeopardy. As Santiaogou's beleaguered residents settled down for peace, an infuriated Zhu Fenghua, now friends with the Sambas sultan, would pursue a conflict.[5]

Dagang-Santiaogou Conflict

At this time, Heshun's mining activities had spread beyond Montrado and now had settlements eastward to Larah, northeast to Seminis, Sepang, Lumar, and northward to Pamangkat. Despite Santiaogou's reduced position, both it and Dagang claimed rights to mine in the region between Sepang and Seminis. It is in this status quo that Zhu Fenghua convinced the Sambas sultan and a contingent of Dutch forces that Dagang was conspiring to attack "Santiaogou"'s mines in Lara, and promised his family riches if they succeeded in helping him kick out the Dagang. This casus belli was false, as Larah, which was formerly Xin Bafen's territory, had been under Dagangs' control after Xin Bafen's destruction, and not Santiaogou's. In May 1822, spearheaded by a Santiaogou flank, a Dutch vanguard under Lieutenant von Kielbeg marched inland to Larah to stop the "Dagang invasion". After arriving in Larah, von Kielbeg died in action, and the rest of the Dutch soldiers were spared by the Dagang and sent back to Seminis.[7]

Santiaogou's Escape

Thoroughly embarrassed and dismayed by the expedition's results, Santiaogou's members decided to leave Montrado and move to an ally's stronghold. On June 23, 1822, Santiaogou quietly commanded its members living in its settlements to pack up and flee to the Gunung Penaring mountains, where the Xiawu kongsi is located. Xiawu was one of the few Larah kongsis that did not pledge allegiance to the Dagang, having such a strong connection with Santiaogou they were referred to as the "Little Santiaogou" kongsi. After arriving in Xiawu, Santiaogou chased away the Dagang-allied kongsis like Manhe, Yuanhe, and Shenghe. Dagang convened its remaining four members to raise a large army to stop this. After a few fruitless days of attempting to scale the Gunung Penarings, they finally made it over and marched into Larah, where Santiaogou's strongholds were destroyed. Santiaogou had to leave Xiawu to the northwest where they were able to be closer to the capital of Sambas.[5]

Dutch intervention

J.H. Tobias, the Dutch magistrate that was put in charge of West Borneo, mediated tensions between Dagang and Santiaogou, and called a meeting in Montrad on September 13, 1822. Here, Dagang and Santiaogou accused each other of beginning the conflict; Santiaogou particularly made what Tobias noted as "utterly idiotic" statements against the Dagang, saying that Dagang had destroyed their property when they could have protected their assets. After Tobias heard from the sultan of Sambas about the promises Fenghua made him and his family, he decided that it was indeed Dagang that was wrong. He decided to not fully accuse the Sambas sultan and the Santiaogou kongsi because he wanted to preserve peace and respect, although he favored the sultan and Santiaogou for unknown reasons.[5]

In January 1823, despite hearing Dagang retrieving its forces from Lara, Tobias suddenly formed an expedition to Lara, headed by Santiaogou soldiers and led by General de Stuers. The expedition failed to surprise the Dagang but won a very pyrrhic victory after taking a Dagang stronghold. After Tobias again approved an expedition to Montrado, resulting in the Dutch occupation of Montrado, Santiaogou's seal was present in the Dutch demands, ones that included "dissolving" the Heshun kongsi and strengthening Dutch authority in Montrado.[5]

When Tobias was replaced by M. van Grave, his provocative demands on the Dagang for poll taxes and hypothetical unification of all kongsi into a governmental district led Dagang to retaliate through burning Dutch and Santiaogou strongholds in 1824. Zhu Fenghua, who owned several lucrative coffee plantations at the time, attempted to defend the Dutch and his men, with no success.[5] Eventually, the military actions decreased and the Santiaogou settled with Sepang (a rich mining district once leased to Dagang) while Dagang settled with Lara. In return for their profits in Sepang, Santiaogou was forced to pay 10 taëls of gold every year to the Dutch.[5][8]

Battle of Pamangkat

After approximately two decades of relative Dutch isolation from West Bornean affairs, F. J. Willer was appointed as the new Dutch magistrate and took on a much more direct and provocative stance in dealing with the Heshun Confederation. Months of tension, including a Dutch blockade of the port of Sedau, led to a couple of incidents. First, a series of Dayak massacres on the frontier Chinese towns of Budok and Lumar led Dagang to suspect it was Santiaogou's doing, when it was actually the paranoid Sambas sultan who thought the Dagang would invade the capital. Dagang retaliated, but instead of invading Sambas, the army began targeting specifically Santiaogou aligned towns. In July 1850, a thousand Dagang soldiers laid siege to Sepang and defeated it after 12 days. Seminis fell soon after, followed by the towns of Sebawi (Chinese: 沙泊) and Shabo (Chinese: 沙啵). Pamangkat took the longest: it is believed its siege must have taken a few weeks, but Dagang at last conquered the city in August, leaving the remaining Santiaogou population to flee to the opposite side of the Pamangkat River under Sarawak jurisdiction. After Dagang left and the Dutch reclaimed Pamangkat, Dagang once again ousted the Dutch soldiers in September and made plans to attack the Lanfang Republic at Mandor, who were allied with Santiaogou. In the ensuing peace talks in November 1850 with the Dutch and Dagang, Santiaogou was absent from the conference, its members scattered to the north into Sarawak.[5]

The Split of the two Santiaogous

In the immediate aftermath, the Dutch debated on what to do with the remnants of the Santiaogou, and eventually agreed they were to be induced back from Sarawak to rule Pamangkat, as a sort of check for the Dagang and Heshun, as well as regrowing the Pamangkat environs, which had been left untended despite fertile soil. In 1851, Willer persuaded Montrado to remove its claims to Santiaogou. After some time, members of Santiaogou quietly returned to reoccupy their former mines, and its leaders renamed the kongsi to the Sanda futing ("Three reaches deputy hall") to be, at least in name, on par with the Heshun zongting, whose power has been wrenched by the Dutch.[5]

Willer soon realized the conundrum; since the Battle of Pamangkat, the majority of Santiaogou miners were stationed in Sarawak, which meant Willer was essentially tending to an organization that had its headquarters in the Rajah Brooke's domain. Willer demanded the immediate renunciation of this Sarawak alliance and said their name change was proof of their subjugation to the Dutch. Willer said the word san in Sanda futing had to be removed, as this associated the Dutch kongsi with the Sarawaki kongsi. The Sanda envoy became so incensed he declared that if this were to ever happen, the remaining miners in Dutch territory will leave for Sarawak. Willer, in his last decrees, changed the name of the kongsi one more time to Hexian zhengting and attempted to rally so that Santiaogou members would return from Sarawak; many did not.[5]

Legacy

The majority of Santiaogou immigrants found a new place in the similarly Chinese mining villages of interior Borneo, particularly the county of Bau in Kuching province, Malaysia. The earliest migrants settled there during its reign under the Bruneian Empire, but a spike of immigration in the mid 19th century coincided with James Brookes' rise in Sarawak. Along with other Chinese immigrants, the miners joined the pre-existing Twelve Companies (十二公司), a partnership of twelve kongsi federations that resembled Santiaogou's government, and greatly boosted their power and their population to about 4,000.[5] Their autonomy threatened the British settlers and plantation owners, leading to the Twelve Companies, under Liu Shan Bang, to attempt a coup against Brooke's rajahnate, only to fail and be brutally defeated. Descendants of the original Santiaogou miners can be found throughout Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei.[5]

References

- ↑ "CHINESE DEMOCRACIES 作者:袁冰陵(Yuan bingling)". www.xiguan.org. Retrieved 2021-07-11.

- 1 2 3 Schaank, S.H. (1893). De Kongsis van Montrado. Batavia. p. 32. OCLC 246096928.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 Schaank, S.H. (1893). De Kongsis van Montrado. Batavia. p. 36. OCLC 246096928.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Kielstra (1889). Bijdragen tot Borneo's Westerafdeeling. p. 508.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Bingling, Yuan. "Chapter 2 THE GOLDEN AGE OF THE FEDERATIONS OF MONTRADO AND MANDOR". Library of the Western Belvedere.

- ↑ Leiden (1993). Conflict and Accommodation in Early Modern East Asia: Essays in Honour of Erik Zürcher. pp. 294–295.

- 1 2 3 Veth. Borneo's Wester-afdeeling, vol. II. p. 124.

- ↑ Veth (1854). Borneo's Wester-afdeeling, vol. II. p. 439.